Home > Articles > The Archives > John Hartford: Living His Dreams

John Hartford: Living His Dreams

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June, 1985. Volume 19, Number 12

The photograph John Hartford considers his favorite tells a lot about the man. It depicts him standing between two of the biggest influences on his life, Earl Scruggs and his fifth grade teacher, Miss Ruth Ferris.

You also need to know about his modesty. Listen: “I do the best I can and that’s how it comes out. I believe that style is created by limitations. My limitations are what define my style. My art is a struggle for me to reproduce the sounds I hear inside my head and communicate them to you the listener. Let’s just say I’m always trying to overcome my limitations and I would say that one of my limitations to me is not being able to pick any better than I do, and I’m always working on that. I think my life is working hard at getting better at doing what I do.” That from the man who wrote “Gentle On My Mind,” which at over 3,000,000 has the most number of performances of any BMI licensed song.

You also need to see the sparkle in his eyes on stage, and the knowing smile as he picks, fiddles, dances and sings to the delight of audiences in every sort of venue from Japan to Europe. When he’s finished a show he likes nothing better than to cut loose on the fiddle and call a few square dance figures for the crowd.

Dance music and fiddle tunes run deep in Hartford’s life. “My parents used to square dance a lot, sometimes to live music and sometimes to records and stuff like that.”

So Hartford grew up in St. Louis involved with both music and his work on the river as a teenager. He learned to play mandolin, banjo and fiddle. “The band that I first saw that really turned me around and made me really want to do it was the Foggy Mountain Boys with Earl and Benny Martin and Curly Seckler and Lester. As far as actually patterning myself and learning to do what I do now my big inspirations and the people that really influenced me heavily were Earl Scruggs and Benny Martin and other people of that era. Bill Monroe. I went through a really intense period of studying the Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt and Benny Martin sound. I’m still very much taken. That was the sound that really got me going and I would say that what I do comes as much from that as anything.”

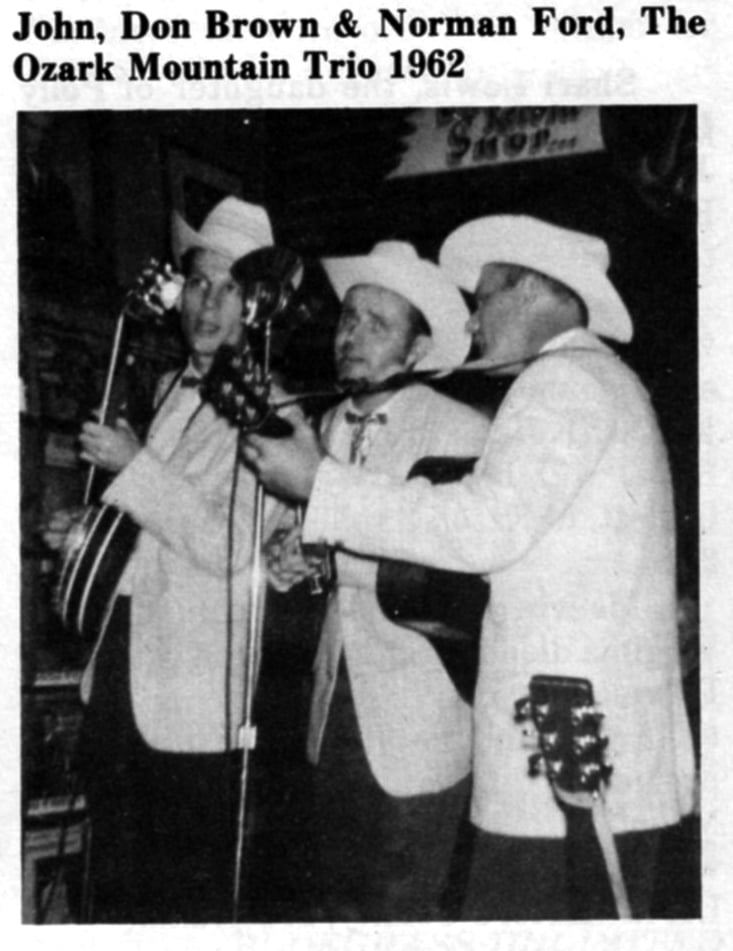

During the late ’50s and early ’60s Hartford bopped around the Missouri- Illinois area working as a record promoter and disk jockey. He sat in with many local groups. In 1958 he became the original banjo picker for Don Brown and the Ozark Mountain Trio (see BU October 1982). He also picked with the Missouri Ridgerunners and a band called the Dixie Ramblers that included Doug and Rodney Dillard.

“I think I was a senior in high school or my first year in college when I met Douglas [Dillard]. Marvin Hawthorne and Clifford and Gene Goforth and I and Don Brown went to see a Lee Mace show with the Ozark Opry in St. Clair, Missouri, and Douglas was up there. We started hanging around together a lot around St. Louis. Rodney was going to high school in Salem, and he used to come up and sit in with us.”

Eventually Hartford got a job at WSIX and moved to Nashville. He landed a songwriter contract with the Glaser Brothers, who convinced RCA records to sign him. “They thought I would be their Bob Dylan.” Hartford began working as a solo performer for the first time. “I played a little bit on the fiddle and a little bit on the guitar and the banjo, but I mostly just sat on a stool and sang my weird songs. I was really into being a singer/songwriter in those days, so I mostly sang these long introspective songs that I wrote.”

He recorded six albums for RCA through 1971. A single entitled “Gentle On My Mind” moved far enough up the country charts in the spring of 1967 that Glen Campbell happened to hear it. His smash hit version of the tune catapulted Hartford toward celebrity status.

Bill Thompson, then program director for a major country radio station in Los Angeles met Hartford through Jan Howard. “He took some of my albums and gave them to Tommy Smothers. Mason Williams listened to them and liked them and told Tommy that he should check into me. Tommy called me up on the phone and prepaid me a ticket to Los Angeles to come out there and meet him.”

Thus, with no prior experience, Hartford became a scriptwriter for the Smothers Brothers TV show and the Glen Campbell program that it spawned. He also appeared on camera. “We even ended up taping at the same time, and I’d run across the hall between the two studios, doing both shows. Pretty heady times.

“It didn’t appear to be disruptive because it was a real ego trip. I would say creatively it was quite disruptive, especially ‘Gentle On My Mind.’ I’ve still never figured out why my creative output went way down after that song won all the awards. It was very strong before the song did what it did… In fact, I hadn’t really begun to get that creative output back until I started to work with Jack Clement. Then it really went into overdrive.”

Hartford’s output has returned in full force. “Mostly what I’ve been writing these days has been fiddle tunes, but I’ve been writing quite a few songs and finishing a few. I’d say maybe one a day. Usually what that means is a title and a melody and a few lyrics. I don’t say I finish that many songs. Actually, it’s very hard for me to finish.”

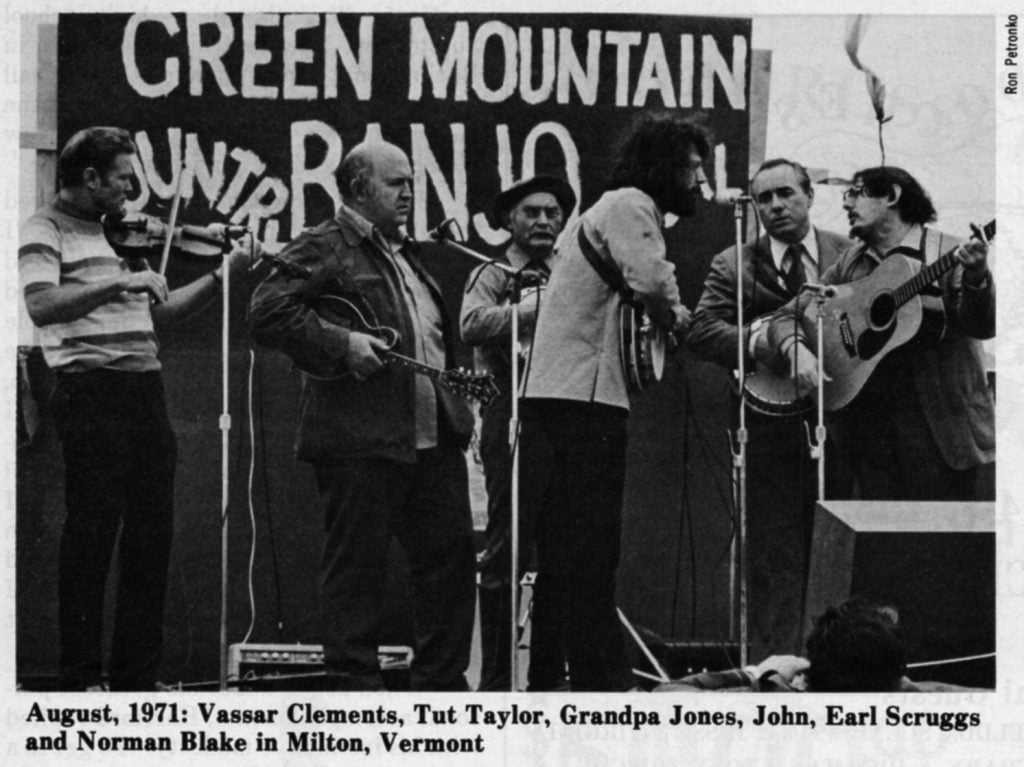

In 1971 Hartford changed labels from RCA to Warner Brothers. The move signaled a shift from the folky singer/songwriter guitar and strings approach of his previous albums to his most overtly bluegrass period. He assembled a remarkable band of Norman Blake, Vassar Clements and Tut Taylor and hit the festival circuit. The four repaired to Glaser Sound Studios to cut the tour-de- force “Aereoplain” album. It remains the oldest John Hartford album still in print.

The next year Blake and Hartford toured as a duo and recorded a second Warner Brothers long player, “Morning Bugle.” The record marked the end of his major label career. “In two weeks it didn’t sell enough to meet some kind of sales quota. They stopped mailing them out and promoting them, and nobody could get them. I went to Joe Smith and asked for my release, and he gave it to me. So then I spent three years where I didn’t record for anybody.”

Hartford hardly wasted that time, continuing to perform and advancing his other career as a riverboat man. “I’ve always been into the river. When I was a kid I was real lucky and got into the last of the steamboat era with the Golden Eagle and the Gordon C. Green running out of St. Louis. When I was fifteen years old I got a job on the river. I worked on the Delta Queen, and I worked on tow boats awhile. I was away from the river for a while, but I realized that I had to have some river in my life somewhere just to keep my head straight.”

It took Hartford three years to earn a 100 gross ton passenger boat operator’s license for inland waters. For twelve years he has spent about ten days a month between Memorial Day and Labor Day as a pilot on the Julia Belle Swain out of Peoria, Illinois.

“I’m a regular working pilot. What we do is the first day I stay in the pilot house the whole day, because these are two day trips.

Then that night we stay at the Starved Rock State Park Lodge. We usually have a jam session at the lodge and I play that night. Then the next day on the way back I go down and sit in with the house band and do a couple of numbers. And, of course, we have friends that come on the boat now, and we have shows on the boat. Bryan Bowers, the Dillards, New Grass Revival, and people like that have been on the boat.”

The river also acts as a musical inspiration and point of reference for Hartford. “I’ve tried to collect songs that I think are river songs for one reason or another. There’s a certain element of music which seems typical of the river area. Actually, I would say, old-time music and the fiddle and the banjo is really very much river music going all the way back to the flatboat days. The old flatboats and keel boats and raft boats that floated the river all carried a fiddler as part of the crew for morale and to ease the work load. A fiddle tune and a little bit of whiskey could keep a man on a pole for a long time.

“Also, there seems to be evidence now that the banjo actually got back into the mountains by way of the river. In the old days a lot of the mountain entertainment was the circus, and every circus carried a minstrel show, and the minstrel shows all had banjos. This is prior to the War Between the States, back before the railroads came in, and the only way they could get anywhere was by river. The circuses were called boat shows, and they traveled up all these tributaries with their minstrel shows.”

The river provided the subject matter for Hartford’s first album upon returning to the studio, “Mark Twang.” That record marked the beginning of his association with Flying Fish Records, which has now issued ten of his albums. “I got to know Bruce Kaplan, and I liked his operation, and we did an album with Benny Martin, and I liked the way that was handled, so I went with him. They keep my albums in print. I’ve always had pretty much artistic control.”

Hartford expresses special satisfaction with his latest album, “Gum Tree Canoe,” the product of a year and a half long association with producer Jack Clement. Clement, a on-time Sun Records rockabilly, is best known for his work as a writer and producer for Johnny Cash. “It’s been a wonderful creative experience. He’s taught me as much about recording as I’ve ever learned from any one man. So many songwriters, players, singers, producers and creative people have come along under his guidence. I feel myself extremely lucky just to have gotten to work with him. I certainly think this record I’ve done with Jack Clement is technically and aesthetically better than form and do quite the things I do when I’m by myself.”

Alone Hartford has full range for the spontaneity that makes each performance a unique interaction between artist and audience. “I don’t ever try to do anything like I did it on the record. I don’t try to change it just to be changing it either, but it all evolves. So when you hear me do a song live, you’re not getting a repetition of something you already have on record. You’re getting the next step. I think records really are photographs of the artist and the song at that point in their development.

“The songs I do on my program divide up into three categories. There’s the songs I like the best, the songs they [the audience] like the best, and the songs we share. Hopefully, there’s enough songs that we share to make it all worthwhile. There’s a happy medium, a pacing, to it all.”

Solo work helps with the travel since his entourage generally consists of himself, his wife, and two drivers. Although he works 150 to 200 dates a year, Hartford spreads them out so that he can spend plenty of time at home. “We don’t go out and stay out. Most of the work we do is in the midwest. We’re out three or four days, and then we’re in two days, and then we’re out two days and in three or four days. I think balance is the most important thing. If I cut down on my road schedule, I don’t cut out a great big chunk. I cut down in a pattern, an overall pattern, so that everything is in balance.”

Besides bluegrass and folk festivals, Hartford plays almost the full gamut of venues. He offered his March 1984 tour of the northeast as an example. “The first night we did a club, which was the Bottom Line in New York City. The next night’ we played Boston. We played Sanders Hall at Harvard University. The next night we were in North Hampton, Massachusetts. We played a coffeehouse. The next night we were in Hartford, Connecticut. We played a high school auditorium. The next night we were in Burlington, Vermont, played the city hall auditorium, put on by the mayor, and the last night we were in Jackson, New Hampshire, and we played a ski lodge.”

Recently Hartford has discovered the pleasure of mingling with his fans. “I just went out in the middle of them and sat down after the show and just started signing autographs and meeting people and everything like that. Kind of like what I heard Ernest Tubb used to do, and I really admired. The other night I did that, and I just stayed there and signed and talked and signed and talked until finally there was one person left, and I signed and talked, and then pretty soon he drifted away. I looked around me and there was a great big empty room. I thought, ‘Far out. Everybody got what they wanted, and they left.’ ”

When asked about his greatest personal accomplishments, Hartford replied with his instinctive modesty. “To get to a point where I’m able to get to know the people whose music I studied and followed on my way up. I’m kind of what you could call sort of a groupie, who has come’ into it from the artistic side of it. I’ve always wanted to know them better and understand their art more. How they created, and what they do, and how they do it, and to get to know them better and see that from the inside and even participate in it a little bit has probably been my most exciting accomplishment.”

After a quarter century in the music business Hartford is by no means ready for the old folks’ home or even the old home place. “I’m not ashamed of how old I am. I feel kind of good that I’m in as good a shape as I am. And I don’t believe for a minute that being 47 years old somebody has to be considered past their prime. I refuse to acknowledge that piece of information. I think I play better than I ever have, so I don’t feel there’s any reason why I couldn’t learn to play even better than I do now. I don’t consider myself a very good player, but I certainly consider that I’m improving, so at least there is some hope. I don’t believe in retirement.”

And who would want to quit when you’re living your dreams. “I’ve always known what I wanted to do since I was a kid, which is pick a banjo and be a steamboat pilot. I’m living those things out.”

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Getting to read about John Hartford and see where he came from makes me appreciate him more. The fact that he made “GOMM” a magnificent piece of work will keep him relevant til the end of time. I love his work. Thank God for giving us John Hertford.

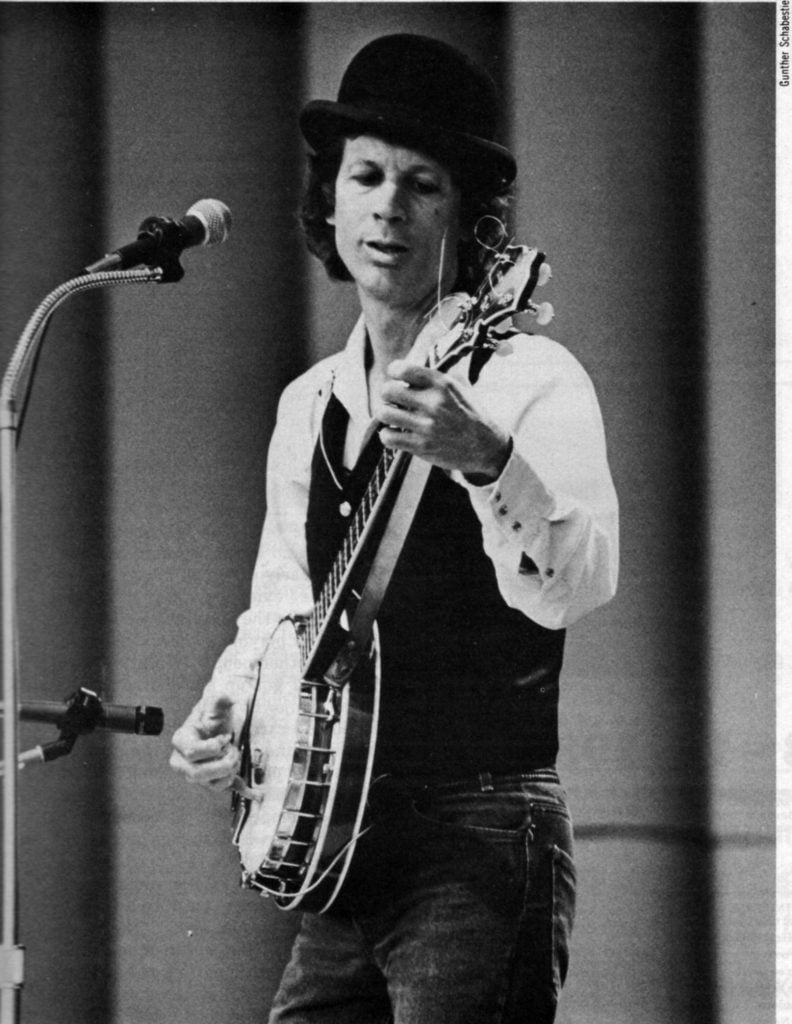

The best luck I ever had was to walk out of a restaurant one night in Hartford, Connecticut, cross the street into Bushnell Park and see John Hartford play unaccompanied for 90 minutes in the open air as night fell. I was fortunate enough to be about 20 feet away from him the whole time. His accompaniment was a 4 by 8 piece of plywood on which he tapped out the rhythm with his feet. His dress was black pants, white shirt, black suspenders and a bowler hat. His playing while singing was amazing, never missed a note, and introduced his songs as you would an old friend. After about an hour he put down his banjo, picked up a fiddle, placed it on top of his bowler hat and continued to play ten or more songs while tapping out the percussion for another half hour. It was an amazing performance by a man who devoted his whole life to music and the ways of bygone days. Thanks to John for sharing your gift with

us, I will never forget it.