Home > Articles > The Archives > Jimmy Arnold—Back Again and Ridin’ High

Jimmy Arnold—Back Again and Ridin’ High

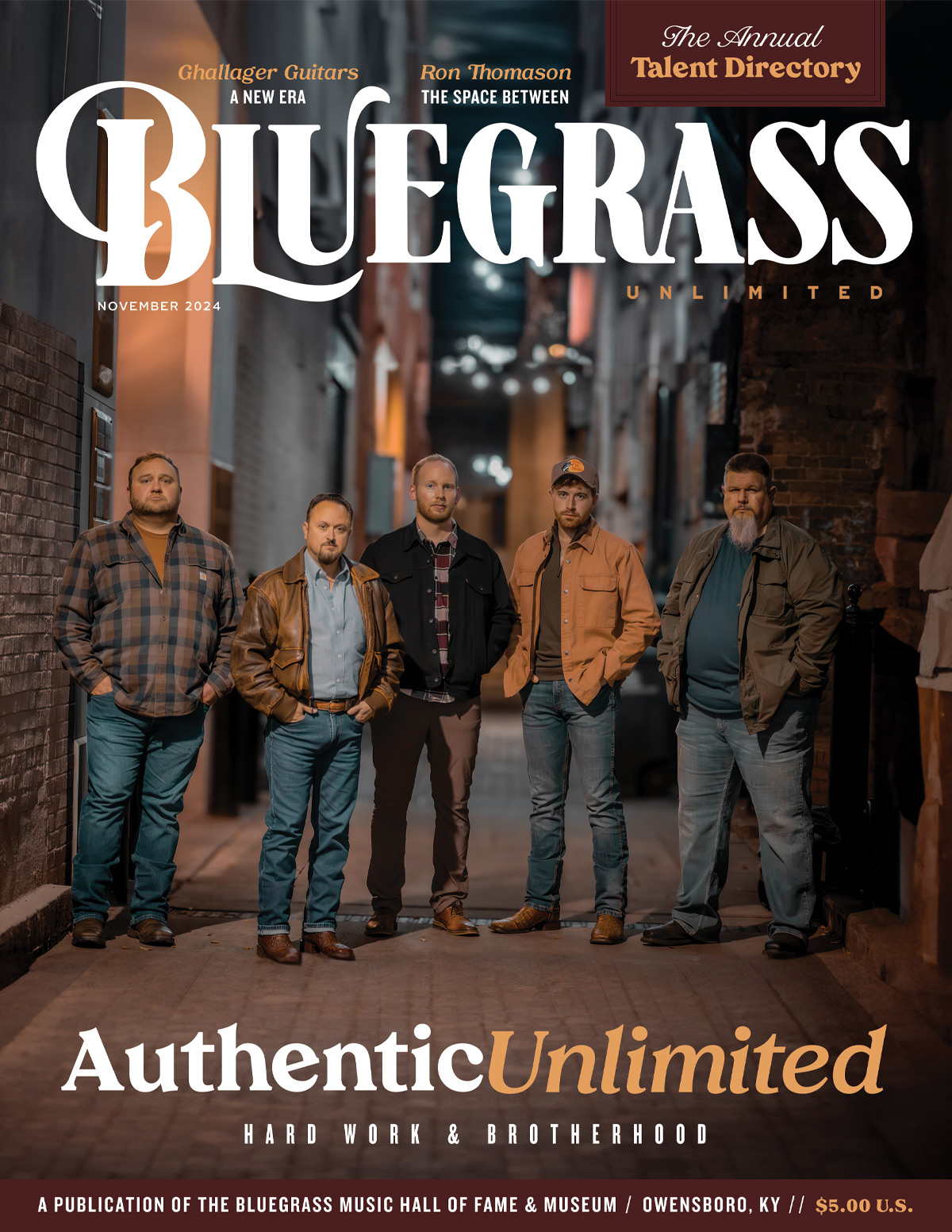

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1983, Volume 17, Number 11

Jimmy Arnold popped in and out of the bluegrass scene in the seventies. During that time, the Virginia native managed to record one banjo and one guitar album for Rebel. Jimmy also put in a few years playing mainly banjo with Joe Greene, Cliff Waldron, Charlie Moore, Country Store and the New Tradition. Sometimes his absences from the scene were due to his battles with alcoholism and drugs. At other times, Jimmy was off playing country-western music in Las Vegas and Houston. After a few years without a new solo album or an appearance in a touring bluegrass band, he resurfaced, this time as a fiddler on two recent releases, Wayne Yates’ “Relivin’ Old Habits” and Mike Auldridge’s “Eight String Swing.” “Rainbow Ride,” his second banjo album for Rebel followed and has been very well received.

Late in 1981, Jimmy moved back to Virginia after a stay of about two years in Texas. “I knew that for my style of music, I would have to go back, if I was really that interested in making another mark in music that it would have to be around the Washington D.C. area, because that’s where my audience would be. And I’ve been out of it long enough to where I figured it would be a good time to go back and make a mark here, and if I made strong enough a mark, I could go to other places and be accepted.”

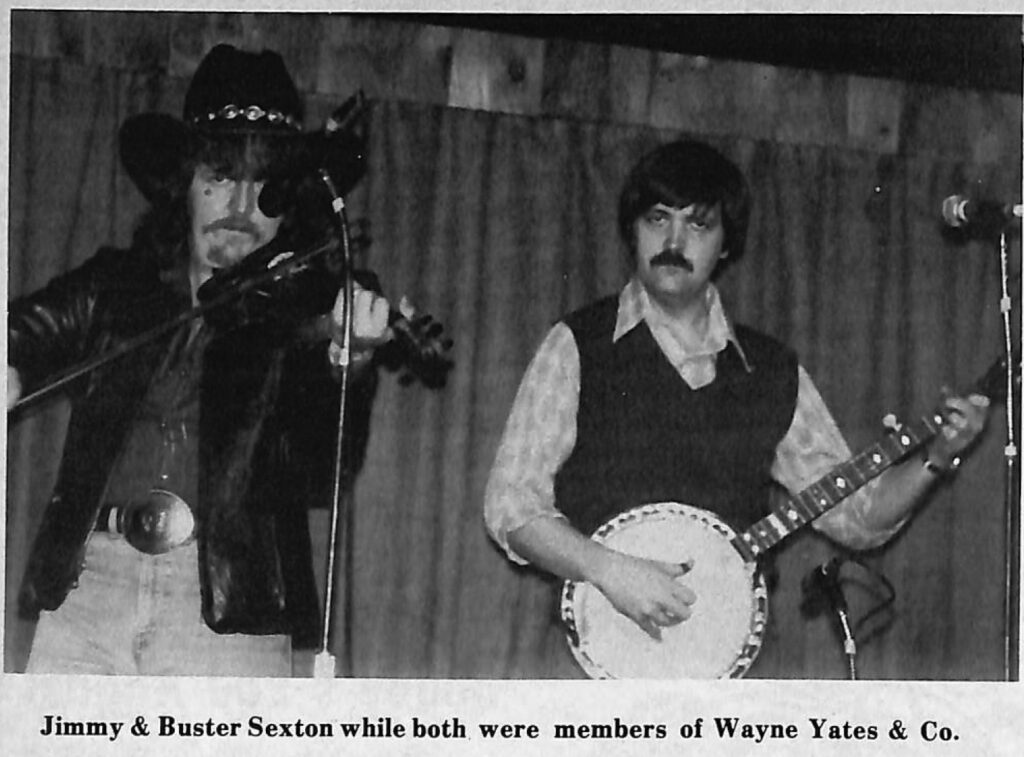

Jimmy happened to be home for Christmas and able to sit in when old friend Wayne Yates was recording his Outlet album. When he returned to Virginia a number of months later, he began to do some work with Wayne Yates and to teach at Pickers Supply in Fredericksburg. But, Jimmy stated, “I got restless and it wasn’t enough income. So I started doing a single act on the side. And became a singer of some degree.”

If you check over any of Jimmy’s solo albums, one thing you notice is that no human voice emanates from the collection of vinyl. Jimmy Arnold a singer? Banjoist, guitarist, fiddler, we know all about that. In the past, Jimmy hadn’t sung more than harmony parts “and had to be forced into that,” he shuddered. “I hated singing. I figured, being almost thirty years old, if I’m really going to be what I want to be and make any money whatsoever, I’ve got to learn how to front a band and sing. So, I figured, here’s the fine time to do it, in a lounge, five nights a week, where there’s not that many people, and I can’t hurt a lot of ears.” Not only has Jimmy been singing, he’s been writing songs, close to one hundred of them in the past year.

Jimmy was born in Galax and raised in Fries, a small town in southwestern Virginia. His parents did not play, but they were aware of and supportive of bluegrass and country music. Jimmy started off with guitar at the age of ten and really began working at it a year later. However, what he called his “first sincere attempt” at serious playing was on the banjo.

“I was more intrigued by the banjo than anything else because back then Reno and Smiley had a TV show called ‘Top of the Morning’ in Roanoke, Virginia. I was real intrigued by Reno’s left hand and just by the sound of the instrument itself. It was real haunting to me, like a real mountain resonance to it… that really caught my ear more than anything else.” Even the shape of the banjo fascinated him. “It was just a unique thing to me.” When Jimmy decided he wanted a banjo, his father opposed the idea, feeling that Jimmy should stick to one instrument; the $15.95 guitar ordered from the Sears catalog. Jimmy was determined, though. He had a pony which he traded for a cow. He then sold the cow and bought a banjo.

Jimmy had been playing less than a year when he joined his first band. There was a young fiddler in Galax named Jimmy Edmonds, he recalled. “His dad was putting a band together for him. The guitar player was Wesley Golding.” (Wesley went on to play with Boone Creek and the Shenandoah Cutups, and Edmonds recorded an album for Kanawha with the Carolina Buddies.) “We met at a place called the Auction House that night over in Hillsville. I started playing with them, and that’s the same night I met Butch Robins. Butch told me that very night that I had the best right hand he’d ever heard, and he would really like to help me.”

Jimmy never had any formal lessons. “I had always tried to play everything real smooth, and there was a guy named Elmo Reynolds in my hometown that showed me a whole lot as far as rolls and a couple of tunes. And then Butch got hold of me and turned me on to the Reno style. Butch Robins really helped me more on the banjo than anybody as far as technical knowledge. Butch is still one of my favorite pickers.” Jimmy and Wes soon branched off into their own band, the Twin County Partners, and had their own radio show. The early version of the band had Jimmy’s cousin Tommy Arnold on mandolin and Wes’ father Wayne on bass. “It was a hot little band,” Jimmy said, thinking back. “We did a single record on the Stark label.” He and Wes played together for about three years. They eventually made an album with Parley Gray on mandolin and Joe Edd King on fiddle. At that time the band was called the Virginia Cutups.

The band had already performed with Flatt and Scruggs and Reno and Smiley and was well known. The Virginia Cutups had been playing bluegrass festivals, had done the Ernest Tubb Record Shop show, played other jobs in Nashville and some television shows and “had been offered several deals as kids” to work full-time. Jimmy’s parents made it mandatory that he finish high school, so the stresses of life on the road were put off for a while.

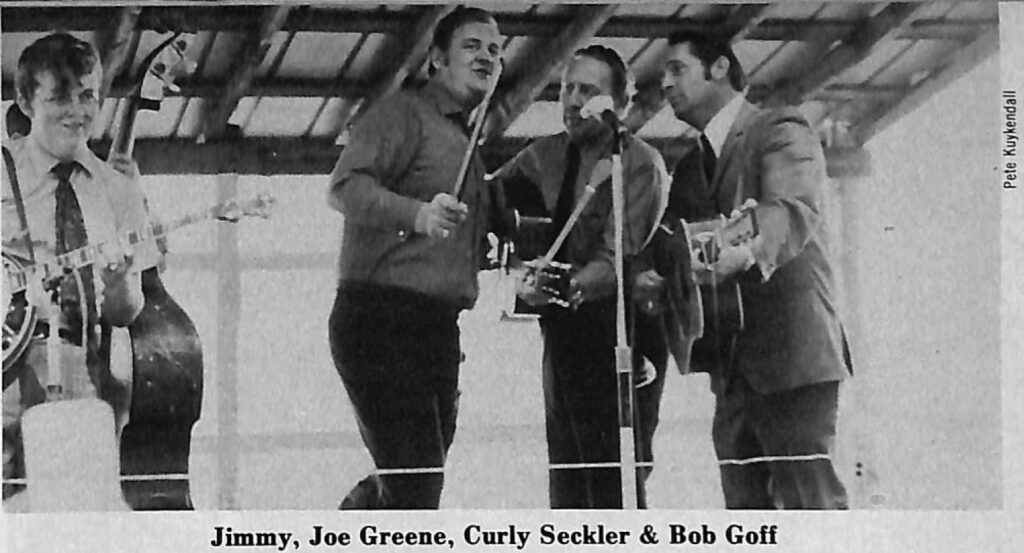

Following his graduation from high school, Jimmy played with fiddler Joe Greene for a few months. “I probably learned more about playing fiddle tunes on the banjo and about drive on the banjo from Joe Greene than anybody in the business.” Jimmy left Joe Greene’s band for home after a relatively short stay, a move he somewhat regrets now.

Around 1971, Jimmy joined Cliff Waldron’s band, the New Shades of Grass, a group based in the Washington, D.C. area. “I had met Cliff while I was on tour with Joe up in New York. We used Cliff to go up and do a show with us. Cliff heard my banjo playing and about that time, Ben Eldridge was interested in quitting. When I came home, I had been working weekends with Wesley and Wayne Golding again. But we played a festival. I ran into Cliff again. And he gave me his records and stuff. I had maybe a week to learn them all. I went home and actually learned them all note for note and came and played with them at Camp Springs [North Carolina] and it just blew their minds away.” Jimmy left Cliff Waldron after cutting three albums with the band.

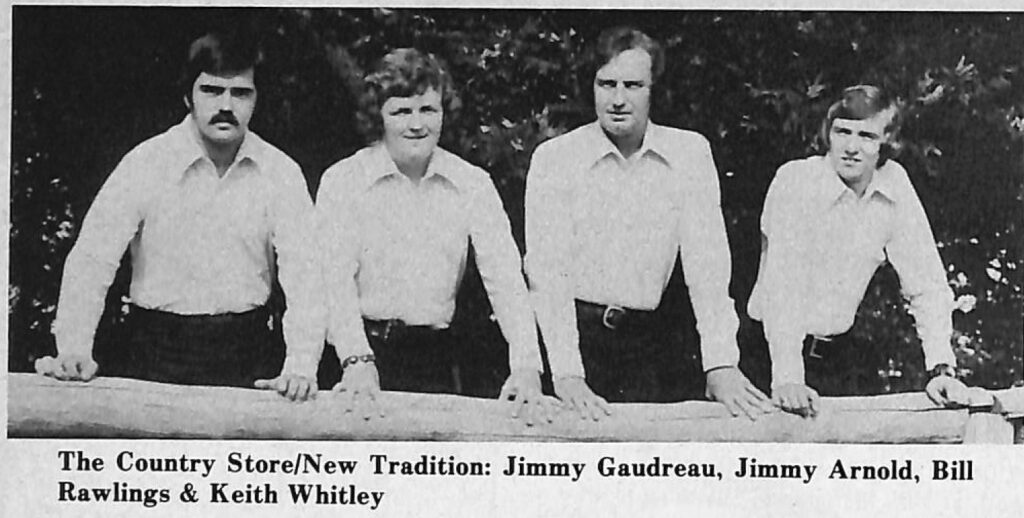

The young banjoist then moved on to play with Charlie Moore and record an album with him. He then performed with a group called variously the New Tradition and Country Store. When the group started as the New Tradition, it was to include Keith Whitley on guitar, Jimmy Gaudreau on mandolin, Carl Jackson on banjo and Bill Rawlings on bass. Before the band really got going, Jackson left to play with Glen Campbell, and Jimmy replaced him. Later Pat Cloud, the jazzy California banjoist, would replace Jimmy, and Jimmy would replace Pat. “All this time I was having bout after bout with alcoholism and drugs,” Jimmy explained. “That was more or less the reason I was in and out of the scene so much.” Jimmy recorded one album with Whitley and Gaudreau in June 1973 live at the Shamrock Bar in the Georgetown section of Washington, D.C. The album eventually appeared on the Japanese Red Clay label.

Jimmy had played some fiddle all along and, in 1977 and 1978, he ended up playing fiddle with the Judy Lynn country show in Las Vegas. Bobby Hicks, the former Blue Grass Boy, had just left the fiddler’s post with the show. He heard Jimmy’s playing and helped him to obtain the open job. “At that time, I wasn’t even what I would consider a fiddle player,” Jimmy opined. “Bobby said it would be no problem, that I would just be playing parts, and as good of a banjo player as I was, I’d be an instant success, which turned out to be true.” After playing with Judy Lynn, Jimmy moved to North Carolina. From there he worked odd jobs and played in a house band at Partners II in Centreville, Virginia, but was not involved in music on a big scale.

Jimmy’s next move was to Texas. He had always been interested in the music of Bob Wills, the late king of western swing, and fiddler Johnny Gimble. According to Jimmy, Gimble “is an amazing fiddle player. He’s just got such a tone and everything. I wanted to go meet Gimble and learn more about Texas music. At that time, my dad gave me the timber rights to his farm, so I went up and sold some of the timber and got some money in my pocket and went to Texas.” He met Gimble and did some playing with Gimble’s mentor, Cliff Bruner, another western swing great. Through other fiddlers, he found a job in Houston with a house band. “At that time, the Urban Cowboy had just come out. If you were a fiddle player, you could do no wrong. They thought you hung the moon.” With his range and the variety of instruments he could play, Jimmy “fit right into the scene. I got me a nice salary and a lot of studio work. And was real happy down there.” Jimmy spent 1980 and part of 1981 in Houston, but got homesick for Virginia and decided to move back.

By his own recollection, Jimmy’s solo recording career began as “just a spur of the minute thing.” After working with Charlie Moore and then the New Tradition, he had gotten married and gone into semi-retirement from music. He was working at a service station in North Carolina and went to a music festival there. Jimmy saw Dick Freeland, then owner of Rebel Records, and walked up to him. “‘Man,’ I said, ‘I’ve always wanted to make a banjo album. I’m just kind of scared to ask.’ He said, ‘Hey, any time you want to,’ and I said, ‘I’ll pay the tab.’”

Jimmy went back home, chose twelve tunes and rehearsed them for about a week. At the time, he hadn’t been playing much at all. “I got ’em in my head like I wanted them and went up to the studio and cut the entire album in less than eight hours. It became pretty much a landmark for me. At the time, I wasn’t even thinking at all about making any dents or anything. I never do anyway. I just play what’s in my heart and on my mind, and it seems to be accepted pretty well.”

The album, recorded May 16, 1974, was released under the title “Strictly Arnold.” Mike Auldridge played Dobro and Cliff Waldron guitar. Japanese players Akira Otsuka and Gakusei Ryo contributed on mandolin and fiddle, and Ed Ferris played bass. The numbers chosen showed the range of Jimmy’s influences and interests. Included were a number of tunes that he named for other people, a couple of swingy tunes and a few reworkings of classic bluegrass breakdowns and fiddle tunes.

The tune called “Tommy Jarrell,” actually the fiddle tune “Forked Deer,” was Jimmy’s tribute to the great Mount Airy, North Carolina old-time fiddler and banjoist. Jarrell has a number of albums on the County and Mountain labels. “I met Tommy when I was just a kid, and Tommy kind of took me under his wing. Every so often I’d go down on a Sunday afternoon and sit with Tommy and play bluegrass banjo and learn those tunes from him. He would play fiddle for me to learn from and sing. We became the best of friends. Through that, that’s why I put that on the album, due to him.”

“Boarman’s Way” was another tribute, this one to Andy Boarman, whose banjo and autoharp playing has been documented on an album on the June Appal label. “I met Andy also when I was a kid, and Andy kind of took me under his wing and showed me things that I didn’t even know existed on a banjo.” The tune itself is “Home Sweet Home,” played classical style, solo, as Boarman plays it.

“Wayburn’s Fiddle”? “That’s Wayburn Johnson. He was another fiddler in Mount Airy, who was just a high energy, tremendous fiddle player. Wayburn played ‘Cincinnati Rag’ better than anybody that I knew of. So that’s what the tune really is, and I named it after him … any renaming I’ll do of a tune, except for one, is just in memory of a person.”

“Strictly Arnold” is actually the Earl Scruggs tune “Shuckin’ the Corn.” “People used to ask me to play ‘Shuckin’ the Corn.’ There’s five or six tunes with that chord progression. I figured if I was just using the chords and wasn’t using anybody’s licks but mine, why name it something else? If I did, I would almost be making fun of somebody else’s song.”

A couple of numbers, like “Doing My Thang,” “Ruby’s Song” and “Charmine” had a swing feel. “Doing My Thang’,” said Jimmy was “an old progression,” like that in “Bring It On Down To My House Honey.” “Charmaine” was recorded by swing jazz bands back in the thirties, including the Jimmie Lunceford Band. Jimmy had never heard those versions. He got the tune from Joe Greene who liked to transform different kinds of songs into bluegrass. “Back then, I actually didn’t know where they came from. The only thing I knew was I liked the tunes, and I liked the more chordy stuff and wasn’t familiar with jazz, as a name for music until later years, when I really got into the stuff, like some of the old standards, ‘Misty,’ ‘How High the Moon.’ ”

Jimmy’s second album, entitled “Jimmy Arnold Guitar,” appeared in 1977. He had dabbled in guitar for quite some time. “I was doing a lot of stuff on classical guitar, almost Jerry Reed-like. And I wrote a lot of tunes, so I took ’em up and let Dick Freeland hear ’em, and he wanted to put a record out.” The sidemen included Mike Auldridge and Steve Wilson on Dobro, Ricky Skaggs on fiddle, Akira Otsuka on mandolin and Johnny Castle on bass. Some of the tunes were nearly classical sounding, one had a Latin feel, others were in the vein of “a real funky, progressive, finger-style classical guitar.” Jimmy now plays an Ovation, but on the album he used a Yamaha classical, “the cheapest one they had. It was just one of those things. You pick it up and it sounds good. A freak accident.”

Jimmy is noted for his playing of hornpipes and fiddle tunes. “A hornpipe is real enjoyable to play, because of the melodic thing. I’ve tried to combine a powerful right hand with the other things. I do some single string stuff that I got from Reno and some of the melodic stuff I got from [Bill] Keith and [Bobby] Thompson. And run that all together to where I can still keep the power in my hand. And drive it like an old-time fiddler would. It requires a little bit more involved work with the fiddle tune, but you come out with a little bit better product because it is every bit as punchy. If the banjo player put the same kind of attack on it that the fiddler did, it’s a little more effective.”

Jimmy’s latest album, “Rainbow Ride,” was recorded with help from Mike Auldridge on Dobro, Wayne Yates on guitar, Mark Newton on mandolin and Ed Wilson on bass and was released in 1982. The selection of tunes had some similarity to those on “Strictly Arnold.” “Little Rock Getaway” came from the swing-jazz fields. A solo version of “The Entertainer/Maple Leaf Rag” was in tribute to ragtime composer Scott Joplin. The “Crazy Banjo Rag” was a fiddle tune, Howdy Forrester’s “Wild Fiddler’s Rag.” “Hub’s Rag” was an original composition in honor of Hub Nitchie, publisher of Banjo Newsletter, who “helped me a whole lot as far as getting my name out and giving me good compliments as a banjo player.” “Rainbow Ride” showed the influence of steel guitar players on Jimmy’s music. “Medusa,” a number featuring double-tracked banjos, was co-authored with Butch Robins. On “Mountain Man,” Jimmy frailed the banjo and showed off a little more of his own fiddle work, along with the lead guitar and harmonica he contributed to the album.

Two tunes were extremely hard driving numbers. Jimmy wrote “Ridin’ High” while sitting around with Wayne Yates in his basement. “It was one of those things where it seemed like the more parts I added to it, the better it came out. It just left room for a lot of creative thinking.” “Cattle in the Cane,” a fiddle tune, came from a Joe Greene version. “On that tune, especially on the second half, you get a dynamite chance to really drive there, when you hammer it on the second and first string, when you come into the A major part.”

Jimmy explained how he goes about deciding what he will do with a tune. “I try to take a tune and break it down and play it as understandably as possible and allow places for coming in and out of things, doing things that are real tasteful, but not real tacky like completely destroying a song. I like putting maybe one lick in a tune that is just a real bizarre, pretty lick that people can identify with. They like the basic drive and playing of the song, the arrangement of it, but here comes this lick out of nowhere and disappears.”

To Jimmy, the master of bluegrass banjo is clearly Earl Scruggs. He considers Scruggs to be his main influence for tone, power and clarity. “When you learn all of what you think is hard stuff and then go back and try to play one of his tunes, you find out what the hard stuff really is. It’s his stuff. To play with that much power and volume, you’ve really got to be on top of things.”

Jimmy played what he called a “throwed together” Mastertone on his first album and a Lane banjo on “Rainbow Ride.” He thinks that “a lot of people dwell too much on the mechanics of a banjo.” According to Jimmy, “They get carried away with it, trying to make it sound a certain way. If you practice drive with your right hand, and squeeze a rubber ball, build up your strength in your hands, you can reduce the need for a great banjo. For example, a guy says, ‘Man, I can never get my banjo to sound like your banjo,’ but I can take it and make it sound like mine. It’s about a 50-50 deal. If a good banjo player’s got a bad banjo, you can give him a good one and really bring him out. The first time I ever played on a really good one, people came around from everywhere and said, ‘Who’s this kid?’ I’d been playing on something they couldn’t hear, and all of a sudden it just blared out.”

Jimmy now plays a Barcus-Berry five-string fiddle. “I think it’s the best fiddle I’ve ever had. It’s got a real droning sound. It gives you that low end. It’s a combination violin and viola. I’ve had it three or four years. Bobby Hicks turned me on to that kind of thing.” For jazz and swing playing, Jimmy loves Johnny Gimble, Joe Venuti, for his power, and Stephane Grappelli, for his technical genius.

Jimmy’s tattoos may be something new to those who knew him from his past bluegrass exploits. He got into tattoos when he was in Houston. “I thought it was beautiful. I thought it was the most personal form of art that a person can have. The tattoo people look at it as a symbol of power. If a man can stand that much pain, he can pretty much deal with what life has to offer him and not get too excited about it.” Jimmy tried to use Tattoo Music as the name for his music publishing, but it had been used before. He is changing the name to Cathead Music. “The cathead is a real big tattoo symbol,” he explained, “a symbol of power like the tiger’s eye.”

Jimmy clearly has been on a “Rainbow Ride.” He has explored a number of forms of music, played a variety of instruments and experienced successes and tragedies. The powers of self-control and self-direction are extremely important in developing any career. A person has to know what he or she wants to do, figure out how to do it and then go ahead and do it. Jimmy Arnold knows that he has to sing, wants to make an album on which he will sing and that he wants to make another mark on the music scene. Let’s hope he keeps on “Ridin’ High,” this time without any teardrops.