Home > Articles > The Archives > Larry Sparks

Larry Sparks

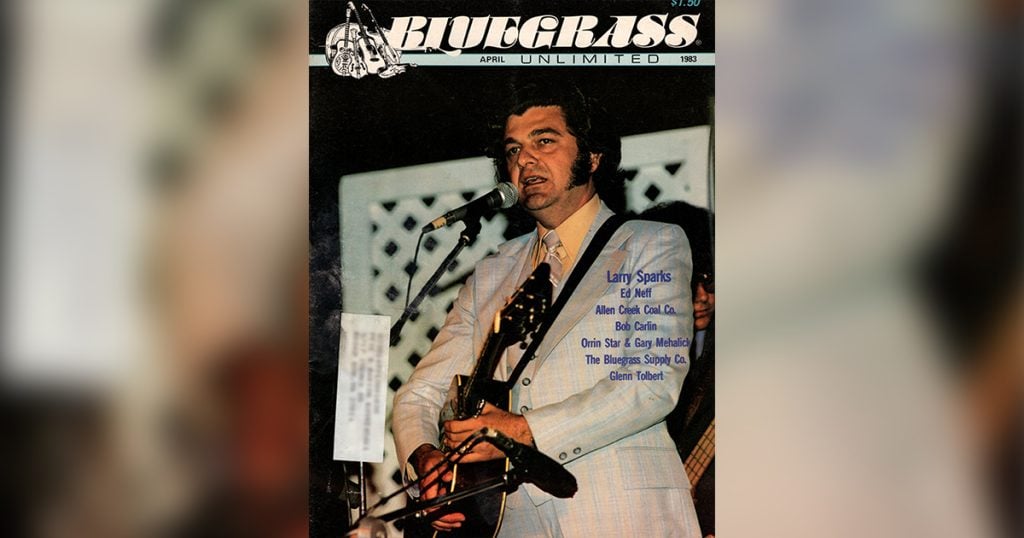

Reprinted From Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1983—Volume 17, Number 10

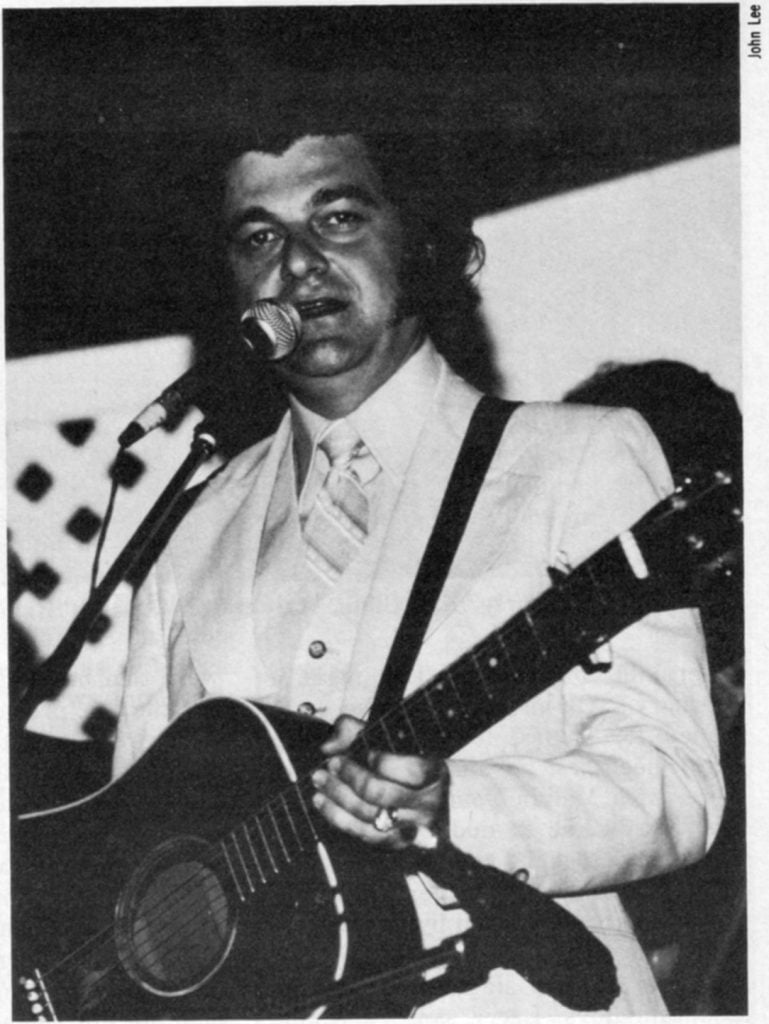

The Larry Sparks story begins September 25, 1947, in Lebanon, Ohio, just across the Kentucky line. Larry is the youngest of nine children of Eva and Charlie Sparks; all the children played guitar at least a little, and his grandfather Lewison Dose Russell was an old-time fiddler who won many contests in Jackson County, Kentucky. Although the Sparks home had no record player, Larry was listening to country music on the radio at an early age, and he began playing guitar with his sister Bernice when he was five years old. His daily walk to and from school took him past a restaurant that had country records on the juke box. Larry was drawn immediately to the singing of Hank Williams, and he began noticing something strongly different in the music of Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, and the other prominent original bluegrass stars. “I admire them all,” Larry says today, “(their music] sounded pure to me—I liked what I heard.”

Although his sister and his mother encouraged his musical inclinations, Larry doesn’t feel he was “pushed into anything. What I’ve accomplished so far, I really did it just on my own.” By the time he was ten, he began trying to play lead runs on the guitar. Almost immediately, he felt the need to develop his own guitar style, one that would be recognizable as his own after just a few notes. Lead guitar was just beginning to come to the fore in bluegrass music, so “back when I was learning to pick, there weren’t a lot of guitar pickers around, and I’m glad there weren’t. I think the best way for anybody to learn is to bring it out of yourself.” In his usual understated way, he must have been something of a prodigy, also learning the mandolin and honing his talents playing local area clubs as both leader and sideman. He recorded a single with the Slate Mountain Boys, playing guitar on one side and mandolin on the other. Wayne Raney’s nighttime country music programs on Cincinnati’s WCKY were also heightening Larry’s interest in the music.

Larry was still just sixteen when he took the first big step in what has become a long and illustrious career. The Stanley Brothers had been playing a great many shows in the Cincinnati-Dayton area, often with the noted area air personality, Paul “Moon” Mullins on fiddle. Paul had met Larry, and it was Paul Mullins who referred Larry Sparks to the Stanley Brothers. For the next two years, although he never recorded with them, Larry traveled part-time with the Stanleys, “alternating” with George Shuffler. He played his first date with them there in Ohio; later, he was with them when they played The University of Chicago, and traveled down into Virginia and North Carolina. Looking back on those days, Larry feels the personal encouragement he received from Carter and Ralph Stanley was all-important. “If I hadn’t worked with the Stanley Brothers, and (later) Ralph Stanley, it’s possible I might not even be in music today. Just being with the Stanley Brothers was exciting to me. They helped me get started, and they did a lot for me.”

Those two years also brought Larry into a firm friendship with the man who has been his strongest bluegrass singing influence, Carter Stanley. Larry remembers Carter as a highly sensitive, intelligent man, who gave freely of his time to talk with Larry, and who wanted to use Larry with the group as often as he could. “When I sing a song, I try to do what he did —live what you’re singing; I think that’s what you have to do.”

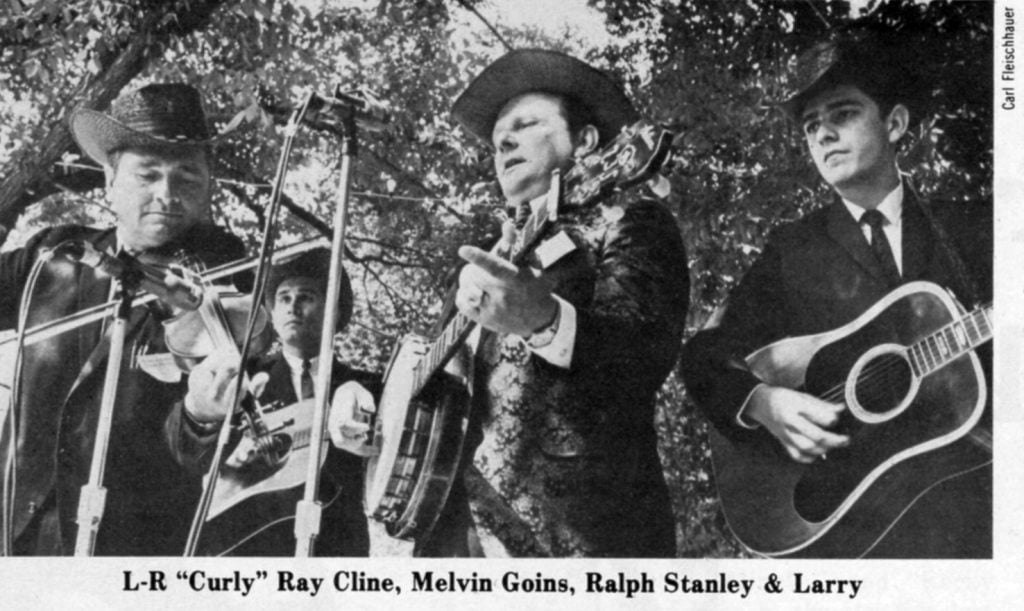

It was in 1965, during his stay with the Stanleys, that Larry recorded his first single under his own name for the Jalyn label in Dayton, Carter Stanley’s “It’s Never Too Late” and “Sandy Mountain Breakdown.” When Ralph Stanley reorganized the Clinch Mountain Boys after Carter’s death, and began playing shows again in February, 1967, it might seem only natural in retrospect that Larry Sparks become his lead singer. That is exactly what happened, but in a slightly unexpected way. Larry heard that Ralph was going to play his first show at Tom’s Tavern in Dayton, on the night of February 7. On his own initiative, Larry headed for Tom’s, feeling that Ralph might need a lead singer. Ralph was there, with Melvin Goins on guitar and Curly Ray Cline on fiddle. There was a house band, too, and anyone could get up on stage and sing with them. Ironically, that house band was led by the late Roy Lee Centers, who would become Larry’s successor as lead singer in the Clinch Mountain Boys. Larry sang “a couple” with the house band, and Ralph sent word that he wanted to talk with him. “I got the job, probably around midnight,” Larry recalls, with obvious delight. He doesn’t seem displeased that Ralph didn’t automatically think of him as Carter’s replacement; Ralph hadn’t heard him sing lead much at all, and not that much baritone, since fiddler Red Stanley often sang that part with the Stanleys. But Larry had been practicing his singing at home, and the experience paid off. For the next three years, while still a very young man filling a very big pair of shoes, he was the lead singer for Ralph Stanley’s Clinch Mountain Boys.

Even before joining the Stanley Brothers, Larry had thought of someday forming his own group. In the fall of 1969, “I felt I was brave enough to give it a try.” A phone call from Ralph started him out on his own. “We parted good friends,” Larry remembers, “I’m glad we did. Ralph has done a lot for me. I think if you leave a group, it’s best to leave as friends.” Playing clubs for a while, Larry formed the first Lonesome Ramblers in November, with his sister Bernice on rhythm guitar, Joe Isaacs on banjo, David Cox on mandolin and Lloyd Hensley on bass. (Isaacs, who sings like Carter and picks like Ralph, helped give the band a strong Stanley flavor.)

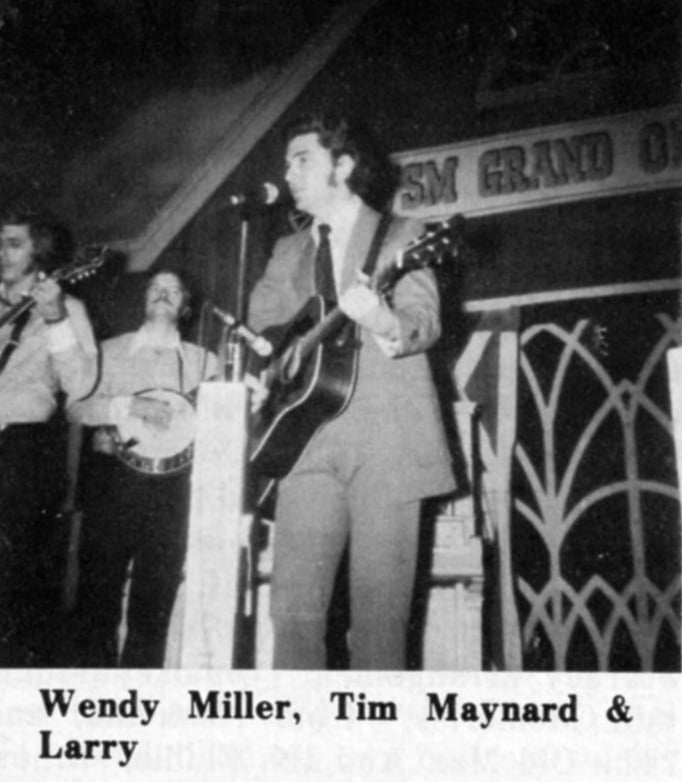

An intensely thoughtful Larry Sparks peered out from the cover of his first Pine Tree LP, “Ramblin’ Guitar,” recorded soon after the band was formed. “Too fast,” he says, with refreshing candor. Fairly soon thereafter, the second Pine Tree LP, “New Gospel Songs,” appeared. “When I got as far as the gospel album, I knew I was going to have to make more of a change, to develop my own style.” It was then that Mike Lilly on banjo and Wendy Miller on mandolin, both recruited from local club work in Dayton, made their first appearance in the group. Over the next four years (minus the time Lilly spent with the Country Gentlemen), Mike and Wendy played an important part in helping Larry establish what became his own distinctive sound; in the process, they themselves became “celebrity sidemen.” Four of the new songs on the gospel album were the work of Osborn Thorpe, who had also produced and written two songs for the first album. Thorpe is a deputy sheriff by trade, pursuing his songwriting abilities only as a hobby, yet his “Green Pastures In The Sky” became Sparks’ first hit. During 1971, Larry began recording for Old Homestead. “Bluegrass Old & New” had several Sparks originals bringing to nine the number of new songs written by Larry and/or his sister Bernice for his three albums. And the group cut their two Pine Tree singles (now on an Old Homestead LP) the same year.

By 1972, Larry’s career was on the upswing. He was working regularly in clubs, and he had begun to appear at an increasing number of top bluegrass festivals. His records, although they suffered from spotty sound quality and/or limited distribution, were helping him become more widely known. Then came what should have been a significant boost for him. Longtime bluegrass supporter and Stanley Brothers fan club president, Fay McGinnis, helped Larry secure a contract with Starday Records. With the dependable Art Wydner now the group’s bass player, “Ramblin’ Bluegrass” was a powerful mixture of Sparks’ originals (many written with Bernice), country and bluegrass standards, and two fine instrumentals. The album was well produced, well distributed, and a single from it was sent to radio stations to promote airplay. But, within the year, Starday developed financial difficulties, and suddenly, Larry’s best new material was unavailable on record. (An intriguing sidelight to his Starday recording sessions was the thirteenth song recorded, a cut that has never been issued. Starday had commissioned a black songwriter named Charles Brown to write a song for Larry; Brown listened to him sing and returned the next day with “You Could Have Called,” for which he provided rolling, low-key piano background on the recording.)

Larry waited as long as he could for the Starday album to again be available. He knew that no matter what, he would have to have the songs he was performing on stage available on record for the 1974 festival season. So, in quick succession, he cut a gospel album for Old Homestead, “Where The Sweet Waters Flow,” then “The Lonesome Sounds” for Old Homestead and his first King Bluegrass LP, “The Footsteps Of Tradition.” By this time, Joe Meadows had checked in as the Lonesome Ramblers first full-time fiddler, and first Tim Maynard, then Dave Evans replaced Mike Lilly on banjo. Meadows and Evans changed the complexion of the Ramblers’ sound somewhat, their smooth fiddling and hard tenor-singing, respectively, making the band more reminiscent of Bill Monroe’s latter-day Blue Grass Boys. “The Lonesome Sounds” LP featured Larry’s version of another of his most popular songs, “Going Up Home (To Live In Green Pastures).” While working with Ralph Stanley and living in Clintwood, Virginia, Larry heard it sung by the Abingdon, Virginia-based Chestnut Grove Quartet, and remembered it from his first gospel LP with Ralph. Larry had learned that by recording for several companies, he could have more records issued more quickly, so very soon, there was a second King Bluegrass LP, “Sparklin’ Bluegrass,” without Joe Meadows, who had gone on to Jim & Jesse, but with Lilly back. Larry had another hit with “A Face In The Crowd,” written by two men from Haysi, Virginia, near the Stanley homeplace, Dean St. Clair and Henry Smith. Just before Evans and Meadows departed, they helped Larry record his “Pickin’ & Singin’ ” LP for Pine Tree, which included an improved version of “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain,” awhile before it became a country hit in 1975. Still another of Sparks’ best songs came out in Larry’s next Old Homestead gospel LP, “Thank You Lord,” which has also been a much-requested song. Aspiring songwriters have always sent popular performers their songs, and every so often there is a jewel among them —in this case, ‘I’ve Just Seen The Rock Of Ages,” from John Preston, then and now a penitentiary inmate.

By all signs, Larry Sparks’ career was accelerating by 1975. He was playing more major festivals, more auditoriums and larger halls, and when he played clubs, they were less likely to be the war zones where many performers start out. In general, he was receiving more, and more widespread, recognition. It was time for a quantum leap, and this was accomplished in the King Bluegrass LP, “You Could Have Called.” In the past, each of Larry’s albums had been a group of generally superior performances melded into a homogeneous unit; here, the title tune, patterned after the original Starday arrangement, “Smokey Mountain Memories,” from Nashville, and “The Old Man And His Fiddle,” a new song, co-written by Bernie Faulkner, who also wrote “Black Diamonds” for Bill Harrell and “The Testing Times,” an old song, both learned from people in eastern Kentucky, leaped out of the album demanding individual attention. Although he had used some overdubbing on past albums, this was the first one handcrafted piece by piece. For the first time, he used a Dobro player, Tommy Boyd, who would stay with him, doubling on banjo, for the next five years. Larry had always preferred to use his regular sidemen on his recording sessions, so that he could closely reproduce his recorded sound on stage, but here, for the first time, he used a guest sideman, Ricky Skaggs, whose triple-fiddle work added an extra fullness to the increased depth and maturity of Larry’s own singing.

If the “You Could Have Called” LP was an immediate success, his first concept album, the 1977 LP of Hank Williams songs, took a bit longer to establish itself. Featuring the fiddle of Chubby Wise, its appeal is low-key and subtle; after “You Could Have Called,” it may have seemed somewhat anti-climactic. Ironically, the project was probably dearer to Larry’s heart and even closer to his soul. At first, Larry thought the album should have had more banjo; now, he feels it probably shouldn’t have had any banjo at all. Larry steered away from Williams’ big hits, because he didn’t want to do full-production numbers. Rather, he felt his own lonesome singing style would be most comfortable with the songs Hank had recorded privately, with just his guitar as accompaniment, some of which Larry had already recorded in other albums. “To me,” Larry said, “that was the best stuff he ever did.”

His next stop, Rebel Records, caused Larry’s old nemesis—a record company that wouldn’t put out his records—to reappear. The “John Deere Tractor” LP lay unissued for more than two years, before finally appearing after Rebel changed ownership. In desperation, Larry formed his own record company and re-recorded four of the songs from “John Deere Tractor” on his Lesco LP, “Kinda Lonesome,” only to have the two albums come out within a few months of each other. Again, Larry demonstrated his consistency in the face of changing personnel; the subtle finesse of Kirk Brandenberger’s fiddle on the Rebel set had given way to the Lesco LP to the more dynamic, southwestern-tinged fiddling of Glen Duncan, who stayed with the Lonesome Ramblers long enough to also record the June Appal LP, “It’s Never Too Late.” Displaying increased versatility, Larry played banjo for the first time on record on the June Appal set, overdubbed his own baritone vocals on the “John Deere” LP, and played mandolin on record for the first time since he dubbed in the mandolin part on Charlie Moore’s 1975 Old Homestead cut of “Remember Me.” Continuing his penchant for finding some of his best songs in some of the unlikeliest places, Larry found “The John Deere Tractor” among demo tapes that had been languishing at Lemco Recording Studio in Lexington, Kentucky. A writer who is known to have written several other fine songs, but whose name had eluded recall, sent the song to Lemco, where it lay for several years. J.D. Crowe had listened to the song, recognized its quality, but elected not to use it when Larry happened across it and made it one of his most requested songs. (Editor’s note: After much research, with the help of J.D. Miller of Lemco Studios in Lexington, Kentucky the writer of “John Deere Tractor” has been uncovered—Lawrence Hammond—though Larry Sparks drastically rearranged the tune prior to recording it)

For the past eighteen years, Larry Sparks has charted a remarkably surefooted, deliberate course, one that has brought him to the verge of superstardom in bluegrass music. His music has grown in scope and in depth, but has never grown away from, or turned its back on, where it has been. Although only thirty-five, Larry approaches his career like many of the first-generation bluegrass stars he initially admired, but without finding it necessary to adopt either the abrasive bravado or the gnarled aloofness of several of the veteran bluegrass stars. Without the fanfare attendant upon the more flamboyant bluegrass personalities, Larry and his Lonesome Ramblers have played most of the major bluegrass festivals (Bean Blossom, Lavonia, Stanley Memorial, Berkshire Mountains, etc.), plus the WSM Fan Fair in Nashville, the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, and in more than forty states and Canada on a schedule that keeps the band working at least two hundred days a year. Unlike many musicians his age, Larry is a first-generation style band leader. He realizes that the extent of his continued success depends primarily on him, and by both necessity and choice, he is very much the captain of his own ship. Through the Lonesome Ramblers have passed bluegrass musicians of all persuasions. Have any of them tried to overwhelm his style, or urge it in a different direction? “Oh, sure,” says Larry, matter-of-factly, in a way that conclusively indicates that none has succeeded. Musicians seem to be passing through the group at a faster rate—none of the musicians who recorded what is at press time still his latest LP, the Acoustic Revival “Ramblin’ Letters” in February, 1981, was a member of his traveling band that same July —without in any way affecting the consistency of his artistry. Larry has recorded and traveled with and without fiddle, with and without mandolin, with and without Dobro, and even (when Tommy Boyd was playing Dobro) without banjo, without affecting Larry’s overall style and impact. (Larry removed some of the urgent insistency he needed to match Ralph Stanley’s tenor from his voice when he went on his own, in favor of his more personal, mellow approach, one that was no less powerful.) By 1974, he felt that he could execute on the guitar anything his creativity could come up with, so, if there had been any obstacles to his untrammeled artistic growth, they were no longer there.

Most artists whose work has been dubbed “lonesome” have been personalities with strong internal, often self-destructive, conflict. Larry Sparks, on the other hand, seems to get along with himself very well. (Significantly, the Hank Williams songs Larry likes best are those where he was in one sense of the most lonesome, being without his band, but also the most free from pressures and conflicts.) Maybe that’s why, after an already long career (“I’ve been through the mill,” he says with a grin), he’s in such good shape, both personally and professionally. Although he’d like to find “just the right” fiddler, he’s pleased with his current band —John Masters on banjo, Jim Heffernan on Dobro and his son Larry D. Sparks on bass. Both his problems with record companies and his own developing artistry have caused him to record about thirty of his songs twice, providing an unusually clear comparative picture of his musical maturation through the years. And, now that Old Homestead has reissued all his Pine Tree material, almost all his recordings are still available. Six gospel songs from King Bluegrass have been combined with six newly-recorded sacred songs for an album on Rebel due out soon. Although he is not a prisoner of his hits, Larry has his share of songs that have become “demand” numbers at personal appearances: “A Face In The Crowd,” “I’ve Just Seen The Rock Of Ages,” Allen Mills’ “Love Of The Mountains” (in both the Rebel and Lesco LPs), “You Could Have Called,” “Smokey Mountain Memories,” “Carter’s Blues,” and many of the songs he has written himself.

Larry Sparks stands poised for the superstardom he so richly deserves. Ahead, a probable guitar instrumental album, possibly a blues album, more personal appearances in more places, and more of the creativity that hasn’t stopped for twenty years. For now, Larry can take pride in the fact that he is at the forefront of bluegrass music, the favorite performer of as many fans as anyone in the business today. His music is independent of classification, although it touches traditional, contemporary, and even occasionally progressive bluegrass. With his own unique, quiet dynamism, Larry Sparks hasn’t found his niche—he’s made his own.