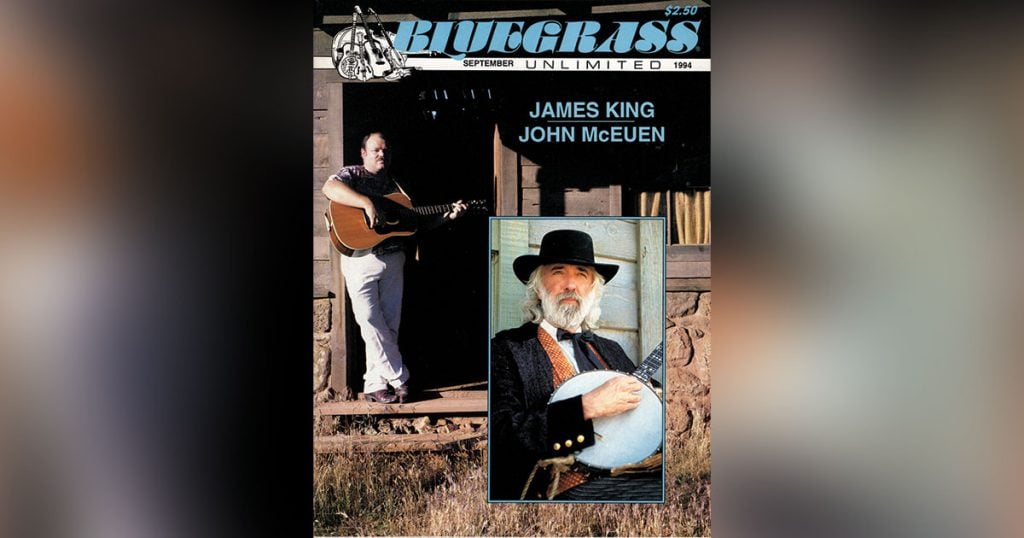

Home > Articles > The Archives > John McEuen—String Wizard & Media Producer Extraordinaire Of The 90’s

John McEuen—String Wizard & Media Producer Extraordinaire Of The 90’s

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1994, Volume 29, Number 3

When John McEuen appears at a bluegrass festival today, it’s obvious that he isn’t an entire bluegrass band—although he does move around a lot and play four different instruments. You can tell he’s one of the believers, though. The heart and the influence of what Monroe, Flatt, Scruggs & Company perfected in the 1940s is there inside John’s music—along with some much older musical roots, all presented with his own unique flair. And although McEuen may not be considered by most to be a mainstream bluegrass performer, he has been one of our strongest proponents, as far as exposure goes, through his acoustic influence in the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and through his current ventures into the production of music videos and film scores. His cut of “The Ballad Of Jed Clampett” on String Wizards II was also a Grammy nominee in the category of Best Instrumental Recording/1993.

“I’m proud of the fact that I’ve been able to get banjo and mandolin sounds on pop radio,” McEuen says, “and I like to bring what I do to bluegrass festivals because I like to perform, and I like to tell people where some of it has led me.” McEuen calls his current performances—either solo, or a duo with his 17- year-old son, Jonathan—“kind of a musical travelogue that covers the last 25 years.” The listener may hear material ranging from a straight-ahead bluegrass banjo tune to Travis-style guitar, double thumb frailing, or classical banjo. And interspersed between the songs, John sure has some good stories to tell, as he relates different songs to various periods of his life.

John McEuen got his first banjo at the age of 18. He was living in southern California, working at Disneyland as a musician and going to college. (One of John’s co-workers at the theme park was comedian, Steve Martin, another banjo player.) McEuen’s musical imagination was fired up by seeing the Dillards perform in the ’60s. He also lists early influences: Lightnin’ Hopkins, Doc Watson, Merle Travis—and Flatt & Scruggs. In 1966 a group of guys who hung out at McCabes Guitar Shop in Long Beach formed the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, with the intention of playing “goodtime music, for fun. ” In a long career that crossed marketing lines from folk to rock to country, the group has made 20 albums and played over 4,000 venues in the U.S. alone, and performed on all the television shows of the time—including opening for the Doors and Jack Benny. They were featured in the 1968 Paramount film, “Paint Your Wagon.” “Mr. Bojangles,” from their fifth album (1969), stayed on the pop charts for 34 weeks. They were also America’s first band to tour Russia, in 1977 for 28 shows.

Then in 1971 came the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” album—the platinum disc for United Artists that was the brainchild of brothers Bill and John McEuen. In this landmark recording the members of the Dirt Band were combined with some of the founding figures of country music: Earl Scruggs, Roy Acuff, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, Maybelle Carter, Jimmy Martin and Vassar Clements. If John has one comment to add about the “Circle” album, he says, “I want to make the point that Earl Scruggs was not just there—he made it happen. And Earl never has gotten enough credit. He got us in touch with Vassar Clements, Roy Huskey, Maybelle Carter, and helped us get in touch with Jimmy Martin. He made the album happen by giving us some connections, credibility, spirit and guidance—on top of his incredible music.”

Almost all gigs come to an end at some point, and John McEuen’s decision to leave the Dirt Band to pursue his own interests came in 1987. “The band didn’t really get into bluegrass. I was into it,” he states simply. “I was the guy shoving the acoustic instruments into the microphone as much as I could, trying to get the band to do more of the bluegrass stuff…My interest started to wane because the music wasn’t moving in the direction of what I wanted to be involved in. They didn’t want to record instrumental music anymore.” John’s response was, “Oh. Well, I’ve gotta go somewhere where I can.”

One of the recurring themes in a conversation with John McEuen, (also evidenced by his recent String Wizard CDs and various video projects), is his belief in the “magic” of instrumental music— its power to touch hearts and inspire the imagination. In fact, he calls Earl Scruggs the “Eddie Van Halen of country music. Have you ever listened to the old Opry tapes?” he asks. “Earl was the first time you could hear eighth notes. I figure that because of (poor) sound reproduction, you couldn’t hear the bass—it didn’t drive you and make you crazy. The lead acoustic guitar was almost nonexistent. Fiddles were always too much top-end and going around too fast, with the notes slurring together. The mandolin wasn’t playing a lot of single string leads that were real driving. And then here comes the banjo: ‘Chicka-chicka-chicka-chicka-chicka,’ and you could hear it from the back of the room. If he got anywhere near the mic, you could hear each individual note. It’s notes that make people crazy,” McEuen continues. “That’s why instrumental music is so important to me. It’s trying to find that secret combination of notes that allows people to make their own visual impression of what the music is portraying. I like instrumental music because ten people can listen to it and get ten different impressions.”

VIDEO WIZARDS PROJECTS

In his efforts to promote his musical ideas in the 1990s, McEuen has turned to television, with the production of music videos and musical scores for films.

A Night In The Ozarks is a 90-minute documentary of the Dillards, produced by McEuen. “I think it’s one of the most fun things I’ve ever made—it’s the Dillards at their hottest,” John comments. “And to me, they were one of the most influential in getting their music to a huge audience, and in turn exposing bluegrass sounds to those same audiences.”

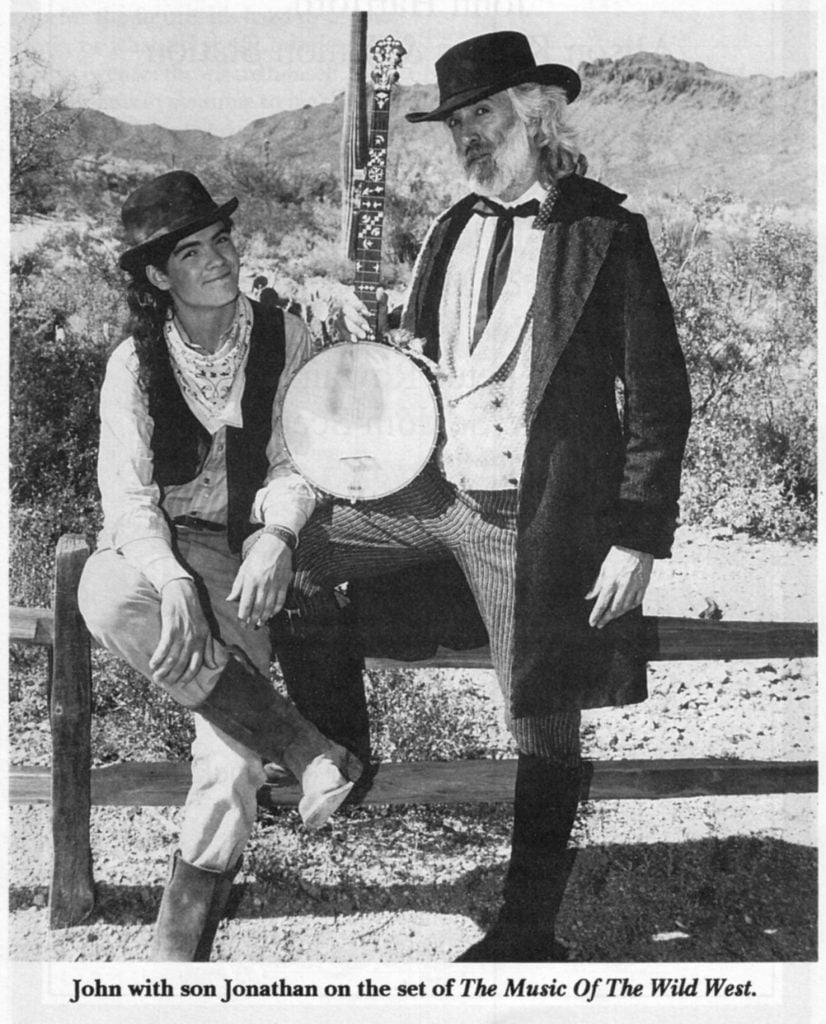

Music videos, “Return To Dismal Swamp” & “Miner’s Night Out,” cut from the Vanguard String Wizards CD, were both played in heavy rotation on CMT and were favorites on The Nashville Network. The latter was filmed in the historic mining community of Deadwood, S.D., with fully restored buildings circa late 1800s—early 1900s. “I tried to imagine what might have happened in a gold camp when the miners got together on a Saturday night,” McEuen said, explaining the origin of the song. “It would be the only night that some of them came into town, and they would be ready to have some fun: play a little music… dance a few jigs… participate in a couple of card games.” The cast of nearly 200 included Deadwood residents in period costumes, along with John and Jonathan McEuen playing banjo and guitar with the band.

In conjuction with “Miner’s Night Out,” McEuen made a television commercial for the city of Deadwood, advertising it as a tourist destination. The piece, which won a Silver Star award at the Houston Film Festival for Best Regional Commercial, also helped finance the music video. And of course the town got extra PR mileage out of the music video.

In March 1993 The Wild West, a 10 hour mini-series produced by Warner Brothers and syndicated by Lorimar, aired on Prime Time Entertainment Network, with 250 minutes scored by McEuen. John drew from traditional music, as well as original compositions, recording 98 musicians in 15 cities. The score combined the heritage of all America: the native American, Irish, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Scottish, German and African American. “I was trying to reflect what was in the West, in America during that time period (1865-1899),” McEuen explained. “What that means is primarily stringed instruments being played by people in their homes or around at dances, or brass bands.” (The series reran in December 1993.)

Time Life has now released the mini-series in a video collection, in conjunction with a 352-page coffee table book.

A CD released by Mogull Entertainment also came out of the mini-series project, along with another television special scripted and scored by McEuen for the Nashville Network, both entitled The Music Of The Wild West, (September 1993, with two reruns later). Well-known country artists Gary Morris, Crystal Gayle, Marty Stuart, Mary Macgregor, Michael Martin Murphey, Red Steagall and McEuen himself performed on these projects—backed by folks like the Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, the Americus Brass Ensemble, and Colcannon, among others.

The Nashville Network special begins with a stagecoach coming into town. John is talking to his son, Jonathan, about a school assignment he has—a report on “What was important in the Wild West.” So they proceed back in time to 1885 and find out, firsthand, about the music of that era. Performances take place in the saloon, in a graveyard, on a porch, and out on the prairie, McEuen says. “The set-up is an ‘over-zealous father going further than necessary to help kid with his homework,’ ” he laughs. “The music is my form of bluegrass—I don’t know what it is—maybe ‘oldgrass.’ ” Two other McEuen sons, Ryan and Nathan, also appear in this film as a bank teller and an opera house ticket taker. Marty Stuart plays a burned-out miner, Michael Martin Murphey plays outlaw Cole Younger, Jennifer Warnes is a school marm, and Crystal Gayle appears as a theatrical singer.

Another special of the same theme, this one for radio, was produced by Great Empire Broadcasting for Mogull Entertainment. The Music Of The Wild. West, hosted by Johnny Western and Orin Friesen, is a one-hour show produced in four segments for commercial radio, available on CD. Friesen interviews McEuen, Murphey and Stuart about the soundtrack album and the music of the Wild West; and selections are played from the project.

McEuen’s other most recent scoring projects include a PBS special for National Geographic called Braving Alaska, and The Man Outside — starring Levon Helm and Bob Logan, for HBO/ Cinemax. (Vince Gill sang the title song.) “Alaska” won four international film awards as well as the New York Film Commission Award for Best TV Special. It was PBS’s highest rated show in the first quarter of 1992, and was submitted for Emmy nominations in five categories, including music.

McEuen also produced a 4-camera shoot of the Tennessee Banjo Institute, an event held last year in Murfreesboro that drew 300 banjo players from all over the world.

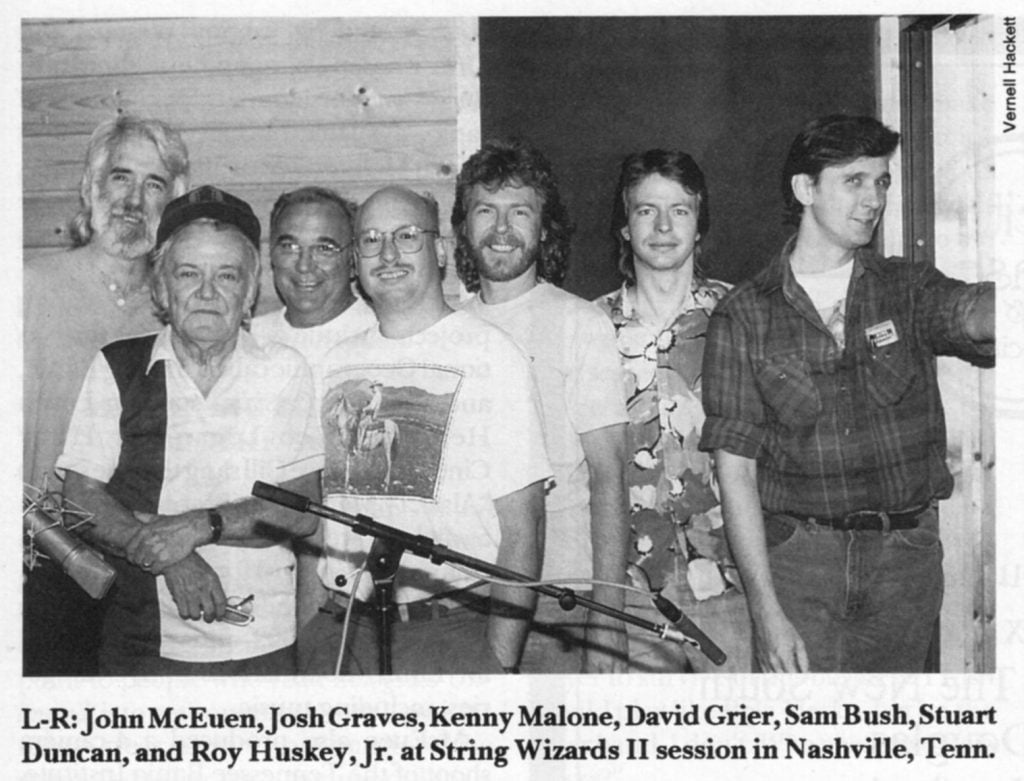

“String Wizards,” McEuen’s critically acclaimed CD on the Vanguard label, was followed last September by “String Wizards II.” The original “wizards.” McEuen, Sam Bush, Stuart Duncan, Jerry Douglas, Roy Huskey, Jr. and David Grier are joined by special guests David Grisman, Darol Angor, Rob Wasserman, Tony Rice, Byron Berline, Jose Feliciano, among others. The project “reflects traveling around the world,” John explains. “One cut reflects Russia, one—New York City, one—San Francisco, one—LA, one—Phoenix. And on the bluegrass side, ‘Groundspeed’ is on there because it refers to traveling, and ‘Redwing’ is on there because I like it.” And like the first Wizard CD, there are the unusual arrangements and sound effects. At one point you hear a car door slam, the sounds of an airport, customs, and then take a cab ride to a Mexican restaurant that sounds like a Tijuana bar. And there, evidently, McEuen and Berline join the band onstage for a rousing rendition of the “Jesse Polka,” noisy crowd and all.

These unusual effects shouldn’t surprise those of us who still have NGDB albums stored away in our closets. Remember the waterfall on “Ripplin’ Waters,” on the “Symphonium Dream” album, and the intro to “Bojangles?” Uncle Charlie tries to coax his dog Teddy, who is under the bed, to sing “The Old Rugged Cross” in soft howls.

John credits his brother Bill with the Uncle Charlie concept, and also with getting the “Circle” album accomplished. “Bill took this little ball I’d thrown out on the field, assembled the team and won the game!” McEuen recalls. “Bill was always the visionary who would focus in on the idea and see it to fruition.”

MARKETING BLUEGRASS IN THE ’90s

From a unique perspective and experience, John has several ideas for bluegrass bands in the ’90s who want to take advantage of modern entertainment technology and business know-how. “My point to people who read Bluegrass Unlimited, is to get your music out there in as many areas as you can imagine,” he states, “whether it’s a commercial for a local business, or putting something together that tells a story with acoustic instruments. There are additional ways to get exposure for your band. Don’t just depend on radio (alone).” Here is some more of McEuen’s specific advice:

- “One thing that is being overlooked is children’s music… I think some bluegrass group should make an effort to hit the below-10 level of the children’s market, because the kids usually like the music and the sounds of the instruments at that age. Riders In The Sky are a good example of how well that can work for you. Plus—you play to the kids, and in 10 years you’ll have an audience that’s coming to see you. And besides, it’s a good service.”

- “Find someone who’s interested in shooting a video on your band, and make a neat 8-10 minute video press kit. Include the history of the band, performance footage, a voice over to describe what the band is known for, quote some reviews, and use some music off of your album.”

- “Find out about how commercials are made and how music is put to pictures—explore that and figure out what SMPTE time code is and how to use it.” (The computer code that locks pictures and music tracks together.)

- “Find a logo for your group that you intend to use all the time. Look at good examples, like (the rock band) Chicago. There are so many things to look at these days, you have to be easy to find. In a record store you have 15 seconds until people change their minds.”

- “Be critical of what you do, make sure it’s your best effort and keep at it.” But then again he adds, “Take your work seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously. Just work hard and do the best you can.”

- “Don’t be afraid to take chances. The worst thing anyone can say is ‘No.’ I was scared to ask Roy Acuff to be on the ‘Circle’ album, and he said ‘Maybe.’ ”

- “Don’t leave all the responsibility for lighting and sound to the club. Light the stage up. If you can get people to look at you when you’re on stage, they’ll listen to you.”

- Lastly, “Make your music an original version. You don’t have to be the best player to survive in this business. I wish I could play like Bela Fleck—but on the other hand, I don’t. Who needs two Bela Flecks?”

As for the future, it’s hard to predict magic, or what the music business will bring—even for the wizard himself. John says he plans to continue to make CDs, and he would like to take a group on the road at some point. He wants to continue to develop the music ofhis son, Jonathan, and work with him. “He’s one of my favorite musicians and singers,” John comments. “He can play hot blues guitar, but he also understands ballads and certain types of acoustic, country-based music.”

McEuen is considering a move to Nashville in the future, and he would also like to continue to make more TV shows and film scores.

And John would like to play more bluegrass festivals. “What I did in the Dirt Band is only 20 percent of what I can do,” McEuen states, “and I think some people were judging that as all I can do…I’d like to be able to come show them the rest.”

Who knows in what venue the Wizard will pop up next, with his own unique brand of acoustic arrangements and material. We’ll be watching and listening.

Nancy Cardwell is a freelance writer and musician living in the Branson, Mo. area. She plays bass for Midnight Flight bluegrass band, she also performs in a hammer dulcimer duo, and with an a capella quartet the Coventry Carolers.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Where can I get a copy of the tv show music of the Wild West written and produced by John mc Euen featuring Jennifer warnes as a school marm singing dreary black hills