Home > Articles > The Archives > Leon Morris

Leon Morris

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1982, Volume 17, Number 3

The Washington D.C. area is full of veteran bluegrass musicians who learned to play in the ’50s, when both they and the music were young. Over the years, most of them migrated to the nation’s “bluegrass capital” from Appalachia.

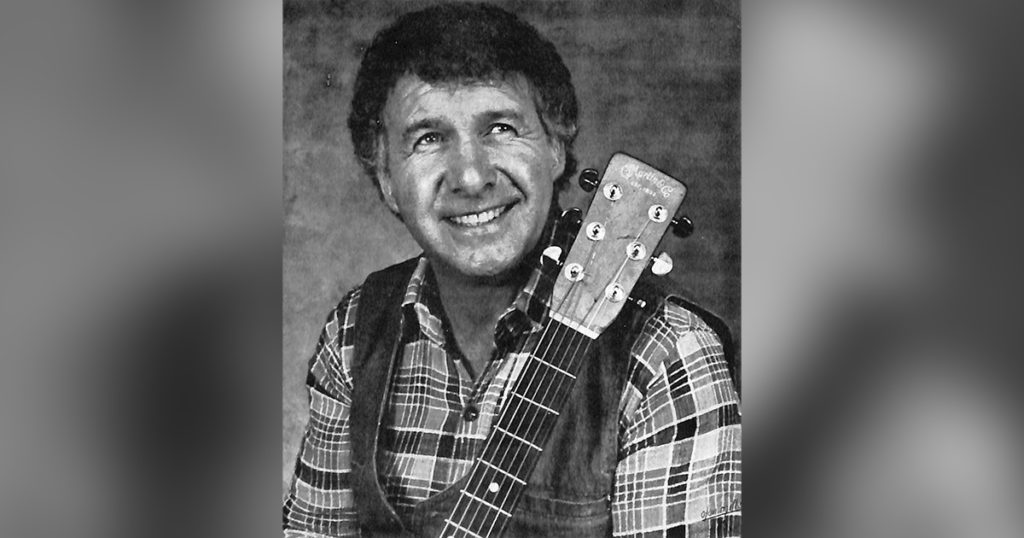

Guitarist and singer Leon Morris, 46, is an exception—he’s from Canada. And, unlike many first-generation pickers who are rarely heard from these days, Leon is still at it, writing songs, recording albums, playing clubs and festivals with his band, the Bluegrass Associates.

Leon, who lives in Alexandria with his wife, Evelyn, and five boys, was born in Toronto and raised in the town of Simcoe, Ontario, in the tobacco belt about 80 miles from the province’s capital near the shores of Lake Erie.

His father was the town’s principal housepainter. His mother played piano and performed with a square dance band.

“The only way you could hear bluegrass music in Canada back then, in the late ’40s, was if you were lucky enough to pick up WSM from Nashville on Saturday night,” Leon says. “Of course, I didn’t know what bluegrass was. But I knew I liked it when I heard the 5-string banjo and the pretty harmony. Mostly we heard country music. Hank Snow was very popular, along with Roy Acuff and Red Foley.”

Leon’s full name is Leon Morris Lamouroux. He had four brothers, Louis, Albert, Bob and Ted. (Ted was drowned in 1969 while living in Portsmouth, Virginia). Leon started playing guitar, an imitation Martin given to him by a sister-in-law, at 12. Louis, the eldest brother, taught Leon the rudiments. “He forced my fingers onto the frets,” Leon grins. “It was a job, but he got me going.”

Leon and the guitar apparently hit it off well, because the following year, 1948, he cut his first record, a 78 r.p.m. on which he sang four songs to his own accompaniment.

“It was a one-shot deal. They cut it as you played and that was it—you couldn’t change it if you made a mistake.”

A few years later Leon bought a mandolin. “When I heard Bill Monroe, I thought, ‘Hmmm. Time to start playing the mandolin. If it’s bluegrass, you got to play a mandolin.’” He went on to learn banjo as well, later playing that instrument with an Ontario group called the Mainstreeters, an alumnus of which, Gordie Tapp, currently is a member of TV’s Hee Haw cast.

It was on mandolin that Leon first performed publicly. In the mid-’50s, he met Jim Ross, a native of Danville, Virginia, and they teamed up as “Jimmy and Leon.” Appearing in the Toronto and Hamilton, Ontario areas, “just anywhere we could get a job,” Leon played mandolin, Jimmy guitar, and they sang in the pre-bluegrass duet style of the Monroe and Louvin brothers.

Their first significant gig was at Blue Valley Park, about 30 miles outside Toronto, where a festival was being held. En route to the park, they spotted two hitchhikers with fiddle and banjo.

“We asked them if they’d take out their instruments,” Leon remembers, “and ‘pick one.’ So they did, and they sounded pretty good. They were from the New Brunswick area. We played together as a band at the festival. I believe that was the first time I ever worked with a banjo player.”

(In 1975 the Bluegrass Associates played at Carlisle, Ontario, where a large bluegrass park has since been established. “All of a sudden this guy came up and said, ‘Do you remember me?’ ” It was Vic Mullen, the hitch-hiking banjoist, who now-works for radio station CBC in Hamilton, promotes bluegrass, has his own band and has become a fiddler. “So,” Leon says, “Vic ended up playing on my latest album 25 years later. Small world!”)

In the late ’50s, in search of more bluegrass activity, Leon, now in his early 20s, began crossing the border to Detroit, some 100 miles from his hometown. There he heard Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys, a major band that at the time included J.D. Crowe on banjo, Johnny Dacus on fiddle and Earl Taylor on mandolin. “They worked with a bass at a club with a number—I forget what-for a name.” He met a number of other musicians, among them Wendy Miller (current mandolinist with J.D. Crowe’s band, the New South), and found work in a small club in Pontiac, Michigan.

Leon’s brother Albert had a painting business in Detroit, providing Leon a place to stay and a source of extra income which enabled him to purchase a Martin D-28 guitar in a pawnshop.

On one of my trips to Detroit, my old car broke down,” Leon recalls, “and this gentlemen stopped to help me push it off the road. He saw the Ontario tags and asked where I was from.” When Leon said he was a Canadian, working in the United States, “the guy casually pulled out a badge and asked me if I had a visa.” Leon said he did not (“I didn’t know what a visa was”) and the officer took him to “the station,” told Leon he had to return to Canada and explained how to obtain a visa.

Leon got a permanent passport and returned to the States for good in 1961.

In Detroit, Leon’s ability as a bluegrass vocalist and guitarist—he could play lead breaks as well as solid rhythm—began to be noticed. Earl Taylor was forming the Stoney Mountain Boys (which subsequently made history being the first bluegrass band to perform at Carnegie Hall) and had recruited Walter Hensley on banjo, Billy Baker on fiddle and “Boatwhistle” (the late Vernon McIntyre) on bass. In need of a guitarist, they sought out Billy Gill, “a fine musician originally from the South,” who turned down the offer, having just gotten married. Gill suggested that Taylor query Leon; Leon accepted. “I thought, ‘Well, here’s my chance,’ so I packed up my duds and went.”

An eight-month period of dues-paying was in store. The band first played clubs in Detroit. “It was pretty bad—hard to get any work,” Leon says. “So I pawned everything I had—a Gibson RB-150 banjo, my record player and everything but my guitar.”

Taylor told the band members that things would be better in Chicago, but they weren’t. The one club willing to try bluegrass would hire only a trio. “We ran into Al Capone’s brother,” Leon says, “and were told they would only hire three of us. Billy Baker and Boatwhistle had to stand on the floor, with the fiddle and bass, and act like they were newcomers who wanted to join the band. But they weren’t allowed. They didn’t like that.”

On somebody’s word that bluegrass “would really go good in Kansas City, Missouri,” the band decided to move on. “We just had to go and find out. So we scraped up enough money to get a flat. Earl had a Gibson J-200 guitar, a good one, but it had a crack in it. We used shoe polish to camouflage the crack and sold the guitar for $60, giving us enough money to make it to Kansas City.”

The musicians walked into the Buckeye Club, auditioned and were immediately hired. “It wasn’t much money,” Leon says. “We played there for several weeks, Friday and Saturday nights, and then got another job, Tuesdays and Thursdays I think it was, at a real nice place. For a while we were doing all right.”

But stress was taking its toll.

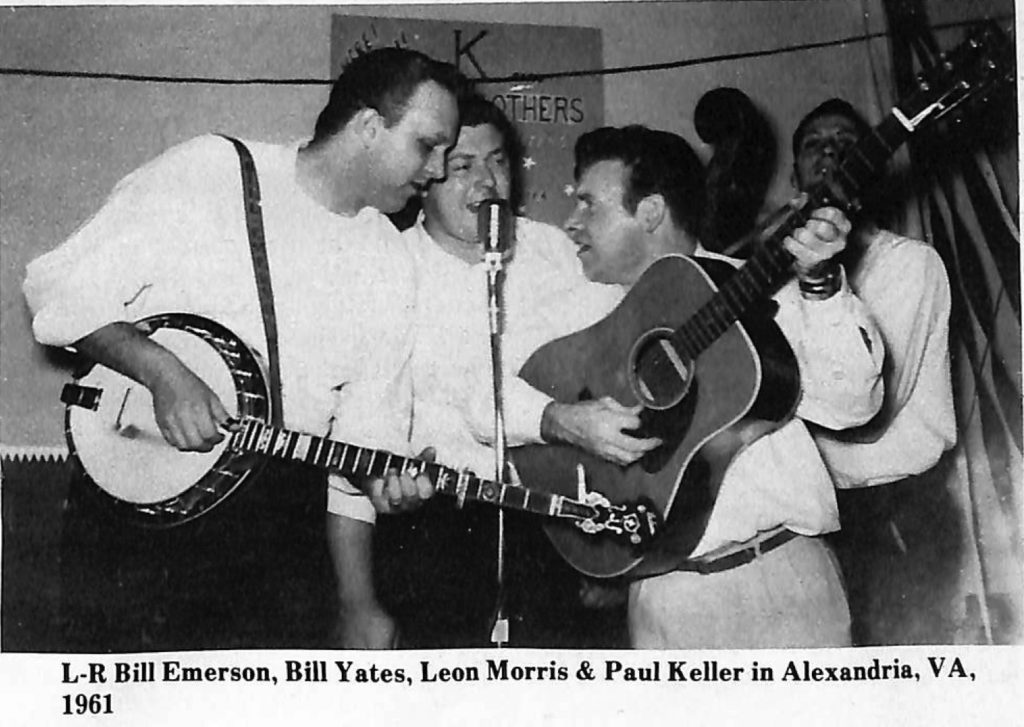

“We went hungry a few times, and our nerves were just about shot. It was a shame, but we busted up and Earl, myself and Walter went to Baltimore. Then Walter got a job playing with the Country Gentlemen for a few months, and we moved to Arlington, Virginia. Earl stayed in Baltimore with his wife. This was the fall of ’61. “The Yates brothers, Bill and Wayne, knew Charlie Waller and had heard that I was there—I don’t know how, but guitar players were scarce back then—and they came around and approached me with a job offer. I said, ‘Well, sure, I don’t have anything to lose.’”

Leon played with the Yates Brothers for about a year and then found employment with Yellow Cab. “I drove a cab around Alexandria, Virginia, for a year, played music here and there, got married and settled down, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Leon’s next musical venture was as a guitarist with Jack Tottle and the Lonesome River Boys in the mid-60s. The band, with Tottle on mandolin, Don Miller on fiddle, Danny Kimmer on banjo and Jim Cox on bass, cut an album for Folkways which was never released. Leon subsequently joined the Greenbriar Boys, a seminal New York-based band, for several tours and then “sort of laid off the music for three or four years. I just took a real long rest from it.”

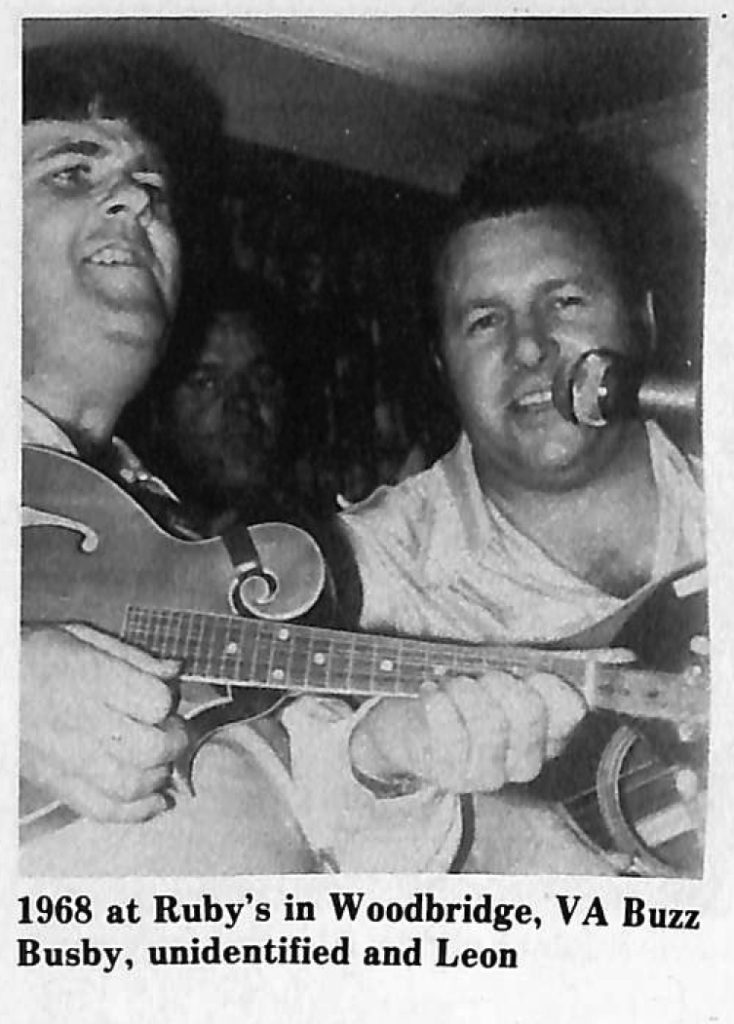

In 1968, Leon received a call from mandolinist Buzz Busby.

“Buzz asked me if I wanted to play some music. I said I would be interested if we could do it seriously and, you know, not fool around with it. He convinced me that it would be on a serious basis. So right away I went to work and found us a job at Ruby’s Restaurant in Woodbridge, Virginia, on Route 1.

“Buzz and I stayed together for about a year and a half. Then Wayne Yates replaced him.”

Numerous musicians played with Leon during this two and a half-year stint at Ruby’s, among them bassists Tom Gray, Ed Ferris and Bill Rawlings and banjoists Lamar Grier, Dick Drevo and this writer.

Over the course of their partnership, Leon and Buzz recorded material that eventually was released on two albums.

“When Buzz quit, we got together and had a business meeting to decide what to do with the stuff we’d recorded. Otis Woody, of World Records, had produced the sessions. Otis wanted to sell me one album or both. I visited Buzz, and he gave me a written OK to do what I wanted, and I bought both.”

“International Bluegrass,” on the Jessup label, was the first album released and Leon’s first, under his own name. It included several original compositions. In addition to Busby, sidemen were Lamar Grier and myself, banjo; Ed Ferris and Gary Henderson, bass, and Russ Hooper, Dobro.

Two years later, in 1972, Rounder records purchased the remaining material and released it as “Honkytonk Bluegrass,” with Leon and Buzz sharing equal billing. It featured close duet harmonies and showcased Busby’s mandolin style —soulful, often brilliant, occasionally hilarious—and contained some chilling Busby originals, including “At The End” and “I Stood On The Bridge At Midnight.”

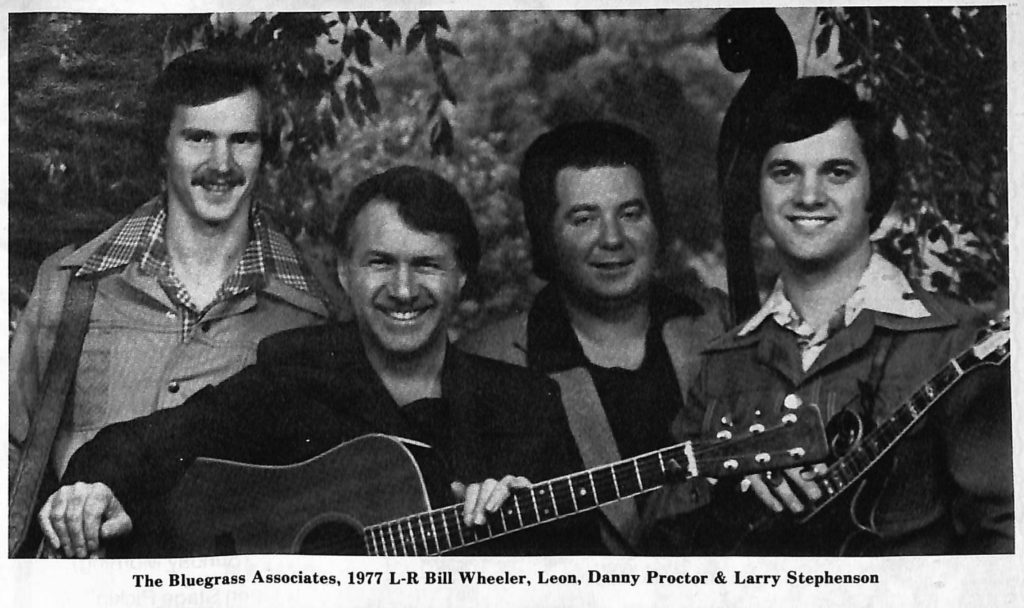

After the lengthy gig at Ruby’s, Leon decided to change his group’s name from the Bluegrass Association to the Bluegrass Associates. “‘Association’ made it sound like it was a company or a factory or something,” he said.

The first Bluegrass Associates were Bob Wilkerson, banjo; Ray Griffin, bass; and Roger Green, Smiley Hobbs and Frankie Short (in that order) on mandolin. A first album was released on the local Folly label, which later sold the masters to Country Records, the Canadian label with which Leon continues to record.

Further personnel changes occurred in 1976 when Leon recorded his next album, “Places and Friends I Once Knew,” with Billy Wheeler on banjo and Larry Stephenson on mandolin. Ray Griffin remained on bass, Mike Auldridge played Dobro and steel guitar and Gordon Smith played drums. The album contained three Morris originals in addition to the title cut, and represented a change from traditional bluegrass to a more contemporary approach.

In 1978, “Bluegrass Favorites”—a collection of warhorses old (“Foggy Mountain Breakdown”) and new (“Fox on the Run”) was released with yet another lineup; Billy Wheeler, banjo; Wayne Lanham, mandolin; Keith Rogers, electric bass; and Vic Mullen, fiddle.

In 1979, Leon recorded a gospel album, still in the can. Its title will be “Heaven is Waiting for You,” which he wrote along with several other spirituals.

Leon says his thought became focused on religion in 1975.

“It made me a bit more serious about life. Cliff Waldron by then [leader of one of the the first “newgrass” groups, the New Shades of Grass] used to go to a little church, the Southern Baptist Church, out near Manassas, Virginia, and I started going. Cliff had already been saved at this time, bless him, and I got saved out there too.

“I quit music for a little while and then went back into it. I don’t think there’s sin in that. I try to keep as clean and good as I can under the circumstances. I have God in mind all the time.”

In recent years Leon has been traveling frequently to Canada, allowing his local appearances to fall off.

“My dear old country’s been good to me. I wouldn’t move back—I’m settled here and have a painting business. It just happens that I can call up there and get the work and money to make the traveling worth-while. Which is hard, you know, in this business when you’re struggling.” Leon grins. “I get a lot of airplay in Canada and they really distribute my records.

“Bluegrass started to catch on up there six or seven years ago. Do you remember when the Country Gentlemen were at the Shamrock [a now-defunct Georgetown club] from in the mid ’60s? Well, that’s the way it is in Canada now, all over. They’re just turned on. Every time I go up there I sell out of every album I have.”

Do the audiences have certain preferences? “They love it all, they really do. I like to do both traditional and ‘uptown’ things. Maybe even a little country. I believe if you played a song backward they’d like it.

“I’ve got about five original numbers that I’m ready to record on the next album. As a matter of fact, I’m hoping that the next album will be 75 percent original stuff. I’m really excited about it.

“Over the years, I hope I’ve gotten better as a songwriter. I think I’ve come up with some pretty good material. I’ve got stuff that I’ve written that I just stick away in the closet and forget about, and there’s some stuff that I write that probably would be good for somebody else, but not for me, so I just put it aside.

“There’s one thing I’ve got to my advantage: I know that I’ve still got to learn. I know that I don’t know it all. If I get to the point where I think I do, I might as well quit. I know that if I keep that in mind, it’ll help me.”