Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – August 2021

Notes & Queries – August 2021

Notes

“In response to Mary Gibson’s question about the Webster Brothers in the May issue of Bluegrass Unlimited, I was just listening to them the other day on an album called Classic Country Duets (Old Timey 126). It’s a nice album with 17 songs that had long been unavailable and includes ‘Road of Broken Hearts’ and ‘Seven Year Blues’ by the Webster Brothers. Other acts on the album include the Dixon Brothers, Blue Sky Boys, Delmore Brothers, Girls of the Golden West, Dezurik Sisters, Bailes Brothers, Buchanan Brothers, Armstrong Twins, and Johnny & Jack. For someone wishing to sample a variety of the close harmony singing of the 1930s through early 1950s, I recommend this album. It’s also still available as a CD or vinyl LP.”

Joe Ross, Roseburg, Oregon

Queries

Q: “Back in the late 1940s or early ‘50s, there was a historic show in Corbin, Kentucky, with Bill and Charlie Monroe and their bands. Each did a show and then they came out together. The story goes that it was first time they had spoken in nine years. Any information on the show, the band members, etc. is appreciated. Thanks.” Bob, via email.

A: In his book Bill Monroe: The Life and Music of the Blue Grass Man, Tom Ewing wrote that “on Sunday, September 16, 1951, Bill played a show with brother Charlie for the first time in nearly thirteen years, at the YMCA Auditorium in Corbin, Kentucky. It was the first of a series of shows that week featuring the brothers with their bands and as a duo.” Tom’s book offered some clues as to who might have been in Bill Monroe’s band: South Salyer on guitar, Joe Drumright on banjo, and Oscar “Shorty” Shehan on bass. We reached out to Tom for confirmation. He replied that “all of the musicians you’ve named were working with Bill in September 1951, but whether they were actually with him at the reunion isn’t known for sure. Also, Gordon Terry may have fiddled with the Blue Grass Boys.” Charlie Monroe worked in Knoxville, Tennessee, during the summer of 1951. There, he had daily radio broadcasts over WNOX and also appeared on the Saturday evening Tennessee Barn Dance. Photos from this era suggest that his band at the Corbin show could have included mandolin player Ted Mullins, steel guitar player Buddy Osborne, fiddler James G. “Slim” Martin, banjo player Joe Medford, and bass player Wilma Martin. Country Song Roundup magazine reported that “crowds traveled hundreds of miles to see the Monroe Brothers together again.”

Q: “I’ve been trying to figure out exactly who accompanies Walter Hensley on his early ‘60s banjo album, The Five String Banjo Today on Capitol Records. In a 2003 article in Bluegrass Unlimited, he mentioned Boots Randolph [on saxophone], The Jordanaires, as well as Tommy Jackson on fiddle for this album. (He would have preferred to have Benny Martin.) Walter didn’t mention the other musicians but said they were great. Any idea who they were?” Joe Ross, Roseburg, Oregon

A: Using a couple of different sources, we were able to cobble together most of the personnel for this album. In 2008, a contributor to the Banjo Hangout website (identified as 56 Gibson Hoss/Tom in Tulsa) posted that “many years ago I played with Earl Taylor and the Boatwhistle (Vernon McIntyre, Sr.) and Boat told me that he played bass, and Jim McCall was the guitar player on many of the songs.” More recently, we reached out to bluegrass band leader James Reams, who recorded two CDs with Walter Hensley. James related that “Walter told me Floyd Cramer played piano and Red Rector played mandolin. Not sure who played drums; I’m sure a popular studio drummer at the time. Walter had a completely different concept for the album but Capitol Records executives prevailed.”

Indeed, it was producer Marvin Hughes, who had recently resigned as the music director of the Grand Ole Opry staff band, who orchestrated Walter’s recording sessions. The album made its debut around September 1964 and pre-dated publications such as Bluegrass Unlimited and the County Sales Newsletter. Syndicated newspaper columns by well-meaning, but mostly uninformed, reviewers offered brief mentions of the album. Linda Norris, in her “Let’s Look at the Records” column told that “country and folk music authority Alan Lomax called Walt Hensley a man who has true folk magic in every note he plays. In ‘The 5-string Banjo Today,’ his first Capitol album, he displays how the instrument can have a modern, or pop sound, without losing its authenticity.” William D. Laffler, in his UPI “Popular Records . . .” weekly noted that “here’s a made-to-order LP for banjo buffs, folk bugs and sentimentalists.” Likewise, James Wilber, in his Cincinnati Enquirer column “The Popular Beat” raved that “if you like your banjo 5 string style this album is for you. Walter Hensley is an expert at this unusual skill and clearly shows his technical ability and ‘bluegrass’ conception.”

Only a few seemed to grasp the unique nature of Walter’s album. Larry Daugherty of the Nashville Tennessean ran the headline of his “On the Record” column with “Sorry, Friend-It’s Just Not Country Anymore.” He editorialized that “the musical output of the country and western artists can no longer be separated from the so-called popular field, and the sounds coming from Nashville recording studios sometimes represent a solid contribution to music at large.” He offered Walter’s album as an example. “Although Hensley has played from the Grand Ole Opry to Carnegie Hall, this is his first album, produced here by Marvin Hughes and backed on some numbers by the Jordanaires. Many music students have called the five-string . . . America’s only national instrument, and until recently it had fallen into disuse as the chief instrument of minstrel shows . . . The efforts of Earl Scruggs, and now Hensley, are restoring the banjo to its proper position as an instrument worthy of the concert stage.” But the most discerning reviewer of the lot was Western Folklore’s Ed Kahn. In his “Review: Folk Song Discography,” he cautioned that “one of the worst records featuring the 5-string banjo to come out in some while is The 5-String Banjo Today (Capitol T 2149). As the notes warn us, Walter Hensley is helped along by ‘ . . . those wonderful singers, the Jordanaires, who sing both with and without words, and a where-did-he-come-from saxophone . . .’.”

Q: “Who recorded the hillbilly song ‘Everyone Knew It But Me’? Lester Flatt sang it when he was a Blue Grass Boy back in the ‘40s.” JS, Salem, Virginia

A: The song was recorded in mid-December 1946 by Jimmy Wakely. A January 1947 blurb in Billboard told that “Capitol [Records] this week adds Jimmy Wakely to its recording catalog. Pic player and former Decca Western warbler signed a long-term pact with the Coast diskery and will bow in on its label with Somebody’s Rose and Everyone Knew It But Me. Wakely first gained attention for his radio work in Oklahoma City. Since then he has worked on Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch CBS air show for two years, on numerous coast-to-coast broadcasts as a guestar, Decca records and gets star billing in Monogram Pictures’ oaters.”

Lester Flatt’s performance of the song is one of many air checks (recordings) that were made of Bill Monroe’s group. Collector Robert Montgomery reports that “the number of unique surviving radio performances by Monroe from the 1946-’48 period with Flatt and Scruggs in the band is well over 200.” He noted that the recordings came from three main sources. A few tracks came from transcribed editions of the Prince Albert Tobacco portion of the Grand Ole Opry. These programs were broadcast nation-wide on the NBC radio network, from 1939 to 1960. Montgomery reported that “only two or three shows from this period featured Monroe as a guest and are a very small portion of Monroe’s total surviving catalog.”

Earl Scruggs was responsible for the recording of about twenty songs. Montgomery confirmed that “Scruggs did pay to have some of these made, as I understand for one dollar per song. I’m thinking that Neal Matthews (a 1940s member of the Crook Brothers band and the father of Jordanaires second tenor Neal Matthews, Jr.) had an on-demand recording service for fellow Opry performers and made these for Scruggs. Most of these were issued on a bootleg Bluegrass Classics album (that entire album is drawn from Scruggs’ recordings).”

Lastly, it was a cadre of home recordists who captured most of these performances. “The VAST majority of surviving Monroe material from this time period was made by fans who owned home disc cutting machines and recorded for themselves from the radio. This material widely varies in quality, but almost all is worse quality-wise than the two sources I previously mentioned.” A number of these radio performances can be found on YouTube.

Q: “How many bluegrass performers have received an honorary doctorate degree from a college or university?” DM, Columbia, Missouri

A: As best that can be determined, it appears that a total of twenty-one honorary doctorates have been issued to seventeen bluegrass performers; three recipients (Ralph Stanley, Earl Scruggs, and Ricky Skaggs) received multiple honors. Ralph Stanley led the way in 1976 when he received an honorary Doctor of Music degree from Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee. Only two other performers received honorary degrees in the late 1900s: Earl Scruggs and Hazel Dickens; the rest came in the early 2000s. The list below gives a complete rundown, by date.

1976 Ralph Stanley Doctor of Music Lincoln Memorial University Harrogate, TN

1986 Earl Scruggs Doctorate of Humanities Gardner-Webb College Boiling Springs, NC

1998 Hazel Dickens Doctor of Humanities Shepherd College Shepherdstown, WV

2002 Ricky Skaggs Doctorate of American Heritage Arts Hocking College Nelsonville, OH

2005 Earl Scruggs Doctorate of Music Berklee College of Music Boston, MA

2005 Ricky Skaggs Doctorate of Humanities Eastern Kentucky University Richmond ,KY

2008 Ricky Skaggs Doctorate of Music Berklee College of Music Boston, MA

2010 Doc Watson Doctor of Music Berklee College of Music Boston, MA

2012 JD Crowe Doctor of Arts University of Kentucky Lexington, KY

2012 Alison Krauss Doctor of Music Berklee College of Music Boston, MA

2014 Ralph Stanley Doctor of Music Yale University New Haven, CT

2015 Leigh J. Gibson Doctor of Fine Arts State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY

2015 Eric I. Gibson Doctor of Fine Arts State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY

2016 Steve Gulley Doctor of Music Lincoln Memorial University Harrogate, TN

2019 Sam Bush Doctor of Fine Arts Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, KY

2019 Jesse McReynolds Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

2019 Jim McReynolds Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

2019 Bob Osborne Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

2019 Sonny Osborne Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

2019 Mac Wiseman Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

2019 Buddy Griffin Doctor of Fine Arts Glenville State College Glenville, WV

Q: “Before moving to Vermont around 1970 I lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan. While there, I played with a local band, The County Line Boys, and once in a while with Nolan Faulkner and Doug Green. Thinking about the recent Bluegrass Unlimited article about Appalachian people who migrated north for factory work, I remembered a band that played around southern Michigan and did a bit of recording, Curly Dan and Wilma Ann and the Danville Mountain Boys. Their song ‘South on 23’ really captured that feeling of longing for a home back in the mountains. My band and a few others in the area picked up that song and performed it as well. Apparently, they recorded a follow-up, ‘North on 23.’ Do you have any info on Curly Dan and Wilma Ann? They had a good, authentic down-home mountain style. Like Red Ellis and others who ended up in southern Michigan they were the real deal.” Dan Linder, Vermont

A: Curly Dan and Wilma Ann were, indeed, long-time fixtures of the southern Michigan bluegrass scene. The co-headliners were West Virginia natives who migrated to Michigan in the early 1950s. Densile Ray “Cury Dan” Holcomb was born in Clay County, West Virginia, September 12, 1923, while Wilma Ann Lowers was born in Charleston, West Virginia, on August 11, 1924. At age thirteen, around 1939, Curly Dan began his musical career by appearing with the trio of Cap, Andy, and Flip (mentioned in the July “Notes & Queries”) on radio WCHS in Charleston.

The book Detroit Country Music by Craig Maki and Keith Cady contains a complete chapter devoted to Curly Dan and Wilma Ann and mentions, among many other things, that the couple met in the early 1940s while they were both in Maryland looking for work; they married at the end of 1942. The couple returned to West Virginia where Curly Dan spent the next ten years working in coal mines. After moving to Detroit in 1952, Curly Dan secured work with Chrysler and organized a group called the Danville Mountain Trio. Early band members included mandolin player Bill Napier (who later worked with the Stanley Brothers from 1957 to 1960) and banjo picker Jim Maynard. The trio did a lot of club work in the Detroit area and in 1956 recorded the group’s first single: “Sleep, Darling” b/w “My Little Rose.”

Wilma Ann became more active in the group by the late 1950s/early ‘60s. She played bass, sang, and was credited with co-writing some of the band’s original songs. A 1963 collaboration between Curly Dan and Wilma Ann became somewhat of a minor hit: “South on No. 23.” Set to the tune of the Carter Family’s “My Little Home in Tennessee,” the song told of wistful memories of life in West Virginia. Initially recorded for the Michigan-based Happy Hearts imprint, demand was so strong that label owner Laverne Wright had to re-press the 45-rpm disc. In time, the group recorded the song on four separate occasions, including a 1964 re-make for Starday Records’ budget line, Nashville. This led to an invitation to appear on as guests on the Grand Ole Opry.

Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, a number of notable Detroit-based musicians passed through the band. Among them were mandolin players Frank Wakefield and Wendy Smith and banjo player Ford Nix, and guitarist Carmon Flatt, who was reported to be a second cousin to Lester Flatt.

In the early 1970s, Curly Dan and Wilma Ann recorded three albums for Old Homestead. The first of them was titled after their “hit” song, “South on 23” and featured Curly Dan on guitar, Carmon Flatt on guitar, Wayne Honeycut and Bill Carpenter on dobro, Wilma Ann on bass, and Bill Napier 12-string guitar, banjo, and guitar. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer George B. McCeney described the group as being “from another era” and left it to the reader to decide if that was good or bad; he compared Curly Dan to early Lester Flatt (“complete with echo”) and noted that all but one of the songs in the album were original.

In reviewing the group’s second album, A Place on the Mountain, Walt Saunders tagged it as being “steeped in the traditions and religion of West Virginia’s coal fields . . . [and] reflecting an intense religious faith and often revealing a nostalgic longing for their native Clay County.” He further noted that an “outstanding feature of this record is the presence of some fine sidemen, [including] Bill Napier, who provides the lead guitar.” In fact, Napier appeared on all three of the group’s albums.

John Roemer praised Curly Dan and Wilma Ann, as heard on New Bluegrass Songs, for being “a traditional bluegrass group which can perform all original material. Most of the songs here are reworkings of standard ideas, with a strong emphasis on longing to return to the south.” He touted the group’s duets and harmonies as being “bluegrass the way it’s s’posed to be sung, and it gives the record a bite and drive which lift it out of the ordinary.”

Despite their prolific output as songwriters and the exposure generated from their three Old Homestead albums, Curly Dan and Wilma Ann remained a regional act in southern Michigan. Curly Dan suffered a heart attack in 1976 and Wilma Ann was “having a hard time” from a brain aneurysm. With declining health, the duo retired from music in 1984. Curly Dan suffered a debilitating stroke in 1992 but continued to write songs by dictating them into a tape recorder; he died seven years later in 1999. From that time forward, Wilma Ann’s bass rested untouched in a corner until her passing in 2008.

Over Jordan

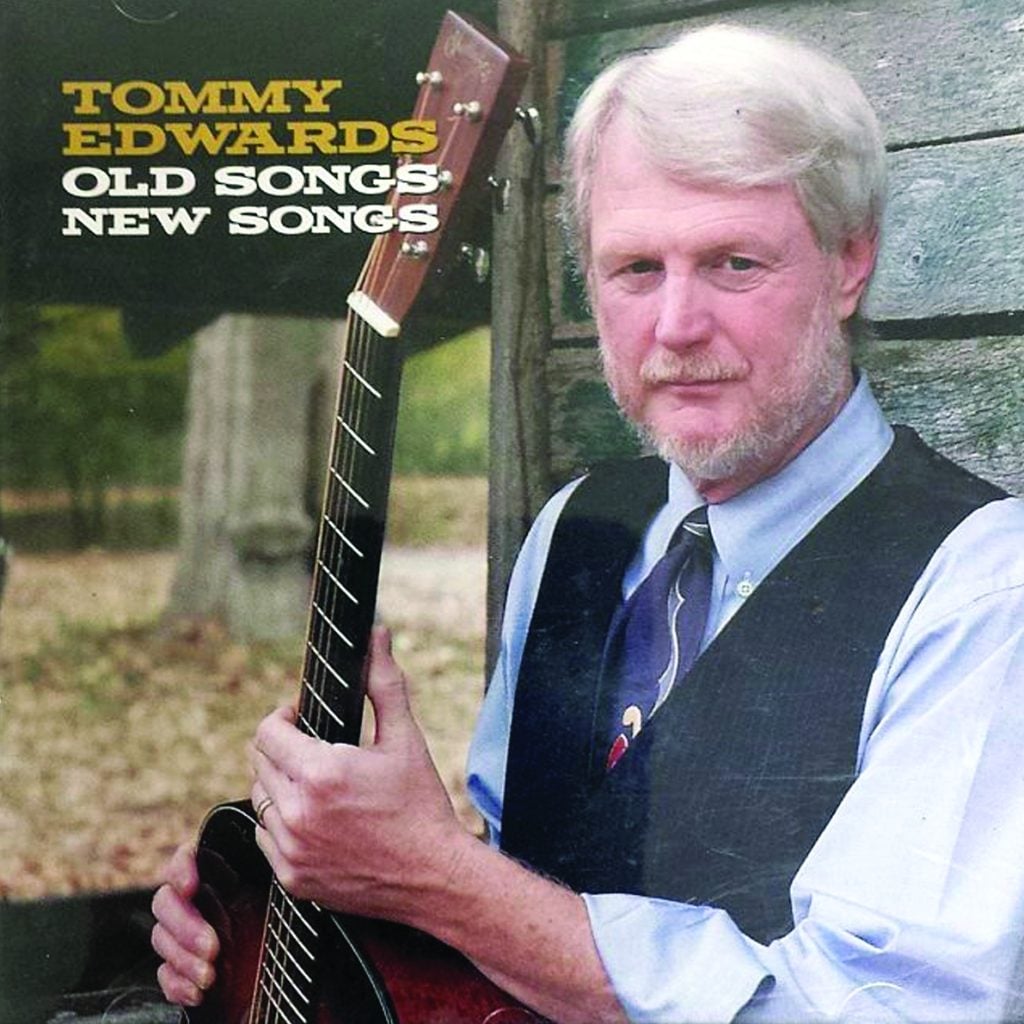

Thomas Shelton “Tommy” Edwards (July 20, 1945 – May 22, 2021) was a long-time fixture of the North Carolina bluegrass scene who co-founded and maintained the band Bluegrass Experience for fifty years. A native of Siler City, North Carolina, he came of age with the birth of bluegrass and noted that he was born the same year that Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. He gained his early training in a band called the Green Valley Ramblers. The Bluegrass Experience came together in 1971, at the same time that contemporary groups such as the Seldom Scene and New Grass Revival were coming into existence. The group name was coined by Leroy Savage, who borrowed it from the Jimmi Hendrix Experience.

Tommy had an infectious enthusiasm for bluegrass, and is credited with introducing scores of people to the genre. He was known as a forceful guitarist who combined witty humor, a crowd-pleasing repertoire (that included his original compositions, bluegrass standards, and popular songs adapted to bluegrass) and robust vocals, to arrive as a highly entertaining bluegrass performer. Among his witticisms, as told to Mary Cornatzer of Raleigh’s News & Observer, was his retort to fan requests for “Cripple Creek”: “We don’t do invalid numbers.” Or, when introducing a song by someone such as Hank Williams, he would deadpan that “We’d like to do a song written by a dead man . . . Actually, he wasn’t dead when he wrote it. Makes for a much better song.” And perhaps he was only partly poking fun when he observed that there are only four kinds of bluegrass songs: those of lost love, trains, death of a small child, and home.

Tommy and the Bluegrass Experience met with instant local acclaim. The group took top place honors at the 1971 Union Grove Fiddlers’ convention. Tommy won Best Guitar two years in a row. The band landed a nine-year gig at the Cat’s Cradle in Chapel Hill where it held forth every Thursday evening. The show attracted everyone from college students to rank-and-file bluegrassers and even those who didn’t necessarily like bluegrass, but who liked the Bluegrass Experience. The group also logged its fair share of college dates and even journeyed to Finland to participate in a national folk festival.

The Bluegrass Experience recorded at least four albums and CDs together including Collection, Live at the Pier, Experience This, and Respect For Tradition. Tommy also recorded several solo projects, among the more recent of which was North Carolina History, Mystery, Lore & More; it combined his love of bluegrass and love of history (his thirty-year day-job was as a teacher of history to middle school students).

When not playing music or teaching, Tommy could be found helping out at an antique shop in Pittsboro, North Carolina, that he ran with his wife, Cindy.

Amazingly, over the group’s fifty-year history, the Bluegrass Experience had just twelve full-time members. Tommy likened the band to being a support network. He confided to Mary Cornatzer that “we just really like each other. I think I’ll be playing forever and they’ll always be my friends. We’ll keep each other in our lives.”

For a lifetime of dedication to bluegrass and for promoting and preserving North Carolina’s musical traditions, North Carolina governor Roy Cooper awarded Tommy the state’s highest civilian honor, the Long Leaf Pine award, just one day prior to his passing.