Home > Articles > The Archives > Jim Mills

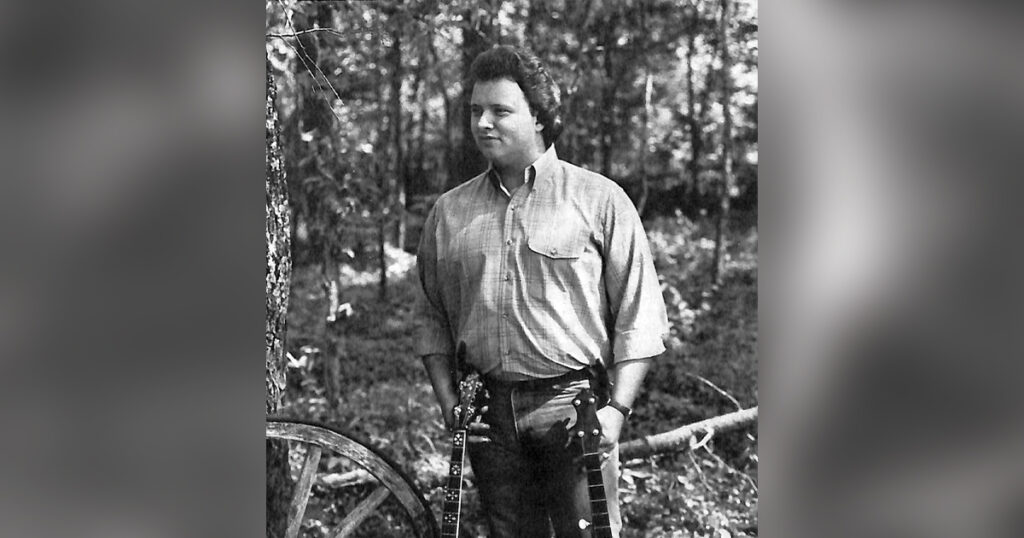

Jim Mills

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1990, Volume 24, Number 10

It was a weekday night in late September of 1988, that Doyle Lawson called. Jim Mills remembers it well. “He said, ‘Would you be interested in playing banjo for me?’ I said, ‘I sure would.’ Jim thought to himself: This is it!”

Ten days after joining the critically-acclaimed band, Jim Mills found himself far, far away from his familiar North Carolina surroundings, introducing bluegrass to thousands of people who had never heard the ring of a five-string banjo, a G-run on a guitar, or the tremolo of a mandolin. Six weeks touring ten South American countries served as Jim Mills’ initiation as Quicksilver’s new banjo player.

Sipping coffee, sitting at the kitchen table with his father back in their Durham County, North Carolina, home, the stocky 22 year-old with wavy, reddish-brown hair smiles as he recalls the experience. “Thing about it was they’d never seen a banjo before. They’d seen mandolins and guitars and basses. But they’d never seen a banjo before. A lot of them came up to me just to look at it and count the strings.” Serving as an ambassador of bluegrass for the American embassies, Jim was impressed with the audiences they attracted. “We had crowds every night,” he recalls. “At one place we played a theater that was supposed to hold 600 people . . . [it] had about 900 people in it. They were standing in the aisles and beating the doors down to get in.”

In his overly-modest way, Jim talks about the phone call from Doyle Lawson in 1988, as if it were a happy accident or undeserved blessing, “I’ve been awful lucky,” he says. But in fact, his new job as banjo player in one of the country’s most popular and accomplished bluegrass bands is a not-so-surprising result of years of dedication to the banjo and his prodigious natural ability.

Although more than competent at handling a mandolin, fiddle or upright bass, this North Carolinian’s preference for the banjo extends a family tradition. Both Jim’s father, Jim Mills, Senior, raised near Keysville, Virginia, and Jim’s grandfather from the mountains of North Carolina, played the instrument in a two-finger style. Jim, Senior, recalls that his father would play at dances with a guitar player and a fiddler and that his favorite tunes were “Cripple Creek” and “Rabbit In A Log.”

“What they’d do, they’d go to a dance and they wouldn’t play but those two songs for an hour and a half a piece … it was something to pat your foot to, that’s about all it was, just a whole lot of noise with some time to it.” Jim, Senior’s, enthusiasm for the banjo got a big boost when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs took their tent show to his hometown of Keysville, Virginia, in 1952 or 1953. “That was the biggest thing that ever hit town,” recalls Jim, Senior, who was sixteen or seventeen at the time. “It was the last show that Jody Rainwater ever played with them. He went on from there to Crewe, Virginia, and became a radio announcer.” He remembers Lester Flatt handing out bags of Martha White flour to the youngest and the oldest married couples in the audience and the banjo wizardry of Earl Scruggs which set the small town on fire. Jim, Senior, was working as a short-order cook in town and had the pleasure of providing the hungry Foggy Mountain Boys with hamburgers, hot dogs and french fries.

Jim, Junior, began learning the two-finger technique of his father at about age ten on a banjo his father acquired one Sunday morning in downtown, Raleigh, North Carolina. “He was just riding through town and saw a black fella sitting on his porch just thumpin’ on it … an old man. Daddy pulled up in the drive, walked up there and asked him whether he wanted to get rid of the banjo. The old man said ‘I wasn’t planning on getting rid of it, but I sure would like to have a fifth of liquor.’ It was Sunday morning and you couldn’t buy any. Daddy said ‘Well, I’ll sure go get you one.’ He knew where he could get one on Sunday, brought it back and traded him—an even swap.” Jim still owns the open back banjo with a calf skin head and walnut neck which has since been estimated to be pre-civil war in age and which, according to Jim, “might be worth a little money.”

Jim’s next instrument was a Supro banjo. I bought it at a flea market at a horse show in Roanoke, Virginia. Boy that was nice; it was like a Gibson to me then. Played it till I was about fifteen years old.” Without the benefit of many bluegrass banjoists nearby to learn from, the young Jim Mills learned mainly by listening over and over again to the recordings of Earl Scruggs. “About the only records I had, in fact were Flatt & Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers…Earl Scruggs was my main influence he still is today.” Jim says that he is still learning new tricks from old recordings of Earl’s live performances. He also credits J.D. Crowe, Terry Baucom, Sonny Osborne and Raymond Fairchild as major influences in the development of his banjo skills.

Today Jim Mills, who considers himself a banjo player of the traditional style—“I’ve never been what you call a ‘melodic’ banjo player”— plays a recently acquired 1930s vintage Gibson Mastertone with what he believes is a TB-3 pot.

It was apparent to his family from an early age what career Jim wanted to pursue and that he had the natural ability. “I thought back when he was picking with two fingers that he’d be just a little better than the average picker,” Jim’s father says, “He had that timing.” Jim admits that playing the banjo is about all he ever wanted to do. “Every little boy has a dream about what he wants to be when he grows up—a policeman or fireman or something like that—I always wanted to be a banjo picker, that’s what I dreamed about.”

Having only his records at home to learn from, informal jam sessions and parking lot picking at bluegrass festivals were all the more important in Jim’s progress on the banjo. His father fondly recalls the first time he took Jim to his first bluegrass festival at about age fourteen. “We got there and all those great big speakers were going, those banjos and fiddles were pickin’ … his eyes lit up like a kid’s at Christmas. He had his own banjo with him, he was pickin’ a little bit then. He picked with everybody on the showgrounds, that’s a fact. All day and all night he picked. The next morning when the sun came up he finally got a little sleep. When he woke up all ten fingers had sores on ’em. I put a couple of Band-Aids on each finger and oh boy, he was sad the rest of the day. He couldn’t pick, he just walked around and listened . . . heartbroken.”

One such opportunity that particularly stands out in his mind some seven years later is when Terry Baucom, then banjo player for Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver, taught him to play “Pike County Breakdown” at a festival in North Carolina. As Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver were about to go on stage, young Jim, finding his friend’s car locked, was unable to put his banjo away after a session of parking lot picking. “So I walked on down to the stage with my banjo around my neck,” he recalls. “Doyle wasn’t on stage yet, so I just walked on down behind the stage. They were back there practicing before they went on. Nobody said anything to me, I just went right up there. Terry Baucom was tuning his banjo and straightening his necktie, Doyle was tuning … Jimmie Haley was talking to somebody over by the steps and Randy Graham was standing on the steps. I walked over to Terry and said, ‘You wouldn’t help me learn a tune, would ya? I’ve been trying to learn the ‘Pike County Breakdown’ for a week.’ He said; ‘sure!’ He turned around, had his banjo in tune and he tore down on that thing, I mean he burned it up! He played about one break to it when Doyle had got done tuning and started chopping on it and then Jimmie Haley came down the steps and joined in on it—all three of them playing the ‘Pike County Breakdown.’ About that time the band up on stage got done and the announcer said ‘Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver!’ They went on up the steps picking the Pike County Breakdown’!” Little did Doyle Lawson or Terry Baucom know they had tutored a future member of the band in that short, impromptu jam session.

After finishing high school, Jim played on and off with different local musicians for a while before joining Summer Wages of Mt. Airy, North Carolina, in which he played for about two and a half years. Jim, Senior, says, “I made up my mind there that the bug had bitten him and bitten him good. He was going to be banjo picker.” While on the road with Summer Wages Jim frequently crossed paths with Doyle Lawson and the two became well acquainted. Doyle Lawson knew exactly the caliber of Jim’s banjo playing and character when he asked Jim to join the band in September 1988. But as any fan of the band knows, instrumental virtuosity is only a part what’s required as a member of Quicksilver, a band that has made its reputation in good part on the strength of its vocal arrangements, particularly on a cappella gospel harmonies. Improbable as it seems, Jim Mills had never sung on a regular basis with a band when he got the phone call from Doyle.

“The biggest shock of my life was the first show I went to see him play with Doyle, they had taught him to sing! I didn’t know he could sing a note,” Jim’s father says. Jim gives Doyle, Russell Moore (guitar) and Ray Deaton (bass) the credit for teaching him how to sing the baritone part in the band. “They taught me to sing from my diaphragm instead of my throat. I didn’t know I had a good baritone voice, but they tell me I do … everybody seems to be real happy with the vocals. I’m real happy with it and I like singing a lot. It’s a lot of fun singing when you got a bunch of guys like that to sing with.”

Learning to sing was only one adjustment Jim Mills had to make as the newest addition to Quicksilver. The young banjo player had to learn quickly all of the band’s old material. “Doyle handed me ten albums,” recalls Jim, “and said ‘we know our part.’ … that’s one hundred and fifteen songs.” Jim spent hour after hour in a room with his record player and his banjo until he could faultlessly reproduce the banjo work of his predecessors, knowing on which songs it was his job to provide the kickoff and where in songs he was to take a lead. “[Doyle] likes the stuff the way it is on the record, basically. The singing to the note and maybe kickoffs and all he wants exactly the same. You can kind of put your own touch on the break, I guess.”

But Jim Mills was free to break new musical ground for himself back in February of 1989, when he went into the studio with the band to record an all-gospel album, “I Heard The Angels Singing.” “I think it’s a good one,” he says.

Jim Mills talks about life on the road as if anyone would be envious of the countless hours on the highway and sleeping in bunks on a bus three or four nights a week. “We all get along real well,” Jim notes. “We eat together, we sleep together … I see more of them than I do my own family.” When the band isn’t on the road, the big Silver Eagle bus is kept in Bristol, Tennessee, where Doyle Lawson lives and the band members drive in each week from wherever they make their home. It’s about a four hour drive for Jim as it is for Ray Deaton and Russell Moore who both live in Georgia. When they aren’t on the road for whole weeks at a time the band members often have three or four days of the week to spend at home before they are back on the road once again. In 1988, the band played one hundred and seventy-some dates. That’s just the dates they played—not counting the time it took to get there. They put 140,000 miles on that bus.” The band members take turns driving, often all through the night to get to the next show. Jim expresses no regret that he will be unable to drive the bus until he’s 25 years old as stipulated by the band’s insurance policy. Jim’s father interjects, “Doyle said he’d never let him drive the bus because he’s got a bad habit: every time he laughs he shuts his eyes. Doyle says he afraid somebody will tell a joke while he’s driving.”

The band’s busy schedule permits them little time to practice or rehearse. “For instance, this weekend we played in Brookeville, Indiana, one night, left there about one o’clock in the morning … We had to be in Virginia Beach, Virginia, the next day at one o’clock p.m. to make the show … We got there at 12:30. You don’t have time to do much practicing. I try to pick some every day, maybe two or three hours a day.” When the banjo is not around his neck, Jim still occasionally finds time to go quail hunting with Kate, his beloved English pointer, go bass fishing, or tend to his antique pocketknife collection.

Does it bother Jim that, even given the most grueling of work schedules, all too few bluegrass musicians have ever become rich? “No, you have to hope high.” His father adds; “Jim is a good candidate to make it, as tight [with money] as he is.” Says Jim: “Doyle told me once that he thought J.D. Crowe was the most thrifty banjo picker he’d ever met ’till I came along!”

Jim is much more ready to thank everyone he feels has helped him along the way than he is to take credit for his accomplishments. “I owe a whole lot to my mom and my dad as well as my step-mom and step-dad because they always supported me one hundred percent . They never discouraged me from picking at all . . . and the only job I ever had was playing music since I was about fourteen.” Jim says he also is especially indebted to J.D. Crowe with whom he was recently- able to swap banjo secrets for five hours while their bus was stuck in a Georgia traffic jam, a fortuitous delay from Jim’s point of view.

“I’m really having a ball,” Jim says of his bluegrass career. “I’m happy where I’m at.” When asked to describe the rewards of his profession, Jim nearly waxes poetic: “When you’re up on stage and you’ve got a good P.A. system, a good sound man and a good audience, when you hit that last note on that last song and get a standing ovation and Doyle looks over at you and smiles … offstage there are five or six people that want to shake your hand or pat you on the back and tell you that you did a good job—it makes the sleepless nights, the long roads and the bad colds all worthwhile.”