Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – August 2023

Notes & Queries – August 2023

Queries

Q: Do you know much (or anything) about the Armstrong Twins? I recently heard a track on a radio program from an old LP. I know that Floyd died in 1994; I have made many attempts to discover when Lloyd died. I met Lloyd at IBMA Louisville in 1997 and we had a long conversation about his feelings of the demise of the old country sounds. I plan on having a feature on my radio program dedicated to them. Norris Long, Allegheny Mountain Radio.

A: The Armstrong Twins, Floyd and Lloyd, were brothers who sported a mandolin/guitar duet at the same time (the 1930s) that other such duos – namely the Blue Sky Boys, the Delmore Brothers, and the Monroe Brothers – were popular. Unlike other brother duets, they were the only ones who were twins. Because much of their work took place on the West Coast, they were, for many years, underappreciated by the old-time and bluegrass communities at large. A series of reissue and new recordings from the late 1970s and early 1980s did much to enhance their reputation.

The Armstrongs were born in DeWitt, Arkansas, on January 24, 1930. At a very early age, the boys’ mother, who was a radio entertainer, began teaching them to sing. They began making guest appearances on local radio and at age seven had their program.

By 1947, the duo had been performing for nearly a decade. As many Mid-Westerners did during the 1930s and ‘40s, they relocated to the West Coast. There, they secured a Round-Up program on KXLA in Pasadena, California, a 10,000-watt station that went on the air in 1942.

From 1947 until 1950, the Armstrong Twins recorded at least twenty sides for Los Angeles-based 4-Star Records. Their recorded repertoire was a mix of songs recorded by other duets (such as “Garden in the Sky” by the Blue Sky Boys), early bluegrass favorites (including “Mother’s Only Sleeping” – recorded by both Bill Monroe and Charlie Monroe, “Bouquet in Heaven” and “My Cabin in Caroline” by Flatt & Scruggs, and “It’s Never Too Late” – most likely the first cover version of a Carter Stanley composition), and Armstrong originals (such as Floyd’s “Mandolin Boogie”). A few selections featured the twins with their sister, Patsy. Together, they were billed as the Armstrong Trio.

The 1950s found the twins rambling from California to Odessa, Texas; from there back to California; and eventually to their native Arkansas where they settled in Little Rock. It was there they got out of the music business and secured jobs as an auto mechanic and as a carpenter. They were lured out of retirement in the late 1970s when a reissue album of their early recordings appeared on the market. A newly recorded album (ca. 1980), called Just Country Boys, accentuated their old-time roots and proved that time had done little to diminish their talents.

Q: Can you tell me anything about the Rocky Mountain Boys who recorded “A Hundred Years From Now” and “Oh! Please Come Back”? Where were they from and can you name them and their instruments they played as well as the writer of “Oh! Please Come Back”? I believe these two songs were recorded in 1952. There was another band with the same name that recorded “Church of God” but I don’t know if they are the same Rocky Mountain Boys. Jerry Steinberg, Salem, Virginia.

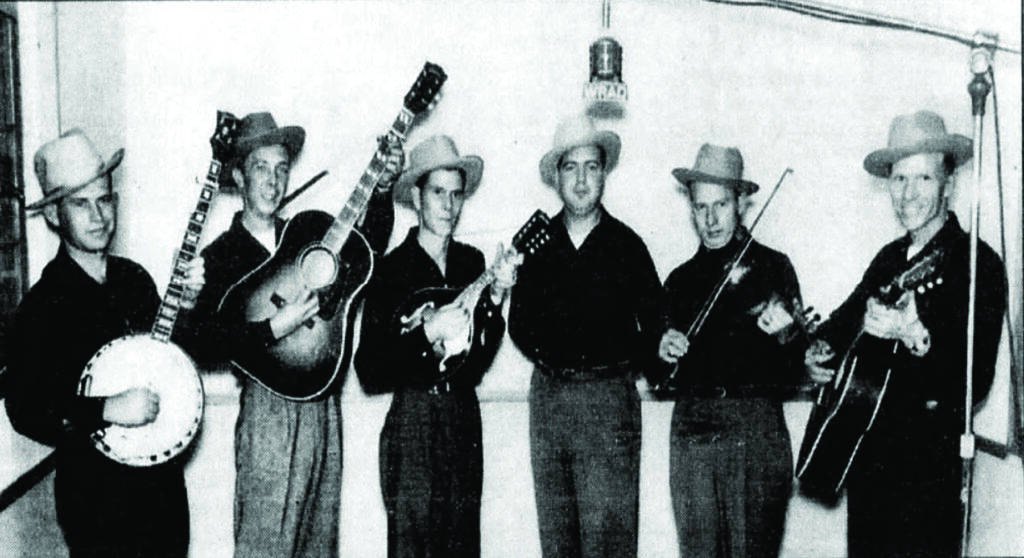

A: The Rocky Mountain Boys was a band that came together shortly after the end of World War II. They were headquartered out of Blacksburg, Virginia. A photo dated 1947 showed the group consisting of Avery “Red” Linkous on fiddle, Hubert Lovern on mandolin, Clifford Lovern on guitar, Jimmy Price on banjo, and Bobby Smith on guitar. Also pictured was Lewis Kanode who sponsored the group on radio and sometimes acted as a master of ceremonies. The group photo was taken at radio station WPUV in Pulaski, Virginia, where the band had a half-hour program.

In 1950, the Rocky Mountain Boys, along with announcer Kanode, moved to radio station WRAD in nearby Radford, Virginia, where they remained until 1954. It was while headquartered there that they recorded two songs for release on Rich-R-Tone Records, catalog number 1037. Researcher Matteo Ringressi pegs the date of release as around May 1952. The A side of the disc, “Oh! Please Come Back” was credited to Avery Linkous. The writer on the B side, “A Hundred Years From Now,” was left uncredited but that honor belongs to Red River Dave McEnery. The song dates back to August 1940 when it was first released by Bob Atcher and Bonnie Blue Eyes as “I Won’t Care (A Hundred Years From Now).” The Oklahoma Sweethearts covered the song in July 1947 but it was most likely a March 1950 release by Clyde Moody that introduced the song to the Rocky Mountain Boys.

Throughout the early 1950s, the Rocky Mountain Boys enjoyed a local following in Blacksburg and surrounding areas. Their work included performances for cake walks, lodge meetings, square dances, and school fundraisers. One noteworthy recurring engagement was the Friday Night Jamboree which was held at the Glen Theatre in Christiansburg, Virginia. The show was billed as a three-and-a-half-hour stage show that featured three hillbilly bands: Lewis Kanode and his Rocky Mountain Boys, Floyd Royal and his Little River Boys and Red Turpin and his Dixie Rangers.

A disagreement among band members in 1954 led to the breakup of the group. Lewis Kanode went on to enjoy a lengthy career as radio personality. Red Linkous wasted no time in forming a new group known as the Blue Ridge Valley Boys. He appeared on radio stations in Christiansburg, Radford, and Pulaski and also did television work in Roanoke. He passed away on July 4, 1967, at age thirty-nine, of an apparent heart attack.

Remembrances

Donald Yessay “Don” Kissil (December 16, 1933 – May 18, 2023) dated his involvement in bluegrass back to the middle 1960s. He started out as a fan and by his own admission, his talents were not with performing. Rather, they were with listening, which he then output as articles for magazines. He also developed a knack for concert promotion and photography.

Kissel’s outreach with bluegrass got underway in the early 1970s, with a trio of articles for Bluegrass Unlimited. “An Old Time Happening” (September 1970) recounted his family’s discovery of old-time pickers and singers at Silver Dollar City in Branson, Missouri. “Ramblin Thoughts on a Lemco Album and Two Live Concerts” (March 1971) chronicled a magical evening of music by Red Allen who performed in one of the now-legendary basement sessions in the New Jersey home of Loy Beaver. The article also hinted at what was the start of a massive collection of bluegrass photos. He only took twelve of Red that night but by 1980, Kissil’s stash of bluegrass slides numbered over 5,000. “Wow . . . Whata Wild, Wild, Winter Weekend” (May 1972) gave an accounting of one of Kissel’s early concert promotions. Rual Yarbrough and The Dixiemen, from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, ventured north to New Jersey only to be met with twelve inches of snow, temperatures dipping down to eight degrees, and a turnout of seven patrons! Kissil noted later, “You gotta do it for the love.”

It was during this same timeframe that Kissil’s photographs began appearing on album covers. The earliest was 1970’s A Bakers Dozen – Country Fiddle Tunes by Kenny Baker. Others that followed soon afterwards included Mac Martin & The Dixie Travelers – Dixie Bound (1974), Kenny Baker Grassy Fiddle Blues (1974), and Bill Clifton’s Come By The Hills (1975).

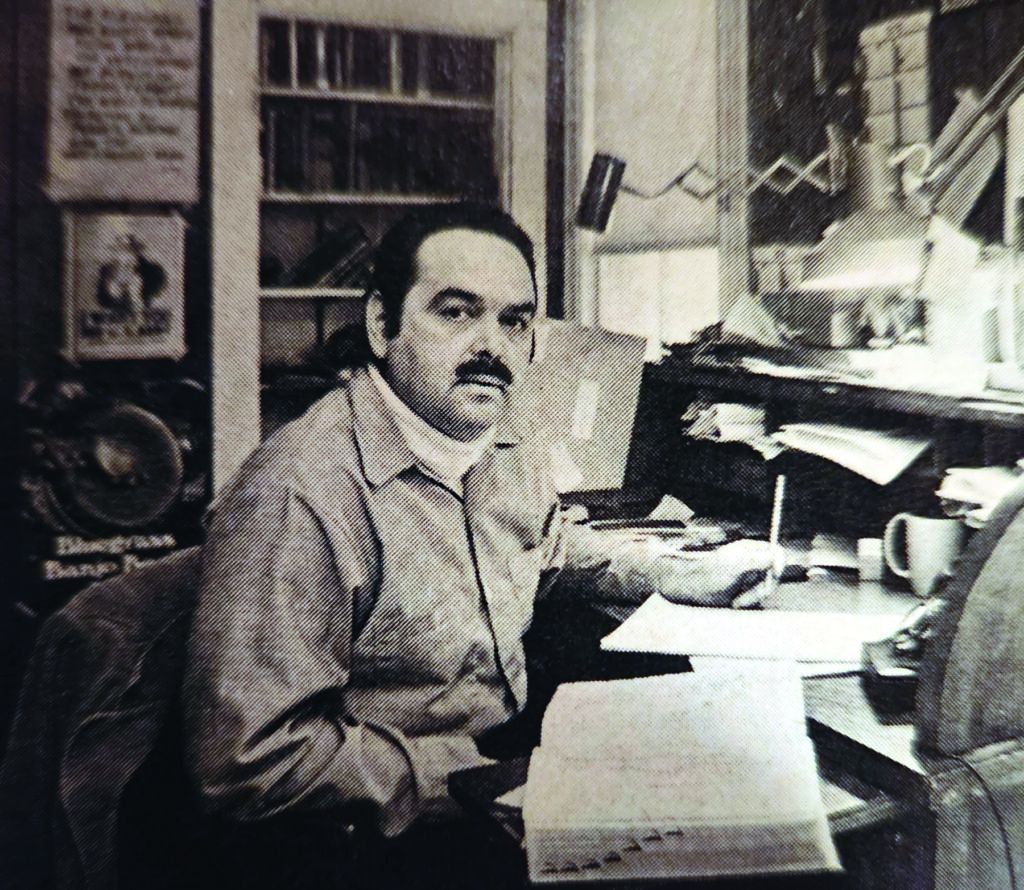

In 1974, promoter Doug Tuchman launched Pickin’ magazine. It was billed as “The Magazine of Bluegrass and Old Time Country Music.” Kissil’s photo of Bill Monroe that was taken at the 1966 Philadelphia Folk Festival graced the debut cover. He made several other contributions, both photos and articles, before being asked to take over the editorship of the magazine. It is for his work at the helm of the magazine, from October 1975 thru September 1979, that he is best-known.

The magazine was launched at a time when there were already two bluegrass publications on the scene, Bluegrass Unlimited and Muleskinner News. It was a daunting task adding a third to the mix. Under Kissil’s nearly four-year editorship, there were many excellent articles, photos, reviews, and more, and he saw the circulation rise from 6,000 to 50,000. But, there were trade-offs. In an attempt to reach a larger market share, Pickin dropped its bluegrass subheading and became known as the magazine “For People into Music.” He stepped down as editor and became part of an editorial advisory board but the appointment was short-lived; three months later (December 1979) the magazine printed its last issue.

In his other life, Kissil was a pharmacist, pharmacologist, and a ghost writer for medical publications. But, he continued to keep a hand in bluegrass with several concert promotions and at least a dozen articles for Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Now.

Samuel Mark Kuykendall (October 17, 1962 – June 19, 2023) is well-known for a series of recently-released albums on the Rebel label that paired him with legendary fiddler Bobby Hicks. Billed as Mark Kuykendall – Bobby Hicks and Asheville Bluegrass, the duo released Down Memory Lane in 2015 and Forever and a Day in 2017. While these releases are the most widely-distributed examples of Kuykendall’s songwriting, singing, and playing, he has a long history in bluegrass that belies his recent brush with notoriety.

Born into a musical family – his father Ed played banjo, his mother Dorothy played piano and sang, and his sister played clarinet – near Asheville, North Carolina, Mark began learning to play at an early age. In 1971, at the age of nine, he played guitar on recordings by banjo legend Raymond Fairchild. The middle 1970s were somewhat of a whirlwind. He left middle school at the age of fourteen to pursue a career in music. Some of his early performance experience included work with the Billy Graham Crusade, with Raymond Fairchild, and an appearance where he played mandolin on the Grand Ole Opry.

By 1979, Kuykendall was fronting his own band: Mark Kuykendall and Smoky Mountain Bluegrass. The following year, he released a solo album that included fabled fiddler Arvil Freeman and former Blue Grass Boy Ralph Lewis. The album was barely on the market when Kuykendall headed to Florida for work with Larry Rice. The early 1980s also found Mark performing with Larry Perkins and various pickers who had once been members of the Flatt & Scruggs group, the Foggy Mountain Boys.

In 1983, Kuykendall organized another outfit, called Mark Kuykendall and the Grass Cutters. The same year, he helped Ralph Lewis to record a five-song extended play disc. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Jon Hartley Fox cited Mark for having the “best lead work done” on the record on the Flatt & Scruggs favorite “The Old Home Town.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, Kuykendall toured with two of the best groups in bluegrass. He spent five years as a member of Jimmy Martin’s Sunny Mountain Boys. He credited Martin with teaching him valuable lessons about timing. Mark had the distinction of being the last bass player for Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys; his three-year stretch in the band ended with Monroe’s 1996 stroke that ended his career.

It was after Monroe’s illness that Mark took a nearly twenty-year break from bluegrass. It afforded him an opportunity to ramp up his other passion, collecting, trading, and selling vintage automobiles. Over the years, he had vehicles that once belonged to celebrities such as Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. He auctioned off the Elvis car in 2006 to cover the costs of a 19th century farmhouse renovation in Sevierville, Tennessee.

At six feet, nine inches tall, Kuykendall cut a commanding presence. Although plagued for years with vascular problems and diabetes, he told Knoxville’s News Sentinel that he’s still “the most blessed man in the world . . . Without the Lord, family, and friends, you have nothing. It doesn’t matter how much money you have.”

Laslie Bryan “Les” Leverett (April 23, 1927 – June 2, 2023) was a native of Atmore, Alabama, who was, for many years, a staff photographer for the Nashville-based National Life Accident and Insurance Company, the parent organization for the Grand Ole Opry, radio station WSM, and WSM-TV. From the early 1960s until the early 1990s, Leverett’s photographic work was the face of these legendary outlets for country music.

After serving in the military in the middle 1940s, Leverett built upon a childhood interest in photography by attending the Texas College Photographic Art in San Antonio. Shortly after marrying in 1949, he and his new bride, Dot, moved to Nashville where he secured work with Associated Photographers and later with Frederick’s Studio. It was through Frederick’s that he wound up at the Opry.

Among his early work highlights were opportunities to travel with, and photograph, Opry stars. One memorable outing included a Carnegie Hall concert that featured Bill Monroe, Patsy Cline, Grandpa Jones, and Marty Robbins. Another was a week’s worth of dates with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs as they traveled in their custom bus throughout the Deep South. One of Leverett’s most iconic photographs was made on that trip. It was a candid shot of the Flatt and Scruggs group chowing down at a rural lunch counter.

In addition to photographing a host of mainstream Opry performers, Leverett also snapped pics of numerous bluegrass performers, most notably those who were part of the Opry cast: Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, Jim & Jesse, and the Osborne Brothers. Starting in the early 1970s, when the Opry featured its jam-packed Early Bird concert series, Les added other bluegrass legends such as Ralph Stanley and the trio of Don Reno, Bill Harrell, and Red Smiley to his photographic archive.

Leverett is credited with creating photography for over two hundred album covers. At least one was a Grammy winner, a 1966 album by Porter Wagoner called Confessions of a Broken Man. His bluegrass album cover credits included two for Lester Flatt (Foggy Mountain Breakdown in 1972 and Bluegrass Festival in 1974); two that featured Earl Scruggs (Classic Bluegrass Live, 2002) and Earl Scruggs – Doc Watson – Ricky Skaggs (The Three Pickers, 2003); and the booklet for a Bill Monroe boxed set on Bear Family (1970-1979) featured a number of Leverett images.

In 1996, country music scholar Charles Wolfe worked with Leverett to assemble a book of photos titled Blue Moon of Kentucky: A Journey Into the World of Bluegrass and Country Music. A later book, American Music Legends was distributed through the Cracker Barrel restaurant chain.

Leverett’s photos were the subject of several exhibits. One coincided with the opening of the bluegrass museum in Owensboro. Another, called Family Reunion: The Opry Family Photo Album, was housed at the Acuff House in Nashville.

Perhaps the most widespread, and most recent, exposure given to Leverett’s work came in 2019 when filmmaker Ken Burns used over eighty of his photos for his Country Music documentary.

For a lifetime of work documenting bluegrass music in pictures, the International Bluegrass Music Association presented Les Leverett with a 2001 Distinguished Achievement Award.

Margie Brewster Sullivan (January 22, 1933 – May 31, 2023) enjoyed a lengthy six-decade career in bluegrass as a performer with the Alabama-based Sullivan Family gospel singers. A native of Winnsboro, Louisiana, she developed a love for music from her guitar-playing father. When Margie was around age eight or nine, he showed her her first chords on the guitar. She never sought to be a flashy instrumentalist but used the guitar to support her singing. In 2006, she told Murfreesboro’s The Daily News-Journal, “I loved to sing. I could express myself so much better singing than talking. Singing . . . it’s my first love.” At age thirteen, Margie’s father passed away. With her mother’s blessing, she hit the road with a traveling evangelist named Helen Chain. They appeared at revivals throughout the Deep South. It was at one such event that Margie met her future husband, fiddle playing Enoch Sullivan. They married three years later when she was sixteen and he was eighteen.

It was at this time, 1949, that Margie joined the Sullivan Family, which was then headed by Enoch’s older brother, Arthur Sullivan. The group appeared on several radio stations and performed musical ministries at area churches. During this same period, Enoch held down a day job as an engineer for a firm in Mobile, Alabama, and Margie gave birth to the couple’s five children. When Arthur passed away in 1957 the leadership of the group passed to Enoch. The following year, he resigned from his day job and the Sullivan Family became full-time entertainers.

Throughout the late 1950s and most of the 1960s, the group played to audiences in the Deep South. In 1968, they performed at Bill Monroe’s festival in Bean Blossom, Indiana. Monroe was the first person to identify the group as “bluegrass gospel.” They met with overwhelming approval from the festival’s attendees and soon found themselves enjoying a brisk trade on the bluegrass festival circuit.

The Sullivan Family began making recordings in the late 1950s. First as 78 rpm discs, then 45s, and then long play albums. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer George B. McCeney noted that “this family group has managed to regain the power and style of gospel singing as it was recorded thirty years ago (in no small way due to the voice of Margie Sullivan).” Earlier female singers such as Molly O’Day, Kitty Wells, and Martha Carson served as inspiration for Margie in developing her own robust style. She eventually became known as the First Lady of Bluegrass Gospel.

At their peak, the Margie and the Sullivan Family worked approximately 300 show dates per year, which included a mix of church musical ministries, bluegrass festivals, and even dates in Europe. Enoch and Margie also operated two annual bluegrass festivals on property they owned in St. Stephens, Alabama. Along the way, they also served as a proving ground for up-and-coming bluegrass musicians, most notably Marty Stuart and Carl Jackson.

In 2005, the Sullivan Family received several honors. The Alabama State Council on the Arts conferred its Alabama Folk Heritage Award upon the group while the International Bluegrass Music Association bestowed a Distinguished Achievement award.