Home > Articles > The Archives > Lester Flatt & The Nashville Grass

Lester Flatt & The Nashville Grass

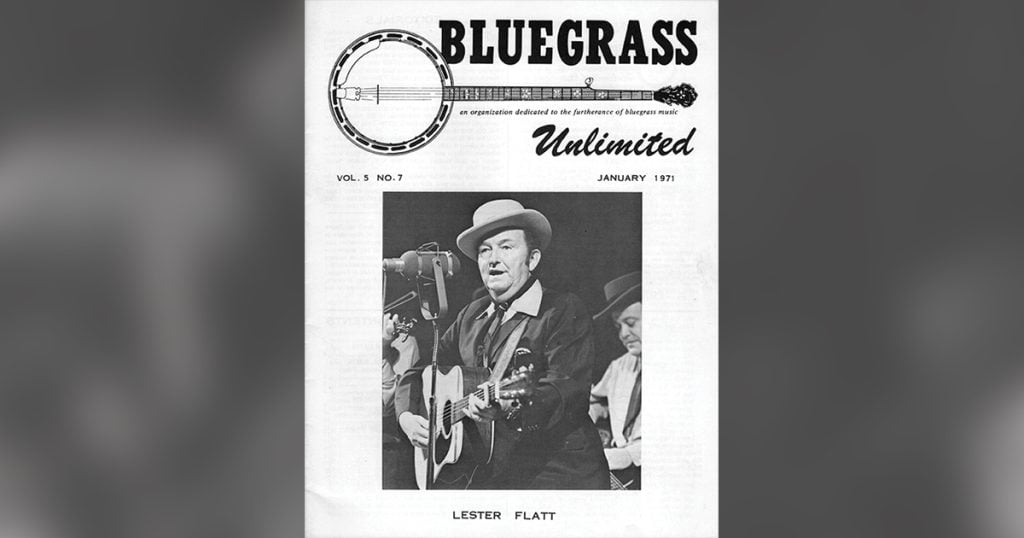

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1971, Volume 5, Number 7

“I’ve always wanted to do what we are doing now,” says Lester Flatt about his new approach to his music. The band currently features Buck “Uncle Josh” Graves, Jack Tullock and Paul Warren, plus two former Blue Grass Boys in the person of Roland White returning to the mandolin and Vic Jordan (who played banjo with Martin and Monroe). Lester was a partner of Earl Scruggs for over twenty years. Together they featured bluegrass in places it had never been before. He recently has signed a contract with RCA, becoming the first traditional country artist to record for them since the Country Pardners in the fifties. The grass’s first release on RCA is set for after the first of the year. Many are looking forward to it and the directions that Lester Flatt is going into. After an interview’ which lasted almost two hours on June 14, 1970 at Culpeper, Virginia my respect for the man has greatly increased.

His “Flatt Out” LP on Columbia, the first and last that he made for them after he and Earl had split up, got mixed reactions. We asked Lester about it.

“I’ve always wanted to do what we are doing now, but you know a lot of folks seem to have a different opinion about recordings. If you are working for a major label, any label as far as that’s concerned, and if they’re paying you to do something, well if they want to add a little something over here or in there it’s hard to say no. You just can’t hardly do that. They’ll prove to you too that they’re selling a lot of records. My first album (“Flatt Out”) on Columbia came out with too much drum on it and too much bass guitar, more than I approved of. But I didn’t have a chance to be in on the mixing of it and hadn’t heard it until it came out. I feel that we had some of the best material on that album of any that I’ve ever been a part of. But it wasn’t exactly my cup of tea as to what came out on the mixing.”

At the majority of the studios in Nashville they have eight channel recording machines and Lester cut this LP accordingly. The increased number of channels makes for a bit more ease in recording. The instruments are all on separate channels and the volume or sound of each can be readjusted after the musicians have gone. But it gives increased control to engineers in the mixing process. The eight tracks are mixed together to form the record which is played on the radio (mono usually) or stereo record. A lot can be changed in the process.

“One of the most important things when you are on separate tracks is the mixing part. Sometimes you never get to hear it. I always like to be in on the mixing but in this case we didn’t get a chance. I was very much disappointed in some of the tunes, especially the banjo. Vic wasn’t brought up enough on his banjo tune.”

When Lester and Earl were together they went the way of the commercial wind. If Bob Dylan was big they would cut Dylan; if something else was big they would go with that. “Well that gets back to what we were talking about a while ago. In this case Bob Johnston (Columbia producer), the guy who recorded us, picked a lot of the material. He also cuts Bob Dylan and we would record what he (Johnston) would come up with, regardless of whether I liked it or not. I can’t sing Bob Dylan stuff. I mean Columbia has got Bob Dylan, why did they want me?” They have always been able to sell a few records on their own; Lester and Earl were second only to Johnny Cash in country record sales with Columbia. “Of course, we were way second; I think everybody is to Cash, but at the same time it was a good rating.

“There’s a lot of stuff that goes on in the record business that I don’t know myself. I know they sell. I don’t know where exactly. It wasn’t anything to cut an album and 100,000 be sold just like that. Just an average whatever you want to call it, bluegrass or country. I’ve never been sold on the name bluegrass. It has always been just good country music to me. We always had what I think you would call a good standard record sale. It never was something that would sell a million overnight but stuff that we’d do this month next year would still be selling. That’s the difference in those that come up this month with a big smash and next month would be gone. Now you notice when we were doing Flatt & Scruggs music as what I call it …. it’s something that we helped to build, we could go fifteen or twenty miles out of Nashville and just stack the place. After we switched and did some of the other stuff, even though you jump to 100,000 on your albums, you could see the difference in the spirit of the country people, the people that made you. It was very easy to see it.”

A lot of publicity went around during the split and we asked Lester to comment on it. “Well there were other parties involved that wanted to do different things than we had been doing. I guess the best way to put it is that it happens in the best of families. Earl has got a couple of boys coming along. They’re working on the Opry I notice and maybe they’re doing the kind of music they want to do. I wish him well but we cannot work together anymore. We tried real hard over the past years and it just didn’t work out.”

Lester has gone toward the more traditional sound. “Now I’m a full believer in that you have to be yourself in music. You cannot be somebody else. When the Beverly Hillbillies record came out, it jumped up to number one and as far as I know that’s the first record of this type of music that has ever been number one on the charts and everybody at the Opry was jumping on our style of music. They wouldn’t cut a record without a banjo on it. But you saw them get away from it right quick. You just can’t change every week and do any good at it.”

The relationship that Lester and the group had with Martha White Mills of Nashville is of interest to many and has been a unique marriage between industry and art. “When we organized the Foggy Mountain Boys in 1948 we came to WCYB in Bristol, Virginia and, without saying it in a bragging way, things were real good for us. Everything was right. Well talk gets around, and it got back to Martha White. One of their salesmen came to one of our shows and saw what kind of business we were doing and told Cohen Williams, who is president of the company. He got in touch with us to bring us into Nashville. Now everything was fine where we were, we weren’t studying to go on the Opry. We were better off than a lot of them on the Opry at that time. We were on a 10,000 watt daytime station and I’ve never seen anything like it. You plugged your shows over the air and it didn’t make any difference whether you put out any advertising or not. That’s how they were glued to that station. It was a noon time show and you would pack them in anywhere you went.”

The show that Lester was referring to was “Farm and Fun Time” which was broadcast over WCYB almost from the time that the station went on the air in 1946 until the late 1950s. Many of the pioneers in bluegrass worked on this show. Among them were Lester and Earl, the Stanley Brothers, Sauceman Brothers, Charlie Monroe and Mac Wiseman. With its proximity to the heart of the Applachian coal mining country it covered the whole southwestern part of Virginia as well as parts of Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina. The show was a tremendous force for traditional music at that time. Other radio stations featuring bluegrass then included WPAQ, Mt. Airy, N.C., WPTF in Raleigh, WWVA in Wheeling, WRVA, Richmond, Va. and WSM in Nashville. Lester and Earl worked on all of them but WWVA. “Well it was real good for us. Of course, one of the other best things that happened was when Martha White picked us up. We’ve been with them for over seventeen years. I guess it’s been good for them as it has for us. I noticed recently in one of the country music publications an interview with Cohen Williams, who said that Flatt & Scruggs and the Grand Ole Opry had changed Martha White from a $250 a week broker business to a multimillion dollar company. Now I don’t think we deserve this much credit but you appreciate somebody in his category thinking about you. It’s been good for both of us.’’

This combination was so close that Flatt & Scruggs cut the Martha White theme song on a commercial LP (Flatt & Scruggs at Carnegie Hall-Columbia CS 8845) “Well you know we played Carnegie Hall in New York and I didn’t think that anybody up there had heard of them and all of a sudden we were hearing ‘Martha White! Martha White!’ This is a good example of the force that radio coverage has. We have our show back on WSM at 5:45 AM CST each morning again. In the fall and wintertime we get mail from way up into Canada and the maritime provinces.

“It’s a funny thing about this Martha White thing. Last year we were over in Japan and we opened our show in Tokyo and we hadn’t been ten minutes into the show when they too were yelling out ‘Martha White! Martha White!’ That was something else.”

Lester and Earl were the first bluegrass band to play for Japanese audiences. There is a very large following for traditional music in Japan and Lester was quite impressed with it. “The reaction to us was so much different than some of the groups from the Opry who went before who didn’t have a banjo. There was some interest over there that we knew of, since we would get mail from some of the boys. They have what they call the Tokyo Grand Ole Opry and use mine and Earl’s picture for the Stage backdrop. So when we got over there we found out that there are 500 bands of our style in Japan alone. All the concerts that we played were sold out four weeks in advance and the admission was around the equivalent of $5.50 which was pretty high. Ages ran from eighteen to thirty. The Japanese promoter asked if we would do an autograph session after the show which we agreed to. They set up tables to give a type of line that would pass by us and get their autographs and then move on. Well we autographed for about forty-five minutes or so and you still couldn’t see the end of the line. The promoters then stepped in to stop it since they were afraid it might go into the next day or more. They (the fans) got pretty upset at that and pinned Jake against this glass thing they had and he was afraid he couldn’t get out. They wouldn’t just settle for an autograph, they wanted to get up to you and touch you and all. When they started rushing us, one of the promoters jumped over the table and grabbed Earl and my chairs and went back down into the basement and way under the stage with the lights off to the other exit. They called a taxi to pick us up over there. Well we got in the taxi to go back to the hotel and we had forgotten to take our hats off and we came up to the stop at a red light and they saw us again and fell in behind the car. They are a very sincere people about this music. They found out what hotel we were in and the phone would ring until 1:30 or 2 in the morning. I finally had to get someone downstairs to stop the calls. It was amazing to me how serious they are about this music over there.”

Lester Flatt, as most of you know, was one of the members of the original Blue Grass Boys. This group had a far-reaching effect on the music. Did Lester think they were anything different? “I guess we didn’t, I guess we really didn’t give it a thought. We were doing what we had been raised up with. That’s the kind of music that we had known. My daddy played the fiddle and the banjo; I started out trying to play a banjo. I didn’t see any of this three-fingered style though. I got to where I could play one pretty good but I wanted to play this Stringbean-drop-thumb clawhammer style. I’d sit and watch my daddy play it for hours. It was so easy for him and I never could get my thumb to work right on that drop-thumb business and I just gave it up. Actually when I went with Bill Monroe in early 1944 he had a different lineup. I had been working with his brother Charlie. … I sang tenor with Charlie. So when I went to work with Bill, I decided I wouldn’t do any more tenor. I wanted to get solid on lead and from that day on I never sang any more tenor. Of course, down through the years I may have sung tenor on the chorus of some of our records but I felt like, if I stuck with lead, I would be better off than try to switch off and do both. The Blue Grass Quartet, if I do say so, was very popular at that time. My first radio experience with this type of music was from the Monroe Brothers (Bill and Charlie). I used to listen to the early morning radio program they had. They were singing good country and gospel songs and it was the kind of music that we had been raised to. So when I went to work with Bill it was no problem to sing about any song we knew. It would just fall into place. You were talking about the changing of the sound, now when I went to work with Bill he had Stringbean (Dave Akeman) playing banjo with him. Bless his heart he’s one of the best fellows in the world but it was a different style than what Earl played. When Scruggs came into the outfit, it completely changed the sound. There’s no way to compare a drop-thumb to what Earl was doing.”

Stringbean did record on Columbia with Bill Monroe a total of eight sides Feb. 13, 1945 two of which; Come Back to Me in my Dreams (C4361) and Nobody Loves Me (C4357) have never been released. He took banjo breaks on two of them. Stringbean plays a two-finger style in lead or melody. It was not unlike three finger style as it is played today. “Yes, but there was a difference. It’s altogether a different sound like I said, we didn’t think too much about it. It all fit together good and we just thought it should be the way it was then.”

One of the contributions that Lester is best known for is his “G” run. Nobody quite plays it the way he does and every bluegrass guitar player uses it. Monroe himself recorded it (on guitar!!) on his original 1939 “Mule Skinner Blues”. “Well it was around before I started using it but I really didn’t use it until I went with Bill on the Opry. At that time we were playing almost everything so fast that it was hard to keep on the beat and that run worked out good for me to get me back on the rhythm. It worked out good and I just kept on using it.”

There has been some controversy about who was playing guitar on Bill Monroe’s Columbia recording of “Little Community Church.” Lester said that he did not play guitar on the record. “I’m almost positive on that one that Earl played the guitar on it.”

After the split, a lot of the recognition Lester and Earl achieved as a team had to be rebuilt though Lester was quite candid about his possible nomination to the Country Music Hall of Fame. “Well I think that there are plenty of them that should go in before we do. I guess all in all we’ve helped country music but I think people like Bill Monroe and Mama Maybelle Carter and people like that should go in …. should have been in …. long before you start talking about us.” His comment was extremely prophetic.

When Lester and Earl started on their own they were one of the earliest to split away from the parent company of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys to form their own group. “Well, I feel like actually maybe Bill might have always had the feeling that we had planned it but actually we hadn’t. Earl, he had to take care of his mother, she was living over in Shelby (North Carolina) and he didn’t like the idea of staying away from home all the time with nobody there with her. To make a long story short it was a rough life. I had made it up in my mind to quit but I hadn’t said anything about it. Earl was going to go home just to get off the road. We had it rough back then. It wasn’t anything to ride two or three days in a car, we didn’t have buses like we do now, and we never had our shoes off. Earl had a textile job before he came to Nashville so I think he was just planning to go back and take care of his mother and work at the mill. After Earl turned his notice in to Bill, you know he was giving his two weeks notice, we got to talking and I told him I was going to quit too. We decided we might go to Knoxville and work as a team or go to work with Carl Story or some group that might need us. I turned my notice in then and before my notice was up, fellows like Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts) said “let me join in with you and we’ll form a band.” So that was how it all happened.

After they left Bill Monroe, Lester and Earl went to Hickory, N.C. for about a week and picked Mac Wiseman as tenor singer and went to Bristol, Va. and WCYB.

We asked Lester about the group that Bill had when Lester went with them. “Well as I said before there was Stringbean (Dave Akeman) and Sally Forrester, Howdy’s wife, playing accordion and a guy from Miami, named Andy Boyette was playing bass. There was five of us all together.”

After the mention of Howdy Forrester’s name we launched into a discussion of fiddlers and another name came forth. “Well I tell you in my way of thinking and I really believe this, a guy that should have the credit for a lot of the fiddling that you hear today from the early days of the Grand Ole Opry was Arthur Smith. He was one of the first guys that I ever heard that played this pretty fiddle, this melody stuff. He was one of the first in our part of the country that played that lonesome stuff on a fiddle. I remember it well. It was Sam and Kirk McGee and Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith. Now I had never been to the Opry and never knew what it looked like but I listened to it on the radio.

“Now I know that everybody had to be quiet when he (Arthur Smith) came on because I really loved that fiddle. He was the first that I ever heard playing that double string stuff on the fiddle like you hear today. Now, Paul Warren, if you want to say copy, he plays like Arthur Smith right today.”

Before his tenure with Bill Monroe, Lester worked for a number of years with Bill’s brother Charlie. We asked, since Charlie also plays guitar, if Lester played guitar with Charlie. “Well I did for a while and then he wanted a mandolin sound and which, I never fooled with the mandolin much but I’ve laughed about it a lot… he gave me a raise and I carried the mandolin around. I’d tell Charlie that I carried the mandolin around for the raise. Actually I got to where I could play a few tunes on the mandolin. I could play rhythm all right ’cause Charlie played the guitar himself. Curley Seckler also worked with Charlie a long time but Curley wasn’t with him when I was.” We were curious about the style of music that Lester and Charlie were playing. “Well it was probably pretty close to the Monroe Brothers. I had worked with Charlie in 1943 and before that I worked with Clyde Moody. I don’t know whether you remember it or not but Clyde was in a group called the Happy-Go-Lucky Boys. I worked with Clyde around 1940, 1941 or ’42. My first radio work was at WDBJ in Roanoke, Virginia in 1939 when I was in textile work and we had a group of guys that played around town.”

It was a very interesting conversation, to say the least, and we are looking forward to Lester’s efforts on RCA. Lester and the group can produce some very exciting sounds.