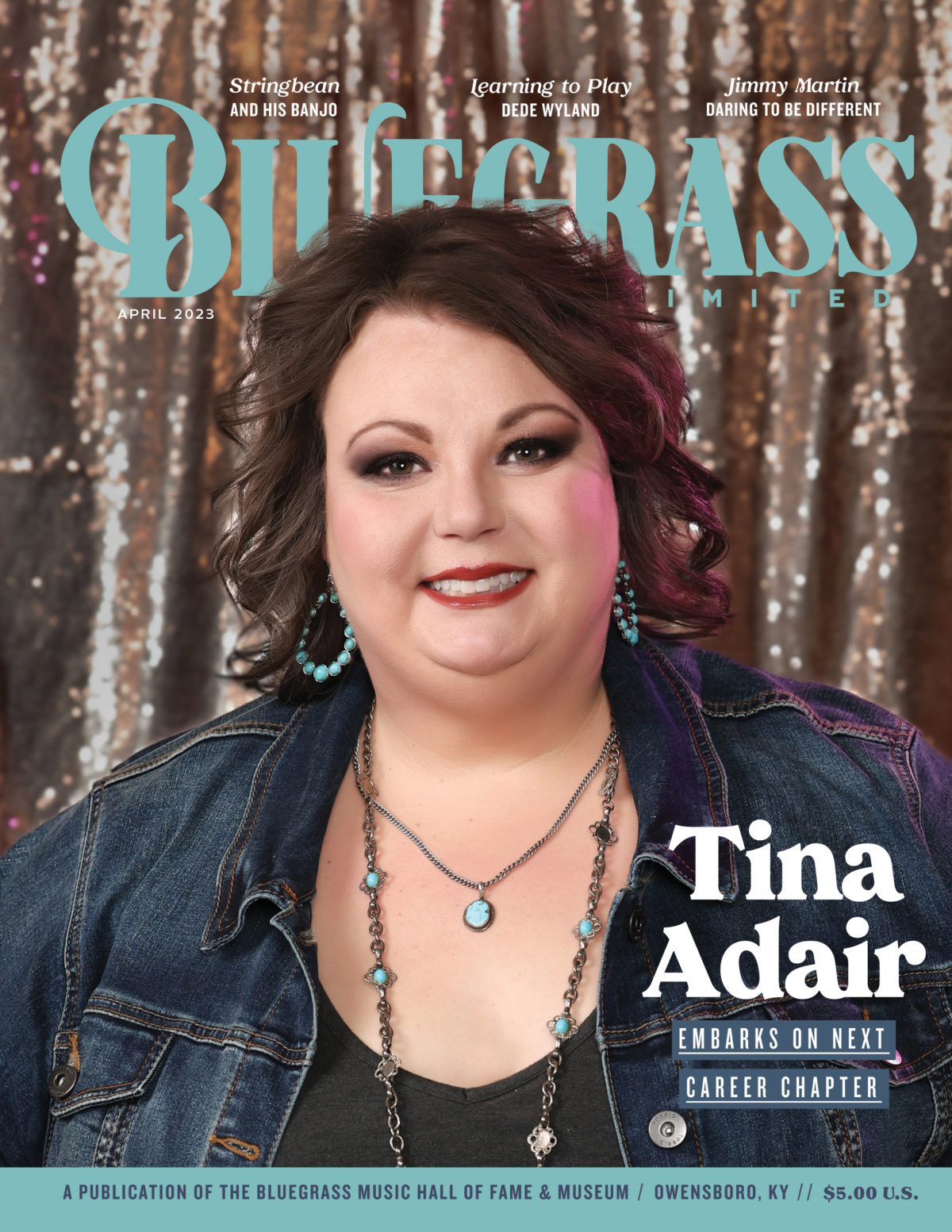

Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – April 2023

Notes & Queries – April 2023

Q: I have a question that I have been looking to have answered for years. Most people agree that the “Salty Dog” is/was a road house/tavern/speak-easy. The song “Salty Dog Blues” is an old bluegrass favorite with more than one person claiming authorship. After some investigation I have determined that the likely author(s) are the Morris Brothers, Wiley and Zeke, who I believe lived in Black Mountain, North Carolina. My question is: where was the “Salty Dog”? The closest I have come is a quotation from one of the brothers who said they had played a performance in a location west of Waynesville, North Carolina, and on the trip home they stopped at the “Salty Dog,” which was between Waynesville and Canton, North Carolina. These towns are fairly close together so I hope someone could shed some light. David Stori, via email.

A: Most of what we know about the creation of the “Salty Dog Blues” comes from an excellent article by Wayne Erbsen (Bluegrass Unlimited, August 1980) called, simply, “Wiley and Zeke – the Morris Brothers.” In it, he recounted that the song was written by Zeke Morris, in 1935, and that it was arranged by both Wiley and Zeke. The first recording of the song was in September 1938 at a session in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Zeke Morris said that “I got the idea when we went to a little old honky tonk just outside of Canton which is in North Carolina. We went to play at a school out beyond Waynesville somewhere and we stopped at this place. They sold beer and had slot machines. At that time they were legal in North Carolina. We got in there after the show and got to drinking that beer and playing the slot machines with nickels, dimes and quarters. I think we hit three or four jackpots. Boy, here it would come! You know you had a pile of money when you had two handfuls of change. The name of that place was the ‘Salty Dog,’ and that’s where I got the idea for the song. There’s actually more verses to it than me and Wiley sing, a lot more verses.”

One possible clue to the Salty Dog’s location was found in the January 8, 1951, edition of The Waynesville Mountaineer newspaper. Page three ran an article under the headline “Deputies Seize Bonded Liquor In West Canton Raid.” The article went on to tell that “Sheriff’s officers seized several pints of bonded whiskey Friday afternoon in a liquor raid on a West Canton service station known as ‘The Salty Dog’.” Of course, this was sixteen years after the song was written. Was this THE Salty Dog? Or, an establishment that cashed in the song’s later popularity?

A query to the Haywood County Historical Society elicited a reply that “no one remembers the exact location of the Salty Dog.” A staffer did point out that a 2016 book by Edie Burnette called Mountain Echoes contained a chapter called “Infamous Salty Dog Inspires Song.” It repeated much of the same information found in Wayne Erbsen’s article, but added that “the Salty Dog and surrounding buildings were demolished to make way for US 19/23 (New Clyde Highway).”

Recounting some of her own detective work, Burnette wrote in her book that “this week, I drove on Old Clyde Highway into West Canton. There were some older structures in that vicinity, but when I looked them up in the Haywood County records, none of them were old enough to have been around in the 1930s. So, whether the exact location was on Old Clyde Highway or along the route of the adjacent New Clyde Highway, the structure did not survive.” She concluded that “collective memories can’t recall ownership or exact location of The Salty Dog, but Bill Boyd, eighty-two, said ‘I was just a child at the time, but I remember it was a pretty rough place’.”

Q: Piano player Newton Thomas, who had a Big Band in Charlotte, North Carolina, for some years, told me part of the story some time back (thirty years, maybe) about writing “Till the End of the World Rolls ‘Round.” I’m interested in the “Rest of the Story” about him. He said that when Dutch (a 1991 movie with Ed O’Neill) came out, he received a check for $10K for the use of the Flatt & Scruggs recording in the film. Joe Cline, via e-mail.

A: Despite having been an integral part of the repertoire of one of the seminal bands from the early days of bluegrass, very little has ever been written about “Till the End of the World Rolls ‘Round” or its writer, Newton Thomas.

Newton Slater Thomas, Jr. (December 2, 1928 – January 27, 2005) was known primarily as a jazz musician/pianist and composer. He often fronted his own group that, throughout the 1950s, was variously known as the Newton Thomas Quintet or the Newton Thomas All-Stars; the latter was an apt group name as Thomas served as the president of the American Little League of Virginia Beach in the early 1960s.

Thomas was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. He was reported to have been a veteran of World War II, despite being sixteen at war’s end.

Over the years, Thomas occasionally sent letters to the editors of his local newspapers. On one occasion, the “Letters to the Editor” section of the April 9, 1953, edition of the Richmond News Leader newspaper carried the following heading: “Of Hillbilly Music: Defenders Cite Its Background, Like Its Future.” Newton Thomas (then twenty-four) was one of several contributors. In his letter, he described himself as “having been a musician all my life.” While professing a “lack of knowledge on the subject” of hillbilly music, he added with authority that “I do know American jazz.”

Having made such an admission, it was somewhat of an oddity that the November 14, 1953, edition of Billboard magazine reported that “Newton Thomas Jr. [is] airing two and a half hours of country music daily at WXGI, Richmond, Va.”

Thomas was either being modest when he professed a lack of knowledge on hillbilly music, or he was a quick study. In slightly more than a month’s time, three mainstream country artists recorded songs on major labels that he had written: Roy Acuff recorded “Rushing Around” for Capitol on December 2, 1953; Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper recorded “Brand New Baby” for Columbia on December 28, 1953; and Smilin’ Eddie Hill recorded “Who Wrote That Letter to Old John” for RCA Victor on January 12, 1954.

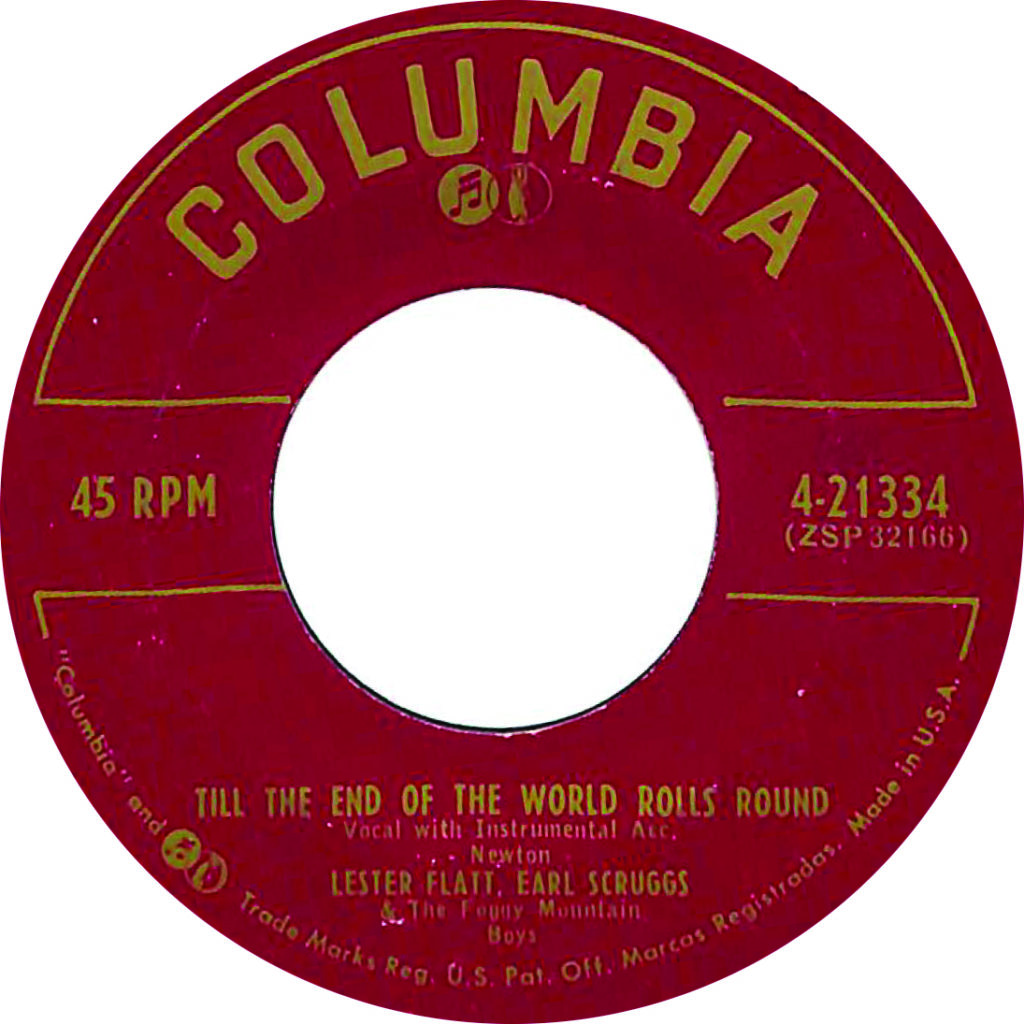

It was only a short time later that “Till the End of the World Rolls Around” was first recorded – but not by Flatt & Scruggs. A Knoxville-based duo known as the Webster Brothers, Earl and Audie, recorded the song on March 24, 1954, at a session for Columbia Records. The duo had been recently signed to the label by producer Don Law and song plugger Troy Martin (see “Notes and Queries,” February 2023). It was no coincidence that Martin represented the song’s publisher, Driftwood Music Co. The recording by the Webster Brothers was released six months later, in October 1954.

The song was finally recorded by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs on May 19, 1954. It was the lead song at a four-song session for Columbia Records. It was the group’s first session to feature their new fiddler, Paul Warren. “Till the End of the World Rolls Around” was also the first song to feature Earl’s use of new “Scruggs tuners” on the banjo. The Flatt & Scruggs recording trailed the Webster Brothers release by one month and appeared on the market on November 22, 1954.

Thomas related once that the song was “written on a bet” and was sent to a publisher in Nashville. He added that Lester Flatt overheard the song while visiting the publisher’s office and agreed to record it on the spot.

Thomas’ last coup as a songwriter came in the middle part of 1954 when Chapel Hill-based Colonial Records inked a deal to record legendary baseball pitcher Dizzy Dean. The label was riding high from the previous year’s “What it Was, Was Football” by up-and-coming Andy Griffith. On August 27, 1954, Dean recorded “Wabash Cannonball,” as a tribute to his longtime friend Roy Acuff, and the Newton Thomas song “You Don’t Have to Be From the Country (To Like the Music of a Good Hillbilly Band).” While “Wabash Cannonball” was clearly chosen as the A side of the disc, “You Don’t Have to Be From the Country” benefitted from nation-wide exposure, including a full-page ad in Billboard magazine. While the Dean name carried a lot of notoriety, reviews of his talents as a recording artist were tepid, at best.

Colonial owner Orville B. Campbell also owned the publishing firm that copyrighted “You Don’t Have to Be From the Country,” Bentley Music. Wishing to further exploit the song, in the very early part of 1955, he arranged for a regional group, Hack Johnson and His Tennesseans, to record the song for Colonial. With lead vocals by Johnson, the track benefited greatly from hot banjo picking and fiddling by Allen Shelton and Roy Russell. As with the Dean release, it was the flip side of the record – Allen Shelton’s masterful banjo-driven interpretation of “Home Sweet Home” – that garnered the most attention.

Having two of his songs on the market at the same time, the April 30, 1955, edition of Cash Box reported that “Newton Thomas [was] into Nashville recently enroute promoting latest Hack Johnson (Colonial) and Lester Flatt-Earl Scruggs (Columbia) latest wax.”

For whatever reason, Thomas seemingly laid down his pen and had no further activity as a published author of songs for the country music market. He continued performing around the Richmond area with his jazz trio and was still heard as a country disc jockey on WXGI. In 1958, he moved to WPVA in nearby Petersburg, Virginia. In 1960, he was one of six Richmonders who passed the real estate test to become a broker.

Thomas moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1968. For many years, he fronted a swing band called Vintage and for thirteen years operated a retail establishment Newton Thomas Music.

Lee Moore & the Shady Valley Boys

Matthew Madden supplied a photo of what he described as a “Country/Western Band from Staunton, Virginia from the early 1940s.” He came into possession of the photo by answering a classified advertisement and added that “the lady has a pre-war Martin D-45, although it looks to me like snowflake inlays. And the guy beside her has a pre-war Gibson J-35.”

The photo actually dates from late 1944 or early 1945. It features Lee Moore and the Shady Valley Gang, popular entertainers on radio station WSVA in Harrisonburg, Virginia. From left to right are Bill Franklin, Lee Moore, Juanita Moore, and a guitar player identified only as “Little Willie.” At front and center is four-year-old Roger Lee Moore.

The group was headed by Walter Leroy “Lee” Moore (September 24, 1914 – August 17, 1997), a native of Circleville, Ohio, who later gained fame as a night time disc jockey – the Coffee Drinkin’ Night Hawk – over radio WWVA in Wheeling, West Virginia. He began performing in public in his late teens, shortly before graduating from high school.

Throughout the early and middle 1930s, Lee worked as a solo or in other bands. In 1937, he found himself broadcasting over radio station WCMI in Ashland, Kentucky. It was while in Ashland that he met Juanita Picklesimer (March 15, 1917 – March 23, 2008), a radio performer who was sometimes billed as the “Girl From the Hills of Ole Kentucky.” The following year, 1938, the couple were reunited when they both worked at WCHS in Charleston, West Virginia. They married a short time later.

Lee and Juanita often performed as a duet. The act also included some solos by Lee. A third member appeared in mid-1940 when Roger Lee Moore (May 1, 1940 – March 22, 2022) was born. As soon as he was able, he became a featured part of the act, and earned the title of “Radio’s Youngest Hillbilly Star.”

With the advent of World War II, the Moores alternated between WMMN in Fairmont, West Virginia, and WSVA. By the early part of 1943, the group included Lee and Juanita, Curly Joe from Ole Mexico, Buck the Accordion Man, Shorty and Toby, Bob Autry, and Little Roger Lee.

It was an advertisement for Lee Moore and the Shady Valley Gang at the Visulite Theatre in Staunton, Virginia, on February 16, 1945, that helped to date Matthew Madden’s photo. It listed everyone who appears in the photo: Bill Franklin (WSVA Sensational Singing Star), Lee Moore, Juanita, Little Willie, and Roger Lee.

The same advertisement also said that Bill Franklin would soon be leaving the group. Bill Carroll Franklin (sometimes listed as Billie or Billy) (February 29, 1928 – October 16, 2007) was a West Virginia native who, with his brothers Clyde and Delmas, was part of a family group known as the Franklin Brothers. While they were popular as radio entertainers, they made few (if any) published recordings. One acetate featuring the group singing “Sweeter Than the Flowers” appeared on a Rounder Records Early Days of Bluegrass album in the middle 1970s. Bill Franklin’s claim to fame as a songwriter was “That Moon’s No Stopping Place For Me,” as recorded by Reno & Smiley in the early 1960s.

Over Jordan

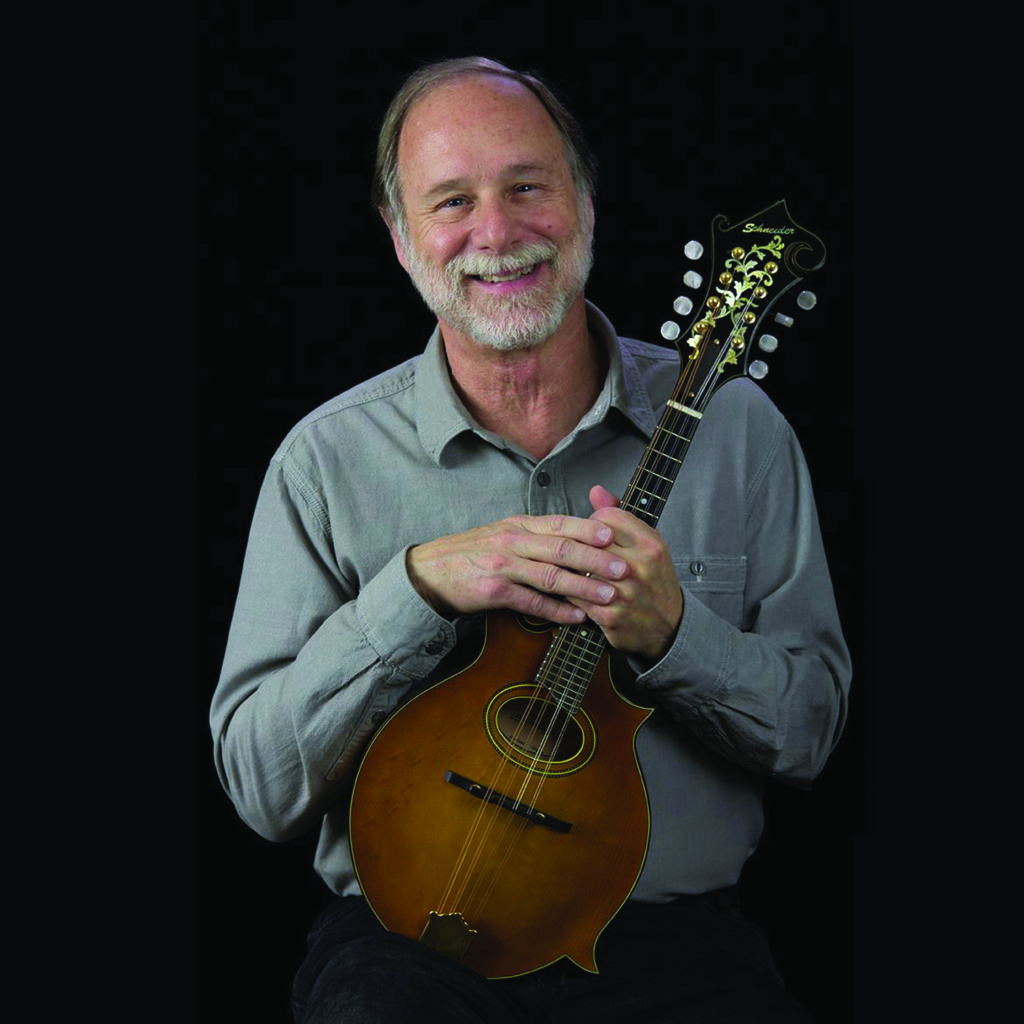

Dix E. Bruce (September 10, 1952 – February 1, 2023) was a California-based multi-instrumentalist who is revered as much for his musical virtuosity as for his voluminous output of performance instructional materials. Known primarily for his work on guitar, banjo, and mandolin, he was conversant on a number of genres of music, including bluegrass, jazz, Americana, folk, and rock. As an educator, he authored/assembled over sixty instructional books, videos, and compact discs. As a performer, he had more than a dozen releases.

Although he resided in California for over fifty years, Dix was a native of Madison, Wisconsin. It was there he had his first exposure to music. As a youngster drifting off to sleep, the sounds of his grandfather’s D-21 Martin guitar wafted through heating ducts into his room. Soon, Dix learned to use his thumb to strum out rhythms on the guitar. Later, he discovered the music of Clarence White and the Kentucky Colonels. In college he beefed up his interest in bluegrass by attending performances by Doc and Merle Watson, Ralph Stanley (with Roy Lee Centers, Ricky Skaggs, and Keith Whitley), and the regional Monroe Doctrine. During the same timeframe, Dix began learning some Carter Family-style leads on the guitar.

Shortly after graduating from college in 1974, Dix headed west to California. There, he secured a job teaching at a local music store. Attendance at a concert by Frank Wakefield led to performance and recording opportunities with the mandolin guru. Dix’s dive into the mandolin got a further boost when Darol Anger introduced him to David Grisman. It was only a short time later that Grisman tapped Dix to assume the editorship of his quarterly publication Mandolin World News. Interviews, with the opportunity to “talk shop,” with heavy hitters such as Bill Monroe and Jethro Burns soon followed.

In the late 1970s, Dix joined the California band Back Up and Push. He also started writing instructional books for Mel Bay Publications. In time, he authored more than fifty books for the firm.

When an earthquake put a temporary hold on live performance opportunities, Dix took a job with Arhoolie Records. He did engineering and songwriting work (including music for the label’s popular Sims City computer games) and also used his computer skills to edit and layout CD booklets, design covers, and occasionally write notes. He stayed with the firm until 1997.

In the middle 1980s, Dix became aware of guitarist Jim Nunally. Eventually, the two hooked up and became musical partners for many years. They toured and released at least four projects together, the first of which was the critically acclaimed 1995 disc From Fathers to Sons, a collection of traditional songs and tunes that Jim and Dix learned from their early musical mentors.

Among Dix’s other career highlights were his twenty-year tenure as a contributor to Acoustic Guitar magazine, his founding of his own music instruction company called Musix, his recording and release of an album of old-time and traditional material with Frank Wakefield called My Folk Heart, his teaching at numerous musical instruction camps, his service (with Jim Nunally) as a Martin Guitar clinician, and his writing and release of his Parking Lot Picker’s Songbook.

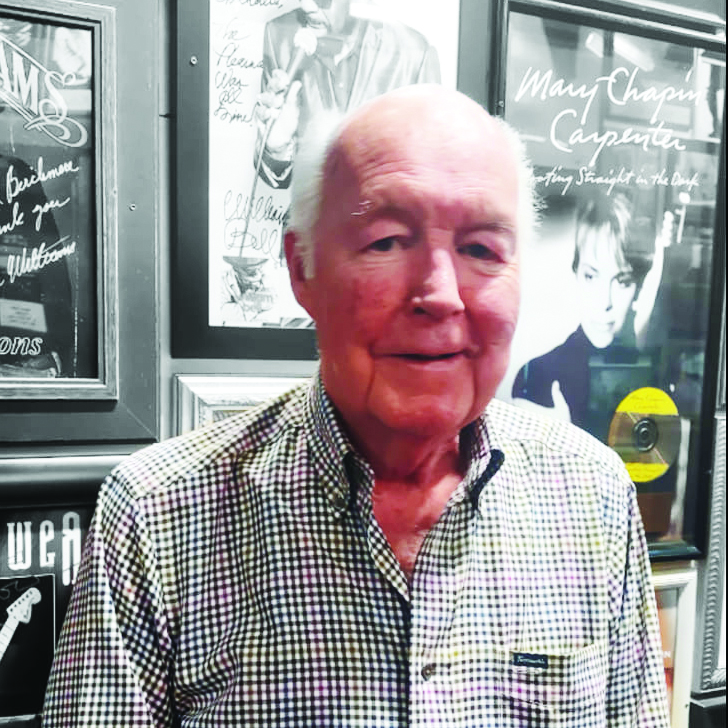

Gary Hagan Oelze (August 24, 1942 – January 23, 2023) was the founder and long-time proprietor of the Birchmere, one of the premiere venues for the presentation of bluegrass, Americana, and related forms of music.

A native of Owensboro, Kentucky, Oelze’s journey from there to his role as the overseer of the trendy Northern Virginia nightspot was a circuitous one. In the early 1960s, he served a four-year hitch in the Air Force. His most recent assignment landed him in the Washington, D.C., area, where he remained after his discharge. For the next several years, he found employment in a drugstore chain in the D.C. area.

It was Oelze’s management style at the drugstore that prompted a co-worker to lure him away to manage a restaurant. It opened in 1966 as the Birchmere, its name being derived from a youth camp that the owner had attended. While the restaurant enjoyed a brisk day-time lunch business, evenings were slow. To remedy the situation, Oelze decided to book bands as a draw. In addition to area bluegrass bands, the roster of early talent included his own group (he learned to play guitar around age fifteen).

While he was not a hardcore bluegrass fan, Oelze was familiar with the genre and felt that, as an art form, the music deserved better than some of the rough and tumble bars of the D.C. area. Taking his cues from Georgetown’s The Cellar Door, he placed signs on each table that requested silence from the audience during performances. He also invested in a state-of-the-art sound system which he himself operated for a number of years.

Music fans from outside the D.C. area began to take note of the Birchmere when groups such as Boone Creek and the Seldom Scene called the venue home base. In fact, the Scene had a standing Thursday night gig at the club for nearly twenty years. And, one never knew what sort of surprises awaited . . . such as the time Bill Monroe dropped in unannounced for an impromptu 45-minute set. And there were surprises in the audience, too . . . like the visits from President Bill Clinton and Vice Present Al Gore.

Over the life of the Birchmere, Oelze operated the club out of three different locations, each one increasing in seating capacity. The most recent location had a capacity for five hundred patrons as well as a separate dance hall with a seated bar. Believing that a relaxed and well-rested entertainer performed better than one that wasn’t, Oelze strove to make a music-makers experience at the Birchmere as comfortable as possible. This included, among other amenities, the addition of showers and washers and dryers for road-weary travelers.

Many attributed the Birchmere’s success to Oleze’s mantra of always doing things “the right way.” This included his reverence for the music and the listening-room atmosphere he created. It also extended to the friendships he developed with performers and attendees alike. Oleze was unique among promoters and talent buyers of his day. He left a legacy that others will no doubt aspire to emulate.