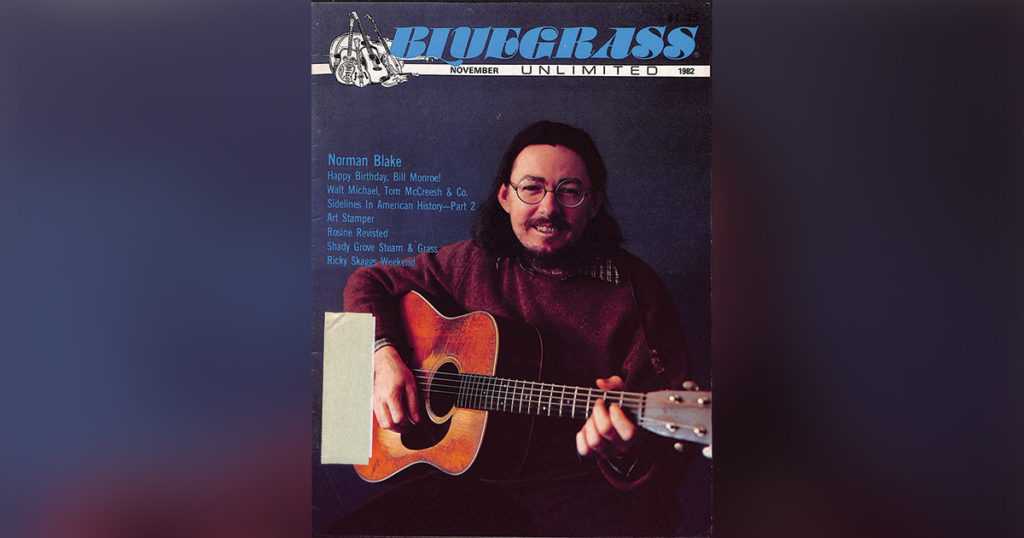

Home > Articles > The Archives > Norman Blake

Norman Blake

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1982, Volume 17, Number 5

Norman Blake is as close to being a “star” as a musician can get in the field of old-time acoustic music. With the aid of a single-minded sense of where he wanted his music to go; and of dedicated hard work that would satisfy any worshiper of America’s work ethic, Blake’s career has progressed steadily since his days of performing for radio programs throughout the south with the Dixie Drifters in the 1950s.

The bespectacled guitarist first garnered respect as a Nashville session man in the 1960s. Toward the end of that decade, he started hooking up with big names like Johnny Cash, for whom he played guitar and Dobro on Cash’s network television show, and Bob Dylan, whom he accompanied on the “Nashville Skyline” LP. Soon after he toured and recorded with Kris Kristofferson and Joan Baez. In addition, he contributed some graceful guitar and mandolin to John Hartford’s droll paean to the good ole days —“Aereoplane” —in 1971.

Since then Blake has come up with a steady stream of solo albums for three of the biggest independent labels — Rounder, Takoma and Flying Fish. He is currently under contract with Rounder for what was one of the first long-term, multi-album deals ever offered to an acoustic, folk-oriented musician on an independent label.

Norman Blake’s music was among the first old style acoustic music this young writer —who missed out on the traditional music “revival” of the sixties—ever heard. I’ll never forget hearing my friend’s copy of “Home in Sulphur Springs” for the first time. Blake’s tasteful approach didn’t just follow the southern Appalachian tradition. It continued it. Sure, the old-time songs like “Little Joe” and the traditional fiddle tunes sounded pure and honest. But even more amazing was the fact that Blake’s own compositions (“Down Home Summertime Blues,” “Randall Collins” and “Crossing No. 9” among others) also sounded like they had been unearthed from ancient deposits of the red Georgia soil he grew up on.

The soft-spoken southerner has not changed his approach to making albums since “Home in Sulphur Springs.” All of his records feature spare, unembellished arrangements of a similar mix of traditional and original material as that on “… Sulphur Springs.” The Rounder releases “. . . Sulphur Springs,” “Whiskey Before Breakfast” and the two albums with the Rising Fawn String Ensemble —are recommended slightly above the Flying Fish and Takoma records as the best Blake albums to own.

The 44-year-old picker (he was born March 10, 1938) spoke enthusiastically about his latest recording projects during his most recent tour of the West Coast. A reclusive musician who seems to question the value of the music press, Blake nevertheless provided some insight into just why he has become such an important contributor to today’s southern music.

“I’ve been working on two projects in the studio lately,” he said. “One is a mandolin album that I’ve always wanted to do. It’s got a lot of different arrangements on it, sometimes just solo mandolin, sometimes mandolin- mandocello and some of it is mandolin-mandolin. The other is more of a mix of styles. I’m not sure which will come out first.”

According to Marian Leighton at Rounder, the mandolin record will appear first. “It’s called “Original Underground Music From the Mysterious South,” Leighton said. “It will be released in the early fall. Its Rounder catalog number is 0166.” She also said that the other project Blake talked about “is already in the can. It’ll come out sometime next year, probably around a year from the time this mandolin record comes out. It depends on Norman’s touring plans and also it depends on when he wants it to be released.” Since Blake is best known as a guitarist, the new record may turn some heads as people discover he is a wizard on the mandolin as well.

The new album will be Blake’s third release for Rounder since signing his current contract. Both parties are pleased with the artist-label relationship. Leighton said Rounder has consistently been satisfied with the musician’s album sales.

Blake worked his way to commenting on Rounder by speaking of independent labels in general. “One advantage of recording for an independent label is I was able to get a big, multiple album contract,” he commented. “On the big labels, they’ll put their money out for you on one record, but if it doesn’t sell they’ll drop you immediately.” And how often does a traditional-sounding acoustic musician sell enough records to satisfy the blockbuster-demanding appetites of the major labels?

“On an independent label,” the Georgian continued, “they’ll give you full artistic control. I like the idea of not having to answer to anyone.” Making records for the small labels is accordant with the musician’s personality, which is as fiercely independent as the record companies he has been associated with. However, Blake admits that the big companies could do a lot for the exposure of old-time country and bluegrass music, “but only if they’d accept it for what it is.”

In comparing the small labels of his recording career —none of which are really all that small anymore —Blake asserted that there are major differences between Takoma, Flying Fish and Rounder. “I had good relations with Flying Fish,” he said of the Chicago company, “but Rounder is able to back up my stuff more. That’s the main thing that makes Rounder different from Flying Fish or Takoma.

“Takoma really didn’t back up my music. Also, one of the albums I made with them, “Live At McCabe’s,” wasn’t made in a very comfortable situation. I was playing in an OK-now-show-me-you-can-play situation that night. That’s not one of my favorite albums.”

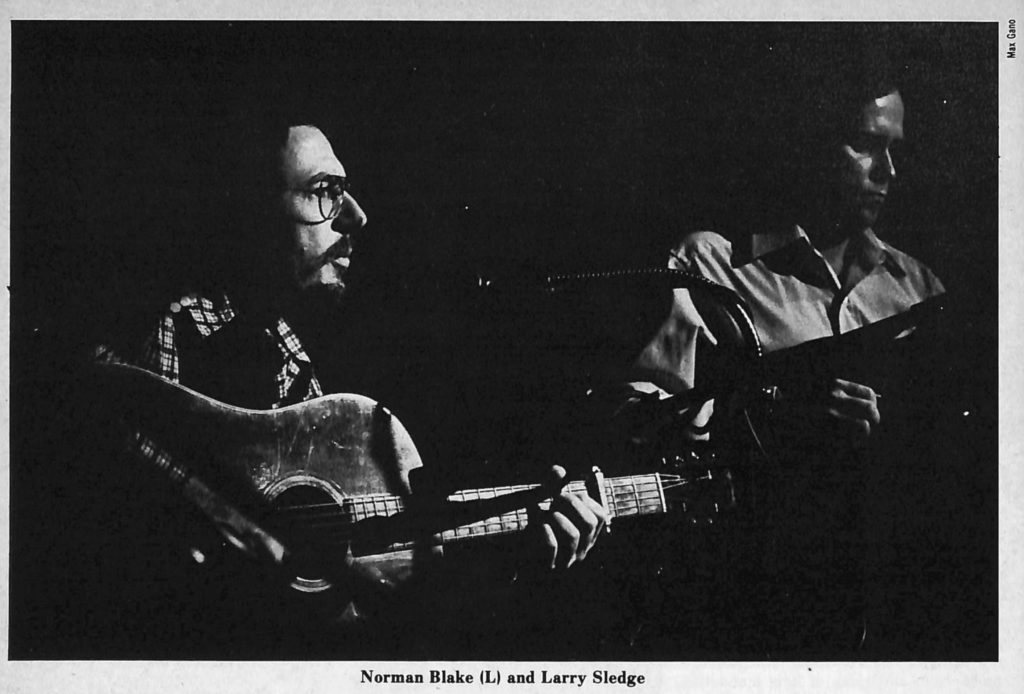

No doubt Blake has passed every OK-hot-shot-do-your-stuff test he’s ever been subjected to. Especially when it came to flatpicking on the guitar, the style for which he is best known. Over the years, unlike his approach to material selection and album production, his vaunted picking ability has continued to expand. “My guitar playing is innovative in that I play long lines of notes on top of a bass line. It’s improvisational, very much like jazz.” Indeed, it’s the guitarist’s complex, melodic solo runs built on the simple, traditional themes that elicit the majority of whoops and hollers during one of Blake’s live performances.

“When I’m at home I spend more time fingerpicking than flatpicking. I fingerpick more at home than when I’m on stage.”

Norman Blake’s initial musical influences were the musicians he was brought up on, people like Roy Acuff, the Monroe Brothers, the Carter Family and Merle Travis. Now when asked to name influences he’s liable to name anyone from a classical guitarist to a jazz player. Blake is certainly no longer influenced by any one style. “I’d say I’m influenced by anything I like. On the other hand not everything I like is necessarily an influence on me. I really like John Renbourn but I’m not influenced by him. Some of my favorite musicians are as far away from my style as you can get.”

In discussing Norman Blake circa 1982 above all one is talking about a self- starting, hard-working musician who is just where he wants to be. One gets the feeling in talking to Blake that he would have it no other way besides his own. The 44-year-old veteran is as serious a musician as one could hope to meet in old-time music. As a result of his insistence on taking himself seriously, and on his audience to take his music seriously, Blake has avoided the jaded cynicism of many of his contemporaries. It is impossible to picture Blake ever viewing his music as “disposable trash” as some rock musicians view their work.

Now I don’t see the music of Norman Blake or the Rolling Stones, for example, as trash. But the difference in the attitudes of the two artists is significant. A musician who is 100% immersed in their music is preferable to those who dodge their music’s importance. “I don’t like tongue-in-cheek music,” is the way Blake put it. “It always bothers me to see a musician making fun of their art while creating it.”

So if you’re playing the word association game with your therapist and he/she mentions “Norman Blake,” you should return with “serious.” You also might want to include words like “independent” and “artistic freedom.” Even though Blake achieved fame by playing sessions and tours with big names like Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, he is happier now because, “There’s more freedom as a solo performer than as a session player.”

Readers of traditonal journals are of course familiar with the warring factions in the continuing debate over the value of “progressive” acoustic music versus the more traditional sounds. Blake readily aligns himself with the traditionals. “Yes, I suppose you could say I’m a purist. I’ve always said there are two types of music—good music and bad music. Good music is not always what’s popular. Popularity does not always pertain to quality.”

Such anti-populist sentiments might easily annoy the more egalitarian among us. Does not a person who states that “there’s good music and bad music” run in a similar attitudinal vein as those who claim that classical music is the only “good” music or that pre-modern, non- abstract painting is the only “good” art? In this light there is another side to Blake’s serious personality aside from the welcome, unjaded dedication to his music. On the darker side one can see a humorless, stubborn unwillingness to allow room for other styles and tastes.

The picker went on to relate his frustration with contemporary tastes to his own live performances. “Audiences are geared toward the obvious in music. They’ll react to a fast guitar solo but they won’t pick up on the subtle part of a performance.”

Norman Blake’s music has enough depth to be appreciated on many different levels. If you want to hear hot, flashy licks, tastefully melodic runs or complex improvisation, you’ll encounter all of them at a Blake show or on a Blake album. If you want to hear a nice adaptation of a fiddle tune for the guitar, an old Appalachian railroad song, or a delightful Cajun waltz, Blake can provide you with any of those, too. Listen to the music of Norman Blake anyway you please. You’re sure to come away with many musical rewards, even if you don’t listen to his music the way he wants you to.