Home > Articles > The Tradition > J.D. Crowe Remembered

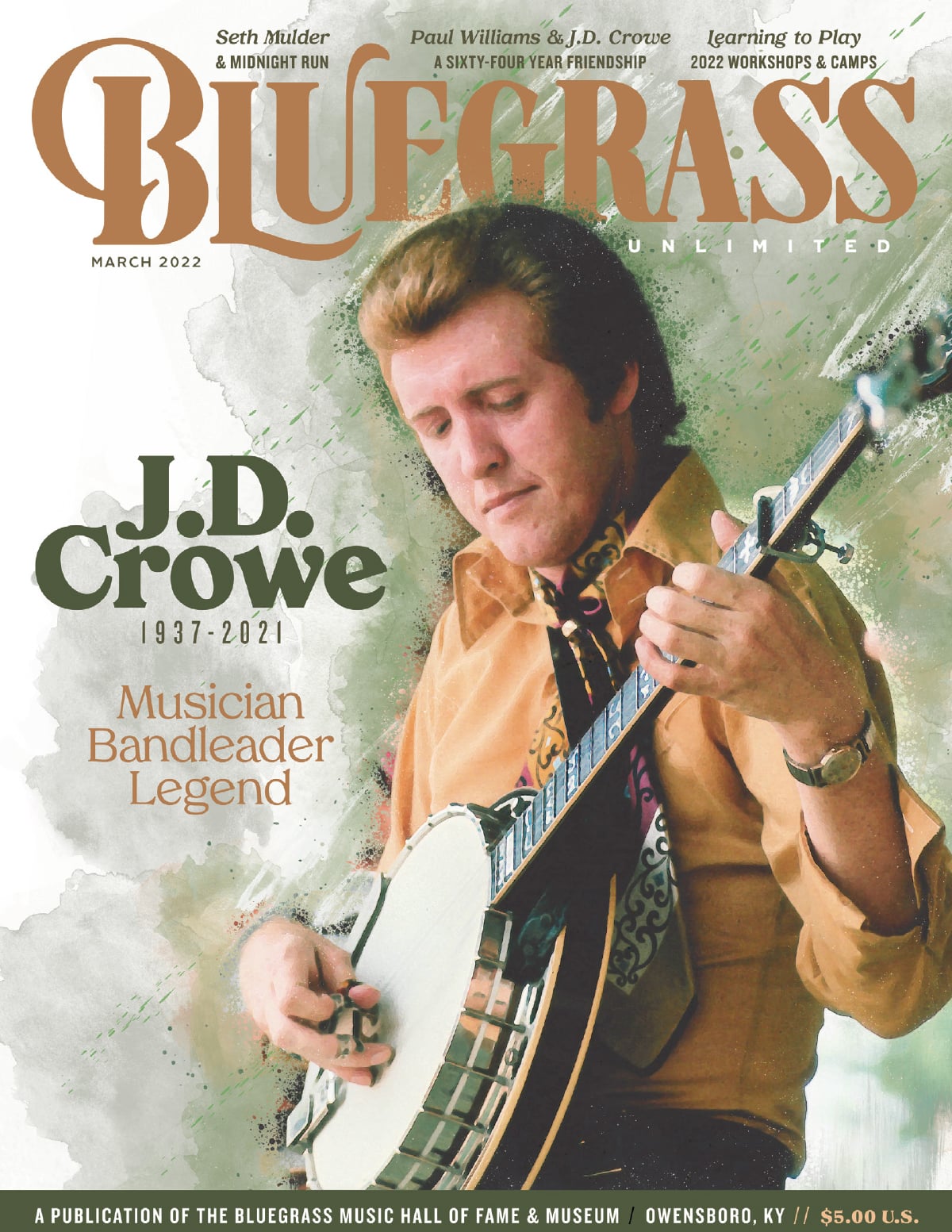

J.D. Crowe Remembered

By Some of the Best Musicians in Bluegrass

My first opportunity to see J.D. Crowe perform was at the Stone Valley Bluegrass Festival, a short-lived event that took place in the late 1970s alongside the beautiful Whitewater River near West Harrison, Indiana. I did not get to meet Crowe, however, until almost 20 years later.

It happened at the second-ever Tall Stacks Steamboat and Music Festival, a marvelous occasion that began in 1988 as a celebration of the bicentennial of the Ohio River city of Cincinnati, Ohio. The festival took place every three years, bringing in 20-plus riverboats from all over the U.S. that docked together along the shoreline, which was interspersed with multiple live music stages built on both sides of the river.

It was mid-October and Crowe and his band The New South were scheduled to perform outdoors on the Northern Kentucky side of the festival. But, an unusually-early Alberta Clipper cold front had arrived overnight, blowing in fresh from the Arctic Circle. By noontime the next day, the temperature had dropped over 40 degrees compared to the day before. Even though it was a sunny day, the early-wintertime conditions were not conducive for playing live music.

I happened to be hanging out with the future IBMA Hall of Famer John Hartford that day along with Cincinnati bluegrass legend Katie Laur, with all three of us standing back in the crowd in front of Crowe’s stage. Eventually, a little ways into his set and trying to perform with no heat source, Crowe asked the crowd if they had any requests. At this point, the air was so frigid that the band member’s fingers could barely move.

Hartford, ever the prankster, tried to change the sound of his well-known voice and kept yelling out for the band to play “Train 45,” an uber-upbeat bluegrass standard that would be hard for frozen fingers to pick. Crowe tried to ignore the suggestion, yet Hartford—bending low so as not to be seen—was incessant in his request for the super fast tune. Crowe finally caught eye of Hartford, called him out from the stage, laughing, and he played the song anyway, doing the best they could to make it sound right.

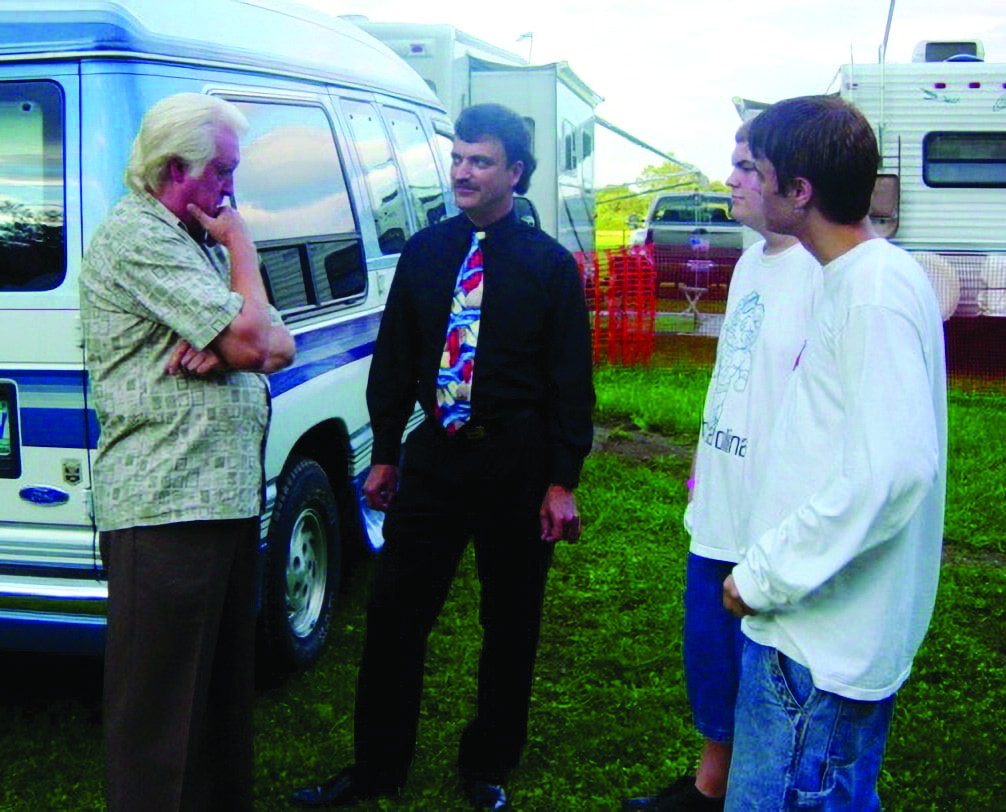

Fast-forward eleven years later to the year 2002. Hartford had died one year earlier in 2001, which is the same year that I began to pursue my career in music journalism. I was backstage at the all-star Tribute to Earl Scruggs show held in Dayton, Ohio, and hosted by Joe Mullins. As Crowe and Sonny Osborne are trading stories in the green room, talking about old lost tunes and artists such as Thumbs Carlisle, they begin to talk about Hartford and that is when I found myself backing up J.D. on his story about that cold day on the Ohio River. From then on, Crowe and I became friends.

I was living in Cincinnati at the time and Crowe was residing an hour and a half away in Lexington, KY, so I had the opportunity to see him perform often in the early 2000s. Luckily, after doing a definitive interview with him in Gritz Magazine in 2002, I was always invited backstage to hold court with J.D. and catch up on life and share a joke or two.

When I moved to the mountains outside of Boone, NC, nine years ago, however, I rarely if ever saw J.D. again. After learning of his battle with COPD, I didn’t want to tax him with a phone call. When word came of his hospital visit and his death a few months ago, it hit me hard just like it did for bluegrass lovers of all ages. Not only had a friend passed away, but I realized that one of the greatest musicians in the history of bluegrass would never play again.

There are many folks in the bluegrass world who knew J.D. Crowe better than me, of course, especially those that got the chance to perform with the man over the years. So, here in this tribute article, I asked for and received responses to Crowe’s passing from acclaimed musicians Ron Stewart, Sammy Shelor, Béla Fleck, Wyatt Rice, and Rickey Wasson along with Ricky Skaggs and Jerry Douglas, the latter two now being the last living members of that legendary “Rounder 0044” band.

When musicians of note are old or sick and in a bad way, many thoughts enter our mind concerning their welfare. But there is something different that happens when that person dies and the finality of the situation kicks in. There will be no more last words or last notes played, it is over.

Below, I asked each of my guests the same first question; ‘What were your thoughts when you heard that J.D. Crowe had left this world?”

Jerry Douglas

“My first thought was ‘God bless him, he’s suffered enough.’ He had half a lung taken out when he was about 17 years old and it was a family genetic thing. I knew he had been sick a bunch and whenever I’d go up there and play, he’d want to come out but he couldn’t because of the weather or one thing or another. I just thought, ‘Crowe has become this amazing icon in this certain kind of music while fighting this whole other thing in his life with his lungs, just trying to breathe and sing and do all of these musical things.’ I was glad that he didn’t have to suffer anymore. But dang, I missed him immediately.

“I didn’t stay real close to him all of the time, but every time that we talked it was friendly and we were right back where started,” continues Douglas. “He and I never had a negative word or look or any kind of weird thing ever between us. He was like a great friend from the beginning, but he was also a hero to me before I ever played with him or met him. I remember being at the Berryville Festival when Crowe and the Kentucky Mountain Boys played with Doyle Lawson and Larry Rice and Bobby Slone and the whole festival was waiting for them to play because it was like, ‘Here comes the tightest band in the world.’ These guys played the Red Slipper Lounge in Lexington six nights a week so they were tight. Doyle was one of the best rhythm guitar players ever. I remember watching it while just a kid and when those guys played, they blew the place up. It was like The Beatles had landed at Berryville or something. And then, a few years later while still a kid of 19, I got to go and play the Dobro with J.D. and Tony Rice and Ricky Skaggs and Bobby and the same thing happened, as in whole festivals were waiting for us to play. We were ‘The Beatles’ that year. It was surreal for me to be there at the same Berryville Festival where I had seen so many great groups as a kid, and now I was in the band and a part of it.”

Ricky Skaggs

“I had been texting back and forth with my friend Steve Chandler, who was really close to J.D., so we knew he had been sick. Russ Carson and I, my banjo player, we had planned on going up to see him as soon as he got out of the hospital, but with COVID going around, I knew that they wouldn’t let us in to see him. Nobody but family. We even got word to his son David that we wanted to come up and see him and they were fine with it. But, I think that once J.D. got home, he started going downhill and they brought hospice in to watch him. We wanted to love on him and say our goodbyes, but we didn’t get a chance to do it.”

“J.D. and I had a great friendship and a great relationship even after I left his band and started Boone Creek with Jerry Douglas,” continues Skaggs. “We never had any bad words. J.D. had so many band members go in and out over the years, it was like, ‘OK, thank you very next.’ I knew that J.D. would have a good band because he always knew how to pick guys that could play rhythm and sing lead. But, I sure am glad that I got to be in that band with him and Tony and Jerry and Bobby Slone. I just realized the other day that Jerry and I are the only ones left from that group. Right after J.D. passed, I got to thinking, ‘Wow, seeing Tony go and J.D. go almost a year apart, that is really tough.’ I didn’t get to talk to J.D. right after Tony passed away, but we did see each other at one of those Sonny Osborne lunches that if you got invited to, you just needed to go. It was a great thing that happened down here in Hendersonville as Sonny would hold court at the end of the table at this big buffet restaurant they have here in the Rivergate area. J.D. would try and come down for that, although not every month, but he did come down quite a bit for the luncheon and I got to go to that a few times. It was great fun.”

Ron Stewart

“First of all, news of J.D.’s passing was a huge shock, but mostly I felt broken-hearted. Crowe was like an uncle to me, and just about anybody who has ever worked with him will tell you the exact same thing. He was like family, so it goes beyond the music, obviously. He was just a great guy. It’s a devastating loss for the music world, but more importantly, he will be missed by anyone who knew him, especially his family. And, it is wild to think that he has played his last tune. The other thing that I think of is that Rickey Wasson sent me a copy of that new Crowe & Wasson album about a week or two before Crowe passed away. We recorded that album with him in 2018 or so and Crowe was still playing very well at that point. The one thing about Crowe, and a million people will tell you this; nobody had that tone that he played with, and he had that tone until he died. He could just pick up the banjo and start tuning it and he would have that tone. No one else in the world had that same tone.”

Béla Fleck

“My first thought was regret; regret that I had not had the chance to become better friends with J.D. I moved to Lexington in 1979, basically to be in his orbit and to learn from him and from the scene around him. I spent a lot of time listening to him play and was always thinking about him, yet we never became close, although we were always cordial. Just a couple months ago, I was playing in Richmond, not far from where he lived, and I thought about calling him, and now I wish that I had done so.

“Being a Yankee banjo player from New York City, I felt like I wanted to learn from guys like J.D., and I also guess I wanted some validation or acceptance from the southern bluegrass cats. So, I was a little unsure and unconfident. But, I learned so much from watching and listening to J.D. Every chance I got, I would go and see him play, often at the Post Lounge at the Holiday Inn North on Newtown Pike, where he’d play three week stints. I’d be there every night when I wasn’t on tour, trying to understand everything about him. J.D. was the standing master when I came onto the scene. He had the drive and the tone, he played the great old banjos, and he was just a cool dude. There were other giants out playing at that time. Sonny Osborne (J.D.’s hero) was still playing his awesome brand of banjo then as was Bill Emerson, Eddie Adcock and others. But J.D. was the one we all watched. There was just something about him. I used to love playing the same festivals he was on. On Friday night, he’d sound a little rusty, on Saturday he sounded great and by the Sunday afternoon set, it was truly magical. I don’t think he warmed up much in those days, but by Sunday; holy cow, was he ever hot!”

Sammy Shelor

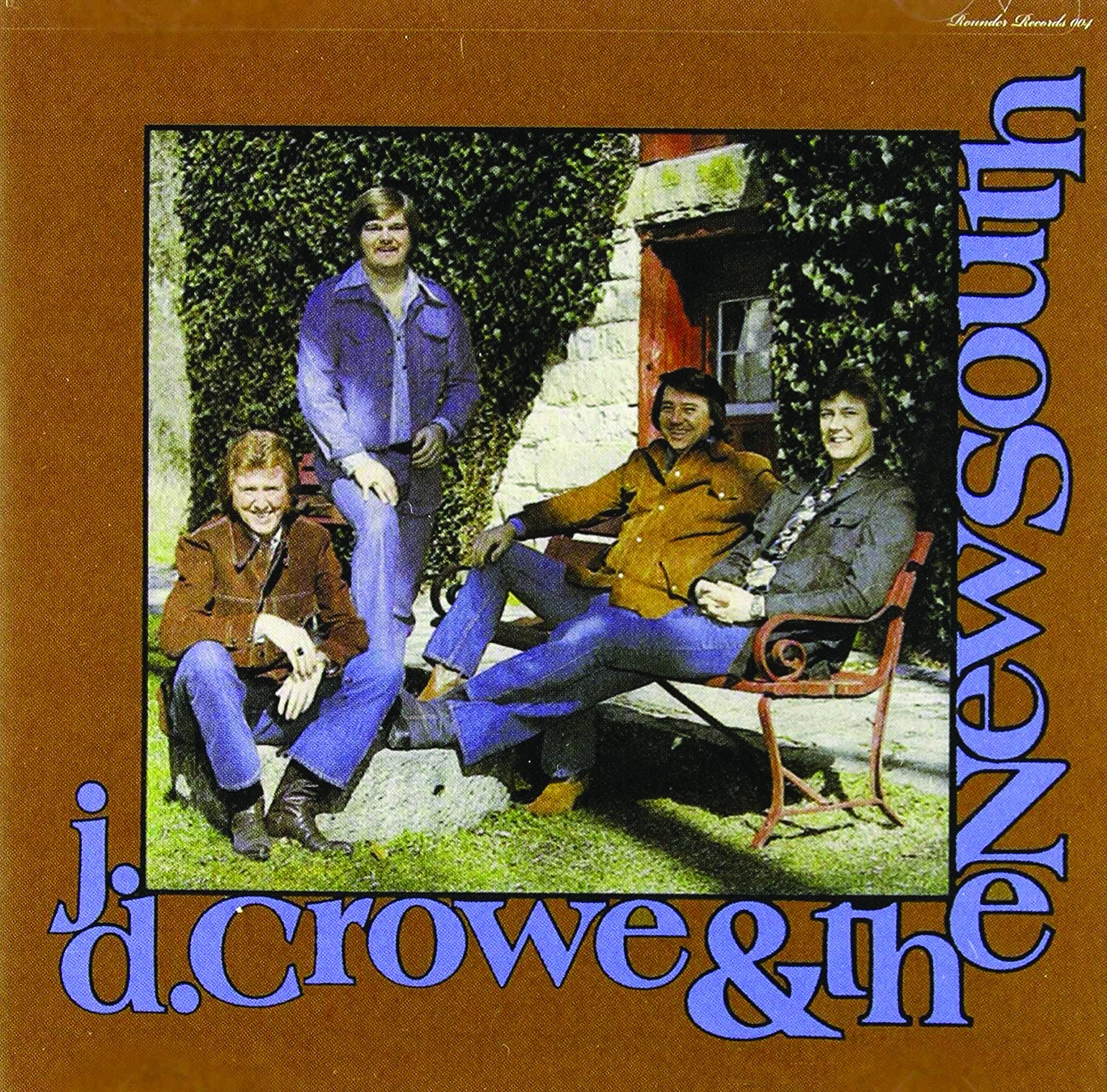

“I was out playing the banjo by the time I was ten years old. About 1972, a friend of ours, a guy I met who was a school teacher named Leon Pollard up in Patrick County, Virginia, he came up and started talking to me and took an interest in my playing. He had a little local band at the time and one day he said, ‘Well, come on over to the house and we’ll jam sometime.’ So, I started playing with this adult band when I was 10 years old and they were the best people in the world, but I couldn’t play that well back then. But, they just enjoyed playing music and they would do four to five shows a year locally and I was the novelty, the ‘ten year old banjo picker.’ Anyway, Leon had the greatest record collection of anyone that I’ve been around in my life, and still does. I had an 8-track tape player at the time and he had an 8-track tape recorder so he would make me copies of all of these LPs. And, when he put J.D. Crowe and the New South’s ‘Rounder 0044’ album on there in 1975, I just absolutely went crazy. When that album came out, the combination of those five players and J.D. leading that group; it was the most amazing thing I had ever heard. To me, it was perfection in music. I had never heard anyone playing with timing like that, with all of them playing it together. I knew later on when I got older that I needed to learn what they were doing and then find other people to play with who understood it as well.

The self-titled album by J.D. Crowe and the New South has been mentioned in many a conversation over the years when bluegrass artists and fans talk about the genre’s best and most influential albums, and that is still true today. Even though Crowe’s prowess on the five-string appears on many other great recordings, from the sides he cut with Jimmy Martin to the Bluegrass Album Band projects and other award-winning work, ‘Rounder 0044’ will be what he is most remembered for as the years go by. And, rightly so, as that album gave bluegrass music a much-needed, open-minded boost that sparked a whole new generation.

Rounder 0044

Here are some thoughts and insights on the ground-breaking “Rounder 0044” album:

“Rounder 0044 is one of those records that will stand the test of time,” said Skaggs. “I don’t know, it just drove a stake in the ground, as in, ‘This is bluegrass music and we love it, we’re not ashamed of it and we’re going to play it.’ But, I wish I could have been in the band at least six months or a year before we went to the studio to cut that album. When I joined the band, they had already been thinking about doing a new record, yet I still had a lot of material to learn. We played six nights a week and four shows a night, and we didn’t redo songs over the night. We probably played an hour during each of the four shows, and that would include at least be 12 to 14 songs. If you say it was 15 songs or so over the four shows, that is 60 songs a night to learn. We would repeat them the next night, probably, while throwing in some new things. But, I just remember going to J.D.’s house on a Sunday night, the only night we had off, and we started working up new material for Rounder 0044.

“J.D. and Tony were just a cut above,” continues Skaggs. “Jerry was young at the time, but he still impressed the fans out there because he was doing things on the Dobro that even Mike Aldridge hadn’t done, so he was making an incredible impression on people. It was a sound, it was a rhythm, and when J.D. kicked off something, you always knew where the 1-beat was, where the downbeat was going to be. We never had to worry about, ‘Is this where the 1 is, or is it behind or ahead or when is it?’ His timing was so impeccable that when he hit that downbeat, we just all knew where it was because you didn’t rush into it or pull back into it. It was just amazing. What I felt with that group more than any other band I had ever worked in was the timing and the rhythm. Everything felt like it was in the right tempo. Nothing was just flying for the heck of it. Yes, J.D. would play fast tunes like ‘Blackjack’ and ‘Train 45,’ but the timing was still always right there. It was fast, but it never felt like it was pushing you out of the way. It was locked in like a clock.”

Douglas was only supposed to play on a couple of songs on “Rounder 0044,” being the newbie of the group, but once he was there in the studio, he ended up picking on a bunch of cuts. “People call the album by its number and not the actual name of the record,” said Douglas. “That is pretty strange, isn’t it? I don’t think that there are any Alison Krauss albums out there that folks call by its number. Ken Irwin, co-founder of Rounder Records, has told me before that they knew it was going to be a big record, but they didn’t know how big. It was about the fact that this album had all of these people on it, as in just the lineup of the band itself gave it great potential right out of the shoot. Even now, the record still sells, and they are still trying to figure out what the pieces were that made that record so good. To me, it was a new take on traditional bluegrass music, which was closer to the bluegrass core than the newgrass and other stuff being played at the time. We played new material that wasn’t related only to mountains and cabins and food. We recorded a Gordon Lightfoot song on the album, we did a Fats Domino song on it, and it was all cool stuff that J.D. and Tony had back in a hole somewhere and they were just saving it.

“Amazingly, I was only in that band for less than a year, and yet that was when it all just blew up,” continues Douglas. “I went to Japan with the New South and the fans tried to rip our clothes off when we went for our car. We ran to a limo and people were grabbing our shirts and trying to tear them off. It hasn’t happened since, dang it. (laughing) But yeah, it was a strange trip. I wish we would have had a videographer following us, because you couldn’t make this stuff up.”

No Dots?

J.D. was serious about his music, yet he also liked to have a good time. One young man who was lucky enough to see this side of him was Wyatt Rice. Wyatt was 14 years younger than his older brother Tony, yet when Tony played with J.D., he brought his wide-eyed sibling out to spend some time together in Lexington. One day, at a music festival, Tony brought Wyatt up to play onstage with the New South.

“Just like any other of my musician peers and friends, J.D. Crowe was also at the top of my list of major influences,” said Wyatt Rice. “Around 1973 or ’74, before the ‘Rounder 0044’ album and the film they made of the New South came out, we were at a festival and it was either Camp Springs or another one that I can’t remember because I was just a kid of 8 years old at the time. I was hanging out backstage and Tony looked back at me and said, ‘I want you to come up onstage and play ‘Salt Creek.’

“At the time, Tony had two guitars with him and one was his 1949 D-28 that he just had modified. He had binding put on the fret board of this guitar and it didn’t have any markers on it. It didn’t have any dots on the finger board or on the binding. It didn’t have any dots anywhere. So Tony hands me this guitar and says into the microphone, ‘I’m going to get my brother Wyatt up here to play one with us—‘Salt Creek.’ When I went to kick off the tune, for a minute there I got confused because I was an 8 year old kid playing a guitar with no dots on it. So, I flubbed the kick off a little bit until I heard it and realized I had to back down a fret. At the end, as we were walking off stage, I heard J.D. yell out to Tony saying, ‘Why did you give him that guitar with no dots?’ But, he said it in a jokingly way and throughout the years after that, every time J.D. and I would see each other, we’d trade old stories and he’d say, ‘Man, I’ll never forget that time when Tony made you play ‘Salt Creek’ with that guitar with no dots on it.’

Teaching Northerners A Lesson

J.D. was a nice guy, even when he had to teach folks certain musical lessons, which Fleck and Tony Trischka found out one night in Lexington.

“One time, Tony Trischka and I were on a duo tour and we invited ourselves over to J.D.’s house to visit him,” said Fleck. “He invited us in, his hair was perfect, and his banjo was out on the couch. We pulled ours out and he kicked off ‘Shucking the Corn’ at lightning speed. He pretty much trounced us New York banjo players and we were both reeling from how on fire he was. Then, he put the banjo in the case and wouldn’t take it out again after that. Some months later, I remember there was an interview, maybe it was in Banjo Newsletter, where J.D. talked about some of the Northern banjo players and how he was surprised they didn’t know their basics. I could only assume he meant us, and I suppose I agreed. But, at his house that day, he had warmed up—and he was clearly teaching us a lesson.”

Still, just like his hero Earl Scruggs, Crowe paid attention to and appreciated the new sounds being made on the banjo by others.

“I do feel that he had an appreciation for the things people could do on the banjo that he could not,” said Fleck. “I know he loved Bill Keith, and had learned some of his melodic style ideas. But, J.D. chose not to play them, considering them proprietary to Bill.”

Master of Tone

So, what made J.D.’s playing so special, and what was behind his obsession with tone? Jerry Douglas says that “J.D. and Sonny Osborne were the only banjo players that could play slow and sound right.” Douglas speculates, and others agree, that what made that happen was Crowe and Osborne’s love for the guitar and great guitar players. Crowe loved the playing of Ernest Tubb’s guitarist Billy Byrd and Elvis’s guitarist James Burton while Osborne loved the playing of Roy Nichols.

As for Crowe’s tone specifically, Ron Stewart looks at it this way. “The tone mostly comes from the right hand, although the left had has some things to do with it as well,” said Stewart. “But, it is about the right hand. Crowe was a huge tone guy, and that was true of his singing as well, as he loved to sing as much as he loved playing. With both, tone was a big thing. I don’t think he ever quit working on it, to be honest with you, and I think that is why he was so good. The first time that I ever played live with him in a room, I was kind of taken back. When you hear his recordings, it sounds like he is really playing hard, but he’s not. I was like, ‘Oh, OK. I’m going to have to redo my whole approach here.’ I tell banjo players all of the time, when they come up to me after a show and say, ‘Oh my gosh, you seem to be playing so hard,’ and I say, ‘Actually, no, I’m not because I’m playing relatively light.’

“I think it is about how the attack is on and off the strings,” continues Stewart. “Crowe did not play through the strings. I give people the analogy of being whipped with a wet towel back in high school. There is that little flick that you are wanting to do that really stings. You can do just a hard swing with the towel but it doesn’t hurt that bad. But if you perfect that little flip with the wet towel, it really stings, and that is kind of true with the banjo. Crowe was on and off with his notes and didn’t play through them, finding a sweet spot with his right hand.”

Rickey Wasson played with Crowe as lead singer and guitarist for over a decade and a half. For a long time, Wasson has also owned Rick’s Music Shop and Main Street Studio in Clay City, KY. In 2018, Wasson also took over the Meadowgreen Appalachian Music Park venue.

Crowe & Wasson

A few years ago, after Crowe announced his retirement from the road, Wasson decided to do some recordings with him, taking advantage of the fact that Clay City is only an hour away from the legend’s house in Nicholasville. The end result is a fabulous new album called Crowe & Wasson, which can be found at truegrassentertainment.com.

Here are the important facts to know about this album. This project is not a matter of scraping together old studio cuts from the archives and piecing them together to make an album. All of these cuts were recording specifically for this project a few years ago, back when Crowe was still playing great. There is more to the story, however, as there are other recently-discovered cuts recorded in the late 1990s that Crowe insisted be on this new album because of their unique sound.

“My goal with J.D., especially after he retired, was that I wanted to keep him involved in music as long as he could do it,” said Wasson. “Every time that we talked on the phone, which was at least once a week, before we hung up we’d say, ‘Well, we need to do this, we need to do that.’ We always had some place to go, somebody to see, something to do or something to record, or a reason to get together and see each other. So that is how this last album started.”

Crowe had sold a few of his banjos in his later years, and he also made a trade for a special five-string that he had wanted for a long time.

“He called me and said, ‘When are you going to record again?’” said Wasson. “I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He said, ‘Well, I’d like to play this banjo on it.’ I said, ‘Well then, we’ll record next week. I’ll get some guys together and we’ll do it.’ So, I called Ronnie Stewart, Michael Cleveland, and Harold Nixon and then I set up the studio.”

So, on that day back in 2018, the group recorded eight songs right in a row. Then, at the end of the session after Crowe became tired, he handed his banjo to Stewart and asked him to record a couple more tunes so he could hear how his new banjo sounded, and those cuts are on the album as well.

As for the four separate-yet-special cuts on the album, Wasson tells the tale.

“In 1998, I bought a digital recorder and a couple of microphones and I told J.D. to come on up and we’ll practice and play some tunes in my garage and I’ll record it,” said Wasson. “We went in there and played some traditional stuff, trying to learn how to play and phrase together, and it was just the trio of me on guitar, J.D. on banjo and Curt Chapman on bass. I recently found that recording and when we made it, J.D. was about 61 years old and just mashing the banjo, playing the fire out of it. I pulled it out not long ago and played it for him and he said, ‘Wow, we need to put that on this CD. That is the best that my banjo has sounded on a recording. I’d sure like for it to be on this record.’ I said, ‘You’re the boss. Whatever you want, we’ll do it.’”

This new Crowe & Wasson album has been ready for a while, yet it was decided to not release it until Crowe’s life was over as folks would have come out of the woodwork, otherwise, wanting to talk to him about it.

Because of their work together on this recording, Wasson was able to see J.D. nearly up until the end of his life. After J.D.’s last hospital visit, when he was put in the Cardinal Hill rehab facility before going home to hospice care, Wasson took a bunch of the newly printed CDs to Crowe.

“I took a whole box of the CDS there to his room and he was really puny by then, but he was happy to see the copies of the album,” said Wasson. “His wife Sheryl and his kids David and Stacey were there and he was very weak. He could hardly get around, couldn’t walk and was on oxygen. They didn’t have any private rooms at that time at Cardinal Hill, so they told him that they would have to put somebody in the other bed, which J.D. didn’t like at all. Well, they put this young guy in the room with him who had back problems and this good ole boy knew exactly who J.D. Crowe was and loved him and his music. They hit it off real quick.”

After a while, J.D.’s wife Sheryl came up with an idea.

“Hey J.D., why don’t you sign one of these new CD’s and give it to your neighbor over here?’” said Wasson. “She opened it up and J.D. signed that CD, and I signed it as well, and now that is the only signed copy of that CD in the world. This guy may not yet have a clue that he has the only one that J.D. will ever sign.”