Home > Articles > The Archives > Johnny Whisnant: Musical History

Johnny Whisnant: Musical History

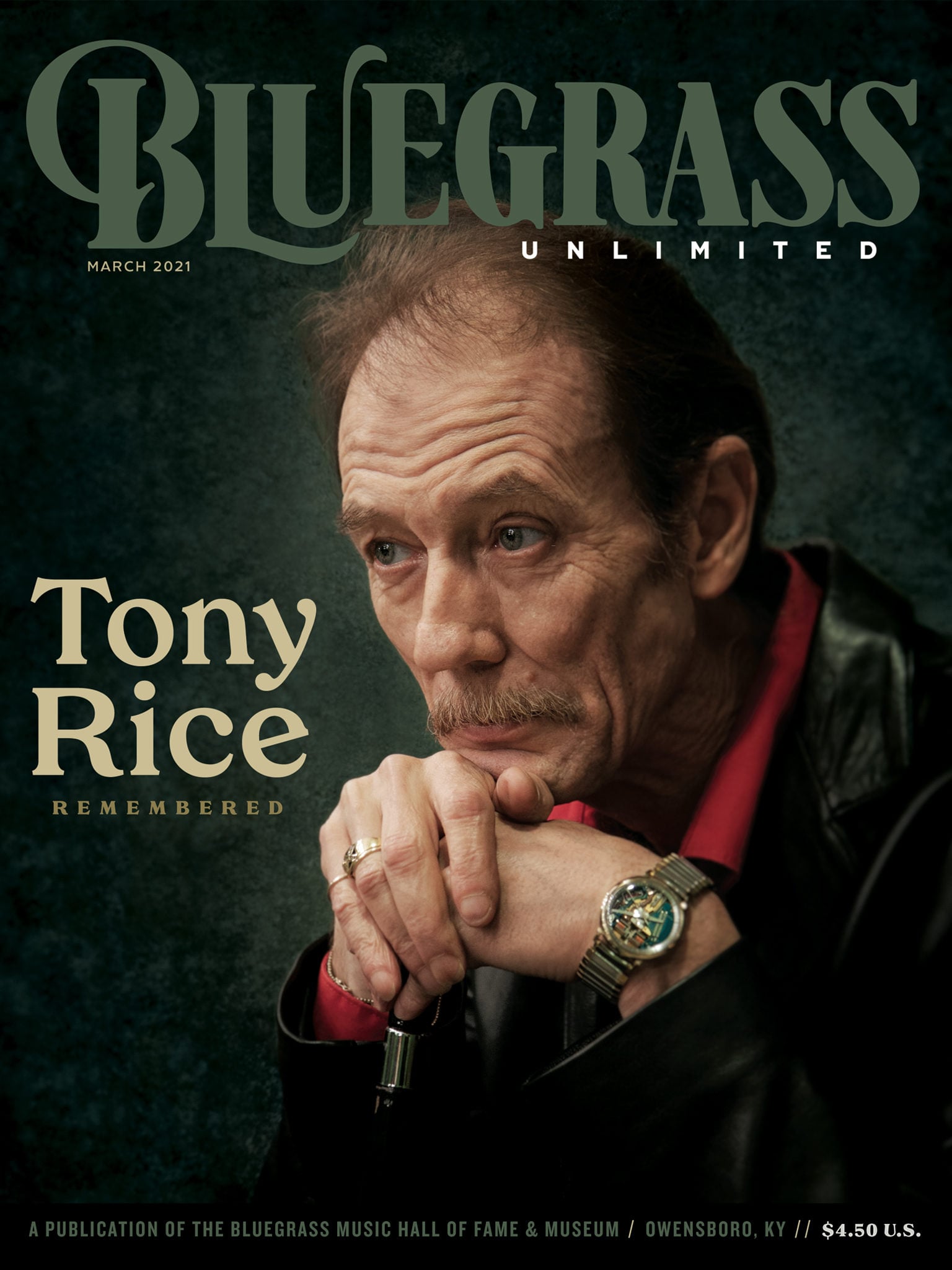

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

Part I

June 1970, Volume 4, Number 12

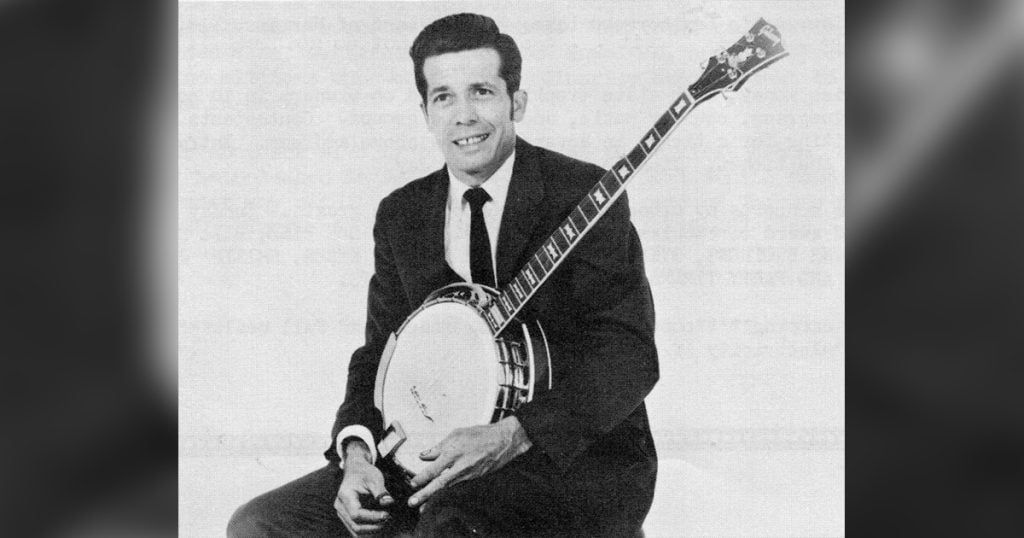

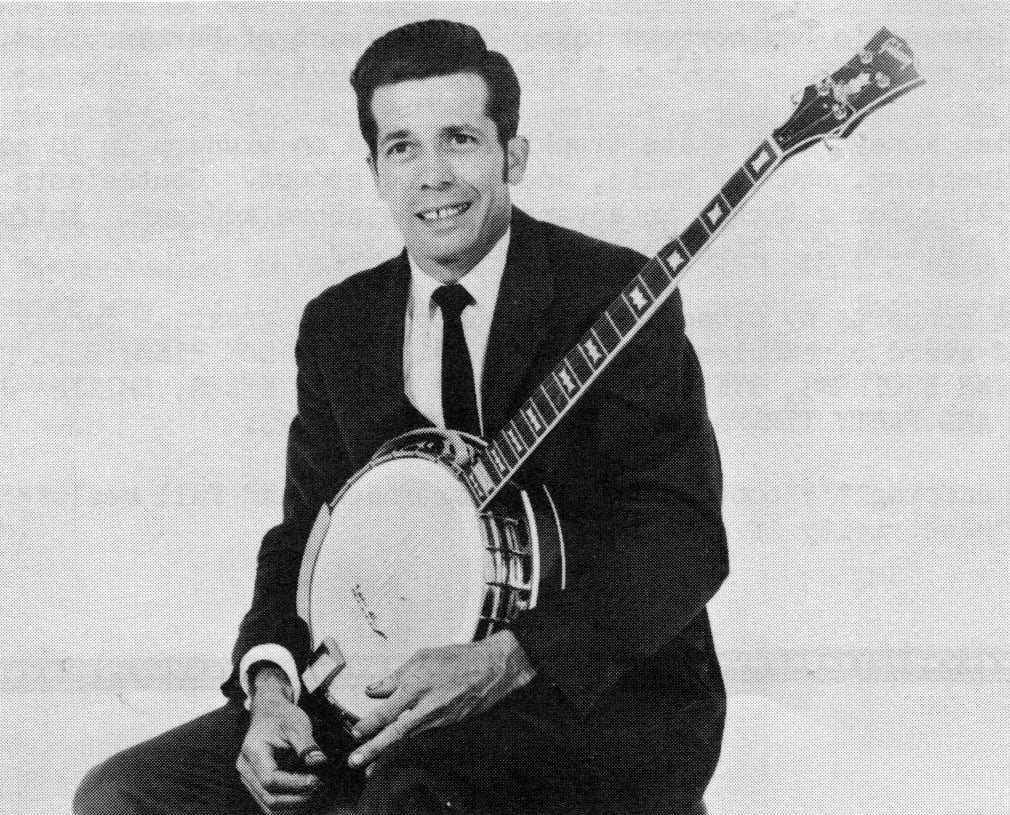

Truly one of the pioneers of country music is Johnny Whisnant, who plays five-string banjo. His career as a professional musician spans a period of more than 35 years. Unfortunately, he is perhaps the most misunderstood and certainly the most underrated musician in bluegrass music today. Recently, he and his wife, June, granted me a series of interviews at their Herndon, Virginia home, where we talked at length about his background and his music.

From Lenoir, North Carolina, he was born December 12, 1921. “Lenoir, that’s . . well, you’d have to be goin’ there, because you could by-pass it goin’ anywhere you wanted to.” His father, John Wisenhunt (Note: Johnny’s father spells his

name differently), was an old-time banjo picker.” He played the old way, you know, as far as his limit would go. He never got below the fifth key hardly . ..and he played with his fingers, he didn’t play with a frail.”

Johnny became interested in banjo playing early in life. “Actually, when I got interested in the banjo, I was 5 years old. Now I’m not gonna say, like a lot of them said, that I was born playin’. I wasn’t, and I wasn’t born too smart . . I mean as far as talent is concerned.” His first attempts to play banjo were during an illness. “I had kinda of a little ailment there, and the only way they could keep me in the bed was let me fool around with that banjo. I got my daddy to tune it. It was a fretless wonder . . didn’t have any frets, and as long as it was in tune, I’d try to play it. Try to pick out tunes, but I couldn’t play it . . 5 years old, I couldn’t play. Before I could ever play and go out and be in amateur contests, I was . . oh, I’d say 7 years old was about the first one I ever entered.”

He spoke of banjo players remembered from his youth. “There was guys like Hess Starr, Tell Reed, Jess Fulbright . . old man Clay Everhart. I guess the only one of the old banjo players that’s any older than I am that’s still playin’ would be Snuffy Jenkins. He was in Columbia, South Carolina back in them days. Snuffy did the same thing I did. He learned from this one and that one, and he could play as many types of banjo as any man I ever knew, Snuffy Jenkins could.” These old timers all used three finger techniques. “They played a three finger type of banjo playin’ . . mostly back-up though. One that stands out would be Charlie Poole. Now he’s the man that enthused me to play banjo. That sound is what sold me on a banjo.”

“There was only a few banjo players back then that really stood out as far as instrumentals, and that would have been Clay Everhart and Tell Reed. There was one guy that comes to mind, earlier than Snuffy Jenkins. A fella by the name of Oliver Webb . . now he played some instrumentals too, and also with three fingers. It was a peculiar type of banjo playin’, but good. They played tunes like ‘I Remember You Love In My Prayers’ . . I still play that tune myself occasionally. It was extremely good banjo playin’, but it would be kinda peculiar in this day and age.”

“I’ve heard “Devil’s Dream played when I was a boy . . a frail hand . . and I worked two months a-tryin’ to get that . . I wanted to adapt a three-finger roll to this kind of thing, and drew a conclusion it was impossible, it couldn’t be done . . but I’ve heard ‘Devil’s Dream’ played, and there’s a guy in Arlington, Virginia . . I don’t know his name, but he can play ‘Devil’s Dream’ as pretty as any man I ever heard in my life, and you’d swear he had on picks . . and he’s doin’ it with a frail lick. I even tried to frail it, but that’s out. I couldn’t learn that.”

“I never could learn Dave Macon’s or Grandpa Jones’ style because it didn’t suit me. The banjo didn’t have the right kind of sound . . and I have trouble to this day a-gettin’ a banjo to sound the way that sends me. I mean, maybe you like a real sharp pitched sound . . a real keen driving sound. Well, most people does. They think that they’ve got somethin’ outstanding if they got somethin’ that’ll cut like a knife . . but you can get a banjo so sharp, so shrill, that you’ve destroyed the music . . you’ve destroyed the tone . . you’ve destroyed the sound of the banjo. For instance, if you could get ahold of the record that enthused me to play a banjo, you’d wonder how that thing could enthuse me to play. It was ‘Monkey On A String’ by Charlie Poole. It wasn’t the way he played it. It wasn’t the fact that he played it with three fingers. I couldn’t have cared if he played it with his toes. The sound . . it drove through you. I mean it was somethin’ that stuck in your ears. I played that record so much . . and my sisters would say that they couldn’t hear the banjo. I said, ‘Well, you’re deaf if you can’t hear the banjo!’ . . so I’d put it in my wagon and pull it off in the woods and play that Charlie Poole record, and get my ear right in that speaker on that little old crank phonograph. It wasn’t the type of playin’ he was doin’, which was a three-finger roll, and all. This wasn’t what drove me out of my mind. It was the sound that came off that banjo. It was that one particular tone that come out of there that stuck with me all through the years.”

When Johnny was about 10 years old, he met Carl Story. “Carl was workin’ in the same furniture factory as my dad. Once I went down there and stayed the day with my Dad. Carl was there and had his fiddle, and there was a guy by the name of Wade Saunders who played guitar . . he worked at the same place, and we got out there in the parking lot of the factory on lunch hour and just slammed off some out there in the field.” Johnny didn’t think any more about the incident. “I wasn’t even thinkin’ about playin’ music . . didn’t have any idea of goin out professionally. I was in the game chicken business, raisin’ games . ’. I’ve done that all my life. One day I looked down the road and there come an old black Chevrolet that I hadn’t never seen before . . and it was Carl, wantin’ me to play the next weekend.”

Soon they were playing for square dances at schools and in private homes. “It was a demand for bands to go to peoples houses and it was a big thing to have square dances . . and that was the first playing we did.” Johnny was 11 years old when he launched his career.

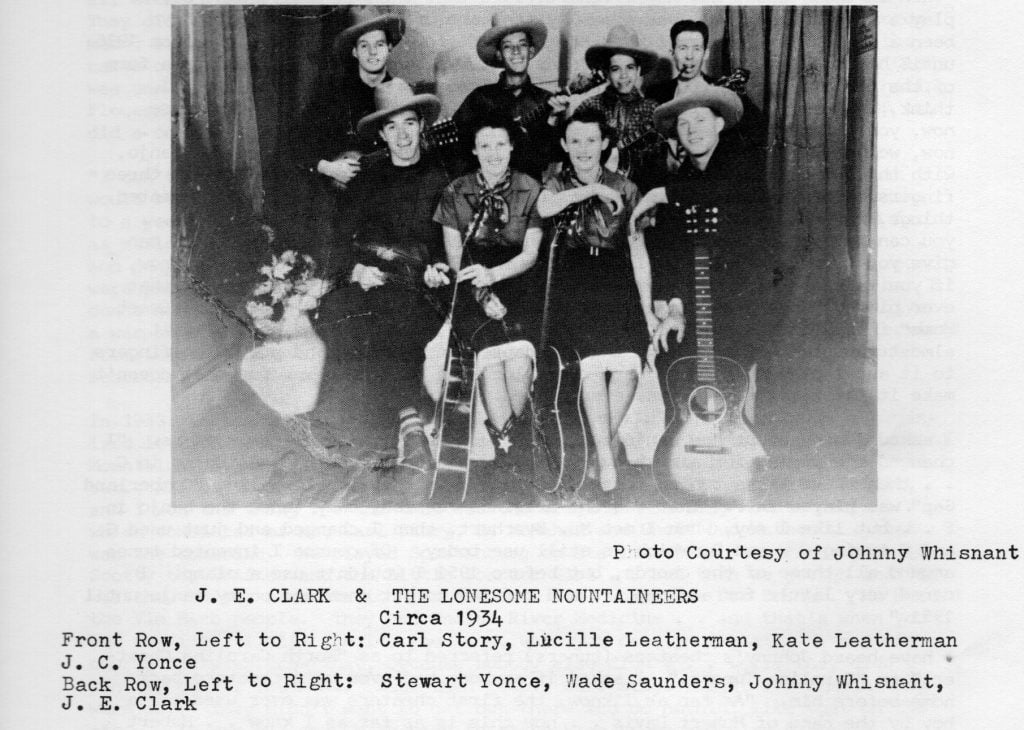

They first appeared on radio at Spartanburg, South Carolina. “The first radio show we ever had was at Spartanburg, in 1935, and we went to working for Doc Durham . . for the Vim Herb people. Now this was under a heading of J. E. Clark and the Lonesome Mountaineers . . but Carl played fiddle in the group . . he worked in the outfit just like I did.” Other members of the band were Lucille and Kate Leatherman, J. C. and Stewart Yonce, and Wade Saunders. The Leather- man Sisters had previously appeared with Gene Autry.

In 1936, Johnny met the man who was to have the greatest influence on his style. “I won second place in a banjo contest, against Tell Reed and old man Clay Everhart . . Hess Starr . . and Hubert Lowe, he was a banjo player back in that day too . . and he was good. They all played like Snuffy Jenkins, you know, or similar to that. Even though this Lowe fella was a better banjo player than Mr. Everhart, he didn’t have that sound, he didn’t have what I wanted. When I seen Mr. Everhart play with them three fingers, I had to know that. He had what I wanted, and as far as that goes, he still does have what I wanted . . I never did get part of it. He always was a better banjo player than I was, and . right up till the day he died, he was a better banjo player than I’ll ever be probably. He was the man I had to have to teach me . . and I betch it cost my daddy a thousand dollars, a-goin’ backwards and forwards to him after we found him . . and money was scarce back then . . but Dad, he wanted me to play so bad, and he didn’t regret it.”

Johnny started using a three-finger roll under the tutorship of Everhart.

“To watch him do it wasn’t enough. He almost had to work my fingers to get me to do it. As I said before, I wasn’t a musically talented guy. What talent I had, I made. I wasn’t born with any talent . . I don’t think anybody is.

“The first thing that I did when I started playing with a three-finger roll,

I learned a G chord . . a four-fingered G chord, and a C and a D chord to go

with it, and I backed up . . that’s the way I backed up, with a roll that no

body does to this day . . nobody does it but me. Now that’s a roll that was invented long before me or Earl Scruggs either one was ever born. An old fella by the name of Dock Walsh . . I think Dock Walsh is still livin’, taikin about the old banjo players . . cut ‘Bring Me A Leaf From The Sea’ (with the Carolina Tar Heels) . . he was a good friend of Doc Watson’s . . and he played with that three-finger roll.”

I was curious about how far back Johnny thought the three finger roll went.

“The man that taught me, Mr. Everhart, said that the man that taught him to play a three finger roll was a man by the name of Cooper, so it must have been a long time, because I knew Mr. Everhart for at least . . well, from 1936 until he died.” I tried to draw Johnny out by suggesting that perhaps a form of the three-finger roll might date back to the turn of the century. “I think, basically, that it goes back as far as banjo playing goes, because . . now, you can say that somebody invented this or somebody invented that . . now, we gotta put credit where it’s due. I’ve invented things on the banjo, with three fingers. Earl Scruggs has invented things on the banjo with three fingers. I think most banjo players has . . Don Reno . . we’ve all invented things, but now here’s where everybody seems to have been misled. See . . you can have an idol and you can give him all the credit, or the public can give you credit, but the public don’t know all the time . . like right now, if you talked to a man, he’d swear that Earl Scruggs was the first man that ever played ‘Home Sweet Home’ in C . . Hell, my daddy could play ‘Home Sweet Home’ in C . . that’s tuned in C with the bass run down, and he played it almost the same notes . . and then I adapted it from him and put three fingers to it and I played it, then Earl come along and played it . . but that doesn’t make it the first time it was ever played.”

I asked Johnny about the banjo tunings he used back in those early years. “I changed the tuning for almost every tune we played. There was a tuning in C . . then there was a tuning that we did in F, which . . originally, ‘Cumberland Gap’ was played in F. That was the original version, they tuned the banjo in F . . but like I say, when I met Mr. Everhart, then I changed and just used G and C tuning . . and D, which we still use today. Of course I invented tunes around all three of the chords, but before 1951 I wouldn’t use a clamp. I cared very little for a clamp . . .and refused to put cheaters on my banjo until 1951.”

I have heard Johnny’s cheaters (tuners) referred to as “North Carolina Cheaters” or “Carolina Tuners.” I asked if anybody had ever used cheaters back home before him. “As far as I know, the first cheaters was ever used . . a boy by the name of Hubert Davis . . now this is as far as I know . . Hubert Davis used the first cheater. Earl Scruggs made ‘Earl’s Breakdown’ and he didn’t use cheaters, he turned the key . . but Hubert Davis, when he did the same tune, he made him one cheater and put on the second string . . that he could lower and raise the second string. Now as far as I know, that was the first cheater ever made. Then when ‘Flint Hill Special’ came out, Earl made a set of cheaters, one for the second and one for the third. I didn’t like either . . I didn’t like none of the types of cheaters they had then, because you had to take two fingers to use them. I made several sets like them, that was an improvement of any I’ve seen, but you had to take two fingers. So I made mine . . and they wasn’t ‘North Carolina Cheaters’ . . they was made in Florida. I was livin’ and workin’ in Florida, so actually the invention was made in Florida, and to be fair with everybody, I left them on my banjo for 12 years before I even registered them or anything . . and see if anybody could make a set like them.”

His cheaters are very unique in that he can operate both of them at the same time. “Like tunes in ‘Whoa, Mule, Whoa,’ you can’t possibly play them like I do unless you got cheaters like mine.” I was curious if anyone else had cheaters like his. “Except my students, there’s about . . I’d say, a good 25 people that has ’em. . but if they do have ’em, they got them either from my students or that I sold them outright to them . . because nobody has come up with that thing yet.”

Johnny can’t recall the year, but sometime in the mid 1930’s, Carl and he cut several records. “We cut some records in Atlanta, Georgia, when we had to drive all over kingdom come to get a place where you could cut records back then. They didn’t have tape recorders, they used old discs. They was some records made, but whether they was released or not, I don’t know. I can recall the names of the songs . . ‘You’re Bound To Look Like A Monkey When You Grow Old’ was one of them . . ‘Careless Love’ . . ‘I Like Mountain Music’ . . ‘Gathering Flowers From The Hillside’ . . that’s one that Dud Watson and I teamed up on, did a duet . . such as it was. It was pretty bad.”

“I don’t know if any of them was released. The only man could answer that would be Carl himself. Things like that took so long . , it’d be six months to a year before you ever even heard from it. Times were movin’ fast as far as music was concerned, ’cause you could pick up a dollar easy, you know . . and people moved a lot. You could forget things . . I mean even if the records were put in process and even was released. They were cut for Columbia, but I don’t know if the records were ever released or not. If they were, I’d give a war pension for a copy of them myself.” (Note: As near as can be determined from information available at the time of this writing, the above-mentioned recordings were never released. WVS)

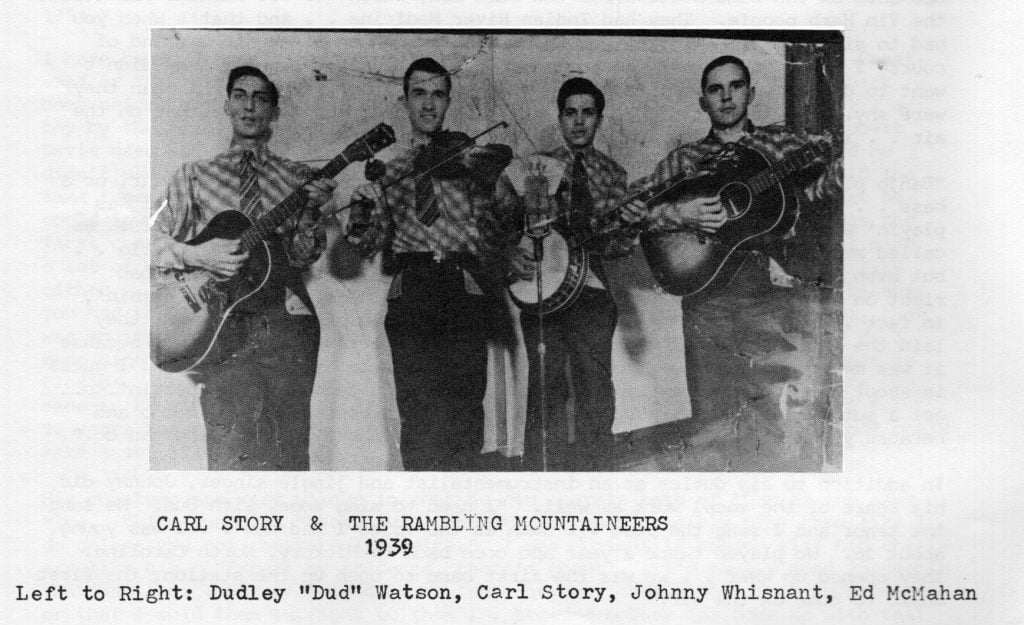

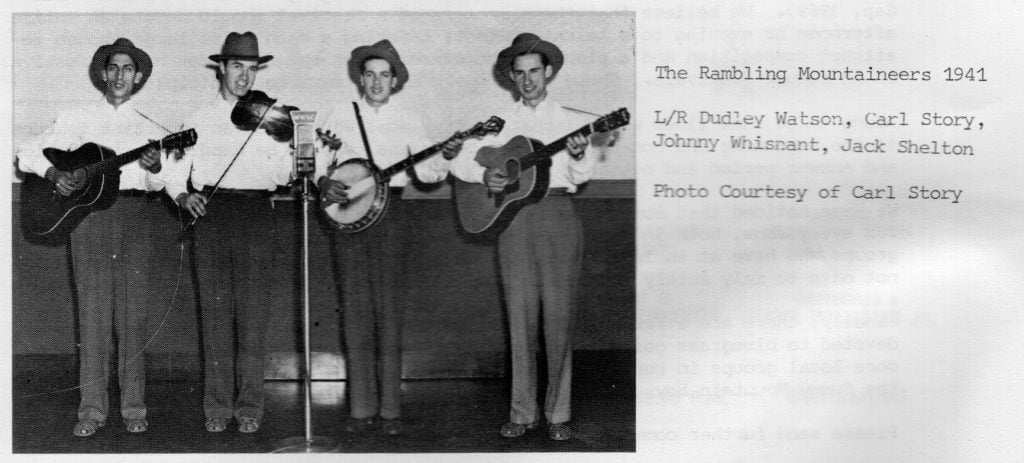

In 1937, Carl and Johnny took over leadership of J. E. Clark’s band, reorganized it with new personnel and changed the name to Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers. “We drew straws, and the name was mine . . that I had figured out. All of us had names and we drew straws to see what name we’d call it, and I won the thing . . and that was the original Rambling Mountaineers . . which consisted of me, Carl Story, Ed McMahan and Uncle Dud Watson . . that was the comedian. We played Spartanburg on station WSPA. Our first job with Scotty the Drifter and the Little Boarder Girl . . but then we got an individual show on the same station for the same man, which was Doc Durham. He headed the Vim Herb people. They had Indian River Medicine . . and that’s when you had to sing a little jingle, you know, when you came on the air . . and of course I always drew that, because nobody else didn’t . . well, they didn’t want to do it, you know. Back then people were stage fright . . I mean they were shy. They didn’t want to get out there and do nothin’ like that on the air . . it was bad enough to have to stand back there and play.”

“Banjo players are different. Most any type of fella can play a guitar, or a bass . . but it takes a certain type of a man to play a banjo. When I was playin’ with Carl, they laid the load of the band right on my shoulders. He called me ‘Half Pint’ back then, I was so small and the banjo was so big . . but even at an early age, 12 . . 13 . . 14 years old, they laid the load right on me. I didn’t want to lead the band, I didn’t want to say nothin’, in fact . . back then it was hard to even get me to say hello . . but they laid the whole load on the banjo. It was up to me to outline it, not because it was me, but because of the banjo. Now you got to be ornery enough, I guess is about the word, to get up there and do what you can without expectin’ to get a pot full of money. You gotta get out there because it’s a banjo and because you want to get a sound out of it that you know nobody else can do.”

In addition to his duties as an instrumentalist and jingle singer, Johnny did his share of the vocal work as well. “I used to sing some, with Dud. He sang the tenor and I sang the lead . . such as the voice I had now . . I was young, about 16. We played there a year and come back to Hickory, North Carolina. They opened up WHKY . . we was the first band to open up the station, the first music to come on the air.”

They were soon being booked by one of the big agents. “There was a guy by the name of Hall Houp . . he was bookin’ Nashville acts . . Eddy Arnold, Roy Acuff. He was one of the first bookin’ agents I ever knew in my life . . he started bookin’ us . . and in 1939 we thought we was flyin’. We were . . we were makin’ money. We played a tour through Maryland, and he booked us in with several of the bigger acts. Eddy Arnold, Bill Monroe . . Clyde Moody had broke loose . . he had a band, and we played right in with these big shots, you know.”

“When we left Hickory . . Houp, he still booked us . . we went to WWNC, Ash- ville, North Carolina, in the early part of 1939. We was on the Farm Hour at Ashville, and we stayed on there until I left the band in 1941 . . I went in the service in February of 1942. Now this is the reason why that you hear very little of me now, because when I went in the army, I didn’t sweat anything. I mean I was top dog, but when I went in the army I fell out of circulation. Of course, there was 15 banjo players tried to take my place. I could call their names, but I won’t. Carl wouldn’t have none of them. They didn’t do the stuff we did . . we had a thing that we did back then . . ‘Bugle Call Rag’ . . Carl took the first part and I’d take the second. We had ‘Steel Guitar Wobble’. . ‘Farewell Blues’ and ‘Careless Love.’”

I was surprised to learn about “Farewell Blues.” “I was playing ‘Farewell Blues’ back in 1939. It was an old orchestra tune and I used to have an old record of it. I don’t know who the orchestra was, but I liked the melody.

We did lots of tunes like that . . Carl and myself . . ‘Bugle Call Rag’ was the same way. We did that back in 1939.”

While they were playing the Farm Hour, a lad named Don Reno frequented the studio. “He would come around and watch me play. Seemed like everywhere I would go, sooner or later Don would be there. I don’t know if it was because that he liked my style any better than he did anybody else, or whether he was just tryin’ to learn some banjo. Don says to this day that I was the man that enthused him to play. I think that I enthused quite a few young musicians back then . . and I think they learned somethin’ from me. Not that I taught any of them . . . but at least they learned one thing, that the banjo is a substantial instrament. “

“When he started playing, Don had no place to go . . hardly. Before Don had ever started playin’ at all, I was already king bee. I was somethin’ to shoot at . . and a hard man to shoot at. I give a lot of people a lot of trouble back then, young and old. When Don started playin’ a banjo, he didn’t want to play like Jess Fulbright, or Clay Everhart . . he didn’t want to play like Johnny Whisnant or Earl Scruggs . . and I admire him for that. This is one thing that stands out in my mind about Don, because he didn’t imitate.”

I recently received a letter from Carl Story, in which he fondly recalls those years with Johnny. “I count him one of the finest banjo players there is anywhere. He could play tunes I have never heard anyone else play . . Earl Scruggs came up to see us one day (at WWNC), and Earl said that Johnny had some of the best licks he had ever heard. Earl at that time was working in a mill of some kind at Shelby, North Carolina.

Part II

July 1970, Volume 5, Number 1

In the latter part of 1941, Ed McMahan left the Rambling Mountaineers to enter the service. “Ed was a good guitar player. The guy that taught him to play was Wiley Morris…and they play as much alike as any two men I ever heard in my life. Back when Roy Acuff had out some songs and Ed was doin’ quite a few of ’em, and Uncle Dud (Watson) would sing tenor with him and try to imitate old Oswald…tunes like ‘Precious Jewel’ and ‘Wabash Cannonball.’”

McMahan’s place was taken by Jack Shelton, of the Shelton Brothers. “Curley and Jack Shelton is the way they billed themselves. Curley played the mandolin and Jack played guitar. After Jack came with Carl, he and Dud sang some together and he sang a part in the quartets. After I had gone in the army, Curley and Jack both played with Carl.”

Johnny remained with Carl Story until after the outbreak of World War II. “The morning that the news came out on the radio, the guys were goin’ up to enlist. . . and we would look out the window and see ’em…we was up at the radio station (WWNC), and there was droves of ’em.” Knowing that he would soon be called into the service, Johnny quit the band late in January of 1942. Three weeks later, on February 16, 1942, he was drafted.

Johnny was assigned as an infantryman to Company I, 313 Infantry Regiment, 79th Division, and participated in 4 major engagements in Europe. While in France, he received a wound which would impede his post-war musical career. He was struck in the right shoulder by a partially spent German Mauser bullet. The wound was not serious, but the Army surgeons, in a vain attempt to remove the bullet, damaged nerves leading to his right hand.

On September 25, 1945, Johnny returned to civilian life, and tried to pick up the pieces of his career. “I still had the old banjo…the pre-war Mastertone. I strung it up with new strings, put a new head on it and tried to play…and I knew it’d be a long road ahead of me if I ever played again.”

Carl Story had reformed his band, and was playing in Knoxville. The Sheltons were with him, Wiley Birchfield was playing banjo, and Cotton Galyean was on bass. “I went back to Carl, in hopes I’d get a job back…knowin’ I couldn’t-cut it. I mean, there was no question about it, I couldn’t do it. Proud as I was, I wouldn’t tell nobody I’d had the accident, and I still don’t want to stress the fact that I did get a bullet wound, and it interfered with my playin’…I don’t want that. Anyway, then, I didn’t tell nobody…it was just I was out of practice as far as anybody knew. I went to visit Carl and he didn’t talk to me like he was ever gonna use me again..which maybe he was in the right to do that, you know…I wouldn’t say he wasn’t…but I wasn’t good enough and I knew it. Wiley was in practice, and he did do the stuff…he did know what they were doin’. I had been in the service, and I didn’t fit back in the musician crowd…they didn’t seem to accept me like they did when I went in. I was a has-been as far as they were concerned, and they let me know that they felt that way…all of ’em.”

Disillusioned, Johnny went home, more uncertain than ever of his future. “I was so disappointed because everything had passed me up while I was in the army. I’ve always had a lot of pride…when it comes to playin’, and I didn’t want to get out there and say, well I’m holding the banjo…I wanted to be able to pull my load.”

“The old banjo had a lot of memories…everytime I’d look at it I’d think…well, me and Carl done this…there was a little crack in the headstock, a thing that happened in a show date, you know, where I stumped my toe and threw the banjo… little different things like that. I thought, well if I did go back to playin’ I’d want a different instrument altogether, so I went ahead and sold it…almost gave it away. I sold a pre-war Mastertone for $50 to Hoke Jenkins. I tried to find it after I come to this part of the country. I heard that Rudy Lyle bought the banjo, then I heard Hoke kept it, then I heard a fella here in the Washington area had it, but I lost trace of it. I was gonna try to buy it back.”

His inability to play the banjo like he wanted to was a continual source of discouragement to him. He drifted around the country, and even went to the west coast. “I wandered around like a lost puppy…for I’d say…’45, ’46…for two years there, I just wandered…but I was smothered, I couldn’t stand it.”

In 1947, Johnny found a relatively unknown band playing in Morristown, Tennessee, that hired him. “There was a little group up there that had everything but a banjo. So I went and bought a brand-new RB-150…that’s all I could buy then. It wasn’t any good, but to me then, it was a banjo…it had 5 strings on it. My hand was still bulky, my fingers still spongy, and I couldn’t maneuver them like I wanted to. But I still had my left hand and I still had the knowledge. I knew all I had to do was just keep on exercising that hand till I got it back to where I could play.”

“It was a group that sang similar to Charlie and Dan…the Baileys. They sang some of their songs. This is where I heard of the Bailey Brothers for the first time. Charlie and Darrell Lane were the ramrodders of the group, and they were playin’ WCRK in Morristown. They also patterned themselves after the Cope Brothers …that was another group they liked a lot. Charlie and Darrell are still livin’ in or around Morristown. They never did do nothin’. They didn’t want to do nothin’, but they loved to play music, and it give me a chance to practice with guys that didn’t care. They let me struggle along with them until I got back to where I could halfway play.”

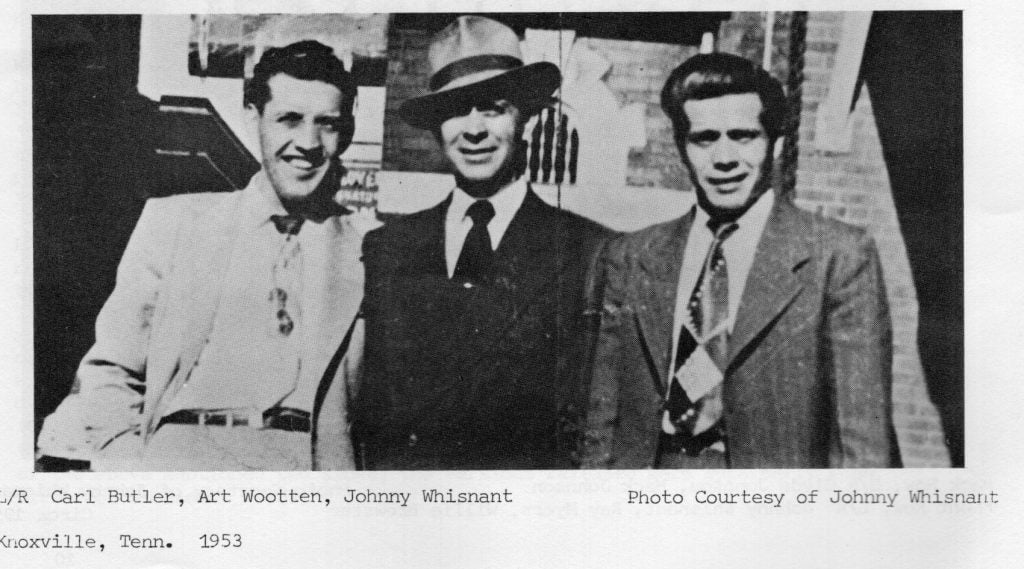

Johnny returned to Knoxville, and went to work for Carl Butler. In 1951, they cut a session for Capitol Records. “At first, Smokey White played the mandolin, and I played the guitar, Jake Tullock played the bass, Art Wootten played the fiddle, and Speedy Krise played the dobro, and Carl wasn’t gonna play anything. Well, Smokey couldn’t get off the ground with the mandolin. Dee Kilpatrick was the A & R man…he said we can’t have that, so we let Smokey play the guitar, and I asked him could I use the banjo…and he said, “Go get it, it can’t sound worse than what we got.” So I went and got the banjo, and we did the session with the banjo. Carl didn’t do a thing…he just sang, and that’s the way the session was cut…it stayed that way all night. We did eight sides…I can’t remember them all, but ‘No Trespassing,’ ‘Linda Lou,’ ‘String Of Empties,’ ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll’ was a few.” Johnny cut a record with Jimmie Skinner during this period, also for Capitol. “Me and Carl and Jimmie Skinner and Curley Lunsford was playin’ double-header show dates…with Art Wootten fiddlin’ for us. It was all right there together…about the same time.” Johnny stayed with Butler for only about four months. He still was not satisfied with his banjo playing, so he decided to give up music.

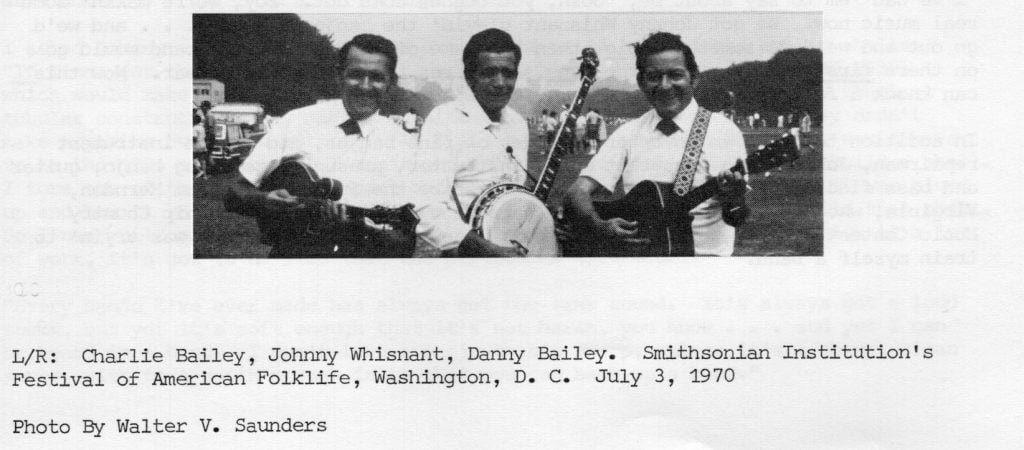

Back in Lenoir, North Carolina, he went to work for the Wayne Johnson Motor Company as a mechanic. He hadn’t been working there very long until Charlie Bailey came to town looking for him. “He asked me how long it would take me to get ready to go to Raleigh, to come on a 4 o’clock show the next mornin’, and I told him about 30 minutes. We packed everything we had goin’ and left that afternoon and went to Raleigh, At that time the band personnel was Charlie Bailey on mandolin, Danny Bailey on guitar, Johnny on banjo, Chubby Collier on fiddle, and Jake Tullock on bass. There was a female vocalist who appeared with them named Evelyn.

Johnny spoke highly of the Bailey’s fine musicianship and tight harmonies. “They had a great duet. A duet that I don’t think anybody will ever duplicate.” In late 1951 or early 1952, the Baileys moved to Roanoke, Virginia. “We were in Raleigh, so we swapped places with Flatt and Scruggs…they left Roanoke and come to Raleigh, and we left Raleigh and come to Roanoke. Chubby Collier left and Ed Amos took his place. He used a capo on the fiddle. There was another fiddler after him…Jackie Haskins was his name.” We fell flat on our face in Roanoke…and I tried to get Charlie to cut my salary but he wouldn’t do it. Charlie wasn’t makin’ no money…he was goin’ in the hole.

I just demanded that we take a $10 cut on my salary so we could all stay there, ’cause I liked Charlie and Dan. Buddy, I’ll tell you now, they were good to me… they treated me like a king and I respected them the same way…but we just wasn’t makin’ no money and I knew it couldn’t hold out like that and so I quit…more or less out of respect for Charlie and Dan.”

During the period that Johnny was associated with the Baileys, they made several recordings. “We cut some stuff that was supposed to have gone on Canary, but they was recuts made of ’em, and I don’t know if any of ’em hit the market or not. The only man that could tell you about that would be Charlie…whether I was on any of them or not. Hoke Jenkins had played some with him, and he had several different guys played banjo with him, so it could be any of them. It don’t necessarily have to be me. We cut ‘Bleeding Heart,’ and I believe we made a recut of ‘St. Louis Blues’…did a little bit different, but the same singing, you know.” (Note: Information received from Charlie Bailey via Gary Henderson indicates that none of the recordings that included Johnny were ever released. In the case of the above mentioned two sides, the versions released were apparently from different sessions. WVS)

Johnny’s break came when James Carson, Martha Carson’s husband, came to Morristown with a group of musicians and held a talent contest. “Willie Brewster, Lloyd Bell and Buck Ryan played the show they had that night…the special music, and I won the contest. Then I had to go to Knoxville…WNOX…on the playoff. I tied with a guy, and in the process of it, Willie Brewster and Lloyd Bell and Jake Tullock wanted me to go to work with them on WIVK on the Cas Walker Show. So I went over there and played with them awhile.”

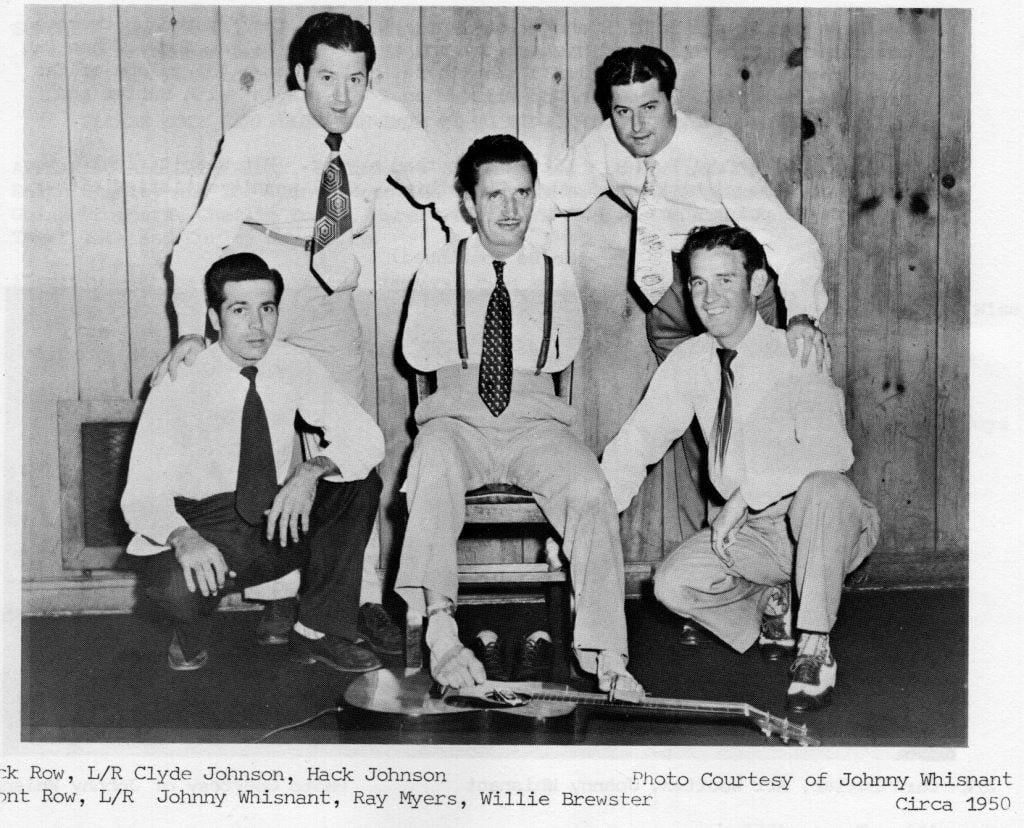

In 1950, the band split up. Will Brewster and Johnny decided to stick together.

“Me and Will joined Hack and Clyde Johnson. They had that armless musician, Ray Myers workin’ with ’em. I started out with ’em on WNOX, the Midday Merry-Go- Round.” From there, we moved to Mt. Airy, North Carolina. Things didn’t go too well for them there. “We done some of the Delmore Brothers’ songs, and we did some quartet stuff…gospel songs. We were tryin’ to compete with Mac Wiseman. He was on the same station, and he had Joe Medford playin’ banjo with him, and they were playin’ typical bluegrass, you know, and we just didn’t have it. The type of stuff we did just wouldn’t sell. I never did figure out just exactly what happened over there at Mt. Airy. Will Brewster, you can’t beat him. He’s one of the finest musicians I ever played with. Put him on a guitar and he’s great, put him on a mandolin and he’s great, he can play a decent fiddle…but we was just tryin’ to sell something that the people wasn’t buyin’, that’s all there was to it.”

In March of this year, BU’s Gary Henderson interviewed Charlie Bailey at his home in Wilmington, Delaware. Charlie had this to say about Johnny; “I would have to say that Johnny Whisnant is a banjo player that don’t have to take a back seat to anybody. Between him and Snuffy Jenkins…that would have to be two of our greatest and they have never got the publicity or name that they should have.”

Once more, Johnny returned to Knoxville, this time to team up briefly with the Brewsters. “I had come back to Knoxville with the intention of quittin’…Bud had growed up then and he was playin’ guitar. So then for a short while there, me and Bud and Will, Ray Myers and Al Bevins on bass…we went and played some shows. We went up to Scottsboro, Alabama. Every time I’d lay my banjo down, Bud, he would pick it up, and he would worry me to death with that blamed banjo. He finally got him a roll, and he’d just worry you to death with that one roll. We played in Scottsboro a little while, then we went to WVOK in Birmingham. Rebe and Rabe had been playin’ there before us. I believe Rabe was still around. We wasn’t makin’ any money so I pulled out and went back to Knoxville.”

Johnny went back with Carl Butler in late 1952. “Pearl was beginnin’ to sing once in a while then. She was workin’ in a restaurant and she’d get off for lunch, and do the show with him at lunch time. Art Wootten was still playin’ fiddle, and Clyde Varner was on bass.”

“The Baileys hadn’t stayed in Roanoke long after I left. They busted up there, and come back to Knoxville, and started to work on the Cas Walker Show…then Dan stayed on the show. Charlie wouldn’t stay there, and he got a job in one of Cas Walker’s supermarkets. He was in Knoxville when I was playin’ with Butler and them, and ever so often, Charlie’d some up to the station.”

Johnny stayed with Carl Butler a little less than a year. “It wasn’t right. We wasn’t playin’ the right kind of music or nothin’…Carl wasn’t satisfied either.

So I got to the point where I just quit.”

Part III

August 1970, Volume 5, Number 2

Late 1953 found Johnny working as a one-man act at WKBC in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina. He was billed as “Cousin Johnny and His Banjo.” It was an early morning show. “We had these little old things that you slice meat and vegetables with, and garden tools … and one of those crank things that you sow grass with … little old things that you sell. You’re talkin’ to the farm people, so they figured if I’d get on there talkin’ the way that I talk, playin’ the banjo, and singin’ a few … what you might say, makin’ a mock of music, that’s just about what I was doin’. I think they call it P.I.’s, or somethin’ ’nuther.”

While he was appearing at WKBC, Johnny cut one song with the Church Brothers. Johnny Nelson, the banjoist with their group had been killed in an auto accident. Johnny relates the tragic circumstances that lead to the session. “Johnny Nelson was in the service then, and he had brought his car to me to do a valve job on it . . . he had a burnt valve on a ’49 Mercury. I did a valve job on it, and he come in on leave to get it . . . spent his leave up, and started back to camp and wrecked his car and killed him.”

The Church Brothers had cut some records for the Blue Ridge label with Johnny Nelson on banjo, but they had an extra side left over. They needed one more cut so they could release another record. Drusilla Adams, owner of Blue Ridge Records, then located in North Wilkesboro, came to see Johnny.

“She come to the radio station, talked to me and invited me over to her place to listen to some of the tapes. I went over there and while I was there, Joe Franklin come.” Johnny agreed to cut the side, but with the understanding that Johnny Nelson would be credited as the banjo player. “She said she wanted to back up that other side of Johnny’s record with . . . somethin’. Now I don’t know the name of the tune we used, but I do know that the one that was on one side was altogether different. It wasn’t the same group … they used the Church Brothers on the other side, and supposed to have used Johnny Nelson’s name on the other side … same as they used on the front side. Instead of that they put the wrong name on there as far as I’m concerned … and JE did the banjo playin’ on that extra side … of course, it wouldn’t show up as my style, because I wasn’t tryin’ to play my style, noways … I was tryin’ to play Johnny’s style … but they credited it to Gar Bowers. They give credit because Gar, by then, had took Johnny’s place.”

“I don’t believe … and this is my opinion, and my opinion only … I don’t believe Gar Bowers cut any records with the Church Brothers. I don’t believe that he cut the first tune. Now they say he did … put his name on some … but I don’t believe he did. I still believe that me and Johnny Nelson was the only banjo players on the records the Church Brothers cut … and I only cut one of ’em. I didn’t care nothin’ about it … I mean, all I did it for … I didn’t do it for any publicity for myself … I did it for Johnny Nelson. Just because I had a lot of respect for Johnny. I still don’t want no publicity out of it at all, except … I know one thing, that I don’t believe Gar Bowers’ name should have been on it.”

Johnny remembers only one of the Church Brothers actually participated in the session. “There was Joe Franklin on guitar and singin’ lead. Joe could sing exactly like that Church brother. I mean, he could imitate him to the letter. Not only that, he could imitate Mac Wiseman to the letter … he could imitate several guys. Ralph Pennington was on fiddle. One of the Church Brothers was on mandolin and sang tenor. Then on bass … seemed to me it was Dean Walsh, Dock Walsh’s boy. I believe Dean was with me when I went over there. Dean played some with them too. Played some dates with ’em.”

Once again, Johnny returned to Knoxville, and went to work as an auto mechanic. During this time, he played a number of show dates with some of his former colleagues. “Nothin’ big, just somethin’ to keep my fingers in music. We played some dates over in Gatlinburg (Tennessee). Charlie and Dan (Bailey) was around … they had busted up, and ever once in a while, they’d get back together and play a show date … and once in a while Charlie would get a group of his own, and I’d play a show date with them, but nothin’ steady. In fact, I was to the point where I didn’t know whether to keep on with music or just drop it, or what to do.”

One show that stands out in Johnny’s memory was in 1955. “We played a show in Robbinsville, North Carolina. The crew that played that was Sonny and Bob Osborne and their group, Carl Story was there … Claude Boone was with Carl … I believe Red Rector was with him, and if I’m not badly mistaken, Fred Smith was in on that show date. Then there was Charlie Bailey and Dan, Carl Butler and Jake Tullock … Art Wooten, I believe, played the fiddle. Even old Fiddlin’ Bill Hensley was on that show. Fiddlin’ Bill lived in Robbinsville. The Brewsters was there. I was supposed to play with Charlie and Dan Bailey, but I think I played with everybody but Sonny and Bob that night. I think I played with the Brewsters, I know I played a tune or two with Carl Story … I played some with Carl Butler and with Charlie and Dan. We had a good time. I’d do somethin’ like that and then I’d get enthused and I’d want to pick … man, I’d want to join somebody then, you know. I’d get restless, and quit a job for a little while and I’d move around and try to organize my own outfit … and still not do nothin’. It wasn’t till I went to Florida that I actually settled down and decided that I was gonna just make music … one way or the other, I was gonna make it.”

Johnny moved to Morristown, Tennessee, and worked for the Lincoln-Mercury dealership for a while, then opened his own shop.” I was just tryin’ to find relief in doin’ mechanic work … but the music was still there. I was still hungry to pick, and I picked at every chance I got. Everybody that needed somebody, I picked with ’em.”

In late 1957, Johnny moved to Florida. “I went down there as a mechanic … when I first moved to Florida, I was workin’ in Lakeland, then I moved from there to Winterhaven. I worked mechanic work down there until … I was in the shop workin’ away and a guy came in with a banjo … and he was showin’ off his banjo. I asked him to let me see it. I washed my hands and put on his picks … I didn’t have any of my own. I played a little tune on his banjo, there in the shop. From then on I had it in my mind that I was gonna buy a banjo and play.”

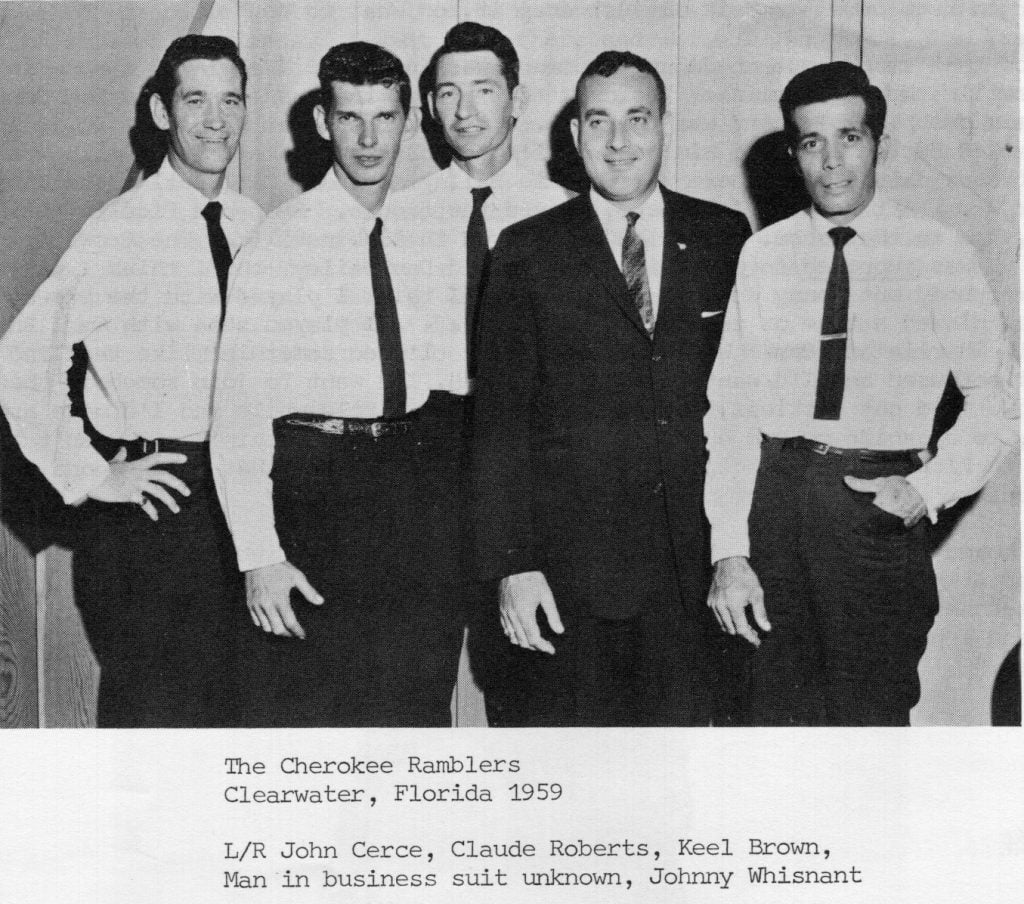

Johnny soon met a guitarist, Keel Brown, and together they formed the nucleus from which Johnny’s next band would develop. “We were visitin’ some people … this boy worked in the place where I did, and they said there was a boy from across the street that plays guitar. That’s how I got to know Keel Brown … and he had an old banjo. He let me take the banjo home and gear it up and fix it where it could be played … and we’d sit around and practice … and me hungrier to pick all the time. I couldn’t play on that one … so I decided to get one I could, so I bought me one … a new Mastertone. He and I’d still sit around and practice, so one day rolled around … we figured, well, we got enough material, we could put on a show. So we booked a few show dates. We organized a group and called it the Cherokee Ramblers! It got to be a pretty good little outfit.”

Working as a mechanic by day, and playing music at night soon began to have its effect on Johnny. “I’d try to work and play, and I’d stay out till late hours of the mornin’, then try to go in and work in the daytime … each day I hated it that much worse, until the day came when I just quit . . . and that’s the last mechanic work I’ve done . . . for money. When I walked out that time I sold my tools.”

The Cherokee Ramblers played dates in the Orlando-Tampa area. “Besides Keel, there was … Claude Roberts played the fiddle, and one of the finest fiddle players I ever knew … and John Cerce played the bass … he was a barber and he’d got just like me. He’d got to where that he just didn’t want to cut hair no more … he wanted to pick music.”

“Winter Haven was a good spot … plenty of radio, and it was close to Orlando . . . there was a recording studio in Orlando. Ralph and Carter (Stanley) was down there. They was playin’ in Orlando. We’d go over and visit them, and we

took the group and guested on their show. At that time we had Keel, Claude, and Vernon Derrick that plays with Jimmy Martin now. Vernon wasn’t part of our outfit, but he just happened to be along that night. That’s how he got the job with the Stanleys. They sent a man to find him and come to my trailer … we was livin’ in a trailer then, and they wanted to know where Vernon was. I give ’em

the address so they could get ahold of Vernon … and they hired him.”

“At that time the Stanleys had “Pap” Napier playin’ the guitar with ’em, instead of George Shuffler … and then, a short while after that, Pap quit and tried to get me to go play the banjo with him … he went with Charlie Moore … and I wouldn’t do it … I already had an outfit.”

Working for five years as an auto mechanic played an important role in strengthening Johnny’s right hand. Equally important was the fact that Johnny never gave up hope that he could regain his ability. “As far as the action of my hand, there wasn’t anything wrong … well, at first, if I moved one of these fingers (index and middle fingers, right hand), I had to move them both . . . but after I got that broke loose, there was nothin’ wrong with the action … but what it was, it was weak. These two fingers here were weak. That was where the problem was. I didn’t have enough strength, and without strength, you can’t coordinate them right … you can’t put ’em where you want to put ’em. Mechanic work did help … it strengthened ’em. Startin’ nuts with ’em . . . and of course you gonna start ’em with the closest hands … that limbered ’em up. It all helped . . . plus the fact that I intended that I was gonna play again, as good as I ever did.” Johnny feels that it was during his stay in Florida that he regained completely what the enemy bullet had taken from him. “My hand was fine, never was in any better shape, and when I left Florida I could play as good as ever, and I think better than I ever did.”

“I never did get disgusted with the boys. The only reason I left Florida, I just . . . there wasn’t enough people that was educated in bluegrass music . . . we’ll call it bluegrass music . . . it’s not. I mean, the kind of music I play ain’t bluegrass music. It didn’t come from Kentucky, but I mean . . .we’ll call it bluegrass ’cause that’s what we’ve decided to do . . . there should be another name for it, I still say.”

In 1959, Johnny returned to Knoxville. “But I didn’t stay in Knoxville very long.

I didn’t play nothin’ when I come back … I just went over and guested on the Brewster Brothers show … and I played one or two dates with Charlie Bailey when I first come back.”

In early 1960, Johnny moved to Ellicott City, Maryland, to work with Charlie Bailey. “Charlie sent me word to come up there … it was on the strength of Charlie that I come up in this part of the country. We played in a bar in Odenton, Maryland. It was just Charlie and myself and the Wells Sisters … and they sang the Brown’s songs, you know … Lou, she didn’t play nothin’, and Midge, she played guitar … so that put us with two guitars and the banjo … didn’t even have a bass or nothin’. And … we didn’t do nothin’ … I mean, the whole thing was out of kilter … we just didn’t do a whole lot. So, I left there and come to Laurel, Maryland.”

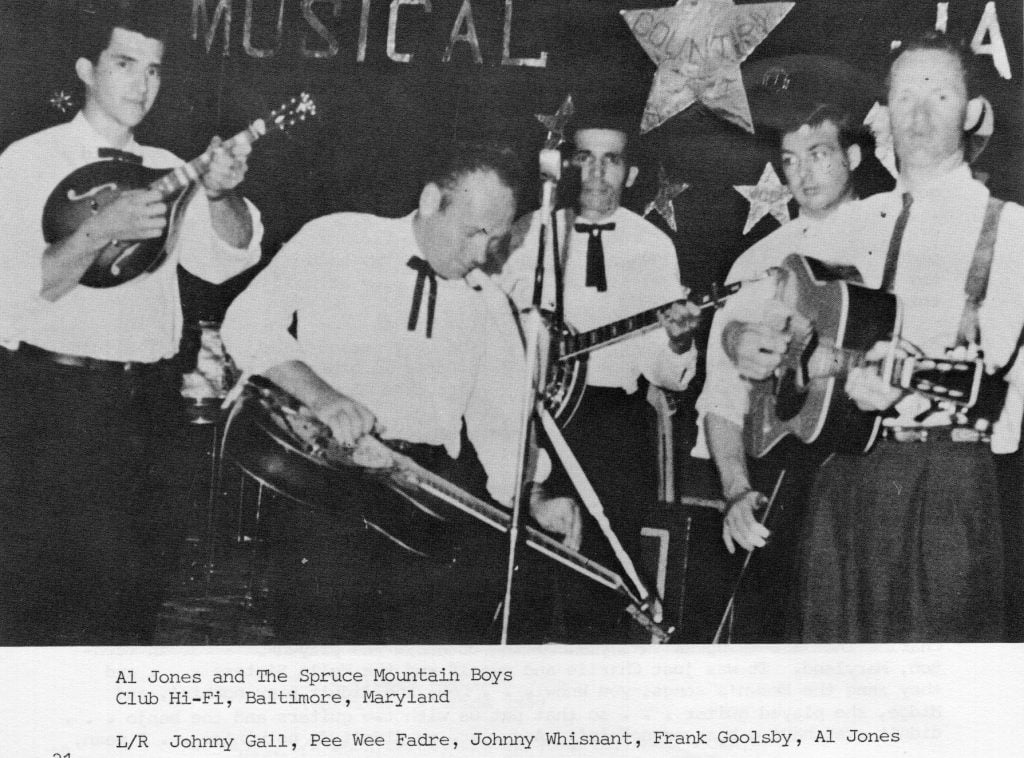

It was mid 1960 when Johnny moved to Laurel. “We got an apartment there, and I was lookin’ for Al Jones. I had met Al while we lived over in Ellicott City. He came over there to sing, and he had Earl Taylor with him … and I picked some with Al over there, and Al liked the sound of it. So I tried to find Al, and I drove around until I found him. We organized a little outfit … consisted of Pee Wee Fadre, Johnny Gall and Frank Goolsby, Al and myself … and we got quite a few dates … played some dates over in Hoverly Hall, in Baltimore, played one double-header over there with the Stanley Brothers. We played the Club Hi-Fi in Baltimore … a good place up there, and we played quite a few bars … and we had a good strong outfit.”

Like too many other good grass bands, this group was destined to be short lived. “Al took a notion he was goin’ with a different group, that were playin’ a little more than we were. When Al quit, I couldn’t get nobody to replace him. Al Jones is a good man, he sings either part in a duet, and sings it great. I couldn’t replace him, because he and I had songs worked up that we did, and I just couldn’t do ’em with somebody else, unless that they could do the same thing Al did … and that’s hard to find … so I had to fold, I had to quit. So, the boys just all went to playin’ with different groups, and I quit playin’.”

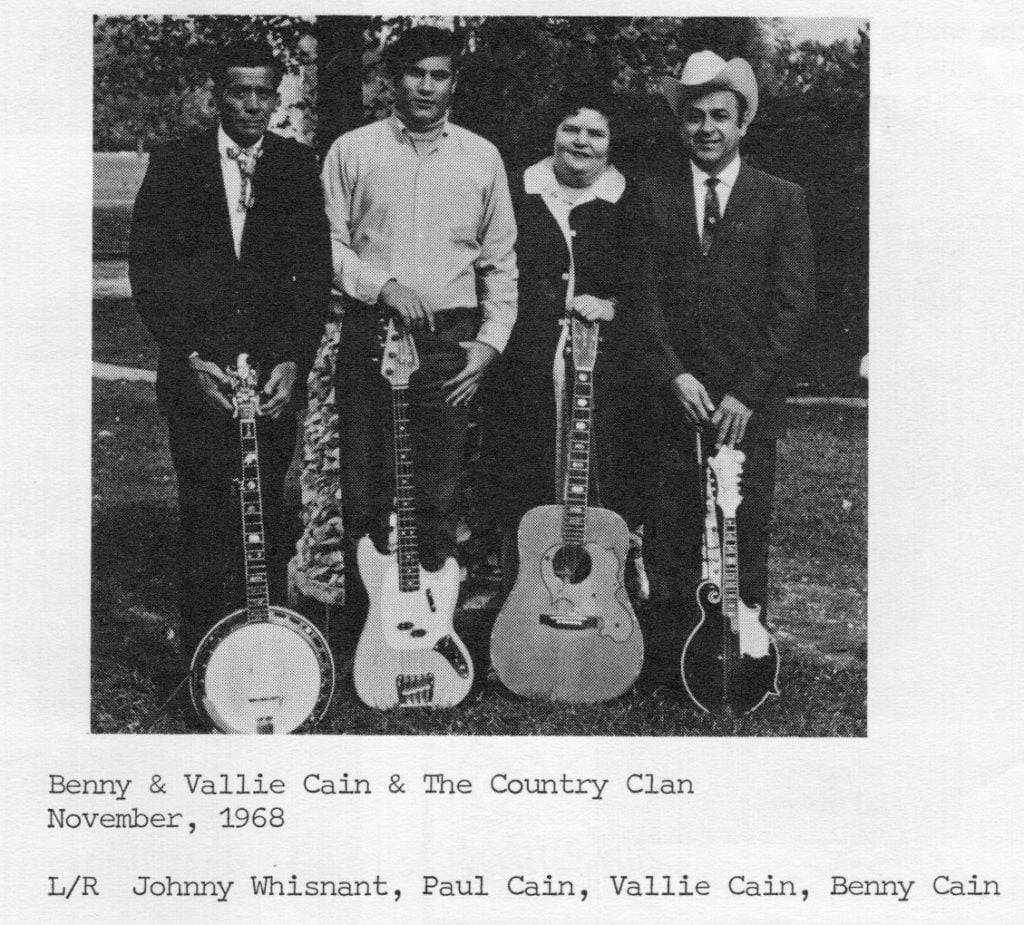

Early in 1963, Johnny began playing with Benny and Vallie Cain, with whom he has been associated, on and off, ever since. “One day, Bennie called, and asked me was I playin’, and I told him no that I wasn’t. He asked me did I want to play five nights a week … so I went to’ playin’ with ’em. We played the Cloverleaf in Alexandria, Virginia. The first thing I did with Benny and Vallie was play a radio program. I come over on a Saturday evening and cut a radio program to be played the next mornin’ … Sunday mornin’ on the Big K (WKCW, Warrenton, Virginia). We cut two shows that evenin’. I told my wife … I told June when I left, I said, “I may be back in a few minutes, ’cause I just happened to think, they’s a woman playin’ that guitar,” and I said, “it’ll probably be some helluva mess” … but when I got over there, and we rehearsed … we didn’t do much rehearsin’ … we tuned up and played a couple tunes, and started cuttin’ that radio show … and as it worked out, the guitar playin’ was O.K. It was fine, there wasn’t nothin’ wrong with it. I went on that night and played the Cloverleaf with ’em.”

Their longest engagement was at Jimbo’s, a restaurant in Yorkshire, just outside of Manassas, Virginia. “We played over at Jimbo’s … about four years. I made a little money with Bennie, and Vallie … they’re good people … and they was always just as good to me as they could be.” In addition to Benny, Vallie and Johnny, the Country Clan included Jimmy Delozier on fiddle and Don Mulkey on bass. Later, they dropped the fiddle, and Tom Gray replaced Mulkey on bass.

Johnny is playing on all of Benny and Vallie’s releases on the Rebel label. The most recent release was an album, which Dick Freeland, the owner of Rebel Records personally produced. “That was the first time that Dick had produced anything . . . was that one time. He produced it, and it didn’t cost a nickel. Dick was impressed with the music part.” The personnel on the session was Benny Cain, mandolin; Vallie Cain, guitar; Johnny Whisnant, banjo; Paul Cain, bass.

Conclusion

September 1970, Volume 5, Number 3

Johnny Whisnant’s great love for the 5-string banjo is apparent whenever the subject is brought up. Actually, around Johnny other subjects are rarely discussed. He is a veritable walking encyclopedia of banjo information, and can talk to you for hours about them without ever repeating himself. “Banjos has always been close to me . . . and this one particular sound that I look for. . . it’s a funny thing with me. I’ve had good banjos. I’ve owned more banjos, I guess, than any man my age . . . but I’ve had very few banjos in my life that suited me. The old prewar Mastertone that I had when I went in the Army, it was a good one. It was made in about 1934, or ’35 . . . somethin’ like that.”

“Now in this day and age, these people that talk about how they want a prewar … now, actually they don’t even know what they’re tryin’ to get. A prewar, as long as it was made on this side of 1930 . . . they be very little difference in the bottom part. Now the neck may have better craftsmanship than the newer banjos, but as far as the bottom part of that banjo, there was no difference in ’em then than they are right now. Maybe they was made out of brass, which in my opinion, it doesn’t matter too much. That’s only my opinion. I guess I’ll get arguments there. There’s only a few prewar banjos that’s outstanding, and I’d say that they made, in 1924, one model of a Mastertone that was identical like a Number 3 Ball Bearing, except it had a tone rim in it that was similar to a Vega. If anything, it was similar to some of the old Vegas.”

“When you speak of a prewar banjo, everybody thinks that anything that was made back of World War Two was prewar, see … that’s what they refer to. Now, when I speak of a prewar bein’ outstanding, it’s got to be made before 1930 . . . and that includes both the Florentine and the All American, because I never seen an All American that was tubular construction. I’ve seen several All Americans, but they’ve been solid bottoms like on this side of 1930. All banjos are, like the 250, like the Mastertone you buy now, like the Fender … like all the junk they’re makin’ now.”

“So when I build a banjo … when I build one of my own … I always take it on that one model A Number 4, and I build that banjo to the letter like that one particular 1924 model … which was the same shell as the Ball Bearing Number 3, the inlay in the neck was the same as a Number 3 . . . the headstock was the same as a Number 3 . . . that’s what I duplicate.”

I asked Johnny if he fabricates his own shells or if he uses old prewar shells.

“If I can get the shell like I want … which would have to be back of 1930, which would make it a tubular construction. As far as I know, 1929 was the last tubular construction they made. I think that on this side of 1929, they didn’t make anything but solid bottoms. If I did build one around a shell, it would have to be the 1924 or back. If I can’t get that type of shell, then I can build a shell. I tore one of the old shells apart and sawed it in two, and looked how it was glued up and how it was laminated and I come up with the answer of how to build that shell. So I can build one as substantial as the old ones … and if I do, which is a lot of work, it’s got to be like that one particular 1924 model.”

“Every banjo I’ve ever made has always got the same sound. It’s always got a loud sound, but yet it’s soft enough that it’s not harsh, you know … and yet I can be heard in a band. I don’t like a banjo that’s sharp, unless it’s a sharp, clean sound, with tone depth enough in it that you can back up a band.”

“To me, I think a banjo player stands out backin’ up a band. If you want to show how good you are, or how well you can play, you can show it a-backin’ a band up better than you can your instrumentals … because to me, two thirds of the banjo players that I hear right now, when they play an instrumental, they’re imitatin’. . . you can tell they’re imitatin’ somebody. Maybe some of ’em imitate Scruggs, or Sonny Osborne, maybe Don Reno or me, but you can tell it’s an imitation … but the one place you can’t imitate is when you’re backin’ up a band … and you really sincerely want to make that band sound clean and you want the banjo to play it’s part in the band, then there’s no imitation there. Then this is comin’ from the man that’s playin’ the banjo, you know. I never judge a man by his nice instrumentals … because in the first place, he’s playin’ somebody’s stuff … but when they’re backin’ up, they’re backin’ up the way they feel it.”

Johnny reflected on the nearly four decades since he launched his career. “All through the years it’s been real nice . . . playin’ music. I don’t have any regrets. I’ve played all my life … every picture I have, just about, is made with a banjo. Well, it’s just my whole life … but somehow, since I come out of the Army … even though I’ve had the enthusiasm to play, as much as I did when I was a youngster … and now I got the ability … but now there’s too many bands that only play part-time, and to me that’s sickenin’. I’d get me a job and think this is where I’m gonna stay, but they wouldn’t want to do anything.”

“I’m an easy guy to get along with in a band. I’ll go along, if anybody can show me that they got the ability to be a showman or that they can play music . . . I’ll let them go in front. I learnt that from good guys … from pros like Charlie Bailey and Carl Story … Carl Butler … old troupers, you know, that was in the business to make money. Anyway, I’ll let somebody go ahead and make the decisions … I don’t try to run my mouth. I’ll stand in the background and pick my banjo, as long as they do somethin’.”

“But they put me in a class as if I was just started in music, if I let ’em . . . if I just take a back seat … and I see ’em do things I wouldn’t do it I was runnin’ the band. Say I had an ace banjo player … or fiddle player … as far as I’m concerned, he’s an ace at it, and I’m a-gonna let him know that’s the way I feel about it . . . but the outfits anymore … the way they operate, if they get a man in there that’s willin’ to work and can do somethin’, and can help ’em along … help ’em gain popularity or somethin’, well then they don’t give him the publicity. They try to make a name for themselves off of the good man’s ability. It’s not just one group . . . it’s all the groups.”

“I’ve had ’em to say about me, “Gosh, you oughta come out. Boy, we’re makin’ some real music now. We got Johnny Whisnant playin’ the banjo with us” … and we’d go out and we’d do somethin’ big, then the name of the name of the band would go on there first and away down the line somewheres, my name would appear. Now this can knock a fellers ambition right out the window, you know.”

In addition to being an inventor, builder of fine banjos, and expert instrument repairman, Johnny is a competent music instructor, presently teaching banjo, guitar and bass fiddle. Among his current students are the Spence Kids from Herndon, Virginia, who just won third place at Warrenton (National Championship Country Music Contest). “The way I got into this teachin’ business … I was tryin’ to train myself a band.”

Johnny has received his share of criticism in recent years. “It’s been said about me . . . that I play from a chord … I do too much chordin’. It’s as simple as this … they don’t know what I’m doin’,. The reason they can’t understand what I’m doin’, they have played open string stuff, and started out playin’ open tunes … Earl Scruggs type things. Now I have learnt . . . way back when I was a boy, to play from a chord … to play my melody from a chord, and I’ve passed it on down now and I’ve used that as a back up . . . and I still do. There’s not enough action in the left hand to suit ’em, and because I don’t get all excited and jump from one end of the fingerboard to the other, they think I’m not doin’ anything . . . but I’m pullin’ the same notes they’re pullin’ . . . but I’m just doin’ it much easier.”

“Now this is the thing they don’t like. It’s not because they dislike me, or dislike the style that I play or dislike the sound that comes off my banjo … but it’s the fact that they can’t learn it, without bein’ taught from me. If they learn it, I have to teach it to ’em, ’cause they ain’t nobody else that does it that way. There’s nobody else that plays that way now … because the old banjo players like Clay Everheart, Oliver Webb and them guys … they’re all dead now.”

Some of Johnny’s critics claim he depends too heavily on his tuners. “I played the first contest around here in 1963, and I cleaned house. I didn’t clean house because I was that much better than anybody I played against. I was doin’ what I wanted to do and my cheaters played a part of it. I had a new sound, and I knew it and I knew I had a sound that the public would like … so I come up here and cleaned house in ’63. I won $720 in two weeks … in three contests. I had somethin’ brand new and I was playin’ that thing from the way I felt … and everybody got to talkin’ about me and said, “Well, you take his cheaters off his banjo and he can’t play a note.” Then they tried one time down at Warrenton to outlaw the cheaters … and I went in there and explained to ’em, I said the cheaters are as much a part of a 5-string banjo as the tuning keys are, in this day and age. As much a part as the bridge, you know . . or the frets. I got permission to use the cheaters, then I didn’t even use ’em in the competition. I played straight tunes and still won it.”

Other critics complain that he plays too loud, still others have called him eccentric. Johnny dismisses all this with a shrug. Once, when we were on this subject, he remarked: “Mebbe it’s because I don’t have guys like Carl Story, that believed in me … or like Charlie Bailey or Carl Butler. They all liked the rough person I am . . . because if you’d say, “Let’s go to Table Rock right now and spend the month,” I’d be ready to go.”

JOHNNY WHISNANT DISCOGRAPHY

Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers: Columbia

You’re Bound To Look Like A Monkey When You Grow Old/Careless Love/I Like Mountain Music/Gathering Flowers From The Hillside/Unknown Title

Fiddle – Carl Story

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Guitar – Ed McMahan

Guitar – Dudley Watson

Recorded in Atlanta, Georgia about 1937 NOTE: None of this material was ever issued.

Carl Butler: Capitol

6855 String of Empties. 1813

6856 You Plus Me. 1813

Shake Rattle and Roll. 1454

Ho Guareantee On My Heart. 1454

7093 Our Last Rendezvous. 1541

No Trespassing. 1701

I Live My Life Along. 1541

Linda Lou

Vocal – Carl Butler

Guitar – Smokey White

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Fiddle – Art Wootten

Dobro – Speed Krise

Bass – Jake Tullock

Recorded at Capitol Studios, Nashville, Tennessee in early 1951.

NOTE: Although the matrix numbers would indicate that the two Capitol sessions were at least several weeks apart, Johnny insists that both sessions were cut the same day. One mid-morning session and one evening session with a Jimmy Skinner session in between. Johnny, if fact, recalls participating in two numbers on the Skinner session.

The Bailey Brothers and the Happy Valley Boys: Canary

Bleeding Heart/St. Louis Blues

Guitar – Danny Bailey

Mandolin – Charlie Bailey

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Fiddle – Chubby Collier

Bass – Jake Tullock

Recorded in Raleigh, North Carolina, in late 1951

NOTE: Although the Baileys released versions of these two numbers, the material on this particular session was never released.

The Church Brothers and the Blue Ridge Ramblers: Blue Ridge

Unknown Title

Guitar – Joe Franklin

Mandolin – ? Church

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Fiddle – Ralph Pennington

Bass – Dean Walsh

Recorded at Drusilla Adams’ home, North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, about 1953. NOTE: Johnny doesn’t remember which of the Church Brothers participated at the session, nor does he recall which song they cut. He thinks it might have been “Way Down In Old Caroline.” He is certain, however, that the number was released.

Benny and Vallie Cain and the Country Clan: Rebel

New River Train/Ragtime Annie F-237

Guitar – Vallie Cain

Mandolin – Benny Cain

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Fiddle – Jimmy Delozier

Bass – Don Mulkey

Recorded at Capitol Transcriptions, Washington, D. C.

January 30, 1963

Somebody’s Waiting For Me/Whoa Mule Whoa F-238

Angel Band/Seeing Nellie Home F-243

Personnel – Same as above

Recorded at Wynwood Studios, Falls Church, Virginia *

June 20, 1963

It’s A Weary, Weary World/I Wonder If You Feel The Way I Do/When Springtime Comes Again/The Convict And The Rose/My Love Is Evergreen/Drifting And Dreaming/Home Sweet Home/Long Journey Home/Peacock Rag

Personnel – Same as above

Recorded at Wynwood Studios, Falls Church, Virginia June 30, 1963

NOTE: All of this material was included in the “Bluegrass Spectacular Package, 70 Songs,”a 4-LP package deal offered by Rebel Records about four years ago, and is the only place these numbers were released.

The Countrymen: Peak

Country Trumpet F-101

Virginia Feud. F-102

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Trumpet – Rick Gall

Guitar – Vallie Cain

Bass – Gordon Sturgill

Recorded at Rodel Studios, Washington, D. C. in 1964.

Al Jones and the Spruce Mountain Boys: Rebel

How The Story Had To End/Spruce Mountain Slide F-254

Guitar – A1 Jones

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Dobro – Pee Wee Fadre

Fiddle – Billy Baker

Bass – Frank Goolsby

Recorded at Wynwood Studios, Falls Church, Virginia, in August 1965.

Buzz Busby and the Bayou Boys: Rebel

Mandolin Twist/Blue Viet Nam Skies F-258

Guitar – Charlie Waller

Mandolin – Buzz Busby

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Fiddle – Billy Baker

Bass – Tom Gray

Recorded in Baltimore, Maryland, November, 1965

Benny and Vallie Cain and the Country Clan: Rebel SLP-1484

The Wolf Is At The Door/Grandfather’s Clock/No One Dear But You/Golden River/ Rheumatism Blues/They Laid Him In The Ground/Rover Rover/Johnny’s Rock/Is It Time/ Watermelon On The Vine/F-5 Bounce/You Don’t Love Me Like You Used To Do

Guitar – Vallie Cain

Mandolin – Benny Cain *

Banjo – Johnny Whisnant

Electric Bass – Paul Cain

Recorded at Roy Homer Studio, Clinton, Maryland November 3 and 10, 1968

APPENDIX:

Johnny’s reference to Dock Walsh stated that he might still be living. I have since learned that Dock Walsh passed away several years ago.

In Part II (July), pages 9 and 10 were put in reverse order. To read the article properly, after reading pages 7 and 8, read page 10 next, then page 9, and finally page 11.

Anyone wishing to contribute additions or corrections to any of the material presented, are welcome to write me at BU. Anyone wishing to contact Johnny may do so by writing: Johnny Whisnant, P. 0. Box 12, Ashburn, Va. 22011

CREDITS:

Most of the material in this article was compiled from a series of taped interviews with Johnny Whisnant in Herndon, Va. on 3/23/70, 3/24/70, 4/23/70, 5/22/70 and 6/29/70. Johnny also furnished most of the photographs used in the article. I would also like to thank Carl Story, who wrote a fine letter and sent me a rare photograph from his collection; Charlie Bailey; Gary Henderson; Benny and Vallie Cain; Tom Gray; Pete Kuykendall of Wynwood Studios; Dick Freeland of Rebel Records; and last but by no means least, Dick Spottswood. WVS