Home > Articles > The Tradition > IBMA Hall of Famers Revisited

IBMA Hall of Famers Revisited

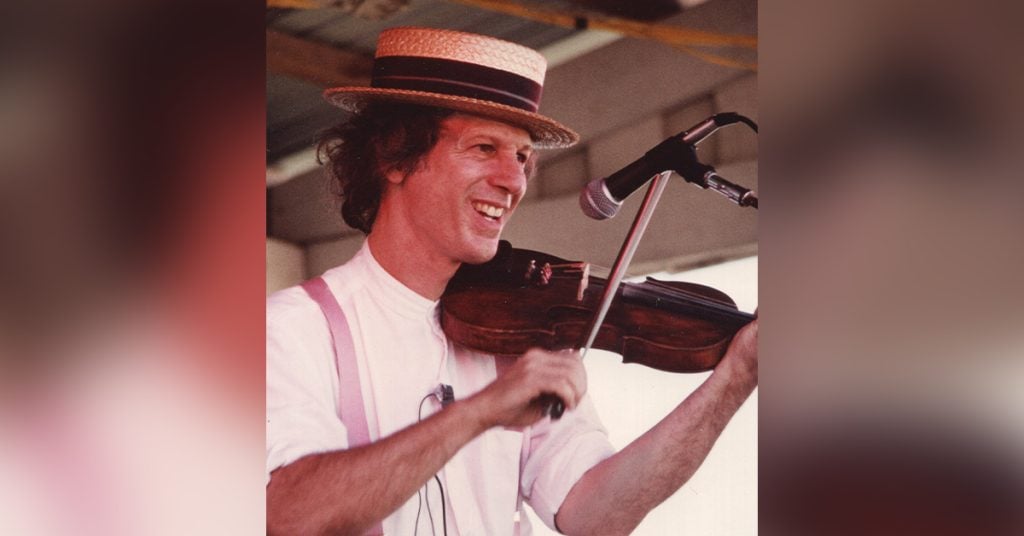

John Hartford

Photo By Barrett S. Bacau

It is a Monday afternoon in December of 2020 and the DJ on the excellent WNCW-FM radio station is in the middle of diverse set of music. One of the best listener-supported radio stations in the U.S., WNCW can be heard beaming from radio towers located throughout the mountain and foothills region of western North Carolina from Spindale to Boone, from Asheville to Charlotte. DJ Eddie B. Stokes, who is substituting for regular host Roland Dierauf that day, brings up the 2021 Grammy Award nomination for the album The John Hartford Fiddle Tune Project, Vol. 1.

It is a new recording that features an all-star cast of great roots musicians bringing to life some long-lost fiddle tunes that Hartford wrote yet never performed. It is then that the Stokes talks about Hartford’s influence on this acclaimed radio station 20 years after his death in 2001, saying, “John Hartford was a quirky artist that we love here at WNCW. His music is a guidepost for what we do here at the radio station on a daily basis.”

John Hartford was a legendary musician and stage entertainer, yet he was also a bit of a character offstage as well. Right after his death on June 4, 2001, the message book on his website was soon filled up with 2,000-plus stories describing encounters with Hartford that left an impression on people through the years. Many talked about a memorable concert by Hartford, including one night at the Skyline Music Festival in Ronceverte, WV, where Hartford asked the crowd to bring lanterns to the stage so he could do a show after a barn fire destroyed all of the electric generators.

Others were simply fishing on the banks of the Cumberland River when Hartford walked up, out of the blue, hoping to see a riverboat go by. Hartford was a licensed riverboat pilot and the old ships of our waterways forever intrigued him. Before he left those surprised anglers, he left them an odd tip saying that if you take two slices of white bread and cover them with good mayonnaise and then add regular Doritos in-between, it will taste like a ‘Poor Man’s BLT.’

There are still John Hartford stories to be found and in this article, we will unveil two new ones that I recorded for Bluegrass Unlimited in late 2020.

First, however, we will bring an important part of Hartford’s story to life using the immediacy of newspaper articles from the late 1960s and early 1970s. What I found is fascinating, a glimpse into an artist trying to deal with new-found fame.

Newspaper articles are bits of real-time history captured in the moment. Hartford made the papers often during that era because he was coming off of his TV show star period, achieving fame on national television programs such as the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour. He also gained notoriety for writing the hit song “Gentle On My Mind,” made popular by Campbell and recorded by over 200 other artists. It became one of the most played songs in the history of radio.

That brings us to a fascinating period between Hartford’s work on TV and his move to being a full-time musician. The in-the-moment information about Hartford’s life excerpted below gives new insight into his career and the choices he had to make during this crossroads of his life.

For instance, in the September 24, 1970 edition of the Orlando Evening Star, Hartford is quoted in the “Youth Beat” section by Roger Doughty of the Newspaper Enterprise Association. Apparently, Hartford has been tapped to do a syndicated TV show about ESP and the paranormal.

“I believe that everything that happens has happened before,” says Hartford. “That is why I don’t think I have ever written a song, as the song was there all along. I just discovered it and brought it into the present time.”

After mentioning “Gentle On My Mind,” Doughty breaks the news, “John has a syndicated TV show called Something Else that will popping up all over the country, in 80 cities so far, and it is well worth looking for.”

After doing more research on the TV show Something Else, I discovered that it ran for 34 episodes on syndicated TV networks in late 1970 and early 1971. It seems to have turned into a mostly music show by the time it aired. The first 22 episodes were hosted by comedian John Byner. Hartford appeared on the opening episode as a performer along with Three Dog Night, Jimmy Webb and a band called Mephisopheles, who played their song ‘Listen To The Crickets.’”

Beginning with Episode 23, Hartford took over the hosting duties for the show for 12 episodes. Some of Hartford’s more notable musical guests included B.B. King, Conway Twitty, Jerry Butler, The Illinois Speed Press, Flaming Ember, Essra Mohawk, Johnny Mathis, Iron Butterfly, Canned Heat, Dr. John the Night Tripper, Steppenwolf, Hartford’s friend Earl Scruggs, and Harford’s band Iron Mountain Depot.

There was also talk at that time of Hartford being considered for a TV detective series role after he left the Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour. If those opportunities had taken off for him, would Hartford have morphed into the full-time musician that recorded the landmark album Aereo-Plain in 1971?

As a side note, the old clips of Hartford lip-synching to his old songs in highly-produced videos that are still floating around on Youtube are from the Something Else show.

Just how famous was John Hartford in 1970? On the dramatic front page section of the News and Observer newspaper published in Raleigh, NC on April 14, 1970, there is a headline that reads, “Apollo 13 Astronauts In Trouble.” Below that, there are two Soviet Union-based headlines reading “Red Nuclear Sub May Have Sunk” and “Brezhnev Lectures Workers.” Then, below the fold is the headline, “Man Said Posing As Songwriter.”

“A 33-year old man was arrested by Raleigh Police on charges of false pretense after a woman here accused him of borrowing $900 from her while posing as John Hartford, songwriter for Glen Campbell,” said the article, about the defendant William Russell Hagy. “Mrs. Nora Johnson Proctor of 409 Stiller Street signed the false pretense warrant against Hagy. The investigating detective Stephenson also said that Hagy, using the name John Hartford, had spoken to students at local high schools during the past several months. Another Raleigh detective said that Hagy told him on Monday night that he was ‘in show business’ and that he uses the name John Hartford, contending that he was with Glen Campbell for about a year and had written the popular song ‘Gentle On My Mind.’”

Amazingly, the victim, Mrs. Proctor, knew a girl named Andrea Smith who was actually married to Hagy. Smith, in on the scam, introduced her husband to the Proctor’s as ‘John Hartford, the banjo player.’ The Proctors were a thinking couple, however, and started to see through the cracks.

“Several times during Hagy’s visit to the Proctor home, she tried to get him to play the banjo but he always declined,” continues the article. “‘We could never get him to sing until he went to our church,’ said Proctor. ‘He tried to sing ‘Gentle On My Mind’ but he didn’t know the words, and he was supposed to have written the song.’”

While at Myrtle Beach, SC the Proctors saw John Hartford on the Lennon Sisters TV show and noticed that Hartford was not much taller than the Lennon Sisters. Hagy, the imposter, weighed about 225 pounds and was six feet, four inches tall and that was another part of his undoing.

To add another layer to the story, the Proctor’s teenage son Paul Proctor was at the high school when the imposter Hagy spoke while impersonating Hartford, lecturing the students on how he became a good songwriter, talking about the breaks he had in show business and about how Glen Campbell was “a good old country boy.”

By 1971, the articles on Hartford began to change. Soon, he is specifically touting ‘bluegrass music’ instead of the country and folk music terms used in previous articles as he settles into the second act of his music career.

Free from the limitations of being on a high-powered record label such as RCA Victor, Hartford began to do his own thing on his albums. His first post-Hollywood band is the aforementioned Iron Mountain Depot. Then, in a Detroit Free Press article published on July 30, 1971, his band is mentioned, yet sadly their names are left out of the piece. But, as you read it closely, it is obvious that he is touring with the Dobrolic Plectoral Society group that recorded the Aereo-Plain album.

“The disciplined moody musician who sat in the back row and wrote ‘Gentle On My Mind’ went underground and has surfaced in of all places, bluegrass country music,” said the article. “He has surrounded himself with three string (musicians) so country that two of them still have straight hair cuts. One plays a steel guitar (Tut Taylor on resonator guitar), one does rhythm on acoustical guitar (Norman Blake), and the third plays fiddle (Vassar Clements). With their shirt-tails flapping and looking like a quartet of comic strip moonshiners, the Hartford Quartet plays and sings about the ‘Banks of the O-Hi-O.’”

In an article written on May 29, 1973, in the Tampa Bay Times, the Aereo-Plain Quartet has broken up and Hartford is touring with Norman Blake and a singer named Doris Abraham, whose career has yet to appear in our research. With Hartford’s life as a TV star now in the rear view window, he reflects on what made it all come to an end in this piece.

“Politics, mostly,” said Hartford, in the article. “When the Smothers Brothers Summer show became the Glen Campbell show, my allegiances were with the Smothers Brothers. The Campbell people didn’t include me in their plans. Glen Campbell is making more money, but he doesn’t get to play as much. I want to play. I don’t have a manager anymore, just an agent. I do all of my own managing. It’s freer that way. I enjoy the college audiences as they respond, they understand. I’m going to keep touring until I get all the old show business out of my blood. When I get a bit older (34 at the time), maybe I’ll knock off some of the performing and do more drawing and painting. It’s hard to say what happened to my head after I left television. I changed, and it was tough for a while, but those things are all straightened out now.”

In other articles from this time period, Hartford talks about not wanting his hit song “Gentle On My Mind” to be used in TV commercials and he also did not allow it to be recorded as a parody. In an interview with the Associated Press, he rebels against the notion of stardom. At one point, he knew that star trip phenomenon was happening when somebody asked him for an autograph while he was at Westminster Abby in the UK.

“People are always asking me, ‘How does it feel to be a star?’” said Hartford, in 1969. “I don’t like the word. I’m not into the whole entertainment business game. All I am is a carcass with a banjo attached and words coming out of the top. I’m just the communication device.”

In that same article, there is this reference; “Hartford carries paper around in his shirt pocket and often jots down ideas for lyrics.” He would do this, mostly using 3×5 cards, for the rest of his life.

Recently, multi-instrumentalist Tristan Scroggins was asked to work with the Hartford Family on various projects. Number one, he appears on the John Hartford Fiddle Tune Project, Vol. 1 album that was nominated for a 2021 Grammy Award. Secondly, he was hired by the Hartford Family to scan in all of the 3×5 cards that John Hartford used and saved over the years.

As a result of this amazing access to Hartford’s inner-most thoughts, impromptu ideas, drawings and messages that were jotted down on these cards, Scroggins has had a unique view into the mind of this acclaimed artist and musician.

Bluegrass Unlimited talked with Scroggins in December of 2020 about working with the Hartford Estate.

“John Hartford’s daughter Katie was looking for someone to help scan in those 3X5 cards as they have been going through his stuff for the last 15 years,” says Scroggins. “John had a ton of things left behind after he died in 2001, but they are almost done going through it all. They have also donated a ton of his stuff to various, appropriate museums, archives and collections. I know they sent some things to a steamboat museum in St. Louis, I believe. They also donated a lot of stuff to the Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro and to the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville.”

As for Hartford’s infamous 3×5 cards, they found them in an already-organized way as Hartford has his own system of storing them.

“My guess is that there were about 20,000 of those 3×5 cards,” says Scroggins. “It is truly an insane amount. He had a filing cabinet full of them and he would carry about two dozen of them around at any given time. He would then come home and file the used cards away in a certain order.”

As for what was found on all of those index cards; the content ranged from everyday subject matter to new tunes written down for posterity.

“Some of the stuff is more mundane, like shopping lists and what to pack for the airport and things like that, but he would also write down tune ideas and song ideas,” says Scroggins.

“While going through all of them, you can see that he would write down almost every idea that he had and put some work into all of them. There are definitely a lot of songs that he finished just for the fun of it on the cards. He either liked the tunes, didn’t like them or just didn’t want to perform them. Plus, there is a lot of research on them as well, where he would try to connect the dots with old-time tunes that had different names. And, there were a few I found where he was clearly pretty sick when he wrote them as he used the cards to communicate when he was too tired to talk. There are a lot of funny things on them as well, and a lot of random stuff, like Kenny Baker’s hot toddy recipe.”

It is almost two decades since Hartford’s passing in June 2001, yet out of the blue, new stories still emerge. In November 2020, I was asked to do some interviews with the cast of Bridging The Gap, a live on-stage music documentary being filmed about the evolution of Appalachian roots music. Produced by the essential Junior Appalachian Musicians program, that teaches bluegrass and old-time music to young people in four states, the film should be out later in 2021.

One of the artists I interviewed that day was musician Jim Costa. Without John Hartford being mentioned in any way, Costa brings him up on his own and this leads to new Hartford stories.

Costa is not only a wonderful old-time musician; he is also one who studies the old ways of doing things by the master craftsmen of centuries past.

“I knew John Hartford and he asked me one time, ‘Why didn’t you become a professional musician?’ I said, ‘John, I’d like to, but I have too many other hands-on interests like collecting antiques and restoring and fixing things,’” says Costa. “I have made a museum in my backyard in Talcott, West Virginia, and at my house, I have recreated an 18th century woodworking shop and a blacksmith shop filled with hundreds of old items that were made in those kinds of shops. Since I was a kid of 13 years old, I have collected old agriculture implements and anything to do with hearth cooking, and I dismantled an old country store that had everything in it from stone mason tools to the old pick and shovel miner’s tools and even their clothing.”

Hartford was also into a lot of those same old-timey things going back to his love of steamboats, so it makes sense that he and Costa would become friends.

“I got to spend a week with John Hartford and I will never forget it,” says Costa. “I had met John at various music festivals over the years and he loved Uncle Dave Macon’s music as I did. I used to play at the Museum of Appalachia in Tennessee and when I met him there, John said, ‘I’d like for you to come down and spend some time with me and we will go down and around some of Uncle Dave’s old haunts.’ I had met some of the Macon family earlier as I was very interested in Uncle Dave’s style and how he played music, his instruments and his whole history in show business.”

As fate would have it, Costa and Hartford also found common ground with steamboats.

“I had a great grandfather that was involved in building three steamboats,” says Costa. “They were work boats, more like a tug boat. I had a photograph of one of the boats, which John loved because he was a licensed boat pilot. John told me to bring all the information I had about the boat that my great grandfather worked on and he would nail it down. All I had was a name of the boat and an old tintype photograph of it. When I got to John’s house that day, he had a library and books on the first shelf off of the floor that included a nautical registry of all of the boats that had ever been made in America. And, we found that boat, which was built in 1883. I still have a sketch that John drew of that boat’s engine, which he made as soon as I showed him the tintype. He knew what engine was inside of it, even though you could not see the engine in the old photograph. We even looked up the boat’s demise as it was caught up in a big ice flow during one cold winter.”

As soon as they were done looking up old steamboats, Hartford and Costa turned to playing music together.

“John was going to have a house party and invite Earl Scruggs, Grandpa Jones and Leroy Troy,” says Costa. “I’ll never forget it because there was the threat of a tornado that night and the phone rang and it was Grandpa Jones on the other end, saying, ‘Well, I was going to come out but there is a tornado out there and we are afraid to get on the road, you know.’ So, he didn’t show up and neither did Earl. But Roy Huskey Jr. came by with his bass and we played some music in John’s living room. What was cool about it was that Roy had his father’s old bass that had accompanied Uncle Dave Macon on the Grand Ole Opry back in the day.”

All of these years later, Costa has his own museum piece featuring John Hartford that he treasures.

“I have a recording of him talking about his technique,” says Costa. “He got into this thing about the longbow style of playing, and I had a little tape recorder with me and I said, ‘Do you mind or care if I record this?’ He said, ‘No.’On the recording, he is explaining how the bow is reacting with the left hand and how the rhythm happens, and you can hear the difference as he plays different styles. It was really interesting. And, because John loved the music of fiddler Ed Haley, he loved all of my old West Virginia ‘graveyard’ or ‘spooky tunes’ like ‘Yew Piney Mountain’ that are played in the old archaic fiddle tunings. He was quite an artist and a true talent. John was a hoot.”