Home > Articles > The Archives > Jody Stecher and Kate Brislin

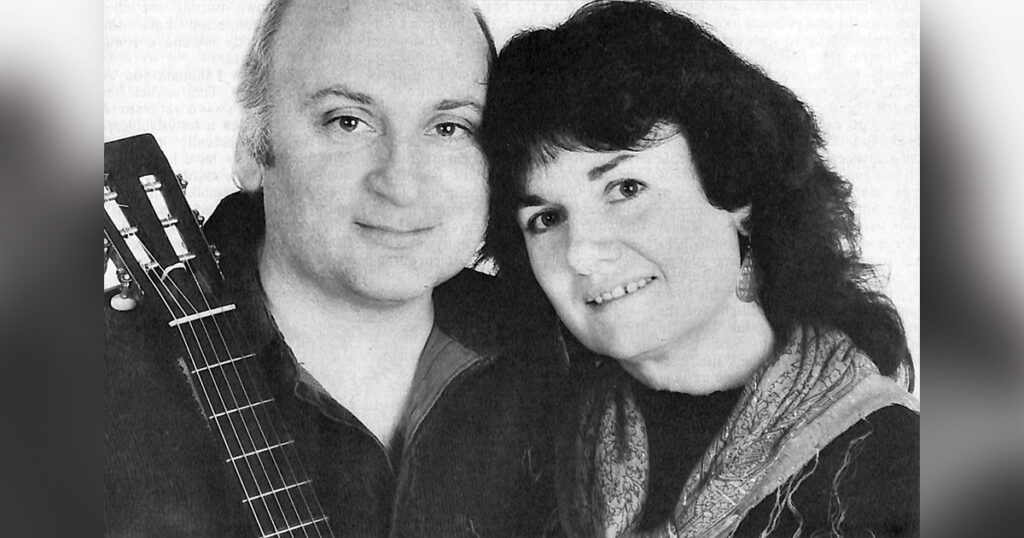

Jody Stecher and Kate Brislin

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1990, Volume 25, Number 5

When I first saw Jody he was sixteen, riveting everyone at a folk concert with his singing. I remember thinking at the time, “He sounds good enough to be a PROFESSIONAL.” In the years to come I got to know him and share his enthusiasm for bluegrass and all kinds of other musics.

Jody converted me to traditional music. I had a local bluegrass radio program, and he’d clearly let me know what he thought was the best material to play. Whenever I made a factual mistake on the air, he’d call immediately with the correct info.

He scared me a lot as a musician then—clearly some kind of traditional music genius in the body (and vocal chords) of a boy from Brooklyn. But Jody was an accepting musician too and I felt flattered that he’d want to play with me. He showed me that it was OK to go out on limbs for the sake of expression, that music is not so much to show off technique as to express joy.

But as far as technique goes, Jody is in a class by himself. He has played with his friends, those many musical instruments from fiddle to sursringar, for so long, he can make them talk! It’s a privilege to share my affection for Jody and his wife Kate and the music they make, with BLUEGRASS UNLIMITED readers.

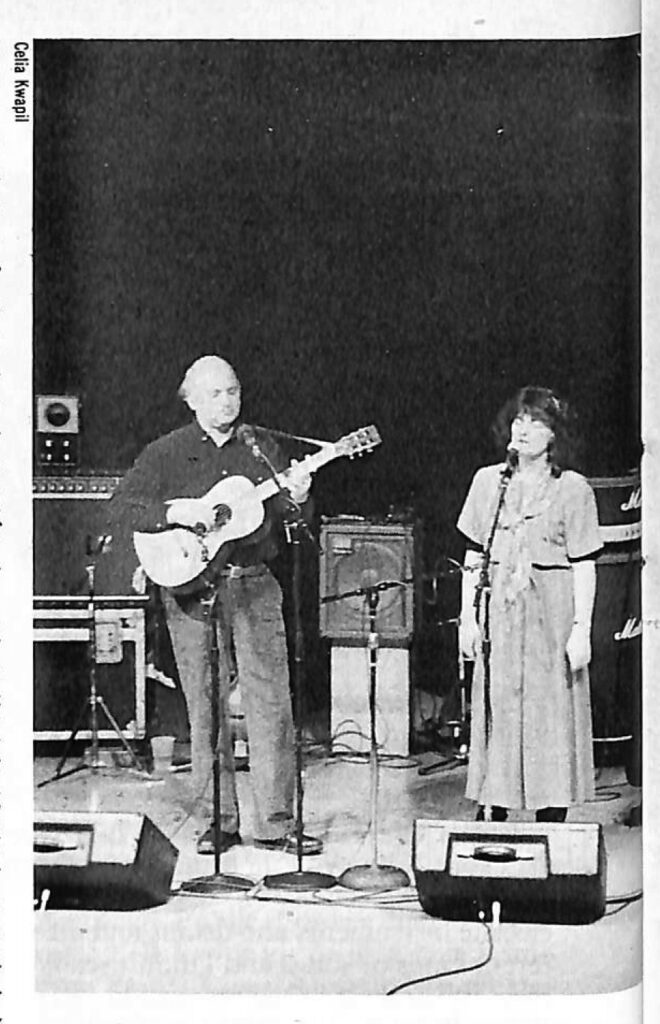

Tuesday, September 19, 1989, Owensboro, Kentucky. It’s the first evening of showcases at the IBMA World Of Bluegrass Trade Show. So far tonight several four-and five-piece bands have presented an attractive variety of bluegrass styles to this elite audience consisting mainly of professionals involved in the business of bluegrass.

The group taking the stage now looks a little out of place at first. It’s a duet, a man and a woman in their 40s, moving an interesting variety of in small old Martin guitar, a carved top A-model mandolin, two banjos—a fretless open-back and a new Gibson Mastertone and a fiddle.

It’s Jody Stecher and Kate Brislin, having traveled from San Francisco to introduce themselves and their music to this influential bluegrass audience. The blurb in the looseleaf describing the showcase acts refers to “Jody’s highly individualistic guitar style” and “wild inventiveness” and Kate’s “expressive and hypnotic vocals.” As they seat themselves and start adjusting microphones, one might wonder just how this shy and pleasant looking couple might live up to such descriptions.

From the first notes of “The Lover’s Return,” the audience falls silent and becomes absorbed in the music. The vocals are precise and intense, with an undercurrent that is indeed hypnotic. On the quieter number, the instruments are played with a sense of care and control that can come only from years of loving the experience of music making. On the livelier numbers Jody lives up to his billing as a master instrumentalist, playing virtuoso licks that sound like no other guitar player. He conveys no strain but instead a visible, unabashed delight in his own musical expression. Highlights of the set include the heartbreaking “Shut Up In The Mines At Coal Creek” and a powerful “Elk Horn Ridge,” their harmonies soaring high over driving twin banjos.

For the small proportion of the audience already acquainted with Jody and Kate, this performance is especially satisfying—one of the highlights of the week in Owensboro. It marks the surfacing of two important talents within a world that has been unaware of them for too long. When the set is over, a warm, sustained applause shows that bluegrass people fully appreciate sounds rooted in another era but recreated fresh in the moment.

In weeks and months to come, the circle of fans of Jody and Kate will widen as their first Rounder release, “A Song That Will Linger,” is heard and appreciated. County Sales Newsletter calls it “a superb job” with “each cut beautifully done.” The bookings on the bluegrass circuit begin to come in and bluegrass fans can now look forward to hearing this unique duo in person with some regularity.

While Kate’s performing background is mostly in old-time music, Jody’s has ranged literally all over the globe. After devoting himself almost exclusively to bluegrass music as a teenager, he spent years studying East Indian sarod and vocal music, middle eastern oud and traveling the world with such diverse partners as Scottish fiddle wizard Alasdair Fraser and the brilliant Indian sitarist Krishna Bhatt. Now, 25 years after winning his first trophy at Union Grove, North Carolina, he finds himself returning comfortably to the bluegrass scene.

Kate, a veteran of several old-time music bands, including Any Old Time and Blue Flame, was making one of her first appearances at a major bluegrass event.

“I was elated by the acceptance we received from the bluegrass community. I realized that the bluegrass audience really appreciates good singing. Jody plays hot licks and everything, but our focus is singing and bluegrass people are tuned into that more than say, an old-time crowd that might mainly like our fiddle-banjo duets. So for us, I felt like it expanded our connection to that whole world and makes me want to do more of it and be around those people again and go to bluegrass festivals. Our music has to do with the roots of bluegrass and I felt like we were perceived that way. We were accepted. It was most encouraging. What we try to present is where bluegrass and old-time meet. It has elements of both.”

Jody Stecher’s connection with this music goes back to about 1957. Around that time, the eleven-year-old became interested in a guitar lying around the house. Both parents were teachers and “My mother said I had to learn to play something, to play music. We would travel a lot in the summertime. And my father and I got on this instrument hunting thing. It started when we accidentally stopped in an antique shop and I found an old fretless five-string banjo. I was thrilled, because I liked the sound of a banjo. I was always trying to make my guitar sound like a banjo. My mother had these old records, a series of reissues on 78s called ‘Listen To Our Story.’ It had Dock Boggs and Buell Kazee and Uncle Dave Macon. Dock Boggs was the guy who got me. Oh man, I really wanted to play ‘Pretty Polly’ like that.”

Not an unlikely scenario for the early years of someone later to be featured in this journal. What makes it unusual is that this scenario took place in Brooklyn, New York, at a time when bluegrass and old-time music were virtually unknown outside the south. Something connected back then, though and Jody became a country singer.

“That’s how I thought you were supposed to sing. That’s what I was listening to. There was a station in New Jersey that played a lot of bluegrass and I could actually get WSM sometimes. I may have been hearing the Stanley Brothers when I was about twelve or something. I also listened to country radio. I liked some rock ‘n’ roll, too, but especially the country-flavored stuff like the Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry.”

He soon made contact with other budding bluegrass musicians in the New York area. Naturally these were rare, but in an area of over 15 million people, there were enough to form bands.

“My cousin, Jay Feldman, was in Brooklyn’s first bluegrass band, called the Kings County Outpatients. And I formed a band with some of the kid brothers of the guys in that band. I was a kid cousin. They called us the Little Outpatients. I took Jay’s place a couple of times. That was a big thrill.”

Jody studied bluegrass anyway he could. One of the Outpatients came home from college with “all these tapes, incredible things taken from the radio. A lot of Jim and Jesse and Reno and Smiley in particular.” Bluegrass performers occasionally ventured north at the time and to hear them Jody would find his way to the Newport Folk Festivals in Rhode Island, and Sunset Park, a true-to-life country music park only 150 miles away in eastern Pennsylvania. “I listened to the radio late at night. WWVA every Friday night and the Saturday stuff. The radio riveted me.”

At age fourteen, he started going to Washington Square, a park in Greenwich Village where folk musicians would gather on Sunday afternoons. At the bluegrass jams there, Jody soon became a central figure. He could hear all the harmony parts, knew the words to countless songs, played several instruments well, but above all, he was a convincing bluegrass singer. You could hear the influence of Monroe, Flatt, Seckler and especially Ralph Stanley, but the voice was a unique one and . . . convincing.

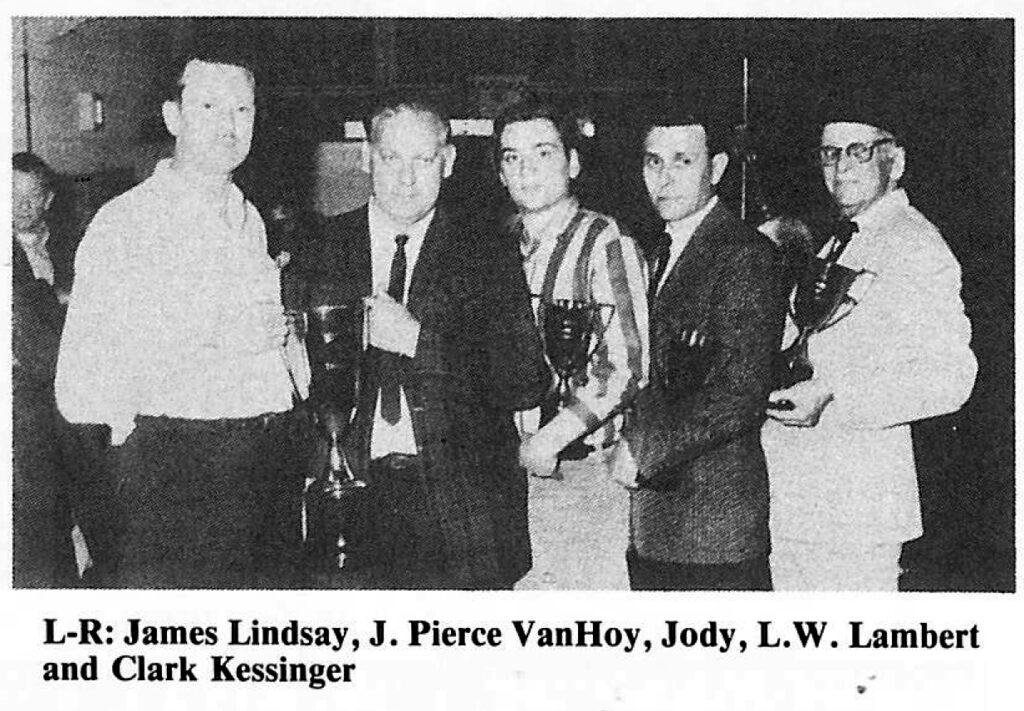

The Washington Square scene brought Jody into contact with many fine musicians, some of whom later went on to stints with Bill Monroe or to other notable musical careers (David Grisman, Steve Arkin, Gene Lowinger, John Sebastian, Winnie Winston, to name a few). Joining forces with them in various combinations yielded some of the city’s leading bands: the Down State Rebels, the Bluegrass Straphangers and the ever-changing New York Ramblers, a unit that went to the Union Grove, North Carolina, Fiddlers Convention every year from 1964 through 1969 and came back with trophies every time.

Though his main instrument was mandolin, Jody usually played guitar at Union Grove. “Mostly when I went down there, David Grisman was playing mandolin and I was taking breaks on guitar. In those days, very few people were playing lead guitar. The crowds went wild over our band, over the guitar playing, the whole thing. I’ve never seen an audience react like that.”

To many New Yorkers, the triumphs of the New York Ramblers in the south seemed to prove a point. But Jody “really wasn’t thinking that way too much. To me, it was completely normal that I should be playing this music. I’d been playing it since I was twelve. What I really liked about going down there was hearing the other bands. I enjoyed playing, it was nice to enter the contests and all that, but I spent a lot of time wandering around listening to other people. I loved the fiddle players. And the mix of old-time and bluegrass music. The borders there weren’t so clearly defined as some people would like to make out now. A lot of the old-timers, players over 70, quite enjoyed bluegrass music. They’d come up to me and say, ‘I really liked what you did. I liked your singing,’ or whatever it was, which made me very happy. I heard a lot of good players there.”

Other highlights of Jody’s early bluegrass years included appearances at folk concerts at Carnegie Hall and the summer following high school graduation, touring with the Greenbriar Boys, then a hot act on the folk music circuit. (His stint was between original mandolin player Ralph Rinzler and Frank Wakefield and included a spot on the network TV show Hootenanny.) One of Jody’s groups was even “discovered” by pop star Bobby Darin, who produced an album of their music which was never released.

But as often happens with young talent developing within a single tradition, other pastures beckoned. In the “melting pot” of New York City, many explorations were possible. “When I was too young to go into the city myself to go to concerts at places like Asia House, my mother used to take me to hear Ravi Shankar. She had a friend who was studying Indian vocal music and a couple of times I went to his lessons, and I was very impressed.

At the time I had already played with the Greenbriar Boys and been paid well and I thought I was pretty good. This teacher was the most accomplished singer I’d ever heard. He could sing anything. He sat on the floor and sang a very simple scale. I was awed by the way he sang such a simple thing with such complete devotion to the music and such humility. He was so childlike and completely serious at the same time. The combination left me dumbstruck.”

As a student at City College of New York, he had the opportunity to study the folk music of other countries, including a trip to Mexico with several other students and a teacher to study the music of the Tarascan Indians. The same summer, he and a friend borrowed a top-of-the-line portable Nagra tape recorder and went to the Bahamas to find legendary guitarist Joseph Spence and record his music for Nonesuch Records. And that wasn’t all.

“I always loved Cajun music. The Brooklyn Public Library had a great record. It had a lot of different musicians on it. I was interested in all the different streams that fed into bluegrass: blues, various kinds of southern church music, white and black, Irish and Scottish dance music. One thing was the fiddle. That was a common thread in a lot of the musics I was interested in.”

Then there was the oud, an eleven-stringed middle eastern instrument played with the shaft of a partly trimmed eagle feather. There was an oud maker in Brooklyn who had a shop. “Any chance I had, I’d go stare in his window and I was fascinated with the instrument.” Eventually his grandfather bought him an oud and he learned to play it from listening to records and hearing Hamza El Din in concert. “I liked the tone that he got and I watched how he used his wrist and I learned to do that on the guitar, to get an oud sound out of the guitar.”

While all this exploration was going on, Jody’s interest in bluegrass began to wane. “I gave all my bluegrass records to Dave Bromberg in 1967 or ’68. I got turned off to bluegrass. Certain things started to bother me. By the late ’60s or early ’70s it was getting really formulaic. A lot of the top professionals seemed bored with their own music. That had a lot to do with it. The songs and the harmonies and all, it was kind of predictable. A lot of the musicians were understandably tired of beating their head on a wall. They wanted to make a living and they started adding more electric instruments and drums and different kinds of songs and I didn’t really care to hear it. One exception was Ralph Stanley with Roy Lee Centers. He did some outstanding stuff.”

In the late ’60s Jody moved to the San Francisco Bay area. His main mission was to study sarod at the school of Indian master Ali Akbar-Khan. Jody likes to point out that the sarod is similar to a fretless banjo, with drone strings resounding over a hide stretched over a gourd. Indian music became his main focus. ‘‘I started studying Indian music because I thought it would make me a better musician. I wanted to bring what I could learn into what I was already doing, but instead I got drawn into the music itself and wanted to get good at doing it. I saw that Indian musicians already understood what I was very tentatively working out for myself. The feeling they were transmitting through their music was something I identified with quite strongly and which moved me very deeply.”

Meanwhile, the local bluegrass scene was not satisfying. “I couldn’t connect with anyone here whose idea about bluegrass was anything like mine and I just didn’t have the easy musical friendships that I had in New York. On the other hand I did have musical friendships in other kinds of music—in old-time music and Indian music and Irish music.”

Jody’s first album, ‘‘Snake Baked A Hoecake” for Bay Records, was mostly instrumental old-time music, with overtones of Ireland, Scotland and India subtly in evidence. For much of the ’70s he performed in a duet and a variety of bands with Hank Bradley, an outstanding younger-generation old-time fiddler. The next record, “Going Up On The Mountain” (also on Bay) showcased Jody’s singing and lead guitar work on a variety of material ranging from old-time and bluegrass to contemporary folk songs and a Georgia Sea Island spiritual. The harmony chorus was a special feature of the record, featuring the voices of bass singer Larry Hanks, former Greenbriar Boy John Herald, multi-instrumentalist Fred Sokolow and a new musical associate, Kate Brislin.

Jody and Kate had met in Spokane at a folklife exhibition at the Expo ’74 World’s Fair. She was performing there with her first band, the Arkansas Shieks and Jody was with an old-time group called Houseboat Music. “Jody was already one of my favorite musicians. We did some singing and it worked from the start.” Though it was years before the two were to become involved romantically, the musical association took root from that day. On recordings and at performances, Jody would invite Kate to sing and play whenever possible.

Kate’s singing and musicianship developed along rather different lines than Jody’s, but the two share some important elements, especially an in-the-bones connection to many different styles of music. “I love music. I love so many different kinds. I’ve played bass in a traditional jazz band and sung that kind of material. My mother loved all the old New Orleans traditional jazz stuff. The Beatles . . . There’s just so much music that I love.”

Kate was born in Ohio, but spent most of her early life in the Bay Area in California before moving east for a number of years. “Music was always in my life from childhood, as far back as I can remember. We always had a piano and my dad taught me chord progressions. I remember at about age four, picking out melodies and making little two-fingered chords in the bass. I just taught myself that stuff. I heard music all the time around the house. My parents both sang and my sister and I sang doing the dishes. And I was in choirs in school and played ukulele from about age five.” [Jody chimes in: “All her sisters sing. There’s five sisters. They all have good voices.”]

“I just took it for granted. I thought everybody could sing and could play something. It wasn’t till I took a vocational preference test in college and the highest scoring thing was ‘musical performer.’ All I knew at the time was some guitar. So I looked at that and I went, ‘Musical performer? Oh my God, I have to start learning classical violin or something.’ It never occurred to me to perform music until I moved back to California in 1971. There was so much going on here. People took me in and taught me things. I wanted to learn banjo so people said, ‘Oh sure, here, I’ll show you how to play it.’ One thing led to another and before I knew it, I was in a band. The Arkansas Sheiks heard about me and said ‘Oh, a good singer who can play the banjo. We need a person in the band to do that. You’re going to do this here and learn these tunes.’ That got me going. We made a record in ’75. Then later, I started Any Old Time.” Any Old Time, which recorded albums for Bay and Arhoolie records in 1977 and 1980 respectively, was by all accounts the leading old-time music band in the area, packing them in every Saturday night for years at Paul’s Saloon, the local bluegrass hub. The band was all-female, but only by coincidence. “It was who was available at the time and who was free. And we were friends and we’d been doing little pickup gigs here and there. A local Irish pub needed a band on Tuesday nights, so we said, ‘OK, we’re a band.’ “We didn’t start out intending it to be all women, but we intentionally kept it that way after a while because it worked out real well. We were really good friends and we got along well and I think that translated on stage. I think people could tell that we liked each other and there was a lot of joy when we played together. Offstage we could talk about boyfriends and our lives.”

As the group’s reputation grew, so did touring opportunities and Kate soon found herself a road musician and even something of a banjo celebrity, featured in a Banjo Newsletter cover story in 1978. In that article she cited a wide variety of influences, from older players like Tommy Jarrell, Sidna Myers and Matokie Slaughter, to younger ones including Hank Bradley and Walt Koken. As a band player, her emphasis was on driving rhythm and crisp attack, though the wide range of music she now plays calls for an expanded variety of shadings.

Kate’s next musical association was with the Blue Flame Stringband, an old-time-based but highly eclectic quartet which made a well-received album for Flying Fish in 1983. Their music included elements of Cajun, jug band, rockabilly and bluegrass, with Kate contributing on banjo, guitar and even occasional kazoo! By 1984, however, when Blue Flame disbanded, Kate was ready to be off the road for a while. Musical opportunities continued, including singing on albums by Laurie Lewis and others. Gradually, she and Jody began to work together locally and the possibilities once again grew.

The appeal of a performing duet was strong. ‘‘I really like a sense of connection with the audience that seems to be more possible as a duet than it was before. There’s an intimacy and I’ve always enjoyed the thrill of singing something for an audience and having them really seem to like it the way I like it, to appreciate it.

‘‘I’ve always been in bands until now. A duet is more demanding. It’s been challenging for me. It’s forced me to learn how to do things, like carry half the act, do half the talking and get better at my instrumentation. As far as singing goes, your voice becomes an important part of making a big sound. When you’re not playing with five people, something’s got to take up that space. I used to think that the ultimate singing experience would be a quartet and I still really enjoy that. But it’s come to be that there are more and more songs where I don’t really hear anybody else, just one other person. A duet gives you the freedom to just hit the intervals you want to hear and not hear every single interval filled out.” Jody adds, ‘‘Kate’s a vocal chameleon. She has a very supple voice and there’s a lot of different sounds she can make, too. I’ve heard Kate sing with numerous singers, male and female. She can find something in her voice to blend with anybody. That’s why she’s so great to sing with.”

Kate also relishes “how comfortable it is to travel together. Having a home away from home, having somebody there who really knows you and is real supportive, who you have a good time with. Traveling brings out the playful side in both of us, so we seem to always have a great time together.”

Jody: “Audiences tell us that they feel something between us. There’s kind of a charm or a spell. Making a strong mood of some sort is one of the main features of our music. But we don’t exactly set out to do that. People have commented on this thing, but it’s sort of a byproduct. It’s a nice one. We’re just making the music that sounds good to us.”

Jody’s philosophy of music could fill a book, but here are some of the essentials of his outlook:

“I listen to music as much as I can, hours a day usually. I play every day, I practice it. I’m always learning new songs and tunes. I’m fascinated with the fiddle. I like fiddle music of all sorts.

“Two things I like to do: One is take a song or tune and really polish it, play it thousands of times and turn it into a gem and make an arrangement and make it part of me.

“And the other thing that I like to do is to take a tune or song and completely destroy it (laughs), take it into pieces and rearrange it and do it like that and improvise and do something different on the spot. So these different tendencies are both at play when I perform. On the one hand are songs I’ve sung for so long—and there’s brand new songs, too. The ones I’ve done so long, there’s something that’s really familiar, but each time I’ll do something different.

“One thing I’ve always enjoyed with all my musical partners is I don’t know what they’re going to do exactly and they surely don’t know what I’m going to do. Kate’s like that. She sings some real unexpected notes sometimes or she’ll just change the timbre of her voice. It keeps me on my toes.

“I think the audience enjoys it when they are privy to the heat of creation, when something’s being made right then. There’s a certain energy when improvisation happens, when you’re making something brand new, for the first time, right there. It may not be as polished, but it’s extremely exciting and interesting and enjoyable to hear that. So I guess I’ve got these two parts. They’re balancing each other, hopefully.

“One of the things that’s affected my whole philosophy of music has been through my contact with Indian musicians. Music is not considered to be only one thing. Music is prayer and music is entertainment and music is exhibiting your chops and music is competition and music is cooperation and music is rhythm and melody and of course in our case it’s harmony as well—and not any one of those things. You know, there’s this conflict you hear about: ‘Do you want to express the music or do you want to express yourself?’ Well, there’s no conflict. There’s room for all of it … at the same moment, in the same two minutes anyway.”

Jody’s listening library includes generous helpings of so many different kinds of music, it’s hard to imagine one person being familiar with it all. But all the musicians and styles from around the world are like old friends to him and a visitor never knows what new instrument or sound will emerge when Jody pulls out one of his vast array of cassettes or albums and coaches a listener to understand and appreciate it. In addition to all the varieties already mentioned, he listens avidly to rembetika music (“Greek blues,” Jody explains), Turkish classical music, Portuguese and Brazilian music, Irish and Scottish, Cape Breton fiddle music . . .

“Any musician that’s well-known for doing one thing, if you look a little deeper, you’ll find that they’re interested in a lot of different kinds of music. Most musicians are, including traditional musicians.” But sometimes Jody is worried about people knowing the breadth of his musical interest. Why?

“So they won’t think I’m a flake—just touching the surface, or dabbling. I don’t consider myself a dabbler. I do listen to a lot of musics I’ve never attempted to play. I don’t have that much time (laughs) to play everything!”

The variety of Jody’s musical experience is anything but a liability. Rather, it weaves together like an intricate tapestry and yields technical and artistic aspects that enrich all the music he plays. Don’t look for an Indian or Irish lick in a bluegrass tune where it doesn’t fit. What you’re more likely to find is an unusually fresh approach which somehow belongs because of his deep understanding of the nature of all traditional music.

“One group that we recorded in the Bahamas . . . The way that they sing is the four of them would all hold hands and sing the song through two or three times humming. Without any words. Then they would break handclasps and move their hands as they sang. I don’t know if the description means a thing but it made an enormous impression, the way the music slowly, slowly, slowly unfolded. Very powerful. The humming, it just came from out of nowhere. (Begins to hum gently:) ‘Will you be there, my dear brother/At that great coronation?/Will you be there/Early in the morning?’ Then this guy comes in … (in a powerful tenor): ‘When they crowned him Lord of all.’

“Studying my own music, looking back at the various kinds of music I’d make, I’d see that almost everything I do is really some kind of bluegrass. My timing is bluegrass and the type of harmony I like and the sounds I make with my voice are bluegrass. So I’m coming back into it. I’m realizing how much I enjoy doing it and getting together with people I can sing and play with.”

Being in Owensboro for the entire week of the IBMA Trade Show and Fan Fest encouraged Jody and Kate that the bluegrass scene has a place for their music. Jody: “Because of things that had happened to me in the past, I expected to meet with more narrowmindedness: ‘If it doesn’t adhere to some particular formula, not only is it not bluegrass, it’s not music.’ I didn’t find that to be true. I found that not only were they receptive to our music, but I could tell by various conversations and things that I heard that the tastes were very very wide. Most people were open to all sorts of things.”

Does this mean Jody and Kate are looking forward to big changes in bluegrass music? Not at all. Jody again: “I don’t think developing it means necessarily having jazz harmonies or adding more electric instruments, or going rock. I think within the sounds we hear as bluegrass it hasn’t all been explored. There’s more that can be done. Basically to me it’s country music. Maybe that’s what it comes down to and maybe it’s ironic coming from someone that grew up in the city, but it’s the country things about bluegrass music that I like best. Maybe that’s what it comes down to, really.”