Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – 2025

Notes & Queries – 2025

Fiddling Gopher Addis (or, More on Don Reno Sidemen)

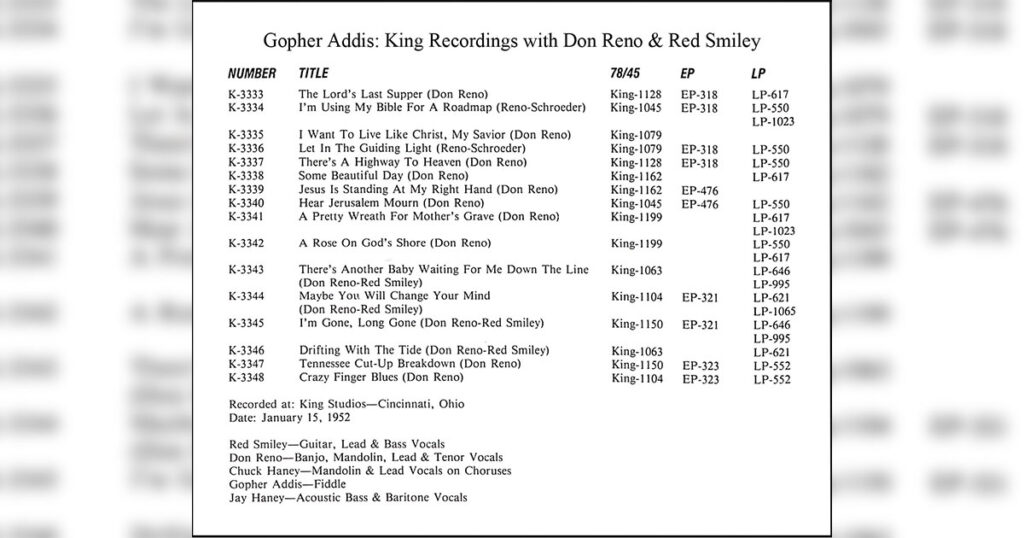

In last month’s column, we fielded a query concerning two musicians who worked with Don Reno and Red Smiley in the early 1950s: Chuck and Jay Haney. The Haneys had the distinction of appearing on Reno & Smiley’s first recording session together, on January 15, 1952 (see sidebar). What wasn’t asked about, but which should have been discussed, was the identity of the fifth member of that historic recording session, a fiddler who was known only as Gopher Addis.

Addis was born during the depths of the Great Depression on July 13, 1933. As with several other bluegrass musicians who were born during the Depression (notably Franklin Delano “Frank” Wakefield and Delano Floyd “Del” McCoury) Franklin Delano “Gopher” Addis was named after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Gopher was never comfortable with the name and during his formative and teen years was known to friends and family as F. D. He later acquired the nickname of “Gopher” because, as he told his nephew Mark Kerr, he would “go for anything.” Some alternate spellings appeared as “Gofer.”

Gopher hailed from the South Carolina cotton mill town of Jonesville. Although there was a piano in the Addis household, the family wasn’t necessarily musical. Gopher played around some on the piano but what really captured his imagination was the fiddle, an instrument that he acquired at age 13. He never took any lessons but rather was self-taught. Gopher’s sister recalled recently that he practiced all the time. People who knew of him in and around the Jonesville area thought of him as a natural born talent.

Shortly after Gopher acquired his fiddle, his older brother Cedric (“Sed”) picked up the guitar and the two made music together, and also with several others from their community. Eventually they formed a group called the Melody Boys and had an early morning radio program over WSPA in Spartanburg, South Carolina; they also served as an opening act for the regionally popular Blue Ridge Quartet. At one point, there was an offer from a nationally touring band for Gopher to go on the road, but, being a young teenager, he declined.

Closer to home, Gopher was a member of two influential country music groups: Don Gibson & His King Cotton Folks and Don Reno, Red Smiley & the Tennessee Cut-Ups. He started with Gibson first, appearing with him on Knoxville’s Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round. Other band members included his brother Sed on guitar, Summie Hendricks on steel guitar, and Bill Kirby on bass. Gopher’s first stint with Gibson was cut short when he was called home to complete his senior year of high school; he returned to Gibson shortly after graduation.

Don Reno & Red Smiley organized the Tennessee Cut-Ups in about September of 1951. Gopher stayed with the band long enough to appear, at age 18, on that group’s debut session for King Records. While at King Records, the Reno & Smiley troupe (including Gopher) was recruited to play on four songs by songwriter Mac Odell: “Let’s Pray,” “Be On Time,” “When the Hand of God Comes Down,” and “Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing.” As with the Reno & Smiley session, Gopher played fiddle on the Odell session.

Due to a lack of work, Reno & Smiley dissolved their group shortly after their recording session. This left Addis free for work with other groups. One such outfit was Claude Casey and His Sage Dusters which had a regular program on WFBC in Greenville, South Carolina. He also reportedly worked with country singer Skeeter Davis.

Addis was involved in a serious automobile accident at some point in the late 1950s. Whether it was by coincidence or because of it, after the accident Gopher limited his playing to local engagements with regional groups. Some of the bands he performed with were the Rolling River Band, The Carolinians, and The Overalls. It was with the last-named group that Gopher helped to record an 8-track tape.

For all his natural talent, Gopher Addis has, until now, been known only as a footnote in bluegrass history. But bluegrass was only one part of his story. He was also a fan and performer of country music and western swing. Those who knew him often wondered why he didn’t take his talent to the next level. As has been the plight of other creative musicians, alcohol was a contributing factor. Gopher spent the last 20 years of his life living with his parents in the house in Jonesville where he was born. It was there, sadly, that he died of a heart attack on March 11, 1992; he was 58.

Over Jordan

Marshall Jacob Brickman (August 25, 1939 – November 29, 2024) was cited by author Richard D. Smith recently as “a brilliant banjo player.” His crowning achievement on the 5-string was a 1963 album, in collaboration with fellow banjoist Eric Weissberg, called New Dimensions in Banjo and Bluegrass. It was the first bluegrass album to feature the then-emerging chromatic style of banjo playing. It was his one and only bluegrass album recording.

Brickman emerged from very un-bluegrass-like surroundings. He was born in Brazil to a Polish-born father and American-born mother. He spent his formative years in Brooklyn where his father, Abram, worked as an importer/exporter. Marshall’s mother, Pauline, was, among other things, an accomplished pianist and, when he was five years old, she began teaching him classical piano. His journey with the banjo began at age 10 (ca. 1949).

During the 1950s, Brickman was part of a throng of musicians who gathered every Sunday at Washington Square Park in New York’s Greenwich Village. In 1980, he told interviewer Claudia Dreifus that “playing the banjo was the one social escape that I had. A lot of things were proscribed to me by my upbringing. But the banjo and music were permitted. I would go to Washington Square on Sundays. It was a way of meeting girls and being cool. Girls with leather belts and leotards would come up to me and notice me.”

In 1956, he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin and eventually graduated with bachelor degrees in science and music. At school, he made music with fellow student Eric Weissberg and served as an inspiration to other aspiring pickers. John Herald, later a founding member of the Greenbriar Boys, recalled that “I followed them around campus like a puppy.” It was also while at Wisconsin, in the summer of 1957, that Brickman traveled to Moscow to attend the World Youth Festival. He won a gold medal at the event, playing “Earl’s Breakdown” on the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre as part of the international folksong contest.

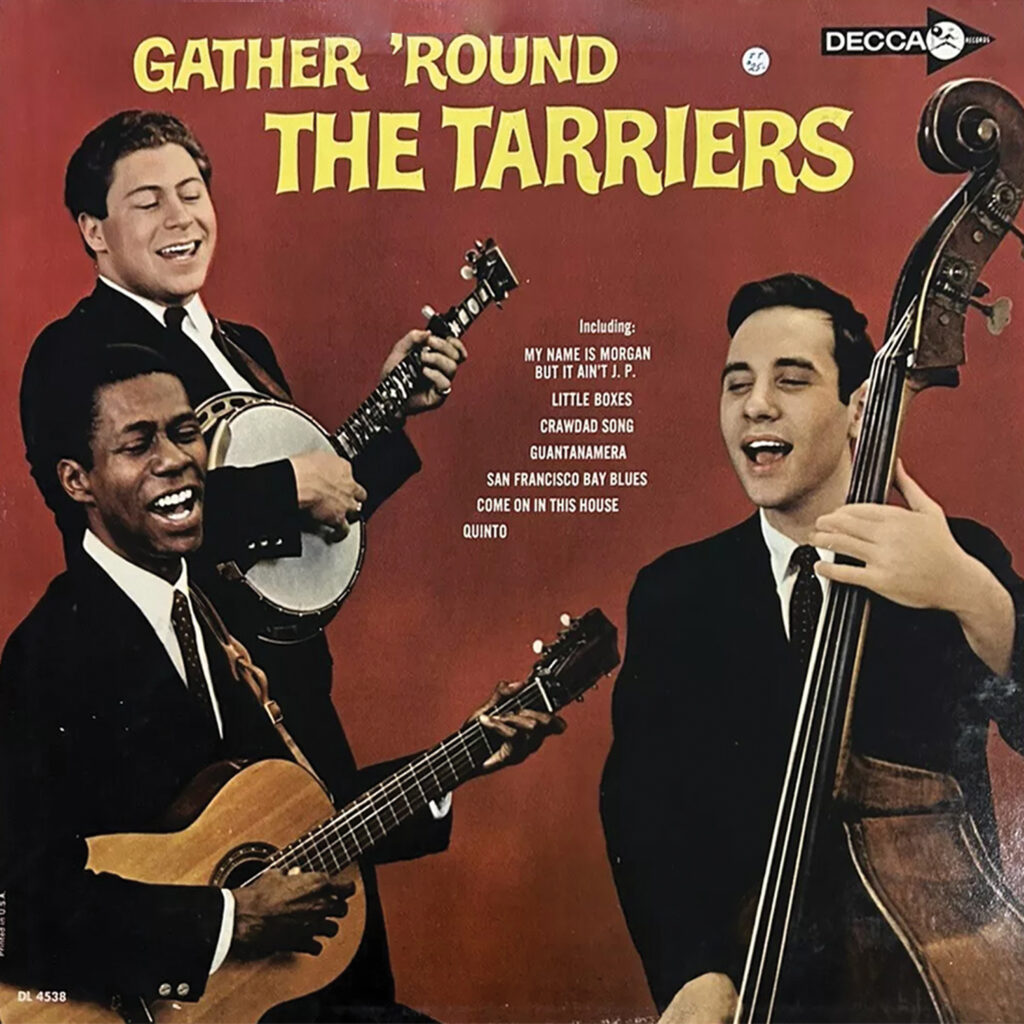

Following graduation from the University of Wisconsin, Brickman applied to, and was accepted by, The Juilliard School. However, competing opportunities took precedence. First was a 1961 partnership with Dan Kalb; the duo sported a varied program that included performances on banjo, guitar, mandolin, and fiddle. Second was an invitation to join the folk group The Tarriers, which included pal Eric Weissberg. As Weissberg handled the banjo chores, Brickman played bass, guitar, fiddle, and mandolin. And, as he was able to tune his instrument faster than any of his band members, he became the de facto master of ceremonies for the group.

Brickman stayed with The Tarriers for several years in the early to mid-1960s. During that time, he recorded three albums with the group. On one of the albums, Folk Songs for Fun, the group acted as a back-up band for folk singer Oscar Brand. Another gave a taste of the group in concert: A Live Performance Recorded At The Bitter End, Greenwich Village, New York City. One song on that album, “Children Go Where I Send Thee,” became a staple of Ralph Stanley’s shows a decade later. Last was a 1964 disc called Gather ‘Round the Tarriers; it featured a blistering banjo/mandolin workout on Bill Monroe’s “Rawhide.”

While The Tarriers were primarily a folk group, touring with the outfit did have bluegrass benefits. One of the biggest payoffs was the opportunity to see the duo of Jim Rooney and Bill Keith in action at the Club 47 in Boston. In a Bluegrass Unlimited article by Tony Trischka, Keith recalled that “both of them (Brickman and Weissberg) were in town with the Tarriers and they came into the Club 47 where Jim and I were playing. We played our medley, our big instrumental, I think we played it once a set at that point, and they heard it and looked at each other and then a couple of months later they had their record out.” The tune in question was Keith’s chromatic banjo showpiece “Devil’s Dream.”

Again, it was touring with The Tarriers, in 1963, that put Brickman in touch with West Coast record producer Jim Dickson; he served as the producer of the Brickman-Weissberg album New Dimensions in Banjo and Bluegrass. It contained their take on “Devil’s Dream.” The album was likely recorded shortly after The Tarriers’ February 19, 1963, appearance at The Ash Grove coffeehouse in Hollywood where the Kentucky Colonels (with guitarist Clarence White) held forth; White and country fiddler Gordon Terry appeared as guest musicians on New Dimensions. The release of the album was first mentioned in the September 14, 1963, edition of Billboard magazine.

In assessing their work, Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Frank Godbey noted that “Weissberg and Brickman were basically instrumentalists who were primarily interested in complete freedom of expression on the 5-string banjo, maintaining access to traditional forms but by no means being confined by them. Accordingly, they experimented with long complex runs, unexpected chord changes and unusual phrasings. In addition, they applied what they had learned to intricate double banjo arrangements of several tunes, most notably ‘Reuben.’ They brought these ideas to the general public with the release of their album, thereby becoming the first to record in the [chromatic] style that has since captured the fancy of countless banjo enthusiasts. ‘Shuckin’ the Corn,’ played by Marshall Brickman, provides an effective illustration of the differences between Scruggs’ style and chromatic; and further comparison can be found in ‘Earl’s Breakdown.’ ‘Black Rock Turnpike’ was another outstanding example of chromatic banjo wizardry. The remaining pieces offer both traditional and chromatic licks in a variety of combinations and sequences.”

Brickman was later quoted as saying that the New Dimensions album sold 5,000 copies. Nearly a decade later, the album (minus two tracks that were replaced with two newly recorded tunes: “Dueling Banjos” and “End of the Dream”) was chosen as the soundtrack to the hit film Deliverance. Brickman related that that album sold 1,200,000 copies. His lawyer presented him with a check for $78,000.00 and told him there would be three or four more.

By the time of the release of the Deliverance soundtrack, Brickman had retired from life as a road musician. Again, speaking with Claudia Dreifus, he noted that “eventually, being a Tarrier depressed me. I had some terrible premonition that I might become a 40-year-old beatnik if I stayed with it too long . . . I wanted to do different things-writing.” And write he did, for television shows such as Candid Camera (a 1960s precursor to America’s Funniest Home Videos) and for talk show hosts Dick Cavett and Johnny Carson. Then there were screenplay co-writes with film director Woody Allen such as Sleeper, Annie Hall, and Manhattan. He also wrote and directed a sci-fi comedy called Simon. Perhaps his biggest success was the musical Jersey Boys, which ran on Broadway from 2005 to 2017.

Lonnie George Hoppers (July 25, 1935 – November 17, 2024) was a banjo player from Missouri who was known for a short-lived stint as a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. While that job rates as his most high-profile gig, it was but a small part of a career that ran from the 1950s until well into the 2000s.

Hoppers was a native of Urbana, Missouri, where his father George operated a blacksmith and machine shop. He developed an interest in the five-string banjo at age 14. Shortly after graduating from high school in 1953, Hoppers joined with Bob McCoy and Bob Perry to form the Ozark Mountaineers. The following year, the troupe launched the Ozark Opry. The program was intended as an entertainment to stimulate tourism in the region. Hoppers played banjo with the show through the middle part of 1958. Towards the end of his tenure with the group (ca. 1957), Hoppers received, but declined, an invitation to join Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys.

Monroe had used Lonnie as a fill-in back in 1957 and offered the banjoist a spot in his band. However, the steady work offered by the Ozark Opry, coupled with the fact that he was then dating his future wife (Charlene Carson), caused Hoppers to decline; the couple married two years later on September 16, 1959. Monroe wasn’t the only one paying attention to Lonnie’s banjo work; Doug Dillard and Dale Sledd both cited Lonnie as influencing their development as musicians.

From 1958 through 1961, Hoppers served in the United States Army. While stationed at bases in Missouri and Kentucky, Hoppers found opportunities to make music. His proximity to Nashville allowed him to make frequent trips to the Grand Ole Opry. A second invitation to join Monroe had to be declined due to an extension of Hoppers’s military service.

Once out of the military, Hoppers settled in Kansas City, Missouri and secured a day job with Western Electric. In August 1961, he landed a spot with the newly formed Ozark Mountain Boys. He continued to play locally until September of 1962 when he finally accepted an offer from Bill Monroe. His tenure as a Blue Grass Boy was brief, and ended in January 1963. He cited the low pay and scarcity of jobs for his decision to leave.

Although brief, Hoppers’s stay with Monroe was productive. He often performed on the Friday Night Opry and the Saturday evening Grand Ole Opry. He also participated in four recording sessions which yielded a total of twelve songs and tunes: “Careless Love,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “Jimmy Brown the Newsboy,” “Pass Me Not,” “The Glory Land Way,” “Farther Along,” “Big Sandy River,” “Baker’s Breakdown,” “Darling Corey,” “Cindy,” “Master Builder,” and “Let Me Rest at the End of My Journey.” Bandmates on the recordings included Kenny Baker, Joe Stuart, and Bessie Lee Mauldin.

Working with Monroe offered Hoppers the opportunity to see firsthand some of the other first generation bluegrass bands. “When I was a Blue Grass Boy, we played a few shows that Ralph and Carter Stanley were also on. The main gig I’ll always remember is when we played a New Year’s Eve dance in Luray, Virginia. Just the Blue Grass Boys and the Stanleys, December 31st 1962. There were a couple of indoor festivals around that time, put on by Carlton Haney. One was in Richmond, Virginia, and another in Roanoke on New Year’s Day, 1963. We played a couple other shows with Ralph and Carter. We all stayed at the same motel one night and when we left the next morning, headed for another show date, Bill asked Carter to drive his old 1959 Olds wagon and told me to ride with Ralph. That shows how much Bill thought of Carter. He trusted Carter to drive (Bill never drove on the road) and he wanted to visit with Carter!”

After leaving Monroe, Hoppers returned to Kansas City and resumed work at Western Electric. On weekends, he performed with friends at area coffee houses. These informal picking sessions put him in touch with guitarist/Kansas City native Dan Crary. The two developed a friendship that later blossomed into several band situations, including National Grass Ltd. in the early 1970s. When Crary headed west in the middle 1970s, Hoppers performed with The Green Side Up.

In 1978, as Hoppers’s daughter was completing high school, Lonnie accepted a position at the Silver Dollar City theme park in Branson, Missouri. There, he played banjo five days a week with the Horse Creek Band. While there, he released his one and only solo album, Pickin’ For Fun. After several years (ca. 1982) at the park, Hoppers was appointed Director of Music for the facility. One of the musical highlights from this era was a summer season that included picking five days a week with the Dillards.

He also performed at other Branson theatres and the Shepherd of the Hills outdoor theatre. Lonnie also performed for movies and TV shows that were made in Branson.

In 1985, Hoppers hooked up with the Plummer Family Show. With it, he alternated between playing banjo and electric bass. The troupe spent the tourist season in and around the Branson area and toured during the off seasons. He stayed with the group thru the end of the 1980s.

The middle 1990s saw the formation of a new group, Lonnie Hoppers & New Union. His wife, Charlene, played guitar and sang. The pair also hosted bluegrass radio programs on KYOO in Bolivar, Missouri, and KBFL in Buffalo, Missouri.

A 1998 performance in Guthrie, Oklahoma, reunited Hoppers with Dan Crary. The two played on stage after an absence of too many years. Energized by their chemistry together, the duo went in the studio to record a new CD and booked a number of shows for the 2000 festival season. Their disc on the Pinecastle label was called Crary & Hoppers and Their American Band.

In the early 2000s, Lonnie enjoyed two tours of Australia and on June 10, 2002, he was commissioned a Kentucky Colonel.

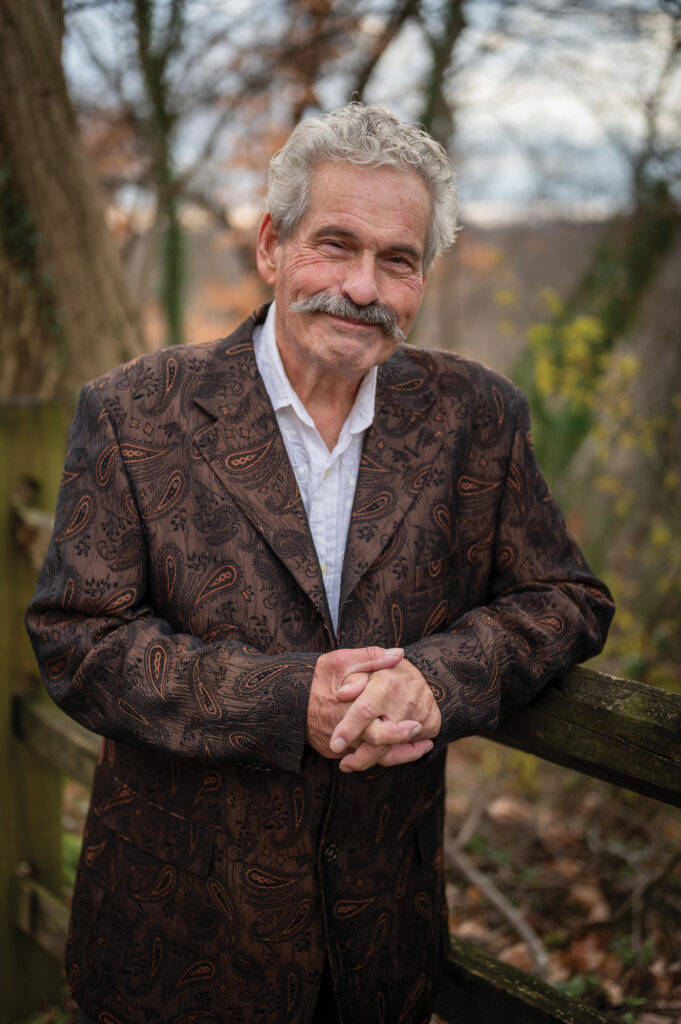

Frank Robert “Bob” Perilla III (June 26, 1953 – December 12, 2024) was a mainstay of the Washington, DC bluegrass scene and is best-known for fronting the group known as Big Hillbilly Bluegrass. A native of Woodbine, Maryland, a tiny community located within the triangle of Washington, Baltimore, and Frederick, Maryland, he hailed from a non-musical family. His discovery of bluegrass came from the radio where DJs such as Ray Davis from Baltimore’s WBMD played the music. Perilla’s early attempts at playing music centered, first, around the banjo and, later, the drums. Eventually the guitar became his instrument of choice; his forceful rhythm style was compared to heavy-hitters such as Jimmy Martin.

Following graduation from Georgetown University, Perilla spent a decade in corporate America as a salesman for Monarch Rubber (1980-1990) and, concurrently, as a Market Development Director with Uniroyal (1985-1990). Still, in 1987, Perilla told the Baltimore Sun that “I can’t visualize not pursuing music.” After having apprenticed under local legends such as Buzz Busby and Don Stover, the late 1980s/early 1990s found Perilla performing in several groups, including Baltimore’s Satyr Hill Bluegrass Band and Jackstraw.

In the mid-1990s, Perilla teamed up with mandolin picker Tom Mindte. At their recurring gig at Washington’s Madam’s Organ, they were (due to their portly nature at the time) billed as Big Hillbilly Bluegrass. The name stuck. A rotating cast of characters (including Mike Munford, Tad Marks, Akira Otsuka, Jon Glik, Ira Gitlin, Dick Smith, Norman Wright, and Kevin Church) came and went but Perilla remained as the unifying focus of the group. The gig started in 1996 and ran for the next 14 years. Frommer’s travel guide listed the venue as having “great music and sweaty people.” Clientele was a mix of rank-and-file bluegrassers, Capitol Hill staffers, diplomats, and tourists.

In addition to leading Big Hillbilly Bluegrass, Perilla served as the manager of Appalachian Bluegrass, a music store in Catonsville, Maryland. His knowledge of the music made him an ideal salesperson for the store. And, when he wasn’t selling, he could be found sitting in on impromptu jam sessions that took place there.

The early 2000s were the most productive years of Perilla’s career in music. There were high profile performances at the Kennedy Center and the Smithsonian Institution’s Folklife Festival. In 2003, he and the band were featured, briefly, in a Chris Rock film called Head of State. The group was collectively credited for the song “Head of State” that was featured in the movie. In 2005, Perilla released his only studio album, which was called, quite naturally, Bob Perilla’s Big Hillbilly Bluegrass. That same year, the band was tapped for the first of several overseas tours that were sponsored by the State Department. As bluegrass ambassadors, the group represented the United States in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Central African Republic, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Republic of Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Mauritania, Moldova, Republic of Congo, Sultanate of Oman, Tajikistan, Togo, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.

Following the end of the gig at Madam’s Organ, Perilla continued to maintain a presence in the Washington area with performances at various nightspots. He also wrestled with several health and medical issues that included a kidney transplant and injuries that were sustained in a motorcycle accident. Perilla was possessed of an upbeat and outgoing personality and left a positive mark on all those with whom he came in contact.