Home > Articles > The Archives > Josh Graves—Dobro Virtuoso

Josh Graves—Dobro Virtuoso

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1982, Volume 17, Number 1

He is popular with the people. He will talk to them for hours.” A bluegrass festival promoter is speaking.

“He has alot of friends,” comments a popular bluegrass musician.

“He’s a very versatile musician. He plays more instruments than most people know about.” So says a veteran bluegrass festival emcee.

“I still consider him the best Dobro player around,” declares a long time fan of bluegrass music.

These are the responses elicited from persons associated with bluegrass music when asked the question, “What do you think of Josh Graves?”

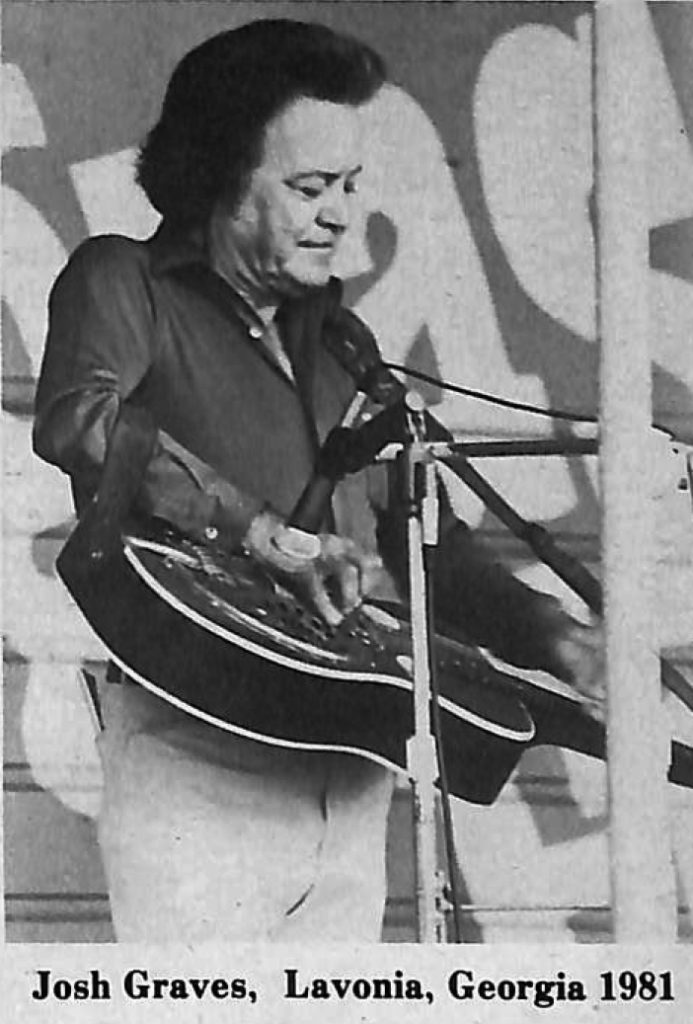

On a hot July afternoon on the banks of Shoal Creek, that flows behind the bluegrass festival stage at Lavonia, Georgia, Josh, who is also called Buck, Graves reflects on these and other things that have been said about him and his music and shared some of the varied experiences that have been his during more than forty years as a professional musician.

“I was born in east Tennessee — Tellico Plains in Monroe County in the foothills of the Smokies,” he begins. The date was September 27, 1928 and his parents named him Burkett. This name, however, would not long survive as the one to which he would answer. The daring nature of a growing boy, a mother’s wrath, and a neighbor’s wit would see to that.

“When I was just a little boy,” Josh explains, “we had this wild pony, and mother told me to stay off of him. But one Sunday morning I slipped out the window and tried to ride him. Just about the time I threw my leg over his back, mother cut down on me with a hickory switch. A neighbor who lived across the creek saw what was going on and yelled ‘Look at Buck Jones,’ and the name ‘Buck’ has stuck with me ever since.”

When it comes to nicknames, Burkett Graves is twice blessed. The other sobriquet by which he is equally well known derives from the early days of his career when he was billed as Uncle Josh in the comedy team of Uncle Josh and Aunt Jeroshia. Later, he would revive the name and play Uncle Josh against Jake Tullock’s role as Cousin Jake.

Josh’s father, who was a blacksmith, played harmonica, and his wife played the organ. There were many other musicians in the family, but Josh points out that none of them took their music seriously except himself.

“Once a month my daddy would give a party,” Josh continues, as he talks about his childhood which was spent near Maryville, Tennessee, located some thirty miles northeast of Tellico Plains. To provide entertainment at these parties his father would hire two black musicians. “One played the little old tater bug mandolin, and one played a guitar,” Josh recalls. “And I sat right at their feet and listened to them play. They played the blues. I guess that’s one thing that inspired me to want to play. The first instrument Josh tried to master was the five-string banjo. “But I couldn’t play the thing,” he admits. “I had an uncle who had a banjo, and I tried and tried to learn to play it, but I found out my little old hands were so short I couldn’t make the chords. Then I put a clothes pin up under the strings at the top of the neck and got me a table knife and started playing it like a Dobro.”

Josh’s interest in the Dobro sound was inspired by the playing of Cliff Carlisle whom he had been listening to on the radio and on Jimmie Rodgers recordings. “Cliff turned me on to that thing,” he asserts. “And when I was nine years old I went to hear him when he played at Wildwood, Tennessee. After the show he was talking to some men, and I was just standing there looking at him. But he had enough time to come over and talk to me, and that really impressed me. Cliff lives up in Lexington, Kentucky, now. I see him once in a while, God love him. I hope he lives to be two-hundred years old.”

A little later Josh acquired a National Dobro. “One of those old metal jobs,” he explains, “that would break your back, and they still will.”

Josh obtained his first significant job as a professional musician at the age of fourteen. “I took that old National and went to Knoxville and went to work for Cas Walker, bless his heart, at WROL. Cas paid about sixty bucks a week for a group. I’d go back home with a roll of money in my pocket, and they thought I was a whiz. They would listen to me on the radio, and I’d dedicate them a tune, you know. I thought I was tough.”

In Knoxville Josh played with Esco Hankins’ band. “He sang like Roy Acuff,” Josh explains, “and he’d say, ‘Play like Oswald.’ But I wouldn’t do that. No sir. I love Oz, and there’s nobody going to touch him on what he does, but I’ve got to play my way or I can’t play. Esco got a little mad at me for that.” Josh was with Hankins, off and on, from 1943 until 1950, performing with him, not only in Knoxville, but in Rome, Georgia, and Lexington, Kentucky.

During his off periods with Hankins, Josh worked some with country artist Jack Greene and for a while even quit the music business altogether to take a job as a construction worker. Around 1950, he replaced Bill Carver as Dobro player with Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper who were appearing on the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia. His four-year stint with the Coopers gave Josh his widest exposure up to that time because of WWVA’s extensive listening area which reached well into Canada.

“Stoney Cooper taught me more about show business than anybody,” Josh reminisces. “He was a gentleman, and I was as wild as a guinea —twenty-two years old. They’d take me to the hotel every night and walk me to my room. I’d say good night to them and then go down the fire escape going to a party. I guess I was a problem child. But Stoney tried to look out for me. He bought me clothes, and I called him Pappy. I loved him so much. He’s dead now and gone, but that memory never dies.

“Wilma Lee was a fine lady. She still is. She was the one I was afraid of. She kept an eye over the group, and I guess that was good back in those days.”

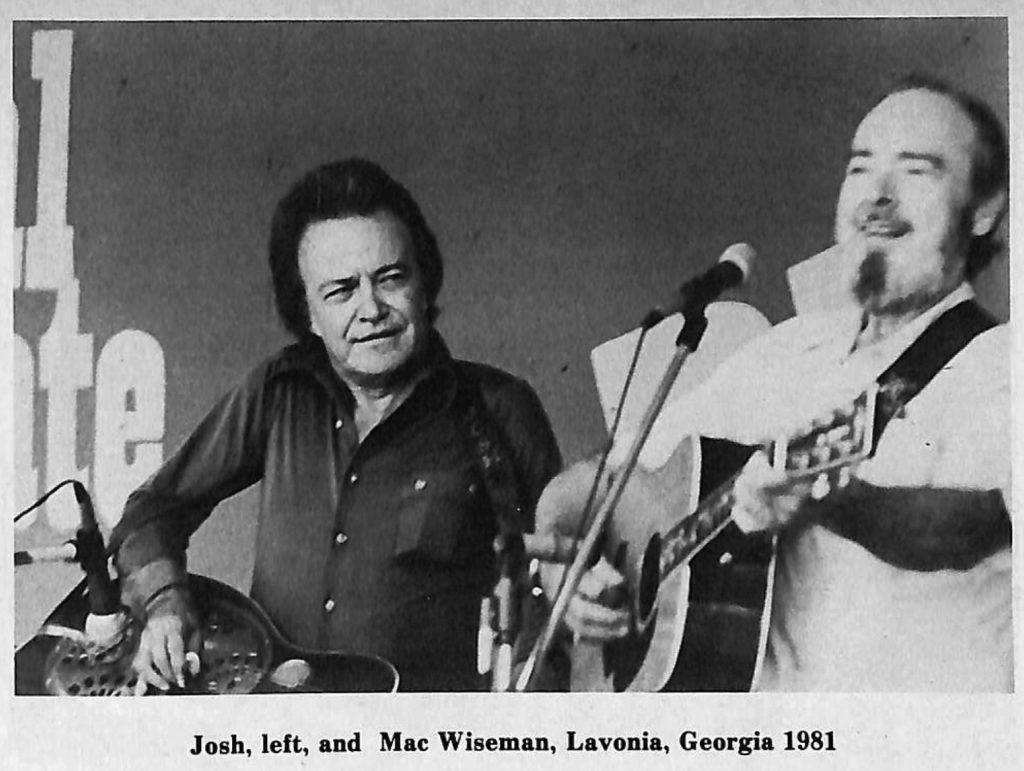

It was around 1949 that Josh first met Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs who, at the time, were based in Lexington, Kentucky. That was when, according to Josh, he learned “to like the stuff they were doing.” It was not until May 14, 1955, however, that he became a member of the Foggy Mountain Boys, following a brief period with Mac Wiseman. Josh remained with Flatt and Scruggs until their split in 1969, sharing in the varied trials and triumphs that this duo experienced during those fourteen years. Josh once told writer George Martin (BU-Dec. 1972) of the Foggy Mountain Boys’ harried schedule as they hopped, skipped, and jumped across the country to fill stage, television, and Grand Ole Opry commitments. “I didn’t have a day off for six months when I came with Flatt and Scruggs,” he said.

Josh was with Flatt and Scruggs while bluegrass history was being made: when the Martha White Flour commercial became a national hit; when Flatt and Scruggs got caught up in the folk music boom with appearances at the Newport Folk Festival and the release of such albums as “Folk Songs of Our Land” and “Hard Travelin’” when the Foggy Mountain Boys played at Carnegie Hall; when countless millions of television viewers and movie goers were introduced to bluegrass music through “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” and the theme music of “Bonnie and Clyde.”

When Josh went to work with Flatt and Scruggs (as a bass player incidentally), for all he knew, he would be with them for only fourteen days. He never dreamed they would keep him fourteen years. “They said, ‘Come down and try out for two weeks,’ ” Josh recalls. “ ‘If we like you, and you like us, you’ve got a job.’ Well, two weeks went by, and they called me in. I thought they were fixing to send me home. But they said, ‘Which had you rather play, the Dobro or the bass?’ And I said, “Man, are you giving me a choice?’ ”

As is now well known, Josh opted for the Dobro, and he’s not sorry. Of his fourteen-year tour of duty with Flatt and Scruggs he says, “I enjoyed it; really, I did. I’m going to tell you something about those boys,” he continues. “If they said, ‘I’ll meet you in the morning at nine o’clock out there in front of your mail box,’ you could count on that. And you never had to go looking for your money. They’d bring it to you.”

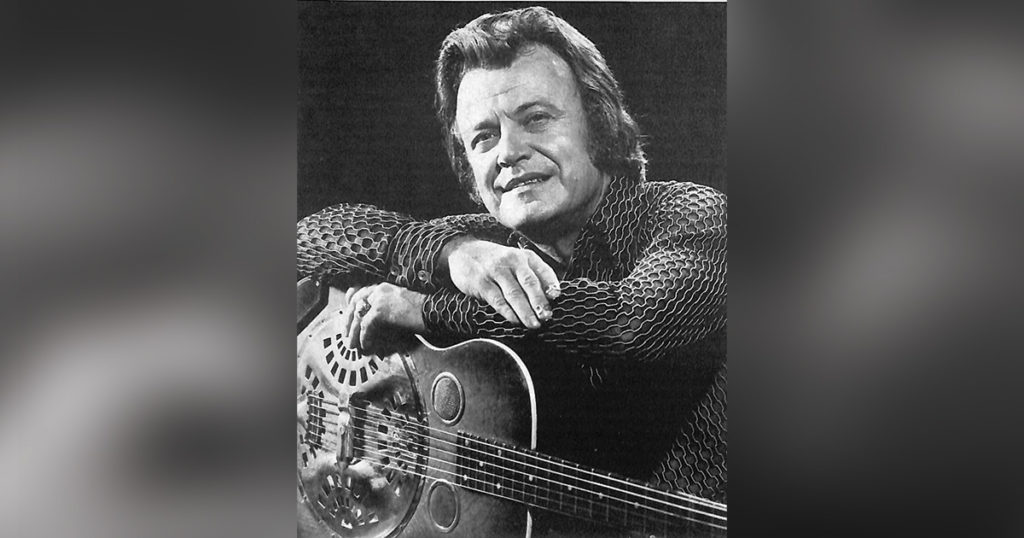

In his book, Old As the Hills, Steven D. Price states that the unamplified steel guitar had not been associated with bluegrass music prior to Josh’s appearance as a member of the Foggy Mountain Boys. He goes on to say that Josh “turned the Dobro into a powerful lead voice, slipping and swooping like a barnstorming biplane” and credits him with inspiring many young musicians, notably Jerry Douglas, and for contributing to the decision of the Dobro Company, which had stopped manufacturing the instrument, to resume production in 1956. Another Dobro player who acknowledges his debt to Josh Graves is Mike Auldridge who says that the way he learned to play the instrument was by slowing down the Flatt and Scruggs records that featured Josh.

Another bluegrass historian, Bob Artis, writes in his book, Bluegrass, that Josh’s inclusion in the (Flatt and Scruggs) band resulted in a shift from the hard bluegrass sound, as heard on pre-Dobro songs like ‘I’ll Go Steppin’ Too’ and ‘Thinkin About You,’ to a softer, hillbilly sound on such numbers as ‘On My Mind’ and ‘Some Old Day.’ ”

“I believe I can explain that,” Josh responds. “What they wanted to do was to get away from the Monroe sound. They wanted a little something different, and they came out with ‘On My Mind’ and ‘Randy Lynn Rag.’ ”

When Flatt and Scruggs split in 1969, Josh, along with Paul Warren and Jake Tullock, remained with Flatt to become the Nashville Grass and to return to a more traditional bluegrass sound.

According to bluegrass historian Neil V. Rosenberg, bluegrass fans who earlier had expressed “dismay at the Nashville sound of the recordings and of their disappointment at live shows [of the Foggy Mountain Boys during their last three years of existence]” were soon writing enthusiastic letters to the bluegrass journals rejoicing that “Lester’s [Nashville Grass] sound was the good old traditional bluegrass sound.”

After two years with Flatt and the Nashville Grass, Josh joined the Earl Scruggs Review where he stayed for another two years. “I loved every one of those boys —Gary, Randy and Stevie —and I still do,” Josh confesses. “But, you know, if you play acoustic guitar, like I have to do,” he continues, “and I won’t change it, and I never will. I couldn’t see myself putting a pickup on it. Though I know the money was good, but your heart’s not there, you know. I love Earl Scruggs. He taught me a lot of things. I just figured if there was some money out there, I was going after it. Sounds blunt, but be your own boss. Do what the heck you want to do. That’s what I had to do.” And so Josh Graves, after two years, left the Earl Scruggs Review. “In 1974, I broke out on my own, and that’s where I’m at today,” he says in summary.

Before Josh became acquainted with Earl Scruggs, he played the Dobro with his thumb and index finger, in the manner of his childhood idol, Cliff Carlisle. “But when I met Earl Scruggs, I changed it all. He taught me the three-finger roll. That man is a genius,” Josh extols. “He sat and worked with me like I was his brother.” As a result of Scruggs’ instruction, his banjo style was adapted to the Dobro; and in writer George Martin’s opinion, “the Dopera Brothers’ resophonic guitar probably has reached its greatest success in the capable hands of” his willing student.

Josh’s right-hand technique is not all he learned from Earl Scruggs. “My timing—” he explains, “Scruggs taught me that. If you hear me out there —I don’t care who I’m with —if it comes down wrong, I’ll come down with them. If they do it wrong, I’ll do it wrong with them. It doesn’t disrupt what they’re doing. You’ve got to learn to adjust to it.

“There are a lot of banjo pickers,” Josh continues, “but there’ll never be another Scruggs. If it hadn’t been for him, I guess I’d be back in east Tennessee hoeing corn. I almost got in a fight [at one festival] over him. This guy was putting Earl down, and I can’t stand that.”

When you hear Josh on the stage these days he most likely will be playing his R. Q. Jones guitar. However, he owns two vintage instruments, including a 1929 Dobro which he obtained early in his career for eight dollars. He says that the older instruments, which he played when he was with Flatt and Scruggs, will never be played again. “I raised a family with them, and I just laid them down. I might lose them —I did one time, but I got them back—so I won’t take them out again.

“I name my guitars,” Josh observes. “I have one named Julie, and the 1929 model is Cliff—after Cliff Carlisle. The one I’m playing right now is Elbert. I named him after a friend of mine in Kentucky. You know, after a while, your instruments get to be like your friends. The name Julie, Josh hastens to explain, was inspired, not by a woman he ever knew, but by an acquaintance who owned a gun by the same name.

After having used Gibson strings for a long time, Josh now uses GHS strings. “As hard as I play, for the front two strings, I like eighteens (.018”),” he notes. “I put a twenty-six (.026”) on the third and thirty-six (.036″), forty-six (.046”), and fifty-six (.056”) on the fourth, fifth, and sixth. Most kids will say, ‘Give us a fourteen or a sixteen on the first two strings.’ But the way I came up, working behind Flatt and Scruggs, I learned that you had better come drawed back with something. If you put a fourteen on the front, you’ll never be heard.”

For his picks, Josh prefers a National thumb pick and Dunlop finger picks. He likes a thumb pick “as big as you can get it.” He uses a Stevens bar.

Although Josh is best known for his Dobro playing, he is also an accomplished flat–top guitarist, and his stage shows usually feature a couple of solos on that instrument. Josh is also a composer of considerable merit and can boast of almost fifty BMI-licensed songs with his name listed as composer or co-composer. His first recorded song was “World of Sorrow” on the Mercury label. In 1959 he received a BMI award for “Come Walk With Me” which was recorded by Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper. “I wrote that song for Benny Martin, but it didn’t come down that way. He didn’t cut it. Wilma Lee and Stoney picked it up —I’m glad they did —and Benny played the fiddle on it,” he remarks with irony. Other compositions from Josh’s pen, either alone or in collaboration with others, particularly his friend, Jake Lambert, include the well-known, “Evalina,” “Roustabout,” and “The Good Things Outweight the Bad.”

A reviewer of Josh’s recent album, “King of the Dobro,” notes the presence of “some extraneous sounds … such as clarinet and drums.”

“Oh, I get cut up a lot of times,” Josh concedes. “I have about ten albums out now, and maybe I’ll use a pedal steel one time, and maybe a snare drum. When I do that I’m trying to get a play on the radio stations. You know —and I know —that at the radio stations, when they hear a banjo on a record they’re not going to play it. I don’t mean to offend anybody; I’m not trying to get above my ’grass people, but “King of the Dobro” is playing on a lot of stations. If it was strictly ‘grass it wouldn’t get that play.”

Josh has a large following in Canada, especially in the Ottawa Valley area where he usually plays the club circuit during the winter months. He notes that his recording of “Maiden’s Prayer” from the “King of the Dobro” album has received a considerable amount of air play in Ottawa.

Josh and his wife, Evelyn, were married in 1945. “She’s been an inspiration to me,” he says. “She’s stood by me in the good times and the bad times, and I love her for that.” The Graves have four children, three boys and a girl. The oldest son is a policeman in Hendersonville, Tennessee, and the second is a country music artist who records for CMH under the name of Billy Troy. The youngest son, Brian, still in his teens, is also a musician with leanings toward rock. The daughter, who is married and has three children, lives in Madison, Tennessee.

Looking back on his long career, Josh expresses the hope that he has “helped somebody down the road.” When he hears it said that his style has been copied, he considers it an honor. “I just hope that I’ve done something out there that the young people will enjoy. If I’ve done anything that they like— if I’ve helped in some way —that’s my reward.” With these words, Josh uncases his Dobro and heads for the festival stage. It’s about time for his second set of the day to begin. At the same time, a nine- year-old boy from Atlanta, with parents in tow, works his way to a front row seat where he sits in rapt attention watching every move of Josh’s hands as he plays such tunes as the mournful “Rosewood Casket,” the rambunctious “Shuckin’ the Corn,” and that chestnut among country tunes, “The Great Speckled Bird.” If Josh notices this young admirer, perhaps his mind wanders back forty-four years to that memorable day in Wildwood, Tennessee, when another nine-year-old boy stood in awe of a great Dobro player.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

When I was 10-12 years old I’d watch the weekly bluegrass show, live from a Huntington, WVA television station, maybe WSAZ. I enjoyed everyone’s professionalism in these live performances but none more than “Uncle Josh” and his bluesy Dobro playing. He always came across as a kind person who genuinely got a huge kick out of playing each of his parts on the band’s set list. Then in 1988 when I lived in Vienna, Austria for a time I was pretty homesick for my home in Floyd County in the Kentucky Cumberlands (just another homesick hillbilly, I guess). One evening I turned on the TV to the Sky Network probably and here was Uncle Josh on German television playing alongside Kenny Baker, a legendary fiddler from Elkhorn City, a tiny town in a neighboring county to mine. I was so delighted I sat there in disbelief and found tears in my eyes. Thanks so much for this excellent article.