Home > Articles > The Archives > Louisa Branscomb—Time To Write A Song

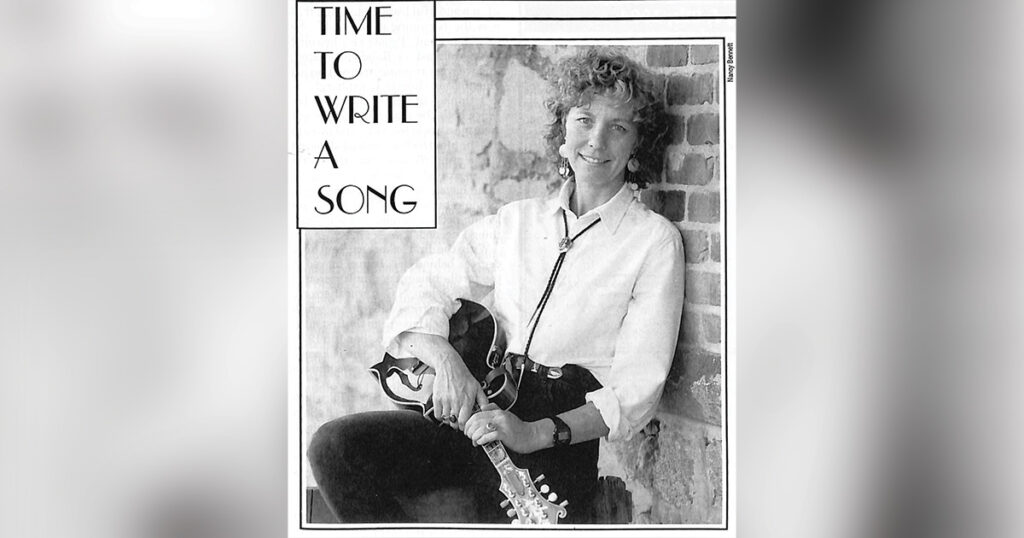

Louisa Branscomb—Time To Write A Song

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1994, Volume 28, Number 9

[Portions reprinted with permission from The SEBA BREAKDOWN, Sept., 1992, Volume 9, No. 9]

“It’s time to write a song. The ice on the river. Is growing much thinner, and soon will give way.

Way down below, the river still flows. The song never froze. You just couldn’t hear it play,

But it’s all right now, There’ll be one more song, somehow.”

People write songs for a lot of different reasons. For Louisa Branscomb, the reason is simple. “God gave me creativity to survive,” she says with sincerity. “If I didn’t have that, I don’t know how I would cope with my experiences. Writing is really like a survival mechanism. If I’m lying awake at night being impacted by something, then if I can write a song, it’s a transformation of those feelings.”

The depth of that answer to a simple question: “Why do you write?,” is characteristic of Louisa, a complex yet charismatic woman whose insight and openness in conversation contrasts with her tendency toward shyness in public. It is only her own avoidance of the spotlight that has kept her name from becoming a household word in bluegrass circles. For Louisa has written over 300 songs, many of which exhibit the same perfect blend of message and melody that made “Steel Rails” the mega bluegrass hit it was for Alison Krauss.

Louisa was born in upstate New York, the daughter of a doctor who “could play the devil out of a honky- tonk piano.” She laughs that she didn’t stay in New York long enough to pick up an accent, and after brief stops in Baltimore and Nashville, did most of her growi ng up in Birmingham. At age four she invented her own way of writing down melodies “by drawing little stair step pictures.” While attending Methodist camp at age seven, she risked being caught lying when she pretended to be sick in order to sneak and play another girl’s ukulele while the others went swimming. But it was not until she went north to college at Randolph Macon, in Virginia, that she began her long love affair with bluegrass music.

Louisa credits her college friend Sally Wingate with initially exposing her to bluegrass, but among early musical influences, she speaks of time spent with a cousin. “He was from Austin, Texas, and he played Lefty Frizzell and Merle Haggard songs. So when I got back to Randolph Macon from this family reunion when I was 17, there was a Martin guitar on my bed, a OO-21, a wonderful little guitar, and that was the beginning of the end.” She laughs out loud. “People were learning to be ‘finished’ at Randolph Macon, and we were running around playing bluegrass in clubs in Lynchburg!

“I think I turned to bluegrass because both the music and the people gave me a world where I could learn to live the life of feeling, instead of the life of the mind. To come into this world where extended families lived in the same house, and hugged and kissed, and just talked about how they were feeling, nothing complicated, was something I needed.”

With the first of her current four degrees behind her, Louisa moved to the fertile bluegrass country around Winston-Salem, N.C. It was there she formed Bluegrass Liberation, which may very well have been the first modern all-female bluegrass band, in 1971, but the band for which she is known the most did not come about until 1973.

That band was called Boot Hill, which Louisa formed with guitarist Sam Sanger, learning to play the banjo in the process. She had a unique reason for choosing the banjo. ‘The banjo is raw power. People weren’t listening to women back then, and I played the banjo because I thought, ‘Well, by God, if I want to get listened to, I’d better play a loud instrument.’ ”

Louisa also fronted the band, a position unheard of for a woman at that time. They quickly became one of the most active bands in the southeast, playing 275 to 300 gigs a year, and selling several thousand copies of each of their three albums. As Louisa puts it, “We were doing fine. I was making enough money to buy a house. How many 24-year-old full-time bluegrass musicians can afford to buy a house?” About her decision to go full-time bluegrass, Louisa has strong feelings.

“One of the smarter things I did was leave the establishment and play bluegrass, because it was so in my blood. I mean, it was like demons. I still have to deal with it in terms of balancing my life. I am more alive when I play bluegrass than any other time. I’m possessed. There is something about it that I cannot replace with any other part of my life.”

Boot Hill lasted for eight years with the same personnel, but after all those years on the road, Louisa found there was something missing. “I had this incredibly rich life of music in my head, but you’re never around people in a normal fashion. You don’t have to learn to relate intimately to people, you don’t have to learn to talk. You just play music, your language is music. My relationships were all at a distance with that audience, or through an instrument or a song to other pickers. When I realized that, I got scared.”

Louisa left the band to move to Atlanta and pursue a career in psychology. She had already gotten a M.A. in counseling from Wake Forest, and subsequently obtained a Ph.D. from Georgia State University. During the period after the breakup of Boot Hill, she joined Frances Munde to help lead another all-female group, Cherokee Rose, which Louisa ranks as the best vocal band she was ever involved with. “We had the drive and feel,” she says proudly. “God, we had feel, and power. That’s what makes a band—feel and power.”

With the completion of her move to Atlanta, Louisa played occasional gigs with T.P. and Sandra Holloman’s Morningside, then formed her own band, Gypsy Heart, which released one recording. That project, released just before the band’s breakup, featured Kathleen Hatfield on lead vocals and guitar, Al Pieper and Sally Brooks on fiddle, DeDe Vogt on bass and harmony vocals, and Louisa on harmony vocals, lead guitar, banjo, and mandolin. In addition to writing all of the songs, Louisa did the arranging, produced the album, and assisted in the engineering and mixing.

The Gypsy Heart album is a charming and thoughtful mix of material, from the sweet, simple bluegrass of “Georgia Home,” to the plight of the battered woman in “Ain’t Justified,” but the strongest songs speak of commitment. “Forever More” and “You And I Look Good In Years” are both songs of long-lasting love and caring. No earth-shattering controversy or deep political significance here, but songs that anyone can relate to, which is exactly what Louisa is aiming for. “I could have songs that were good in the sense that they were universal, that everyone could identify with and like, and that also had an important message, that’s what I would want.” These songs are well crafted, well played, and well sung.

There are many Louisa Branscombs. There is Louisa, the travelling musician, Louisa, the psychologist and author, Louisa, who loves and trains thoroughbred horses, but above them all, or perhaps encompassing them all, there is Louisa, the songwriter, Louisa with the passion for creating. “If I write a song, I could be up 24 hours putting the tracks on tape, because I am so in love with that song. It’s not the getting it done that’s important, it’s the process of doing it, how I feel while I’m doing it.”

She cares deeply about all of her songs, but there is one, written back in 1971, that seems a little special. “I remember sitting in that house in Winston-Salem, and could not put the guitar down because I loved the way it felt to play that song. There is a brief moment of time when I feel that way about everything I have written. There’s a love affair that lasts for a brief time, but it did last a long time with ‘Steel Rails.’”

The song got a lot of attention at the time, Louisa remembers, “I was friends with Larry Lee, the bass player for Mel Tillis. So Larry was playing it on the bus, and Mel heard it, turned the bus around, went back to Nashville, and cut it.” It may be for the best that the over-produced ’70s country version of “Steel Rails” was never released. It was performed by Tasty Licks, a band featuring a young Bela Fleck, and by the Georgia-based band Indian Summer, and recorded by the McPeak Brothers, as well by Boot Hill. A young woman named Alison Krauss happened to hear that old Boot Hill album.

Louisa has a philosophy about the way things happen to her, “Either some huge limb falls off a tree and hits me in the head, and I’m lying there splattered across the street wondering “What just happened?,’ or a golden apple just falls into my hand, and I’m standing there wondering ‘Where did this come from?’ ”

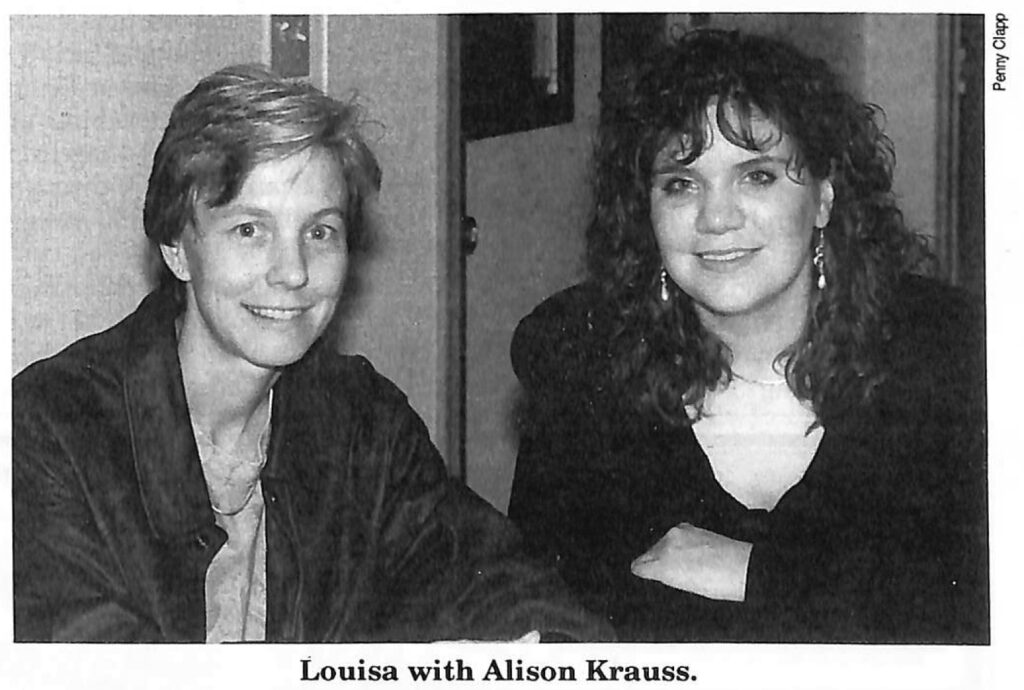

In the late 1980s, Louisa had dropped out of the national bluegrass scene, but as luck would have it, a visit to her grandparents took her to Nashville, and curiosity took her by the Station Inn, where the marquee featured “Alison Krauss with Alison Brown.”

“I was a little out of touch, I didn’t know who Alison Krauss was, but I had heard of Alison Brown, and I knew that she had this TB-6 from John Hickman that was one serial number off from one I had. Anyway, I thought, “Well, look at that, a band with two women in it. I need to go check this out.’ I had my women’s band 17 years ago, and I’ve got this attitude, right? Anyway, I’ve been there for about thirty seconds, and I’m totally humbled. I mean I’m positively blown away. I had to struggle with myself to even get to the point of being able to go up and talk to these women. I was totally in awe.

“So I finally went up to Alison Brown and began to introduce myself, but before I could finish the sentence, she goes ‘You’re Louisa Branscomb? We’ve been trying to find you for the last year! Did you like it? Alison, Alison, come here!’ Meanwhile, I’m going, “Huh?’ I’m totally clueless. Remember, I don’t even know who Alison Krauss is. So Alison comes over and she’s saying, ‘Did you like it, was it OK?’ I’m still lost when she says ‘Your song! We did “Steel Rails” last set.’ Well, I was redeemed. My purpose on earth had been fulfilled. The rest of my life is just what’s in between this and dyin.’ So, Alison goes out and introduces me, and suddenly I’m ‘famous,’” she laughs. “I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.”

The phenomenal success of “Steel Rails” (a lead play on Alison Krauss’ Grammy winning “I’ve Got That Old Feeling” album, extensive video airplay, and winner of the Song Of The Year in 1991 from SPBGMA), and the respect it has brought towards Louisa Branscomb the songwriter, has had a profound effect. She speaks quietly, almost reverently, of the experience. “I came alive, it was like a rebirth. Something has happened to me spiritually. I just got re-connected with everything about bluegrass and about the greater purpose in my little local life. Mostly it’s about reaching people with my music.

“I come from preachers and teachers. One of my grandfathers was a theologian, the other a Methodist missionary. Two of my great-grandfathers were Methodist preachers, horseback type. I come from a family of socially oriented people, they believe in giving back to society, through teaching, or the church. I think I’m coming to a place where I can give back through my music, and I’m getting comfortable with that.”

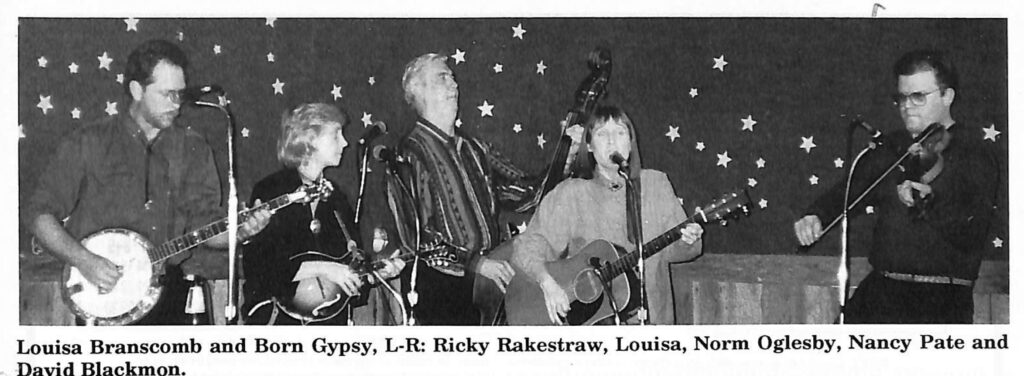

These days Louisa is a regular fireball, or, as she would put it, “We are each a falling star.” In addition to her practice as a psychotherapist, she edits the newsletter for the Division of Women Psychologists of the Georgia Psychological Association, continues raising and training her horses, writes numerous articles for various publications, is active in political causes where she thinks she can help, plays gigs with her current band, Born Gypsy, and has recently released her first CD, again featuring her own original material, all in addition to raising her new daughter, Olivia!

“It’s Time To Write A Song” is a songwriter album, originally released last year on cassette, but remastered and expanded for the CD release. All the songs are Louisa’s, but in addition to her own vocal and instrumental talents, the performers represent a number of talented musicians and singers with whom she has developed relationships. Prominent among those are Scott Vestal on banjo and Randy Howard on fiddle, but also featured are such Atlanta area music scene notables as Jane Baxter, Cyndi Craven, Al Smith, Bill Everett, David Blackmon, and Leesa Lanham. Louisa plays guitar on most cuts, and banjo or mandolin on some. The CD also features members of Louisa’s current band Born Gypsy: Ricky Rakestraw (banjo), Nancy Pate (guitar), and Norm Oglesby (who recently replaced Jane Baxter on bass). The songs they recorded reflect the entire spectrum of human emotion, from love found to love lost, from life to death, and from despair to hope. The music ranges from bluegrass to country, and on to swing. Several of the tunes on this project are expected to be included in future releases by several bluegrass artists.

And what of the future, specifically the future of bluegrass music? Louisa is still in love with bluegrass, but feels there’s room for improvement. She still remembers an incident from her Boot Hill days, when they tried to get a booking at what was one of the biggest bluegrass festivals going, and were told, “‘That’s a good band, but they can’t play here, because there’s a woman in the band.’ Well, Alison played there this year. That just tells you in a nutshell how things can be different.

“There is a concept of the ‘Feminine’ in psychological terms,” Louisa explains, “with a capital F, and I think bluegrass needs more of this. It has nothing to do with gender. It has to do with empowerment rather than competition. It’s about using your power to build others up, rather than to step on or dominate them; about listening to and honoring feelings. The underside of bluegrass is that there is a tendency among some people to decide what reality is, and if it isn’t their version, then that is okay.

“It’s reflected in many ways, down to what the song says. My God, don’t we have enough songs about chopping the woman’s head off and throwing her in the river? Think of what the song says. We don’t need songs that say that, we need songs that say how we should treat each other, with respect. Bluegrass as a giant family has a lot of room for people stretching and opening their eyes a little bit. That’s what the excitement of it is all about, the individual differences between us.”

Louisa currently leads her band, Born Gypsy, and is concentrating on promoting her songwriting. As for her

future, it’s certain that she will follow her own vision. “You can be what society tells you to be, and if that works for you, that’s fine. There will be fewer branches falling on your head, but there will be fewer golden apples.”