Home > Articles > The Archives > Master of the Dobro—LeRoy Mack

Master of the Dobro—LeRoy Mack

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1991, Volume 25, Number 7

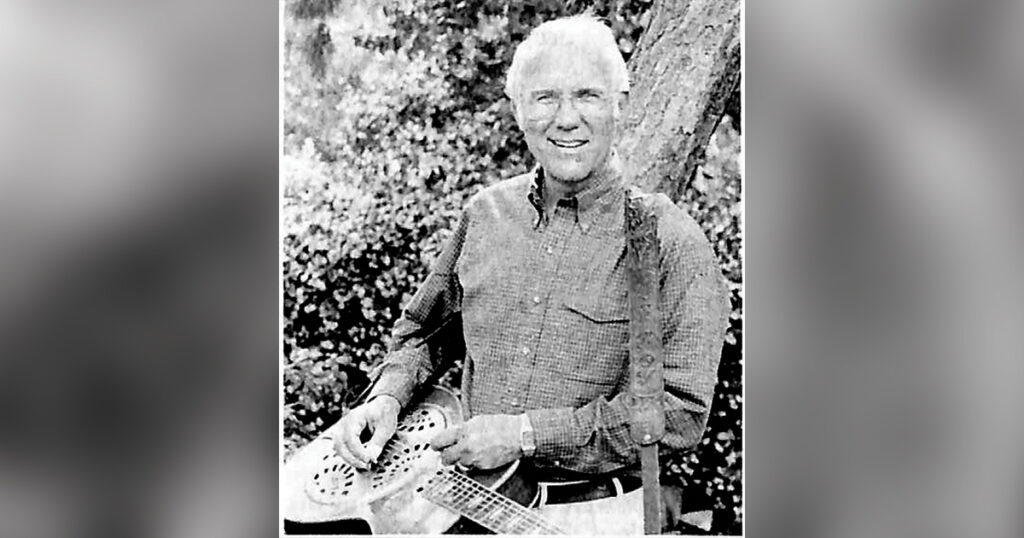

The great Dobroist LeRoy (Mack) McNees, best known as a member of the Kentucky Colonels from the late ’50s to the early ’60s, is alive and well in Sun Valley, California, in the L.A. area. He’s a prosperous businessman, owner-manager of Rusmar High Lift Equipment Rental, which rents construction equipment.

McNees, who dropped the quest for musical fame nearly 30 years ago, plays with the Born Again Bluegrass Band. He expresses amazement that fans still know his name.

Perhaps it’s not so amazing. The Colonels achieved legendary status, due partially to McNees’s bright, rhythmic Dobro playing. Record producer John Delgatto, in liner notes to “Hound Dog Ramble,” recorded by McNees with Byron Berline and John Hickman, said that to compare McNees’s playing with that of other Dobroists would be “akin to comparing the banjo virtuosity of Earl Scruggs with that of Bill Keith.” (“Hound Dog” is no longer available on LP, but McNees has issued it on cassette.)

If you don’t recognize the name of LeRoy McNees, you probably have heard some songs he’s written, like “If You’re Ever Gonna Love Me” (“If you don’t start treatin’ me a little bit better, I’m gonna do away with me”), “I Might Take You Back Again” and “Just To Prove My Love To You.”

The Born Again Bluegrass Band, a religious-oriented group, has recorded seven albums, the latest being “The Pasadena Kid.” The band’s live performances have included the Grass Valley, California, bluegrass festival, as well as religious events. Personnel: Steve Hatfield, banjo; Craig Wilson, mandolin; Layne Cram, bass and LeRoy McNees, Dobro and guitar.

LeRoy, a Glendale, California, native, fell in love with the Dobro when, as a teenager, he heard Uncle Josh Graves on a Flatt and Scruggs record. LeRoy’s dad played country music on a National steel-[bodied] guitar, but the Dobro was new to him. In a rather remarkable piece of luck, the younger McNees picked up a vintage Dobro for his fledgling efforts on the instrument. He went to a pawn shop to find a Dobro. The shop had none, but another customer, a truck driver, happened to possess one. The instrument LeRoy bought from him that day was covered with red fluorescent paint—it reportedly had been used as a clown guitar by a movie studio—but was a fine instrument, with an all walnut body and a four-way matched back and the serial number 87-X.

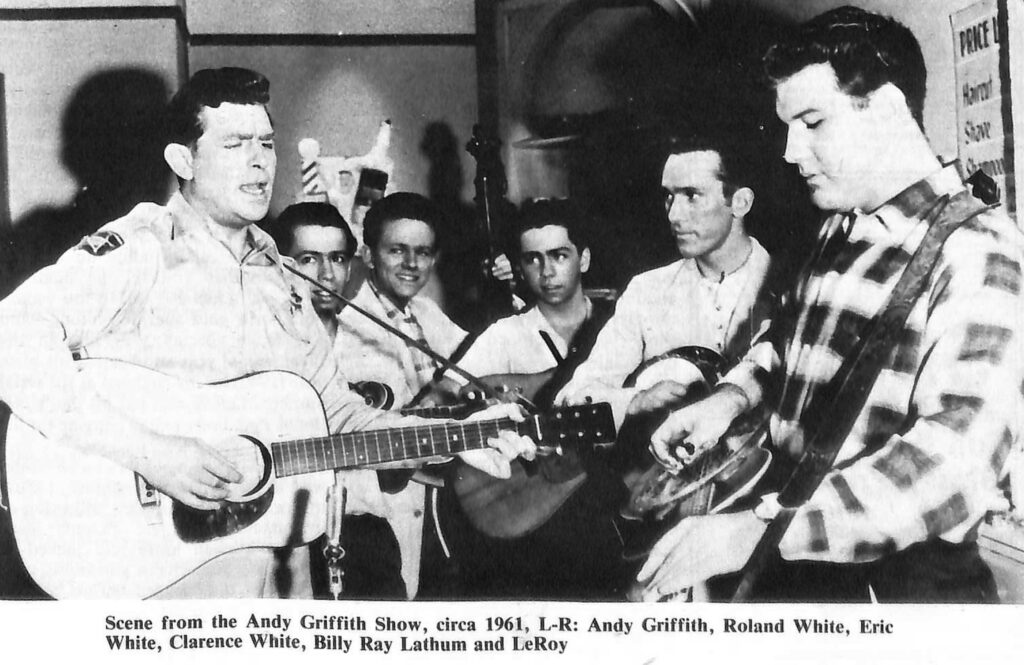

McNees heard the Country Boys, later to become the Kentucky Colonels, on the “Squeakin’ Deacon” radio show and went to visit them; they lived in Burbank, right near Glendale. Members of the band were Roland, Eric and Clarence White and Billy Ray Latham. (Roger Bush joined the group when Eric dropped out.) LeRoy became such a fixture at their rehearsals that he was told, “If you’re going to hang around, you’ve got to learn to play. You’re elected to play Dobro.”

With some help from Billy Ray and by slowing down records to learn from Buck (Uncle Josh) Graves, LeRoy taught himself to play the Dobro. “There was absolutely no one on the West Coast playing bluegrass to learn from in the late ’50s,” LeRoy says.

LeRoy remembers the first time he played on stage with the group: “They tricked me into it. I barely knew where the chords were. They were playing the intermissions for a local dance club. Well, they got me up on stage and I was so nervous I dropped my bar on the floor.”

Roland White was the driving force of the Colonels, demanding four-hour-nightly practices, though all had day jobs.

It wasn’t a problem for LeRoy: “I was all charged up, ready to go.”

Though the Whites were of French descent via New England, they had a traditional mountain sound. Their first record, a single with Lester Flatt’s “I’m Head Over Heels In Love” on one side and “Kentucky Hills” by a friend, Bill Lowe, on the other, won the attention of actor Andy Griffith when it was played on KFOX radio in Los Angeles. The Colonels played on an Andy Griffith Show episode that may still be seen in reruns and recorded an album with Griffith. (The Colonels, the first bluegrassers to play on the show, were succeeded in that role by the Dillards.)

The Colonels stayed together until the late ’60s. Then Clarence White joined the Byrds, Roland went to play with Bill Monroe, Billy Ray joined the Dillards and Roger quit playing.

LeRoy was close to Clarence, who served as best man at his wedding. Clarence was “an outstanding musician and a really nice guy. He had rhythms in his mind and his soul that no one else had.”

Clarence was killed by a drunk driver more than a decade after he played with LeRoy in the Colonels; McNees says he “still remembers the shock” on hearing of the accident.

For a while with the Colonels in their heyday, LeRoy hoped to make a living full-time as a bluegrass musician “That was my dream in life, my obsession.”

Family life would be particularly difficult for a touring musician, LeRoy guesses, though he never did tour with the Colonels after getting married in 1961. (He and his British-born wife, Jan, have two sons, Mark, 20 and Russ, 25.) LeRoy dropped out of the band in 1964, not because of family obligations, but for more complex reasons involving his religious faith.

His quitting the Colonels had to do with a wish to suppress his ego, which, though well-deserved, did not jibe with his spiritual inclinations. LeRoy had “a life-changing encounter with Jesus Christ that changed my motivation in playing music.”

He didn’t want to project the feeling of “look how great I am,” he says. “I decided to live my life in a way to please God.”

LeRoy “put the Dobro under the bed for three years,” taking it out again, finally, at the urging of his wife. He met fellow church-goer and banjo player Steve Hatfield and they formed the Born Again Bluegrass Band, which is still going strong after more than twenty years. An audience member once told LeRoy, “He really makes that Dobro praise the Lord,” which is exactly what he has in mind.

McNees’s activities in recent years have included giving Dobro workshops, solo and with fellow Dobroist Al Perkins. (Perkins, profiled in Bluegrass Unlimited in July, 1988, moved to Nashville from L.A. in ’88 and is now a member of the band performing with Emmylou Harris.)

McNees’s Dobro collection now numbers three, including his original find, another vintage one made in 1930—a model 208 spruce-top walnut body with gold sparkle binding—and one made specially for him in the Bicentennial year and bearing his birth year (1940) on the peghead as the serial number. LeRoy also has his dad’s National steel-body guitar hanging on the wall.

And in closing to those who would wish to learn to play the Dobro, LeRoy offers advice that his fine collection of instruments signifies: “Don’t learn with a kitchen knife and jacked-up strings on your Stella guitar, because you’ll get discouraged before you get started. Get a good Dobro.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This is a wonderful article about a new dear friend, Leroy an Jan are our neighbors and I proud to know the pair of them.

Bluegrass has always lifted my spirits.