Home > Articles > The Tradition > Muleskinner & Clarence White

Muleskinner & Clarence White

Fifty Years Ago a Landmark Band was Formed and a Guitar Legend Passed

Muleskinner

The story of the legendary, extremely-short-lived band Muleskinner began fifty years ago when fiddler Richard Greene received a phone call from the public television station in Los Angeles. The station asked Greene to put together an all-star band of younger bluegrass musicians to appear in a concert program with Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, a “father and sons” concept.

Greene recruited a great band for the program, consisting of Peter Rowan (guitar, lead vocals), Clarence White (lead guitar, duet vocals), Bill Keith (banjo) and David Grisman (mandolin, harmony vocals), with Stuart Schulman on bass. The guys were all old friends who had worked together in several contexts.

Rowan, Keith and Greene had all been Blue Grass Boys in the 1960s. Rowan and Grisman played together in the rock band Earth Opera, while Rowan and Greene were in the rock band Seatrain. Keith and Greene played together in Jim Kweskin’s Jug Band and the Blue Velvet Band. White had not played in a band with any of the others, but had played with Keith at the Newport Folk Festival and had jammed with the others.

The plan for the evening was for the then-unnamed band of youngsters to open the concert with a set, then Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys would play a second set, and the show would end with both bands on stage for a jam session. Unfortunately, Monroe’s bus, the aptly (if unironically) named “Bluegrass Breakdown” did just that, broke down…in Stockton, California, a good 330 miles from Los Angeles.

A phone call later, just a few hours before the taping, the opening act was now the whole deal. No problem. The guys rehearsed for a couple of hours and came up with a set of 13 songs and tunes. There were two originals that have gone on to become classics: “Land of the Navajo,” one of Rowan’s signature songs over the years, and Grisman’s “Opus 57 in G Minor,” a very early example of “Dawg” music that Grisman had informally recorded at a festival in 1966 with Keith and Artie Rose.

The concert was recorded and filmed before a live audience of maybe 150 people on February 13, 1973, at the studios of KCET in Hollywood. It was a tremendous performance by bluegrass music’s first “super-group,” the forerunner of such outfits as the Bluegrass Album Band and Longview. White, Grisman, Keith, Greene and Rowan were all innovators at the peak of their powers, each on the cusp of individual careers that would honor bluegrass traditions but also carry the music into the future.

The finished, thirty-minute-long program (which was aired in September 1973 and is now available on DVD and YouTube) included just eight of the 13 numbers the band had performed: “Dark Hollow,” “Land of the Navajo,” “Knockin’ on Your Door,” “Red Rocking Chair” and the instrumentals “New Camptown Races,” “Blackberry Blossom,” “Opus 57 in G Minor” and “Orange Blossom Special.”

The remaining cuts are contained on the Muleskinner Live CD, first released in 1994: “Going to the Races,” “Eighth of January,” “I Am a Pilgrim,” “The Dead March” and “Sitting Alone in the Moonlight,” on which pop/blues singer Maria Muldaur superbly duets with Rowan.

Keith went back to his home in New York after the concert, but at least some of what was now known as Muleskinner played a weekend engagement (billed as the “Bluegrass Drop Outs”) at the Ash Grove, the leading folk/bluegrass club in Los Angeles. The band also landed a one-record deal with Asylum Records, a new label started in 1971, which was by 1973 part of Warner Communications.

Muleskinner entered the studio in late March to begin work on an album that would be released as Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam. (Peter Rowan remembers that Joe Boyd, who co-produced the album with Richard Greene, wanted to title the record Soft Pore Corn.) The line-up and instrumentation were the same as for the concert, with a few changes: Keith played pedal steel guitar on a cut, White played electric guitar on a few cuts, the bass slot was filled by John Kahn and John Guerin played drums on a couple of cuts.

Surprisingly, the album contains only two songs the band had performed on the television program a few weeks earlier: “Dark Hollow” and “Opus 57 in G Minor.” The rest of the material leaned heavily on the Bill Monroe songbook—“Muleskinner Blues,” “Footprints in the Snow,” “White House Blues,” “Roanoke” and “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome” a sublime White-Rowan duet and one of the high points on the album. (Oddly enough, the Bill Monroe-Hank Williams co-write “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome” was mis-identified on the original LP jacket, on the CD cover and probably on down the reissue line as “Blue and Lonesome,” a big mid-1960s blues hit by Chicago harp player Little Walter Jacobs and a very different song.)

“Blue Mule” and “Runways of the Moon” are Rowan originals, while “Rain and Snow” is a song he learned from old-time singer/banjo picker Obray Ramsey. “Soldier’s Joy,” a fiddle tune dating back to 1760s Scotland, is a showcase for Clarence White and helps to demonstrate how he rewrote the rules of bluegrass guitar. His playing is blindingly fast and intricate, with a distinctive and highly idiosyncratic sense of rhythm and timing that is instantly identifiable, hard to duplicate and almost impossible to master.

“We finished the entire recording in two weeks,” wrote Peter Rowan in the liner notes to the CD reissue of Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam. “We played as we felt it, coming out of a bluegrass-rock tradition in those early days of the 1970s. Clarence’s gentle soul was our unifying force, holding our music together; we had all the time in the world and no idea how quickly things would change.”

For some reason(s), Warner Bros. dragged its corporate heels on Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam, delaying its release a full year, until May 1974. Perhaps the album got lost in the shuffle when Asylum was absorbed into the Warner empire. The record didn’t sell very well at any rate, and the label let it go out of print after just a few years. The Texas label Ridge Runner reissued the album in 1978, as did Sierra Records in 1994, on CD for the first time.

According to Rowan, Muleskinner was intended only as a one-off concert done solely for the television program. Because performing together turned out to be so much fun, they decided to make a record. And that was that; there were never any plans for touring.

Rowan and Grisman were already putting together and rehearsing a band called Old & in the Way with banjo player Jerry Garcia, who also played in a little band called the Grateful Dead. Clarence had reunited with his brothers and bluegrass, and that was to be his immediate focus. Greene and Keith had their own solo careers going, as well.

It would be hard to overstate the importance of the Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam and Muleskinner Live records. The full band played only one gig—one set, really: a total of 13 songs and tunes—but these two albums have been tremendously influential and closely studied for six decades now. Both albums are essential for all bluegrass students and aficionados, but Potpourri is especially valuable, as it includes Clarence White’s mind-bending playing on both acoustic and electric guitar and is the best all-around display of his gifts on record.

The stars most certainly aligned on February 13, 1973. It was but a moment in bluegrass history, but what a moment it was…a Ground Zero of sorts for modern bluegrass. Much of what would come later in the 1970s and 1980s and even up to today can be traced back to this one night on a small television soundstage in Hollywood. And it all came about because the Bluegrass Breakdown broke down.

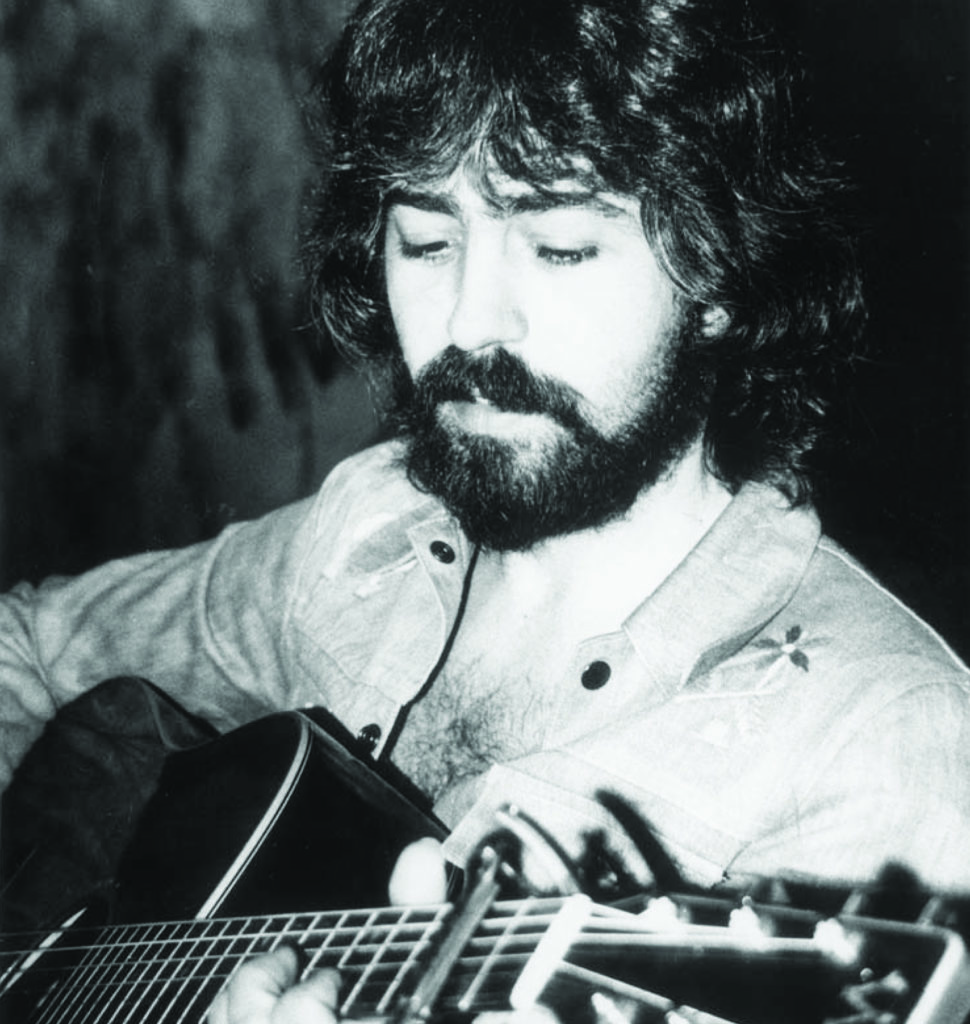

Clarence White’s Passing

It’s hard to believe that Clarence White has been dead fifty years. One of the most celebrated and respected guitarists in bluegrass history, White blazed a new path for guitar players. He was an innovator of the first rank, and if he’d lived longer, there’s no telling what peaks he might have scaled, what magnificent music he might have bestowed on us.

His playing is still being dissected and parsed, the nuances teased out and analyzed a half-century later. He is cited as a major influence upon many great guitarists who have followed in his footsteps, including Tony Rice, David Grier, Marty Stuart, Charles Sawtelle, Russ Barenberg and others. Clarence White’s legacy is secure for the ages.

Clarence began his professional music career in 1954, at the age of 10, working with his older brothers Roland (mandolin) and Eric (bass) in a trio first known as the Country Kids, then the Three Little Country Boys, then the Country Boys. Within just a couple of weeks after the White family moved from Maine to Burbank, California, the brothers were performing regularly on top country music television and radio programs throughout the Los Angeles area.

The Country Boys became a quintet with the addition of Billy Ray Latham (banjo) and LeRoy McNees (Dobro) and began playing at the Ash Grove, the band’s home base for the next few years. The band recorded a couple of singles in 1959, and, in 1961, appeared on two episodes of the hit TV series The Andy Griffith Show.

Because there were already at least two bands in country music using the name, the Country Boys became the Kentucky Colonels with the release of the band’s first album, The New Sound of Bluegrass America in 1963. It was the band’s second album, Appalachian Swing! in 1964, that introduced the world to the lead guitar playing of Clarence White.

The world was astounded. Nobody had ever played guitar like that. His style combined elements from the playing of Doc Watson, Don Reno, country guitarist Joe Maphis and Belgian Romani jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt, filtered through Clarence’s singular and sophisticated musical understanding of time, rhythm, phrasing, syncopation, melody…and the banjo style of Earl Scruggs, upon which Clarence’s crosspicking was based.

In those days before bluegrass festivals, the Kentucky Colonels played mostly on the west coast, with a couple of significant exceptions. The band did a tour in 1963 of folk clubs in Denver, Detroit, Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Cambridge, and Washington, D.C. The Colonels went back east the following year, the high point being an appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in July. Many of these shows were recorded by fans, and tapes were avidly traded among enthusiasts. Many of the Kentucky Colonels CDs that have been released over the years were sourced from those tapes.

After the Kentucky Colonels broke up in 1965 because they couldn’t make a decent living playing bluegrass, Clarence concentrated on the electric guitar and doing session work. He gigged with the Roustabouts and Nashville West (aka the Reasons) and played on records by the Gosdin Brothers, Gene Clark, Rick Nelson and the Byrds, most notably on that band’s landmark album Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

White joined the Byrds in June 1968. He would be on five albums over the next five years. The best of them was (Untitled), a double-album which includes two sides of live material, that show Clarence at his absolute, otherworldly best. Also essential for the same reason is Live at the Fillmore—February 1969.

Clarence was a genuine force of nature on the acoustic guitar. On the Fender Telecaster electric, his playing truly reached another dimension, twisting and turning and bending like a pedal steel. Once again, nobody had ever played guitar like that. It was as if Clarence had discovered—or created—a secret language of the guitar. It’s no wonder Jimi Hendrix was a fan.

Clarence White was sitting on top of the world the summer of 1973. His five-year stint with the Byrds had ended in February, and he had reunited with his brothers Roland and Eric to play bluegrass, working as either the White Brothers or the New Kentucky Colonels, with Herb Pedersen on banjo. The band had successfully toured England, Sweden and the Netherlands in May (with banjo players Pedersen and Alan Munde) and played at a bluegrass festival at Indian Springs, Maryland. Clarence also had a three-record deal with Warner Bros. as a solo artist, the label having promised him he could record whatever he wanted.

With a rare Saturday night off, Clarence and Roland drove over to Palmdale to a club called BJ’s, where brother Eric was playing bass with a country band. Clarence and Roland sat in with the band, Clarence playing his hot-rodded Telecaster. That was the last music he ever played.

Clarence and Roland were putting their instruments into their car after the gig when a drunk driver roared up and slammed into Clarence, throwing him into Roland, who flipped backward over another car. Roland suffered a dislocated shoulder. Clarence did not survive his massive injuries and died on Sunday, July 15, 1973, at the age of twenty-nine.

The dedication on Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam says it best: “To Clarence White, a virtuoso human being and guitarist.”

Paying Tribute

Adam Schlenker always knew this night would come and that this concert would be performed. He just didn’t know when it would happen. Schlenker is the Coordinator of American Roots Music Studies at Denison University in Granville, Ohio (27 miles northeast of Columbus). He is also both a fervent Clarence White devotee and the guitar player and singer in the bluegrass band Appalachian Swing.

As the name might suggest, Appalachian Swing is a band deeply into the Kentucky Colonels. Adam is quick to point out, though, that his band is not a tribute band. “I wouldn’t call us a Kentucky Colonels cover band,” he says, “in the sense that we try to sound just like them and play the exact same breaks and all that. It’s just that we’re inspired by the sound that they made and their whole approach to bluegrass.”

Schlenker, like many bluegrassers who came up in the 1970s and 1980s, discovered Muleskinner—A Potpourri of Bluegrass Jam at a formative age and was profoundly affected by the album. “The Muleskinner albums are just some of my all-time favorite music. Clarence’s playing at that time was just refined to something unreal. Those albums have been part of my DNA for years,” he says.

One of Schlenker’s responsibilities at Denison is to produce a two-day bluegrass festival on campus every February. When he realized that the dates for the 2023 festival were almost 50 years to the day of the Muleskinner television show, he knew the time was right to do the Muleskinner idea. Adam had long told the other members of Appalachian Swing—Hayes Griffin (mandolin, vocals), Todd Sams (banjo), Chase Potter (fiddle) and George Welling (bass)—that he wanted some day to perform the Muleskinner material on stage. They were ready to go.

As a five-piece band, Appalachian Swing could cover all the instrumental parts on the albums. What they lacked was a Peter Rowan-like singer. In an “aha” moment that would elevate the concert from a cool idea to something sublime, Adam decided to see if Rowan himself might be up for the idea. As it turned out, he was.

“I wasn’t even aware of any anniversary coming up,” says Peter Rowan of talking with Schlenker. “Once Adam explained to me what he was trying to do and that the band had learned all the material on both albums, I thought ‘This is too good not to do.’ It just felt right and I said I’d do it.”

“The band worked up all 24 songs and tunes on the two albums,” Adam relates. “We could play them all, in the original keys and using the original arrangements. Knowing we had only one rehearsal with Peter and not knowing which ones Peter would want to do, we wanted to be as prepared as possible—and we were pretty solidly prepared.”

Appalachian Swing mandolinist Hayes Griffin laughingly admits to being “pretty obsessive” about his interests. Still, his level of preparation indicates how seriously the band took this concert. “I sat down and worked out every single part [of Grisman’s] on both records, and transcribed all of his licks and fills and solos and really got inside of it. I then figured out which things I might want to play exactly as Grisman did, and which things I maybe wanted to play ‘in the style of.’

“I wanted to strike a balance of being true to the record and showing that respect—the fact that we had studied it like it deserved to be studied. But I also wanted be Hayes Griffin, the mandolin player, and honor the music that way, by using their music as an inspiration for my own.”

“At our rehearsal [the day before the show],” says Adam, “we gave Peter the complete list of the material we had learned, and he made the choices of what we would perform. It was completely up to Peter. He said, ‘We gotta do ‘Runways of the Moon.’ I haven’t done that since we recorded it.’”

The concert was held on Friday, February 17, before a capacity crowd of nearly 900 people in Swasey Chapel, a beautifully ornate 100-year-old building on the Denison campus. The show was opened by the Denison American Roots Music Ensemble, a band made up of students in Adam’s program.

Peter Rowan and Appalachian Swing then roared through a set of nine songs and tunes from the Muleskinner albums: “Dark Hollow,” “Land of The Navajo,” “Opus 57 in G Minor,” “Rain and Snow,” “Soldier’s Joy,” “Footprints in The Snow,” “Mule Skinner Blues,” “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome” and, yes, “Runways of the Moon.”

As icing on the cake, the encore consisted of three of Rowan’s best-loved songs, “Panama Red,” “Midnight Moonlight” and “Walls of Time.” Adam switched to the Telecaster on the cuts on the record where Clarence did, and the band was joined on those cuts on drums by Seth Rodgers, a percussion instructor at Denison.

“It was really fun,” says Rowan of the show. “The concert reawakened part of me, in that I hadn’t played some of those songs in fifty years. And they were fresh as can be. We never knew the record was anything important, that anybody really cared about it. It’s been a long time, and nobody talks about that record as being significant or anything. I never knew anybody cared.

“Playing the show with Adam and the guys was kind of a redemption for me. It’s so touching that people wanted to learn all this material as a contribution to the bluegrass repertoire. I felt honored that they made such an ambitious effort.”

It’s a pretty big deal to make one of your dreams come true, and Adam’s dream turned out better than he hoped. “There was a moment early in our rehearsal on Thursday when Peter saw my old Telecaster sitting there, and his eyes just lit up. ‘I wanna hear that,’ he said. So, we started playing some of the electric stuff, and he started getting a sense of us. We could tell he sort of lit up seeing the potential of what we could do and what this show might be.

“That changed the demeanor of the whole show for him, I think. It changed from ‘We’re just gonna go through this set list of songs I recorded fifty years ago’ to ‘We’re gonna make some music tonight, fellas.’ The whole thing got more living. It was less about following the arrangements and more about what we were going to do as musicians. It kind of broke things free.

“Peter was into playing and into playing with us. That allowed us to just go out on stage and be musicians together. I never anticipated that at all, and it was just a super-cool experience. Playing my Tele and singing the duet on ‘I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome’ with Peter was just such an absolute delight, one of the high points in my life. I was grinning from ear to ear. The response was remarkable. It was electric in there, such an amazing night. It was definitely one for the books.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Muleskinner