Home > Articles > The Archives > J.D. Crowe

J.D. Crowe

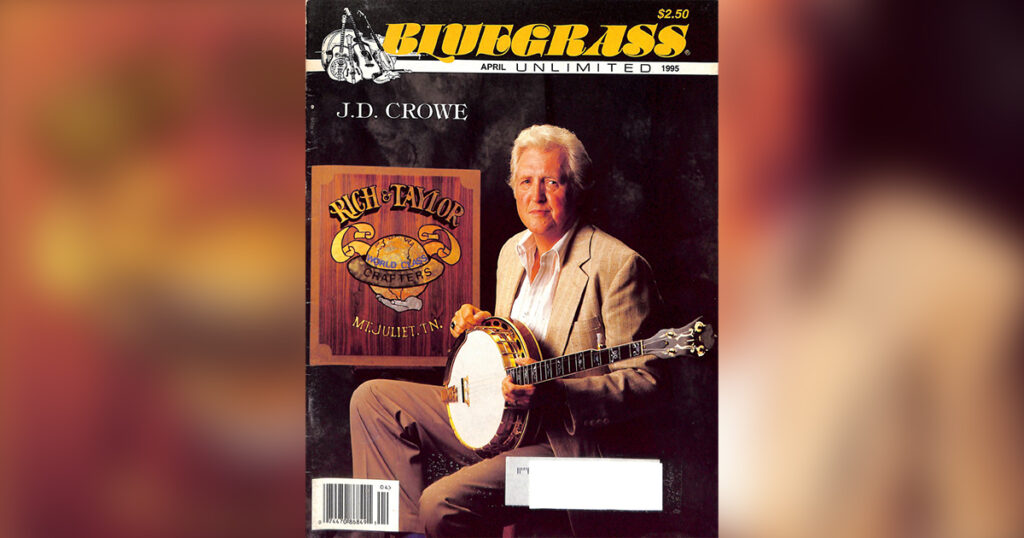

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1995, Volume 29, Number 10

J.D. Crowe has been described as a “musician’s musician” and indeed the subtlety of his playing and his clever innovations are the type of things frequently best appreciated by other musicians. Yet Crowe’s popularity has been far from limited to pickers. The enthusiastic response he has been receiving after ending a brief hiatus from the music clearly shows he is a “fan’s musician” as well.

For more than three decades Crowe has been a true innovator, never afraid to push the boundaries of bluegrass music or to say what he feels. This has sometimes made him controversial, a fact that he readily accepts with the confidence of a man who finds strength in being true to himself.

His banjo style has inspired scores of younger musicians while at the same time attracting new fans to the music. “He plays with a rare combination of precision and soul. He brings a certain dignity to this instrument. He embodies the essential musical attributes in terms of timing, tone, taste, and dynamics” says Mike Munford a Baltimore area banjo picker who occasionally tours with Peter Rowan.

Munford has been playing almost 20 years and has seen Crowe countless times during that span. He says part of Crowe’s appeal is how he manages the difficult task of taking a basically traditional style and making it fresh and new. “It’s traditionally based but with a certain bluesy syncopation. He’ll take a traditionally sounding Scruggs lick and sort of twist the time on it a little bit without destroying it. It’s still essentially the same lick but with a really clever twist to make what sounds like the same old lick have a brand new sound.”

“Crowe has a vocabulary of traditional licks with his own clever rhythmic twists. It’s not mechanical, it’s very soulful and sounds spontaneous. It straddles the border between traditional and contemporary. It’s certainly not melodic or jazzy. He makes the traditional style very interesting to listen to.”

As a youngster growing up in Lexington, Ky., James D. Crowe hadn’t given bluegrass much thought, preferring to listen to country and rhythm & blues. He wasn’t especially interested in the banjo either, having only heard it played clawhammer style, which he didn’t really like. Everything changed at the age of 13 when he happened to see Flatt and Scruggs perform as part of a show. Though he had never heard of them, he was immediately excited by the power of Earl’s playing, and especially by his timing and tone.

He was anxious to learn to play and the next Christmas he received his first banjo, a $39 Kay. As a young student of the instrument he had an advantage over most people trying to learn the instrument—Flatt and Scruggs were playing in town every week.

They had a regular 15 minute radio program on the Kentucky Barn Dance every Saturday night. Lester and Earl were in the studio two hours before show time to rehearse, and the young Crowe was there, taking it all in.

Like many young banjo players, Crowe began by trying to imitate Scruggs. He was listening to other players whose styles he enjoyed, such as Ralph Stanley, but for a time he would stick to his Scruggs-style playing. His first professional experience came with Esco Hankins, a country musician from Knoxville who often played in Lexington. Crowe would appear with him when he played in the area.

While in high school Crowe gained experience with some local bands then spent a summer playing with Curly Parker and Pee Wee Lambert. The following year he did summer gigs with Jimmy Martin and Mac Wiseman. Out of high school, he was hired fulltime by Martin in 1956. He worked with Martin five years, honing his talents and further developing his own unique style. The band toured regularly, and in 1958 became members of the popular Louisiana Hayride radio program.

Crowe tired of the constant strain of touring, playing on the Hayride and recording and left Martin in 1961. He formed a new band, the Kentucky Mountain Boys with brothers Bob and Charlie Joslin. The band didn’t tour, instead working as the house band at Martin’s Place, a tavern in Lexington.

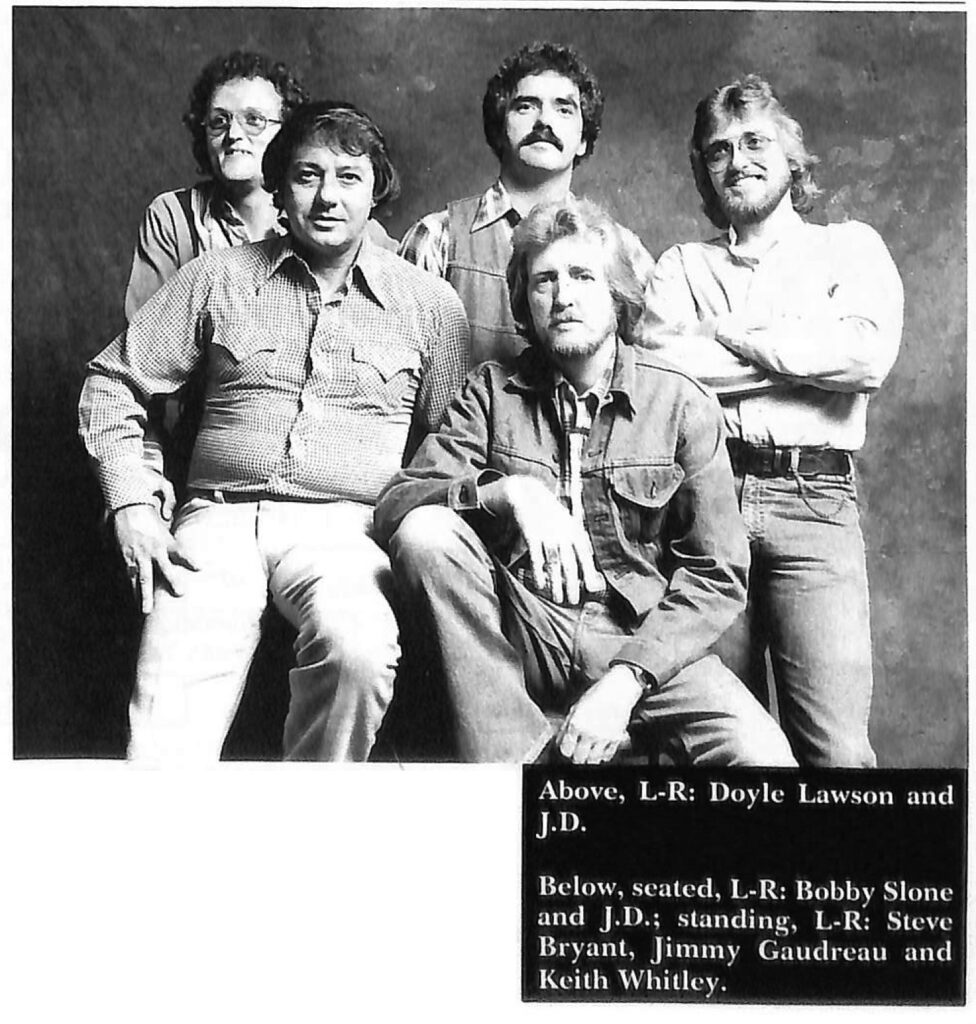

Eventually Red Allen, Doyle Lawson and Bobby Slone would all be members of the band which featured a mix of songs in both traditional and contemporary styles. They recorded three albums for the Lemco label which were later re-released on Rebel. Lawson left in 1971 to join the Country Gentlemen. Tony Rice joined, playing guitar and adding vocals. His brother Larry was already the mandolinist and contributing vocals.

The band’s sound was changing and the members decided they needed a new name to reflect their new directions. The name was carefully chosen. They didn’t want to use the term “mountain” because they fell it would limit the type of music they could do— and what they had in mind was much different than pure traditional bluegrass.

In 1973, now renamed J.D. Crowe and the New South, the band inked a recording contract with Starday Records. Larry Rice left the band the following year, leaving the mandolin spot wide open. Crowe asked Ricky Skaggs to fill in for a few shows. Skaggs sang tenor with Tony Rice taking over the lead vocals. The “handful of shows” turned into almost a full year. It included an album which was one of the most influential bluegrass albums of the decade and perhaps ever, “J.D. Crowe And The New South” released in 1975. The LP also included dobro wizard Jerry Douglas who had recently joined the band. Combining the grit of country with the drive of bluegrass and encompassing elements of traditional and contemporary styles, the album was a masterpiece.

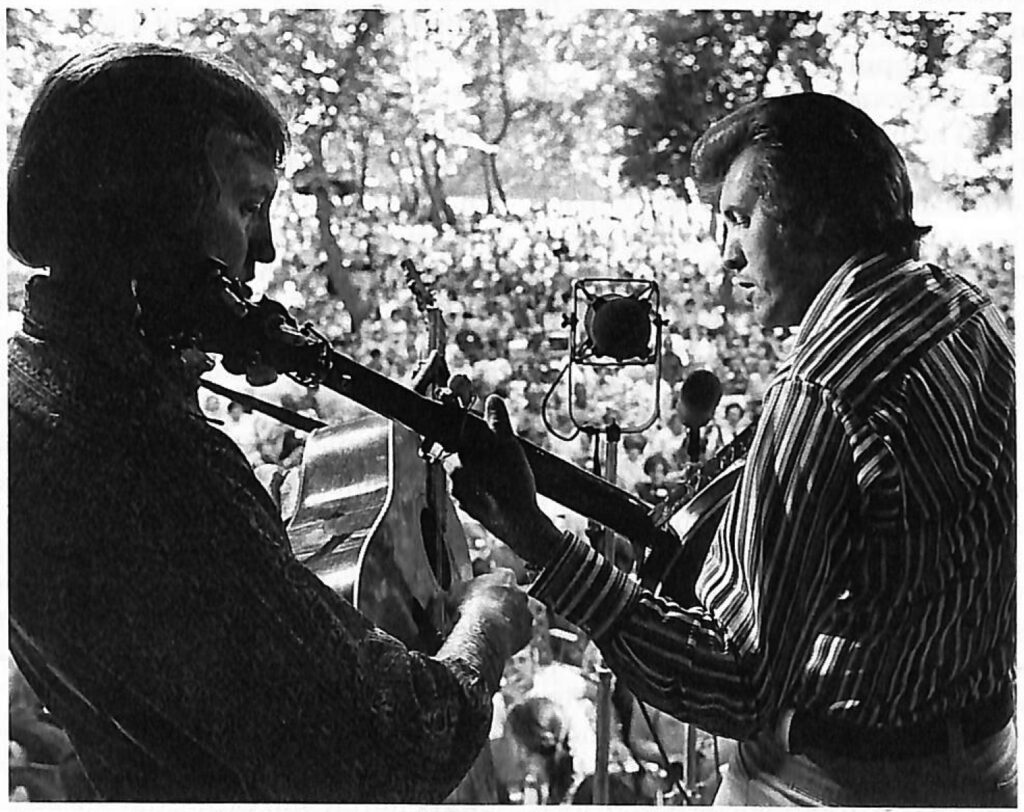

Crowe’s live performances with the New South were as exciting and unique as his work on their recordings. Mike Munford recalls marveling at Crowe’s in-concert performances with various versions of the New South. “During solos it was fascinating the way he would tag out of a break. Take the way he would back up something like ‘Sally Goodin’.’ It would be different every time with all kinds of syncopated hammers and pulls on the third string. It was really interesting, beautiful timing. The precision of his left hand was fascinating to me. He has a certain articulation of his finger work that I found intriguing. It was as much fun to watch as to listen to.”

Skaggs and Douglas left in 1976 to form a new band, Boone Creek. Tony Rice left soon after. These significant departures were the first in many personal changes, each one impacting the band’s sound which smartly didn’t attempt to duplicate the sound of earlier lineups. By 1978 the band included Glenn Lawson on guitar and lead vocals, Jimmy Gaudreau on mandolin and Slone on fiddle. Future country star Keith Whitley joined in 1979. That year the band recorded “Live In Japan” which wasn’t released in the U.S. until 1987. Various sidemen were used on rhythm guitar and electric bass. They also experimented with pedal steel, drums and piano. Crowe found himself the subject of controversy as the band came under attack for the use of these instruments and for electrification.

In 1981 Crowe returned to a fully acoustic sound with the release of the first of six “Bluegrass Album Band Albums.” Comprised of Tony Rice, Doyle Lawson, Bobby Hicks and Todd Phillips in addition to Crowe, the band played a style that was much more traditional than that of the New South, which Crowe continued to front as it went through various personal changes.

By the late 1980s Crowe was again tiring of the rigors of the road. In 1989 he announced he was retiring from leading the New South. “I needed to get out of it when I did. I was tired of it. I got tired of the music, I got tired of the people, I got tired of everything. I had to get away from it and I was fortunate enough to be able to do that.”

For someone in the business for more than three decades, it’s difficult to walk away entirely and Crowe did still occasionally play his banjo in public. There were a handful of guest appearances with Ricky Skaggs’ “Pickin’ Party,” some television work and a few other special events. But there was no touring, and no New South. Mostly he took time to do the things he wanted to do. He devoted more time to his contract mail-hauling business. He could take time off when he wanted and spent time traveling and enjoying taking things a bit easier. “It was enjoyable, the time I had off, I needed it. I always figured I’d probably get back into it eventually after a few years but I wasn’t rushing it. I was taking my time letting things happen. It wasn’t that I had to do it by a certain time. Whatever happened happened.”

What happened was the itch to play regularly grew to the point where Crowe decided to scratch it and once again hit the road. He decided to get together a new version of the New South. The first task was finding the musicians who would carry on the legacy of the many great musicians who had played with the band. Finding a bass player was the easiest part. Curt Chapman had held down that role at the time the band disbanded and he was still available. Chapman and Crowe had remained good friends, often playing golf together. “He said if you ever want to get back into the business let me know” remembers Crowe.

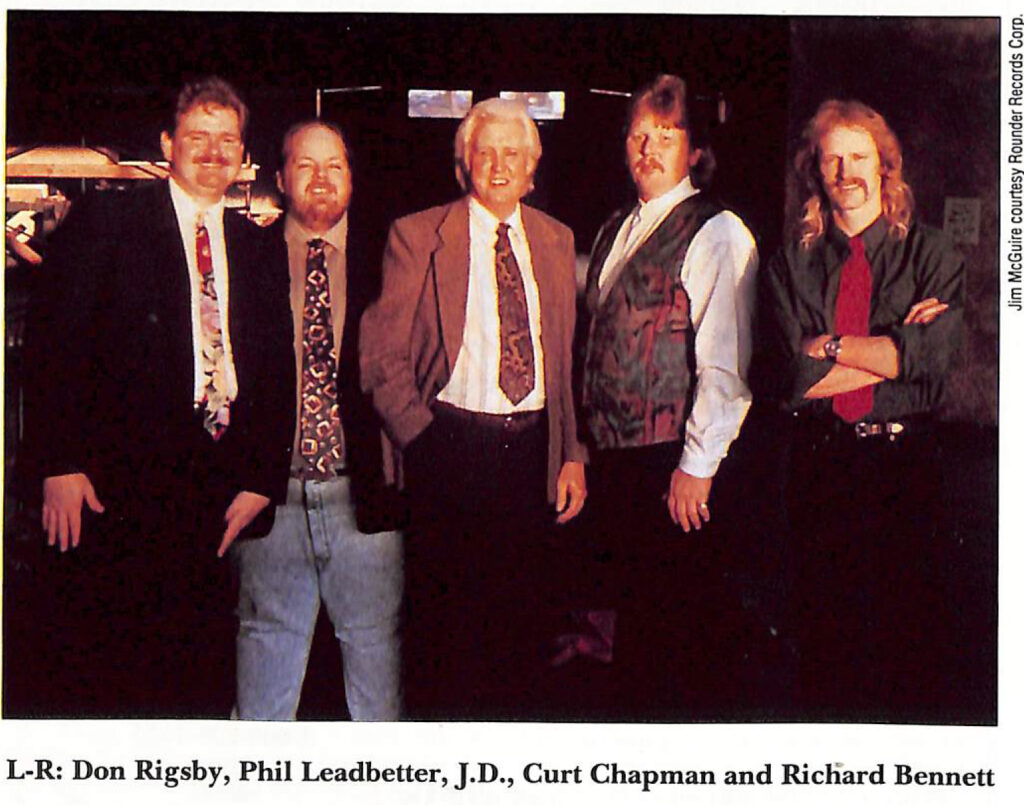

Bobby Slone was now the staff fiddler at Renfro Valley and he recommended a guitar player he had heard there, Richard Bennett. Crowe came to visit him the next time he was at Renfro Valley. “I met him and picked some with him” Crowe remembers. “I told him the situation, what I was thinking about doing and he was very interested. He had just finished a job at Dollywood and wasn’t really working anywhere at the time.” Bennett has moved on to join Lou Reid, Terry Baucom and Carolina and long-time bluegrass multi-instrumentalist Greg Luck has replaced Bennett as of early 1995. Former Bluegrass Cardinal Don Rigsby was added on mandolin, Phil Ledbetter on dobro and Randy Howard on fiddle.

The band began touring, playing a number of shows and festivals. Everywhere he went the fans were glad to have him back. And Crowe was enjoying being back, especially the chance to see some old friends. “One thing I had missed was getting together with all my friends after the shows, all the pickers I’ve known through the years. I missed that as much as anything.” He was recognized by the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) when he was named in 1994 as Banjo Player Of The Year, even though he hadn’t put out a new record in eight years.

Actually the band had finished an album, “Flashback,” which was released not long after the September IBMA conference. “If you’re going to get back in the business and you want to be more than a nostalgia act you have to record,” says Crowe. “You can’t live on past things—its time to move on.” The release, entitled “Flashback” has been more successful than anyone could have hoped for. The National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences saluted the album by nominating it for a “Grammy” for “Best Bluegrass Album.” Crowe was honored by the nomination which he says he didn’t expect. “It’s great just to be nominated for it—it’s a narrow door to enter. I didn’t set out to try and get a nomination, that was the farthest thing from my mind. The only thing I ever strive to do is to make a good album.

“A lot of people say it sounds a lot like the old ’75 band. It does remind you of it in spots. That’s good, I can’t think of any group any better.” Any similarity between the sound of the two bands was coincidental according to Crowe. “It just worked that way. I wasn’t trying to find that sound because it’s virtually impossible to reproduce that.” Indeed the album actually sounds more like a cross between the 1975 band and the more traditional sounds of the Bluegrass Album Band.

After a few years off Crowe is searching for his place in the current bluegrass scene. One thing is for sure, he wants to continue to do something fresh and new even as the fans clamor to hear their old favorites. “Audiences want to hear you do just what you did 20 years ago. I can’t do that and I don’t want to. It’s okay to a point. There are things you’ve expected to do through the years and that’s fine and we do that, but you also have to go on and do something new. How can you be an innovator if you don’t do something different.”

Despite his now legendary status Crowe continues to merge his playing into the total band concept, resisting any urges he may feel to hog more of the spotlight. “I do what I feel, what fits the songs and compliment what’s going on in front of me. A band has to blend, with the musicians complementing each other. There can’t be someone up on stage who’s trying to outshine the others.”

This ability to fit his sound into what the other members of the band are doing has always been at the heart of Crowe’s playing. Munford emphasizes, “He’s such a great ‘band’ banjo player. He doesn’t try to make the banjo the feature instrument, he knows how to work it behind the vocal, how to backup the fiddle, what to do behind the mandolin, when to come in strong between the lines of a tune.

“One thing that’s a trademark of his is that during a trio when he would come in behind to sing the banjo would drop off with a couple of powerful tags then the vocals would come in strong. When there was a pause between the lines of the vocals he’d come in with a couple of really beautiful tag licks, just in the right place, just with the right time and tone. It’s a great sound that’s really unique to him.”

“You have to realize what not to play and when to play” says Crowe. “There are so many pickers out there, and they’re good pickers, but they haven’t realized that you don’t have to play everything you know in one song or one break. They’ve never been in a band concept, they’ve always been an individual player. They’ve played in jam sessions or they’ve set in with bands and they try to play more than they really should. If they want to have a good band sound they can’t do that, they have to settle back and blend it. That’s the way any good solid band works.”

Crowe is hesitant to talk about young banjo players he likes because he thinks there are many and doesn’t want to slight anyone. But two names that came immediately to his mind were former Doyle Lawson sideman and now Bass Mountain Boy Jim Mills and Robbie McCoury. He calls McCoury “a good young picker, very enthused and he plays good solid banjo.

“That’s the thing you’re now hearing more of—the solidness, the separation, playing in a band concept instead of just getting out there and playing like you’re in a contest. There’s not a whole lot of them but there’s a few.” It is this ability to blend into a band concept that has always been one of Crowe’s strengths according to Munford. “It’s not just a banjo blasting from one end of the song to the other, it goes through various dynamic volume changes that make the music much more exciting.” Crowe estimates the band played between 60-80 dates last year. He says he’d like to do more shows, but seems unsure just how many. “I would really like to do a little more and probably this year we will. But I don’t want to do a whole lot because I’m not as young as I used to be. I kinda like being around my house a little more.” But he has trouble sticking to the idea of doing only a “little more,” saying he told his booking agency “If it’s good—book it and let me know just where it is. We could work 100 days, we could work 200 days, it wouldn’t matter to me.”

He is busy planning the band’s next album as well, and hopes to be back in the recording studio within a few months. Talking with J.D. Crowe you get the sense that this is a man happy with what he’s doing and looking forward to the future. He’s someone who will never be content to merely rest on his laurels, but will continue to be an innovator and create new and exciting music. He seems fresh and rejuvenated by his time off and ready to be one of the leaders taking bluegrass into the 21st century. For J.D. Crowe and for bluegrass fans, the best may still lie ahead.