Home > Articles > The Artists > Jerry Douglas

Jerry Douglas

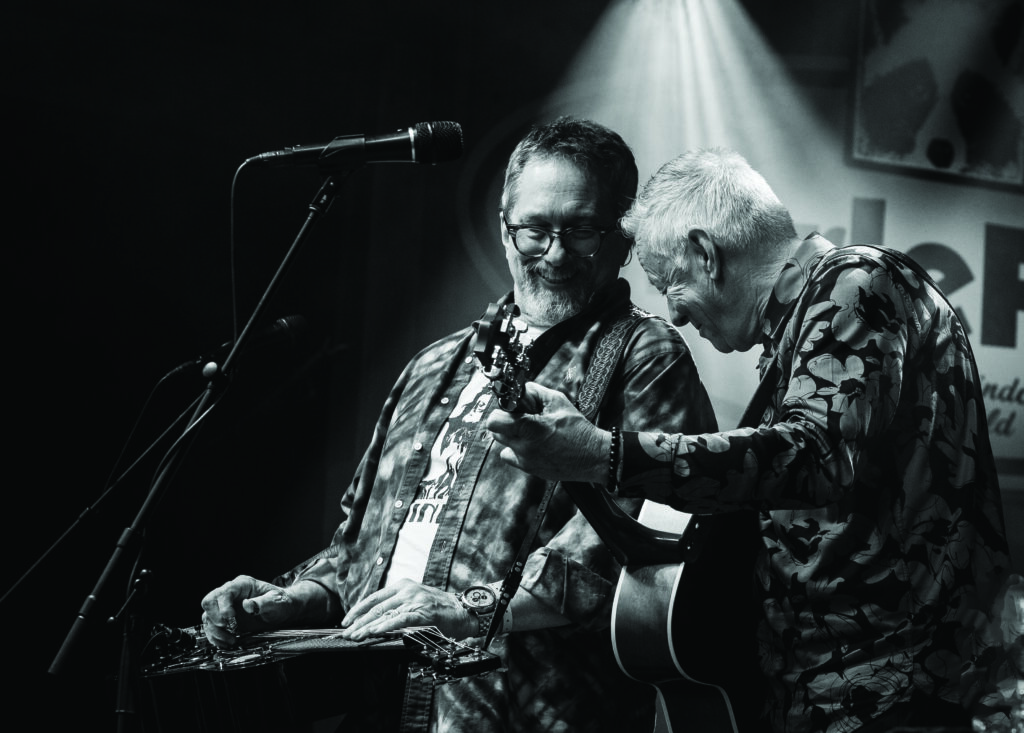

Photo by Scott Simontacchi

One of the most innovative musicians and gifted producers of his generation, Jerry Douglas is at the point in his career of fifty years when he can do whatever he wants. A fifteen-time Grammy winner and the ten-time recipient of IBMA’s “Dobro Player of the Year” award, Douglas—along with Josh Graves, Bashful Brother Oswald Kirby and Mike Auldridge—is probably the most influential resophonic guitar player in the history of the instrument. There are other fine Dobro players on the scene, but most would tell you they’ve been inspired by “Flux,” the nickname given to Douglas by Ricky Skaggs during their tenure with The Country Gentlemen.

A three-time CMA “Musician of the Year” award recipient in 2002, 2005 and 2007 and the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Artist in Residence in 2008, Douglas was also recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts with an American Heritage Fellowship in 2004. In 2011 he was honored by the Americana Music Association with a Lifetime Achievement Award. He has been nominated for thirty-two Grammys—so far.

As a solo artist, the Jerry Douglas Band combines elements of country, bluegrass, rock, jazz, blues and Celtic music into their critically acclaimed sound. In recent years bluegrass fans have fallen in love with the Grammy-winning The Earls of Leicester, who honor the music of Flatt & Scruggs. Douglas co-founded the Earls in 2013 with fiddler Johnny Warren, Charlie Cushman on banjo, Tim O’Brien on mandolin, Barry Bales on bass, and Shawn Camp on guitar as the voice of Lester Flatt.

Jerry continues to be an in-demand sideman, session player and producer. In addition to 16 solo albums, he has played on more than 2000 recordings with everyone from Garth Brooks, George Jones, Paul Simon and James Taylor to Eric Clapton, Emmylou Harris, Ray Charles, Dierks Bentley, Elvis Costello, and Tommy Emmanuel, among others. Bluegrass fans have been entertained and mind blown since the mid-1970s by Jerry’s live and recorded music with the Country Gentlemen, J. D. Crowe and the New South, Boone Creek, the Whites and Alison Krauss & Union Station, plus numerous other collaborations and his solo work.

Douglas has produced works for Krauss, the Del McCoury Band, Maura O’Connell, The Whites, Jesse Winchester, the Steep Canyon Rangers, The Gibson Brothers, Eric Clapton, The Brother Boys and Molly Tuttle, among many others—several earning top awards and platinum sales. He has served as the co-music director of the acclaimed BBC Scotland TV series, Transatlantic Sessions, since 1998. Jerry also was featured as the Artist in Residence at the 2022 and 2023 Grey Fox Bluegrass Festivals in Oak Hill, New York, and he is the host of the annual Earl Scruggs Music Festival in Tryon, North Carolina during Labor Day weekend.

Jerry Douglas doesn’t take his success for granted. He is the kind of artist who walks around the festival groundsafter a set and talks to his fans. Dogs like him. “I think dogs are empathetic,” he said. “They soak the poison out of you,” he laughed. “They’re happy to do it!” Douglas still gets excited about the next performing or producing gig, and he loves playing music as much as ever. He is confident without being an egotist, something his dad cautioned him about when he was a boy in Warren, Ohio just learning to play.

Bluegrass Unlimited caught up with Jerry to talk about what energizes and inspires him now in the music world, just before he was heading to the 2023 MerleFest in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, to celebrate what would have been Doc Watson’s 100th birthday.

The Earls of Leicester

Jerry always looks like he’s enjoying himself onstage, but fans say they’ve never seen him smile as much as when he dons a white shirt and black string tie to take the stage with The Earls of Leicester, playing the musical role of Josh Graves. “It’s all about being Josh Graves to me,” Jerry says. “It’s special to play with The Earls. I’d been thinking about a band like that for a long time before I ever thought to put it together—to just be able to play that music again because I thought it was missing from the landscape. I knew Johnny Warren and Charlie Cushman were shoe ins for it. The mandolin and guitar players were the hardest parts to find.” Tim O’Brien originally played the part of Curly Seckler on mandolin, followed by a handful of subs and then Jeff White.

Jerry’s wife, Jill Douglas thought of Sean Camp for the guitar spot. “He showed up with the tie and the hat and the suit, ready to go,” Douglas said. “He sounded like Lester. He channeled it all, and that sealed the deal for me. Barry Bales has always been the steadiest, rock-solid bass player that I could think of, so he was going to be Cousin Jake [Tullock].”

The Earls have turned into a long-term band, rather than just a side project. “It’s kind of cast in stone,” Jerry said. “Daniel Kimbro is our bass player now. He plays with me in about every iteration that I have, and he’s another rock-solid guy who went to school on Barry Bales and Todd Phillips, plus the older bass players like Cousin Jake.”

The Earls of Leicester play in the style of Flatt and Scruggs, bringing the legendary repertoire and vibe to a generation who never heard them live. In fact, Jerry and his peers are now Flatt & Scruggs-level heroes to the youngest crop of bluegrass stars and up-and-comers. “We are those people to them now,” he observed, humbly, “and it’s a strange position to be in. I hoped that when we put that band together and got it out there, that people would go back and re-visit the Flatt & Scruggs catalog. It makes me feel like a little kid again, being onstage with that band. That’s why I smile so much. It’s a dream come true for me.”

Alison Krauss & Union Station

When asked what he loves most about playing with AKUS, a gig he has had since 1998, Jerry said the group is like a sculpture. “There are so many moving parts, but it’s all in one case like a watch with gears that move in synchrony, backing this VOICE that happens only once every century or so,” he said. “I also think the band is like painting… I pay attention to the lyrics and try to put the right touches around her voice, to keep everybody involved in what she’s saying. I think the whole band does that. Barry Bales is the bedrock, and then Dan (Tyminski) and Ron (Block) and I are the guys who just sort of float around it. It’s a special thing. Even if we haven’t played as a band for a couple of years, we get together and from the first beat it sounds like us.

AKUS is a perfect example of a band that is greater than the sum of its parts. “It’s like her voice is sitting on top of the Christmas tree.” Douglas said (no relation to the fir trees). Krauss and the band have recorded a set of new songs, and they’re contemplating touring again. All the band members have musical sidelines, but AKUS remains top priority for them all. Hopefully something will work out soon.

Tommy Emmanuel

“I’ve gone a lot of places with Tommy,” Jerry said. “Tommy is like the Energizer bunny—he and Sam Bush; they never stop going. They’re dynamos, and Tommy’s touring world is everywhere. I have toured Australia with him, Italy, and this year we went to Iceland. We’ve toured together all over the U.S. as well. He’s amazing. Of all the great guitarists I’ve played with, I’ve never heard anybody able to play that much guitar and combine that many different genres of music all in one solo! Chet Atkins gave him the CGP title (Certified Guitar Player) years ago.”

For years Jerry has kept a running dialogue on the Kayak travel search engine for a ticket to Reykjavik. “I’ve always wanted to go to Iceland,” he said. “I didn’t know I would get to do it this way. How cool is that? It was a guitar workshop, so I just walked around and burst into different guitar clinics and rooms to add my .02. It was a lot of fun!”

John Hiatt

John Hiatt and The Jerry Douglas Band collaborated and released the album Leftover Feelings in 2021 for New West Records. Their project, recorded during the COVID pandemic at historic RCA Studio B in Nashville, was followed by a Hiatt/JDB tour to promote the release. Additionally, the documentary, Leftover Feelings: A Studio B Revival (2021), directed by Lagan Sebert and Ted Roach, chronicles the work and process.

“John and I have been friends since we both took part in Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume 2 for the Dirt Band in 1990. John’s songs have been cut by practically everyone you can name—bigsongs and songs in movies, things like that,” Jerry said.

“Leftover Feelings is a wonderful record,” Jerry continued, “and I am proud of the documentary, as well.” The tour to support the record took place as the pandemic was slowing down, at a time it was OK to go out and tour, though with restrictions. COVID protocols deemed audience size to be limited according to size of venue, and audience masking was required. We were on that first wave where people could get out and hear live music and everybody was happy to be there, audience and musicians alike. We were ecstatic to be doing our jobs again.”

The COVID Curve

COVID 19 threw a curve in every musician’s ballgame. “I have a studio, so I was able to work all through it,” Jerry said, gratefully. “I probably played on fifty different records in that year and a half span, but I was getting things that I normally wouldn’t get because I think everybody knew that every musician in the world was just sitting somewhere, available. I was doing records for people like the guy billed as ‘the Bob Dylan of Venezuela’ and a great deal of really cool world music. I did a few bluegrass records; I think Lou Reid recorded during that time. I have a hard drive that just says ‘COVID’ on it, with everything I recorded during that time. I’d sit up in the studio and I could engineer the things myself. I have good microphones and good gear, so I could make quality recordings.”

He also played for his fans on Facebook via live-streamed videos every Friday at 1 p.m. “People were tuning into Flux Fridays,” he said, “but I didn’t put out a tip jar. Anyone who wanted to send money, I sent them to IBMA, the Bluegrass Trust Fund, or the Recording Academy’s MusiCares program. All my neighbors knew about it, so they didn’t mow their yards from 1-3 p.m. Somehow I emerged from COVID and was even able to get some funding for the Earls and for my band, so nobody had to go on unemployment.”

The Transatlantic Sessions

Douglas and Shetland fiddler Aly Bain co-produce the annual Transatlantic Sessions. “It was really Aly’s brainchild. He thought of bringing musicians from America and Ireland to Scotland and throwing them together. It’s a collaboration of Celtic, bluegrass, and the traditional music where the artists come from. I brought Sam Bush and Bela Fleck over for one of the taping years. We do it as part of this festival called Celtic Connections that happens from the middle of January through the first week of February. I get the roster for the show and ask everyone to send me five or six songs. By the time I land in Glasgow, I have a set list, and we rehearse that. I’ve been doing this a long time, so I know how to make a set list,” he smiled. “This year we had Martha Wainwright and Liam ó Maonlaí from Dublin, best known as a member of Hothouse Flowers. We also had Allison de Groot and Tatiana Hargreaves from out in the Northwest, and Allison is from Winnipeg. So, there was Gen X and Millennials and old folks, all smashed up. We did two nights at the Royal Concert Hall in Glasgow, and then we went on the road to seven different cities in Ireland and England. We played the Royal Festival Hall in London this year, and Eric Clapton showed up and played on the last night.”

Producing Music

Douglas says he likes the role of producing because “instead of playing the Dobro, I play the band. It’s like being a movie director, a referee, a casting director and a psychologist. I’ve been doing this for so long, that I just I have an encyclopedia of knowledge,” he continued. “I am happy to share any of it at any point.”

For example, “Molly Tuttle writes these great songs,” Jerry said, “and she writes all kinds of music. She decided to make a bluegrass record, so she asked me to produce.” Molly wanted to bring Ron Block on the project, and Jerry remembered producing an album with Tina Adair years ago for Sugar Hill. “It was a beautiful record that didn’t get any traction, but I remembered, and I thought her voice would go great with Molly and Ron. Then we had different people come in.”

Douglas read a review of Molly’s 2022 Bluegrass Grammy Award-winning album, Crooked Tree, in Bluegrass Unlimited. “The reviewer said we used synthesizers ‘probably inspired by a Billy Strings record.’ All that is false,” Jerry said. “I made something we called a ‘fiddle cloud,’ where I had Darol Anger, Jason Carter, Bronwyn Keith-Hynes and Christian Sedelmyer play sort of the same part, but not at the same time.” The fiddle cloud effect was used on a song Molly wrote about the first time she played at Grass Valley, a long-established festival produced by the California Bluegrass Association on Father’s Day weekend. “It was this big, mysterious cloud,” Jerry said. “We did things like that to set the mood and set you right down inside the song.”

Douglas produced a second bluegrass album with Molly Tuttle and Golden Highway which has just recently come out, called City of Gold (Nonesuch/Warner Music). “We did some of the same kinds of things on it,” he said. The new album is “totally bluegrass,” Jerry said—“probably even more bluegrassy than the first one. It’s with the band and their whole take on Molly’s music. Dom (Dominick Leslie)is playing so well, and Bronwyn is killing it. Kyle Tuttle surprised me the most with his great studio savvy. As a producer, I turn over every stone. When anybody brings an idea, I’m going to try it because it might be the one that ‘makes’ the record. I’ve got my own ideas, but I try to see the big picture as well as the minutiae—the backup vocals, repeating lines, and choosing the interval between songs. I like to let the listener finish a thought at the end of a song rather than go to the next song too quickly.”

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when Jerry started producing the Nashville Bluegrass Band, his goal was to be able to play a NBB cut after something like a Garth Brooks record and have it stand up against the more expensively produced country song in quality. On a lot of early bluegrass records, they didn’t pay attention to the bass,” he said, for example. “They just featured the front and middle of everything. I think we need to include the edges. We need to hear the whole thing.”

Jerry has produced all kinds of records for various people. “I went in with the idea of what the finished record would sound like before we even started. I wanted to hit all the high spots and low spots and create a whole body, a shape of a record.” It’s different now,” he said. “Fans can buy Del’s ‘Almost Proud’ single online if they want to. You used to have to buy the whole album to get the song you liked, and that’s when concept albums were made. One idea flowed through the whole record. We’ve probably got to change the way we record,” Jerry said. “Going in and recording 11 or 12 songs is not financially advantageous. With the Gibson Brothers, we did cut the entire album in two sections. That was a pandemic record, started at the Sound Emporium in Nashville. They closed the studio in March of 2020, and then we came back with Bil VornDick and finished the record two years later. It was a collection of new songs Eric and Leigh had written. Some sounded like they’d been written in the ’50s, and some sounded like the lyrics could be happening right now.”

Jerry likes brother harmonies, which brings to mind the Rose of My Heart album by the Whitstein Brothers for Rounder in 1984. “I remember doing vocals one day, and I had this huge foam rubber baffle between them so I could record them both at the same time without having the sound bleed from one mic to the other,” Douglas remembered. “I looked out there and one of the brothers had reached over and was holding the shoulder of the other one. They locked their breathing. It was perfectly matched. Singing harmony that close is a DNA thing, like the Isaacs, the Everly Brothers, the Osbornes. To see the Whitsteins do that was bone-chilling to me. I thought, ‘Man, this is the stuff. Everyone should be able to see this kind of thing.’ Producing records for me is all about that. It’s about what’s going on with the band, how they’re feeling. You get in the studio with a band or an artist, and you all become family. I love every part of making records—choosing microphones for instruments, choosing the right room to record in, building a room for somebody to be in, how to handle separation … I don’t like to make perfect records. I like leaving some of the bark on the tree.”

It’s been rewarding for Jerry to mentor young artists in the studio and help them move up to the next level. “It doesn’t just step them up,” Jerry clarified. “It steps me up, too. I learn something every time I go in there. The younger, newer bluegrass artists are making records that take their whole world into account when they’re writing songs. Especially Molly—she’s got big ears. She listens to all kinds of music, and you can hear it in her guitar playing and singing, the way she sings a song, and what she writes about. I enjoy it very much. I feel very fortunate to be involved at this point of my career with somebody that’s cutting it.”

Advice and Lessons Learned

Jerry is willing to share what he’s learned because he had band leaders and peers who did the same thing for him. “My dad had a great band, and then I got to play with a band like he dreamed of having. I remember him going away to see the Country Gentlemen in 1963 or ’64 in Cleveland. He came back, and it was like he’d had a religious experience. They were the New Grass Revival of that period. Then came the New Grass Revival, and then came everything after that which would stretch the boundaries of bluegrass music.”

Jerry thinks bluegrass is “a geographic music. Bands in different parts of the United States or in different countries have their own way of performing their own songs. You can sort of hear it. But bluegrass is also a very inclusive world. It hasn’t always been, but it has become that, I think, because of bands like the Country Gentlemen, the Seldom Scene and Joe Val. It was a music that was handed down from the generations before, but they also picked up a lot of new things—like a rolling snowball. Their music picked up the things that were happening around them.

“Charlie Waller was one of the sweetest people that ever set foot on the earth,” Jerry said about his boss in the Country Gentlemen in 1974. “He was great to me, but so was Doyle Lawson, and so was Bill Emerson. Bill was very instrumental in hiring me, but at the same time he was going to the Navy band.

My dad told me a long time ago, “You’re only as good as the people you’re playing with. When I would leave the Country Gentlemen and go home and play with my dad’s band, I sounded like my dad’s band. When I got with David Grisman and Tony Rice, then I would rise up to that level. If you listen to them, you start to sound like them. It was the same way with Ricky Skaggs and with J. D. Crowe, a firebrand, iconic banjo player. With J. D., it wasn’t so much what he told me, but what he did that I followed. J. D. Crowe was not the emcee. He didn’t speak on the microphone. He sang baritone in the trio, but that banjo was the leading force in that band, and our sound was built around his career and the songs he had played, and his time with Jimmy Martin. A lot of things transferred.

“I was so lucky to play with guys like Charlie Waller, Doyle Lawson, Bill Emerson, Ricky Skaggs and Buck White,” Jerry continued. “When I played with The Whites, they were as much my family as my real family. They came to Virginia with a U-Haul trailer and a truck and a van and moved me to Nashville in an ice storm. How big is your heart, to go do that kind of thing for somebody? Sharon and Cheryl became the sisters that I’d never had, and Buck was my father. They were heavily involved in their church, and I got involved there, too. It was part of them, so it became part of me. And it translated onstage as a family—a family that could really play well.”

Jerry said playing with The Whites gave him “a shining example” of great singing that taught him how to back up vocals. He was also influenced by Vince Gill’s singing. “I met Vince when he was 14,” Jerry said. “He was great then, and he’s great now. He is one of the people who has not changed one iota since the first time I met him. He’s the same guy. None of his success went to his head. My dad told me, ‘Don’t ever let this go to your head. You’re good. You’ll hear it a lot that you’re good.’ But he said, ‘Don’t get the big head.’ That, to me, meant, ‘Don’t let this take away your compassion for other people, or for other people learning the same instruments that you play. You’re not better than them. Everybody’s the same, but some people’s skill level is just a little higher. And why not impart that wisdom to somebody if they want it? Be an open book about this stuff. Bluegrass is a music where the artists are very accessible to the audience, for the most part.

“I love walking through a crowd,” Jerry continued. “I don’t mind people saying, ‘Hey, man—loved your show last night! Looking forward to your show later on! How’s Tony Rice doing?’ I still do it. It’s where I came from. It’s a connection for me. I was at the festival in Berryville, Virginia every 4th of July from 1967 or ‘68, on. I remember when J. D. Crowe came with Doyle Lawson, Larry Rice and Bobby Sloane, and everybody was waiting for them to show up because they knew these guys were just going to blow us away. And they did. It was like the Beatles hit the stage. And then to be there in 1975 in that band everyone was waiting to see with Tony and Ricky and J. D. and Bobby—it was fantastic. I was only in the New South for six months, but it felt like years because of what I got to do with them. We went to Japan, and we made an album. I left Country Gentlemen to move to Lexington, Kentucky to play with Crowe and Tony. Then Tony was going to go with David Grisman, and Ricky and I had always wanted to have our own band and it seemed to be the time to make that break. It was hard for me because I really loved J. D. Crowe as a fan, and I still do. Always will. He was nice to me. He never said, ‘Don’t play this.’ He would say, ‘Listen to the band. Follow the dynamic of the band.’ I learned that if I couldn’t hear someone’s solo or the lead singer, I was playing too much or too loudly. If you’re not part of the band, you’re not in the band. At that point you’re somewhere else, getting in the way.

“This was something Tony Rice knew, too,” Jerry said. “He told me, ‘Don’t be practicing your next solo while the verse and chorus are going on, right before your solo. Just play it like it’s the last solo you’re ever going to play. Play every solo that way.’ That’s some of the wisdom that stuck with me, from good band leaders. Earl Scruggs was a very quiet man, but when something needed to happen, he would say something. If you watch those old Flatt & Scruggs TV shows, you knew who was going to play the next solo because he backed the verse before it. They were in line, like a baseball team.”

Being the Front Man

What’s different about fronting his own band, as opposed to being a sideman? “I like the audience to be as involved in the music as the band is, so I’ll joke with them. I think in those situations, the audience gets to know me better. They get a little more insight into me than if I’m standing up there with Alison. In her band I’m going to be quiet because I’m a sideman. Alison wanted me to emcee when I first joined Union Station, but I told her, ‘I think they want to know what you have to say. They want to know you,’ and that’s when she started emceeing the band. She says some crazy things onstage. She’s funny, but that’s really her. She is a quiet person, but she’s got this quirky personality, and it comes through onstage, When she talks about things like ‘Mushroom Soup, the staple of our nation’—things like that, it’s hilarious. There’s stuff going on up there that no one knows about, that is just funny and keeps us grinning and in tune with each other. Adam Steffey emceed for Union Station for several years, “and Alison just stood there,” Jerry said. “There was a lot more inside there than people knew, and I think it’s cool to have a little window into her world and know what she’s like. I get to do that with my band, and with The Earls of Leicester.”

As for his place in the bluegrass world today, Jerry Douglas said, “Well, I come and go to and from that world. Bluegrass is the most important thing to me as far as the music goes, but I love where it’s taken me. I love all the places that it’s let me go, especially as a Dobro player, because it’s a very emotional instrument, like a violin or the human voice. I’ve learned things from bluegrass musicians at a very high level, but that doesn’t mean I can’t still learn something from a rank beginner. I think we can all learn from each other.

“I think it is important for musicians to remember these things: Just stay in the band. Keep your head in the band. And whatever you’re doing, if you’re playing a solo, think about the person that’s listening to you as well as what you’re doing. If you keep them involved, your show is going to turn out a lot better.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Very interesting, thanks.

The Great Dobro Sessions disc inspired me to play the reso.