Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – August 2024

Notes & Queries – August 2024

Calling My Children Home

At recording sessions in August 1977, the Country Gentlemen recorded their last album for the Rebel label before showing up at Sugar Hill Records. The album was a gospel collection, their second, and it featured Charlie Waller, Bill Yates, Doyle Lawson and James Bailey. The title of the album was Calling My Children Home.

When the Country Gentlemen recorded the album’s title track, they probably had no idea that it would have far-reaching appeal. Ralph Stanley recorded it for a 1988 album I’ll Answer the Call. In 1992, Emmylou Harris featured it on her Live at the Ryman CD; it was later recycled on at least a half dozen retrospective discs of her music. And, in 2016, a Trio collection (Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt and Emmylou Harris) included a 1986 previously unissued version of the song that was recorded for, but omitted from, the first Trio album.

Over the years, I’ve fielded questions from people about the origins of this song. The most unusual one came five or six years ago by way of Rebel Records, which was approached by a filmmaker from New Zealand who wanted to use the song in a movie. The original Country Gentlemen/Rebel release listed “Calling My Children Home” as being arranged by Doyle Lawson, Charlie Waller and Bill Yates. But, to me, the song had a much older feel.

I reached out to several sources, including the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro. Despite their massive collection of period hymnals from the 1920s to the present, their findings were inconclusive.

On a whim, I recently decided to revisit the song. It didn’t take long, this time, to come across a syndicated newspaper article from 1952. A piece by Cliff Bonner was titled “Precious Memories – A Wandering Texan Recalls Scenes of Childhood”; it mainly dealt with hymn composer J. B. F. Wright’s popular 1923 hymn “Precious Memories.” Nearly 30 years later, Bonner described Wright as being “past three score and ten now, and crippled.” Bonner continued that “Wright recently returned to the scenes of his childhood and wrote ‘They Have Gone Away’ and ‘Calling My Children Home.’”

Now, with an author’s name in hand, I located an album on eBay by a group from Elizabethton, Tennessee, called the Hardin Brothers Quartet. A photo of the back of the album cover revealed the song “Calling My Children Home” with the writer’s name listed as J. B. F. Wright. I ordered the album and promptly compared it to the Country Gentlemen release: it was the same song!

John Braselton Fillmore Wright was born in Rutledge, Tennessee, on February 21, 1877. At the age of two, he moved with his family to Groesbeck, Texas. Music was an important part of family life. In the Bonner article, Wright recalled his mother as being one of the “sweetest singers of her generation” and among his earliest memories were his mother and father singing together at home.

While Wright had no extensive training in music, he did attend one eighteen-day school that taught the rudiments of shape note singing. He was reported to have written anywhere from 200 to 500 hymns. However, the hymnary.org website, which contains the first lines to over a million collected hymns from a database of 6,675 hymnals, counts only 20 titles that are attributed to Wright.

Discrepancies notwithstanding, Wright was very active in gospel singing. His hometown newspaper, The Hamlin Herald, cited several examples. One, from a June 29, 1923, edition, noted that “the singing at J. B. F. Wright’s Saturday night was well attended, most all said they had a nice time.” The Big Spring Daily Herald from May 4, 1944, reported that Wright would be in attendance at the West Texas Singing Convention that was to be held in the town of Snyder.

Throughout his adult life, Wright worked as a farm laborer and later as a nurseryman. Songwriting was always an avocation. Despite the popularity of his most popular hymn, “Precious Memories,” he actually derived very little in the way of monetary compensation. His process, however, never appeared to be profit-driven. A quote by Wright on the hymnary.org website described how he wrote “by inspiration, only when the mood comes on the words and melody flow from my soul like the water from a babbling brook.” He continued, “Without this inspiration I could not write . . . all my songs came through life’s severest tests.” Such was apparently the case with “Calling My Children Home.”

The Hardin Brothers Quartet were, perhaps, the earliest known group to have recorded the song. As their name implies, the group was composed of brothers—four of them: Gilbert, Wesley, Auda and Hobart Hardin. They first began singing together in 1930 but didn’t gain much regional recognition until they started performing live on radio in the early 1940s. By their own estimation, the brothers performed at nearly every church in Carter County, Tennessee, and sang at hundreds of funerals and church homecomings. (One year, they sang at over 200 hundred funerals, including two separate occasions where there were four such singings in one day!) They were mainstays at the annual Tri-State Singing Convention in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, which started in 1921.

The Hardin Brothers sang from shaped-note hymnals. Although they performed acappella, some of their album recordings included guitar, bass and electric guitar. The group never charged for their services and minimized expenses by traveling together in one car. In addition to performances in their native Tennessee, they also traveled to West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, and North and South Carolina.

In 1950, the group released two 78 rpm discs on the Rich-R-Tone label. The four songs included “Stormy Waters,” “I Will Lay My Burdens Down,” “O Jerusalem Fair,” and “I’ll Leave My Troubles Here Below.” A decade later, they released several 45 rpm singles and EPs. It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that the group realized their biggest recorded output. Their second long-play album was called I’ll Wear a White Robe. They characterized the title song as being, perhaps, the most requested one of their careers. “Calling My Children Home” appeared on the album.

In a June 2000 Bluegrass Unlimited article about Doyle Lawson, author Les McIntyre wrote that “having grown up in East Tennessee near Kingsport, Doyle was exposed to many local gospel groups like the Highland Harmoneers, the Hardin Brothers, and the Duck Creek Quartet.” Indeed, in the notes to Doyle’s 2005 album There’s a Light Guiding Me, he wrote of one of the songs on the disc: “I believe I first heard the Hardin Brothers Quartet sing this one quite a few years ago.” Given Doyle’s proximity to the Hardin Brothers’ home turf of Elizabethton, Tennessee, a scant 30 miles away, and his familiarity with the group, it’s a fairly safe bet that the Hardin Brothers provided the inspiration for the Country Gentlemen’s recording of “Calling My Children Home.”

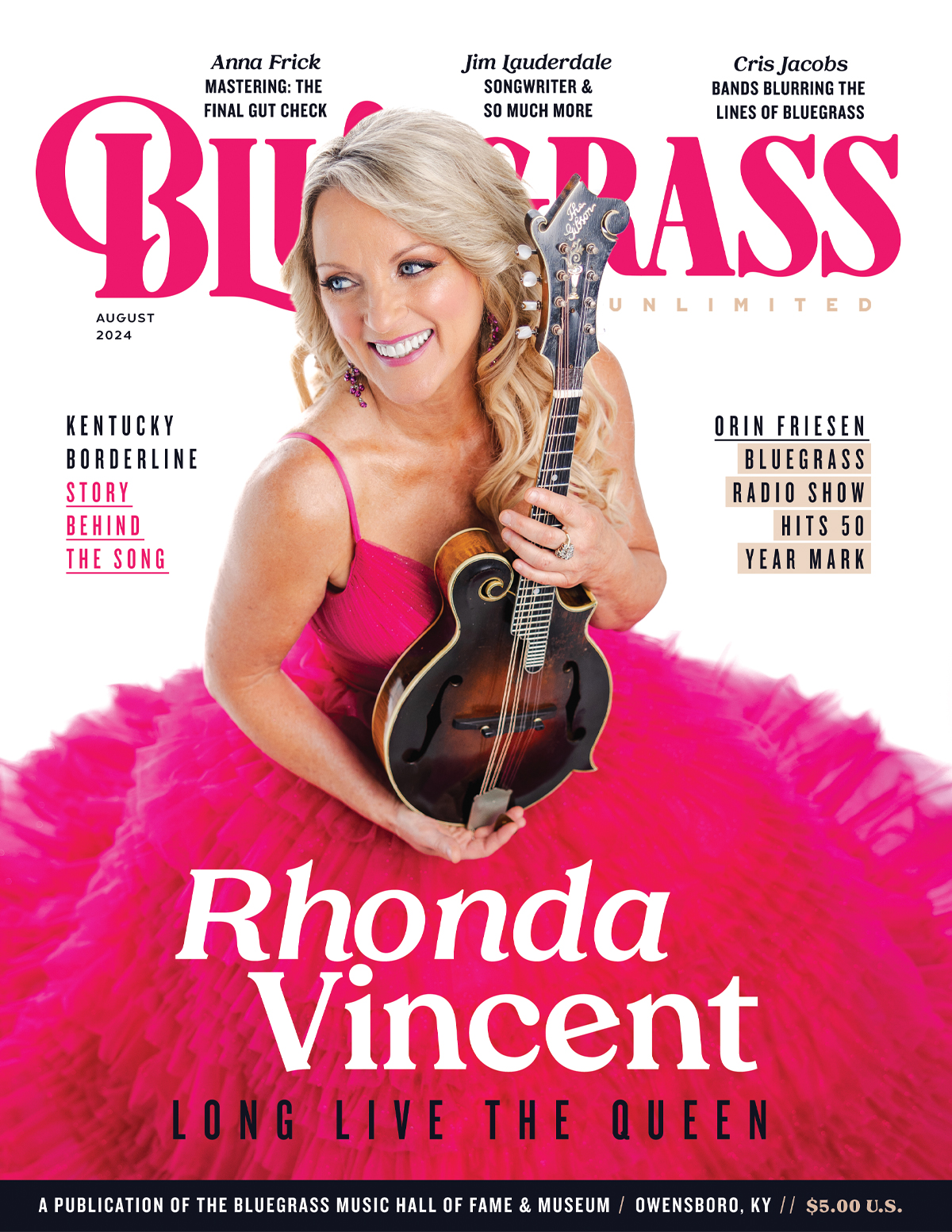

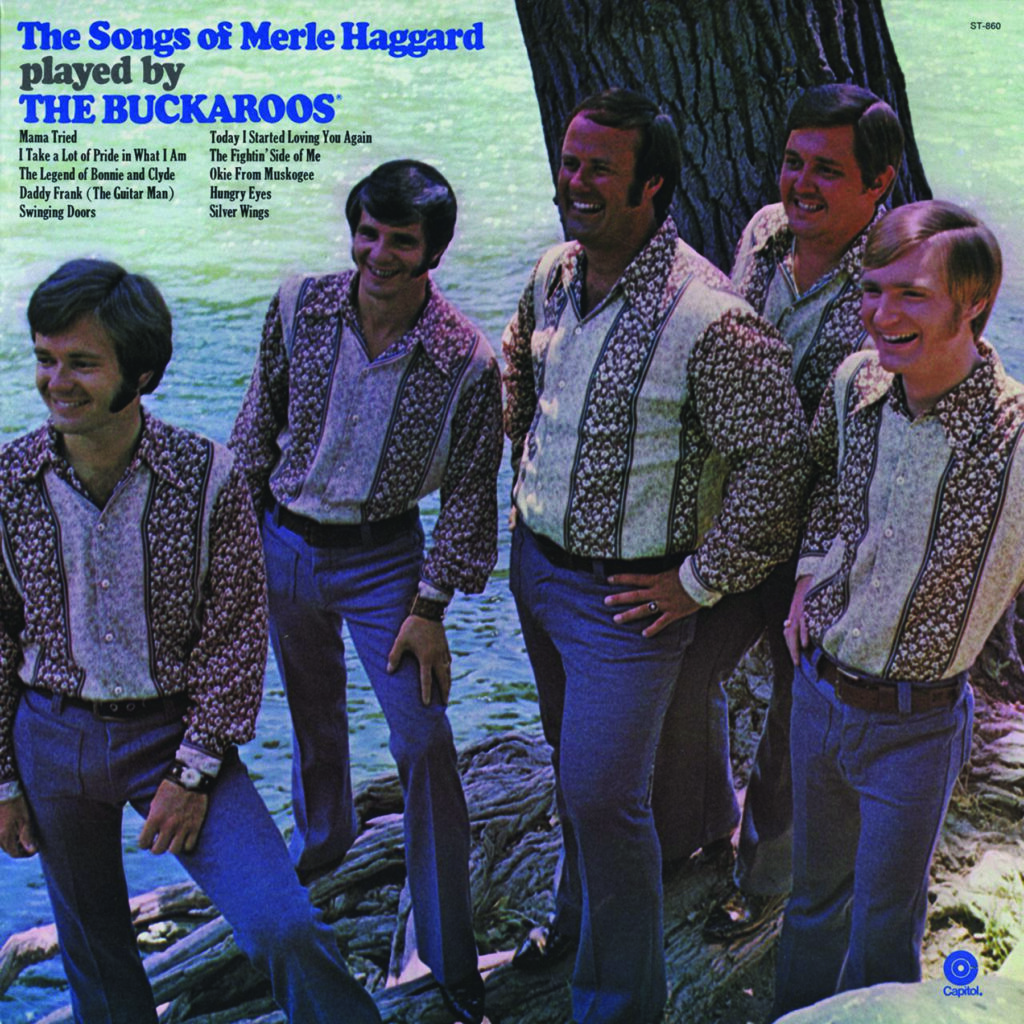

Ronnie Jackson, Banjo Man

Reader Wayne Hoffman asked recently about Ronnie Jackson, the banjo player for Buck Owens & the Buckaroos in the 1970s. More specifically, was he still living? While I haven’t located anything to suggest that he has passed away, I have not been able to locate him among the living. Truthfully, I had never heard of him before but when I started digging into his history, I found an interesting story.

Ronald “Ronnie” Jackson is a native of Beattyville in Lee County, Kentucky, a tiny community situated along the Kentucky River about 70 miles southeast of Lexington. He was born there on February 2, 1948. As a youth, he had two obsessions: the banjo and television westerns. Earl Scruggs was his favorite. Before his family obtained a television set in 1955, or when reception wasn’t very good, Jackson would ride his bike to a neighbor’s home to watch the Flatt & Scruggs show from WSAZ-TV in Huntington, West Virginia.

Finally, at age 12 in 1960, Jackson’s mother Artie purchased a banjo for him. It was tough going at first but a chance encounter with

J. D. Crowe in 1962 helped to set him straight. Crowe told him he was “leaving out the thumb string.” By 1965, he had advanced to the point that he shared a television program in nearby Bowling Green, Kentucky. It was billed as the Clyde Denny and Ronnie Jackson Show. The program only lasted a couple of months.

At age 19, Jackson headed to Nashville. Once there, he befriended Earl Scruggs, who then began to give him pointers about his playing. Eventually he found work as a studio musician and over time appeared on approximately 100 albums. In 1970, he talked his way into a guest spot on the Grand Ole Opry. After receiving a warm introduction from Roy Acuff, Jackson launched into a Scruggs favorite, “Train 45” (better known to many Scruggs fans as “Reuben”).

One of the listeners who was tuned into the program must have been Buck Owens, because he reached out to Jackson by phone a week later. Jackson drove to Memphis to meet Owens, who was on tour. He played “Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms” and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” Owens hired the 22-year-old banjoist as the next member of his Buckaroos.

The addition of a banjo to the Buckaroos fit into Owens’s plans as it was only a short time later that he recorded a bluegrass album, Ruby. In all, Jackson participated in over 20 recording sessions with Owens, either playing banjo or guitar. He also appeared as part of the cast of Hee Haw. Jackson was in and out of the Owens band several times but stayed until close to the time that Owens retired from the road in 1979. After leaving Owens, Jackson went to Las Vegas and developed a show that ran for 10 years. Then, it was off to Miami Beach where he spent an equal amount of time as an entertainer on cruise ships.

In 1995, Jackson put 30 years of research to use with the release of a book called Classic TV Westerns.

In 1996, Artie Jackson was in ill health and Ronnie moved back to Lexington to be nearer to her. He took what was in all likelihood his first non-performance job—a car salesman. His work from that time forward remains a mystery.

Over Jordan

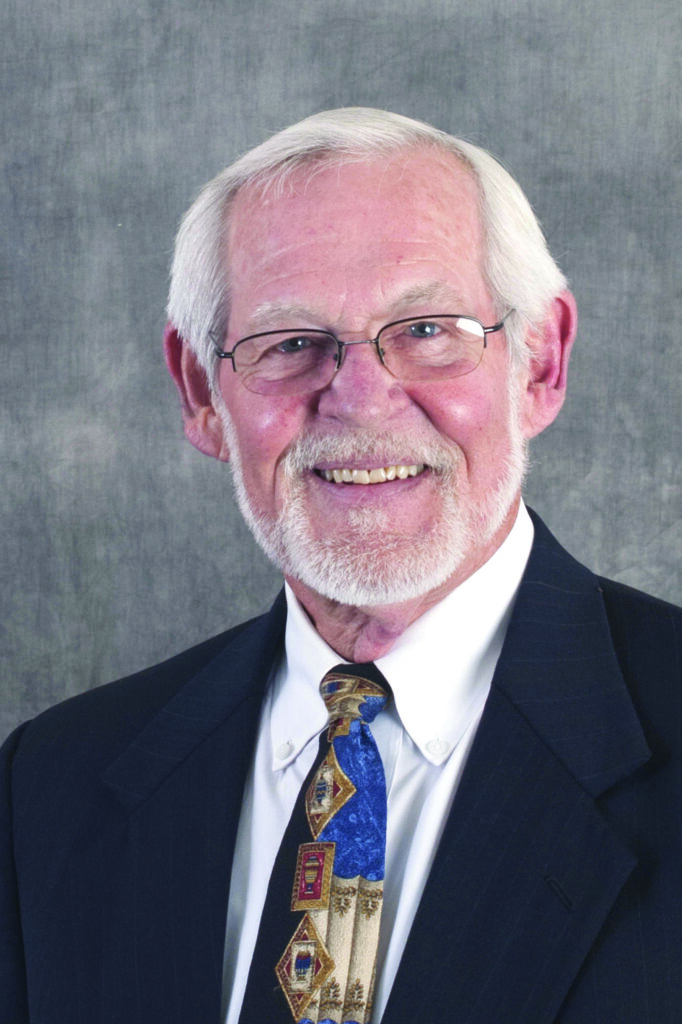

Wayne Mitchell Bledsoe (January 29, 1941 – June 2, 2024) was a 44-year bluegrass broadcaster, a 20-year magazine editor/publisher and a Kentucky Colonel. While these were his most high-profile accomplishments, they were but a few of many endeavors he undertook in the service of bluegrass.

Bledsoe was a native of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Pursuit of higher education took him from there to Mars Hill College in North Carolina; to Chattanooga where he graduated cum laude from Tennessee Temple University; and lastly to Lansing where he received a doctorate degree in history from Michigan State in 1969. Shortly afterwards, he settled in Rolla, Missouri, where he served as a professor of history at the University of Missouri.

Bledsoe’s radio career got underway in 1973 when he launched a program called Bluegrass For a Saturday Night. It aired over KUMR-FM. Popularity of the genre prompted the adding of a Sunday morning gospel program Sunday Morning Sounds. Although Wayne’s bluegrass shows represented only 3% of the station’s programming, they were, at its peak, responsible for 54% of listener pledges.

With 100,000 watts of broadcast power, Bledsoe’s programs were heard in neighboring states including Illinois, Kentucky and Arkansas. In addition to keeping in touch through the airwaves, Bledsoe instituted a bi-monthly newsletter that had a circulation of about 2,500 recipients. The publication went to individuals in 17 states and six foreign countries.

Experience with the radio newsletter came in handy with the formation of Bluegrass Now magazine in 1991. Impetus for launching the magazine was threefold: to highlight the growing influence of women in bluegrass, to draw attention to new bands and to promote the growing bluegrass music industry. The slick, full-color magazine succeeded on all fronts and had subscribers in all 50 states and 17 foreign countries. Two years after the launch of the magazine, Bledsoe received an Excellence in Business award from the Missouri Small Business Development Center. He also received IBMA’s 1996 award for Print/Media Person of the Year.

While continuing to teach full time, host two radio shows, and run a monthly magazine, Bledsoe found time to serve on the IBMA Board of Directors (1998-2005), author at least twenty album liner notes/CD booklet notes, contribute artist bios for Carnegie Hall appearances by Chris Thile and Edgar Meyer, sponsor the Fans’ Choice Bluegrass Awards at the Ryman in 1998, sponsor a recurring bluegrass stage at Silver Dollar City theme park in Missouri, organize IBMA Trade Show program sessions, make two trips abroad to help Moonshiner magazine with the promotion of bluegrass music in Japan, promote bluegrass concerts in Missouri during the 1980s and ’90s, and serve as a master of ceremonies at Fan Fest events during IBMA weeks in Owensboro, Kentucky.

As he advanced in years, Bledsoe phased out of a number of bluegrass endeavors. Bluegrass Now ceased publication in 2011 and he gave up his radio gig in 2017. Artifacts from his lengthy immersion in bluegrass are housed at the State Historical Society of Missouri in Rolla.

Arthur Martin “Artie” Rose (January 26, 1931 – May 28, 2024) was tagged by Bluegrass Unlimited contributor Dick Bowden as a “pioneer New York mandolinist.” He was that, and much more. A multi-instrumentalist, he recorded in 1950s and ’60s on Dobro, guitar and mandolin; was a member of several New York-based old-time, bluegrass, and jug bands; and was an avid photographer who captured on film many exciting images of the developing bluegrass scene in the Big Apple. After relocating to the West Coast, he became involved in the business side of bluegrass as a founding partner (with his wife Harriet, manager Craig Miller and mandolin guru David Grisman) of the Acoustic Disc label.

Music was a lifelong pursuit for Rose. It was also therapy. He was born with a condition called Erb’s palsy which gave him a severely atrophied right arm and hand with much-limited use. This affliction was a great motivating factor in his teen-years pursuit of learning a musical instrument as a therapy for his condition. His attachment to bluegrass, old-time and country music began in the early 1950s when he met and struck up a conversation with Harry West in a local record shop.

Rose’s music career got underway in 1956 when he recorded as part of an old-time/bluegrass band that was headed by Harry West and his wife Jeanie. The Wests were transplants from Virginia and North Carolina who brought their regional sound to New York City. The album Smoky Mountain Ballads was issued on the Prestige label with the subheading “assisted by ARTIE ROSE on STEEL GUITAR” (bluegrass fans would know the instrument more commonly as Dobro). His association with the Wests continued into the early 1960s when he appeared on two more Prestige albums: Roaming the Blue Ridge by Jeanie West (the first bluegrass album by a female) and Country Music in Blue Grass Style. Both albums were augmented by the banjo work of Bill Emerson and the bass playing of Tom Morgan.

The early and middle 1960s found Rose playing in a number of diverse groups and coming in contact with a variety of creative musicians. One of his most long-lasting relationships was developed in the early ’60s at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village. David Grisman asked Rose if he “could play his beautiful Gibson F-4 mandolin and he said ‘No!’” Grisman fondly remembered the encounter as “the start of a beautiful friendship!”

In the late fall of 1962, Rose collaborated with banjoist Tom Paley and guitarist Roy Berkeley to form the Old Reliable String Band. In the notes to their lone self-titled album on the Folkways label, the group described their aim as being for “the kind of sound achieved by the old-time string bands of the twenties and thirties, much the same sort of thing that the New Lost City Ramblers did when Tom was a member of that group.” On the album, Rose played guitar, mandolin, fiddle and Dobro.

A brief flirtation with jug band music took hold in 1963. First, there was Rose’s inclusion in Dave Van Ronk’s Ragtime Jug Stompers. Rose played mandolin and Dobro on the group’s self-titled major label release on Mercury. Next was the True Endeavor Jug Band which recorded The Art of the Jug Band for Prestige. Given that Rose was under contract to Mercury as a part of Dave Van Ronk’s group, his participation on the Prestige album was disguised with a pseudonym.

Rose’s last commercially-recorded trip to the studio in the middle 1960s was a single track on a various artists album for Elektra called String Band Project. Along with Peter Siegel, Gene Lowinger and David Grisman, Rose appeared on an instrumental tune called “Stoney Point.” A short time later, Rose participated in a series of home recordings with David Grisman that were later released on Sugar Hill as Early Dawg. The collected tracks, especially the Grisman original “Opus 38,” captured the essence of Dawg Music in its earliest stages of creation.

Photos from Rose’s growing archive of pictures began seeing the light of day in early editions of Muleskinner News. In a 1970 edition, editor Fred Bartenstein asked: “Have you noticed the quality of photography in the Muleskinner News? Our thanks are due to contributing photographers Barbara Boatner, Artie Rose, Ed Huffman, Jim McGuire and Ron Elsis.” Most recently, Bartenstein commented that “Artie took thousands of black and white photos, documenting the early NYC bluegrass scene, as well as the early festivals he attended. Artie generously shared these photos widely. If you put ‘Artie Rose photographs’ into a browser you’re likely to find numerous mentions.”

Rose returned briefly to Harry and Jeanie West in 1974. Two years later, he lent his Dobro talents to a Revonah album by Red and Rusty & the Pine Hill Ramblers.

Rose’s day job throughout all of this was with Abilities Inc., a trendsetting electro/technical assembly plant that employed predominantly handicapped people. He logged nearly 30 years there as a purchasing agent. But by 1989, it was time for a change. Harriet Rose related that “we always had a ‘California Dream’ but it didn’t come to fruition until we (David Grisman, Artie and myself) wanted to start a business. Artie and I were not just friends of David, but ardent fans of his music. We started Acoustic Disc in November of 1989 and put out our first release, Dawg 90, in June of 1990.” Being a small “family” business (as Harriet described it), Artie “had his fingers in most every aspect of the business side of the business, from purchasing, inventory, sales, marketing, shipping and even errands when needed.”

Making music continued to be, as had always been in the past, a top priority for Rose. More recently, however, a severe case of carpal tunnel syndrome in his left hand, coupled with the use of just two fingers on his other hand, necessitated that he give up the mandolin and guitar. Left with only the Dobro, he played, as Harriet described, “quite tastefully even with such drastic physical limitations.” She concluded, “Artie was indeed a special person and when anyone mentions his name, there’s sure to be a smile on their face.”