IBMA 2024

Musicians and Community Support One Another

Photos by Ricky Davis

2024 was preordained to be a bittersweet IBMA year, like a high school graduation, throwing caps in the air, fully realizing that the World of Bluegrass landscape as we knew it was about to change. After 12 years in Raleigh—a period long enough to be a lifetime for young musicians—the time for transition to Chattanooga was on the immediate horizon. Optimism ran strong that a new bluegrass playground would be replete with bells and whistles, rather like boarding a newly christened cruise ship after a multi-year vacation run on a favorite vessel. But bluegrassers never anticipated IBMA moving to another holler would be wedged out of the primary circle of concern by something much more significant and life-changing: a hurricane impacting many of the musicians and constituency.

Helene blew in the back door like an uninvited guest at a dinner party when the table was set. Many attendees were already in place, having arrived in time for the three-day industry professionals’ conference that preceded the two-day World of Bluegrass festival. Agile IBMA officials scurried to make last minute adjustments to the schedule, planning around rainfall, canceling Friday’s daytime street stage shows until 5pm. Some attendees spent Friday morning holed up in hotel rooms or at the North Carolina State Fairgrounds campground, tuned into WRAL-TV coverage, keeping a close eye on tornado warnings and storm drains. Others in the lobby and hallways of the Marriott never put down their instruments, like the Titanic’s orchestra playing “Nearer My God to Thee.”

Balsam Range, from Haywood County, was one of the bands scheduled to play Friday evening that had to cancel because travel wasn’t possible. But by Saturday the sun was out in Raleigh and the festival became a temporary bubble of bluegrass oblivion before the reality of damage reports came rolling in.

Awards Show

On Thursday evening, light drizzle was just making itself known in Raleigh through an elevated frizz-factor, threatening to wreak havoc with the fancy hair-dos of musicians dressed in their blueclassiest for the Awards Show. Stage curtains were draped like old Hollywood as fans found themselves rubbing elbows with the bluegrass elite.

Hosted by John Cowan and Missy Raines—both bassists—the 38th annual award show featured plenty of bass notes. “It’s the age-old debate and it threatens to tear our world apart,” Raines said with all seriousness. “Upright or electric bass?” After taking sides like bass-clef-boxers in the ring, Cowan diplomatically declared a theme that would be repeated throughout the week, “Music has a way of bridging differences.”

When accepting the Male Vocalist of the Yearaward, Danny Paisley said, “I just sing from the heart and I’m deeply touched that other people like what I do,” adding a nod to another nominee in the category with, “Del McCoury and my father were my two greatest heroes.”

When introducing the Bass Player of the Year award, Raines commented (and even those who have just been in the vicinity of a bluegrass bass musician understand it well) “Bass players do more than get us to the 1 and 5 and back again.” Upon accepting her award, Vickie Vaughn said, “Thank you for being supportive of a genre that’s going to live forever.”

Authentic Unlimited took an award for Video of the Year—the first year for the category—and there was a tie. Upon acceptance, Stephen Burwell teased the audience: “Thank you so much—we spent a lot of time doing our hair for that video.”

When presenting the Fiddle Player of the Year award, Laurie Lewis said, “We fiddle players might say we provide the best color commentary of the band.” The award went to Deanie Richardson.

Later when the group also was awarded Vocal Group of the Year, banjo player Eli Johnston said, “This is the culmination of a bunch of buddies doing hard work together.”

When the Del McCoury Band was awarded Entertainer of the Year, shouts of “Del Yeah!” rang out in the audience.

In his acceptance speech for Hall of Fame induction, Jerry Douglas said, “I want to thank IBMA for spreading the good word of bluegrass music,” adding, “you don’t get here alone.”

An IBMA member who had worked a booth on the Expo floor all day talked about how heavy his eyelids got during the show—just because it had been a long day, not because the event was boring—and said he planned to sneak out “during the next standing ovation.” It was a story that told a story: the auditorium was full of enthusiastic fans and fellow musicians who were both happy and exhausted in perhaps equal measure.

Highlights

Conference attendees know they cannot physically attend all the sessions and shows, so the takeaway experience ends up being individualized. After elbowing past the dual elephants in the room (the move from Raleigh and the hurricane) some themes rose to the top.

Black Music in Appalachia

In a session on Black Music in Appalachia, Lee Bidgood, East Tennessee State University Appalachian Studies professor and moderator challenged myths of isolation and frozen time, asserting “there’s more in the holler than Scotch-Irish.”

Appropriately enough, the “Tennessee Ukulele Lady,” Kelle Jolly opened up the session by singing, “I’m gonna sit at the welcome table.”

Panelist Dr. Dena Jennings said, “I come from 7 generations of Black folks living in a holler in Kentucky. You sing a song from your culture, I’ll sing a song from my culture. We’ll probably find more things alike than different.”

Bidgood said, “Putting boxes around genres can limit our joy of the music.”

When asked how they avoid being “tokenized,” Jolly said, “I don’t know how to do that and make money. I feel like I need to be there.”

Trey Wellington (panelist) said that we think of it as just a problem in the American south, but that he played in 30 states this year and in each of these states there was at least one venue where he felt like he was there to fill their quota for a black performer.

Wellington said he grew up in Ashe county, around creative energy. Speaking of his Black Banjo project, he said, “I’m going to do what I want. As Black creatives, we should be able to put our voice and feelings into it and stories behind it.”

The Voice as an Instrument

Hosted by Dede Wyland, Stephen Mougin, and Dan Boner, the session focused on the importance of vocal education. The panelists asserted that the voice is the least studied instrument in bluegrass music and one of the most central. Traditionally the mindset was to study technique in stringed instruments and “sing if you can” as something of an afterthought. Studying voice and learning technique is not going to turn you into a classical performer or hurt your bluegrass sound, the experts assured. “Learning how to breathe and relax muscles will bridge the gap between what you feel and what you are able to express.”

Boner explained that he grew up in a Free Will Baptist church and was playing and singing at age 7. He remembers someone in the congregation seeing him perform saying he was cute. He almost quit playing because of it. “Bluegrass isn’t cute—we’re serious about our music,” he said.

Mougin said he grew up in western Massachusetts, “the epicenter of bluegrass.” He said, “If you’re a singer, you feel good about 1% of the time.”

When Boner saw Larry Sparks practicing vocals backstage at a show and marveled, thinking that at his level he would no longer need to, Sparks told him, “You never get too old or too good to practice.”

On finding your own style, Boner said, “It’s okay if you emulate styles when you’re searching for yours. But move on to a different singer and a different singer. You end up with an accumulation, and out of that your own sound evolves.”

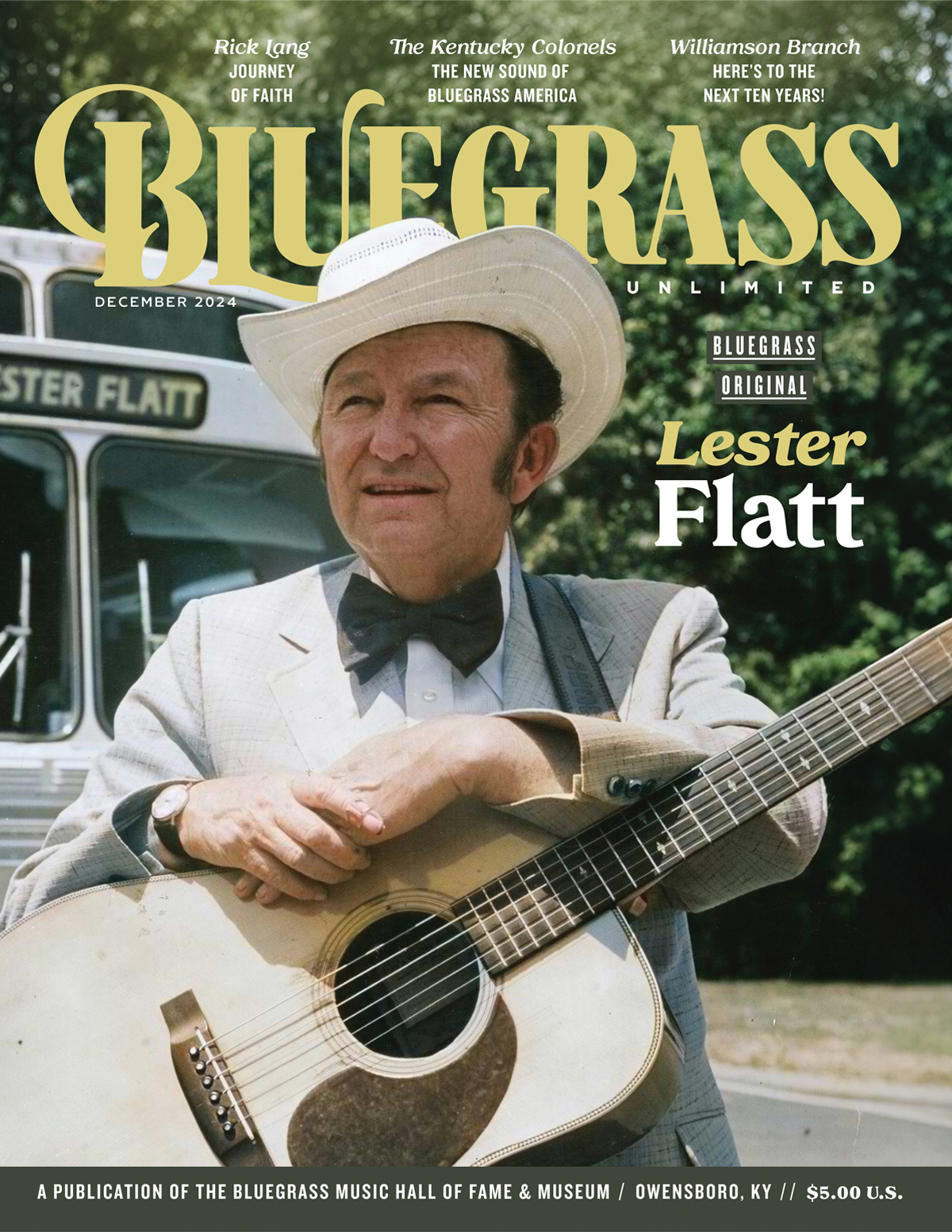

Mougin said he had a professor say, “If you steal from one person, it’s plagiarism. If you steal from everyone, it’s research.” “My two favorite singers are Lester Flatt and Frank Sinatra,” Mougin said, “they were determined to tell a story.”

The panelists attempted to answer the big question, “What makes a voice sound like a bluegrass singer?” It’s not just that “high lonesome sound,” they said. It’s “phrasing, timing, and distinctive ornamentation.”

Writing Bluegrass Gospel

In a workshop on writing bluegrass gospel, presenters reiterated the timeless advice, “Write what you know.” “I made a career out of writing songs about things I can relate to,” Daryl Mosely said. “I just sit down to write something honest. A lot of my writing is about real living, messing up. Honesty sells,” panelist Donna Ulisse said.

“The gospel is the lens from which we view the world,” Kristen Leigh Bearfield said, explaining the distinction of writing “gospel” music. “Tell your story and let faith be a part of it. Whatever’s going on in your real life, right before you write, don’t tune that out.”

“There may be great-grandchildren that I never get to know. And the only thing left of me will be my songs. Be mindful that your songs represent you,” Moseley said.

“Ideas come in the strangest ways,” Ulisse said. “You have to get naked to write. Not literally but you have to peel off layers. I don’t know about coal-mining, but I know about heartache.”

Union Grove Stage

A distinction for 2024 was the inclusion of a “Union Grove Stage” with a competition open to anyone present as a tribute to the 100 year anniversary of the Union Grove Old Time Fiddler’s Convention founded by H.P. Van Hoy. The stage and contest were sponsored by the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

The convention was all about “sharing the music from person to person,” the host said, and the Union Grove Stage’s purpose was to carry on and honor the tradition. Contestants were allowed to have an accompanist and were told to play for five minutes, a fast song and a slow song. Age categories ranged from 15 and under to 65 and above. There were categories for old time fiddle, bluegrass fiddle, old time banjo, bluegrass banjo, mandolin, and guitar. Fiddler Earl White was announced the grand prize winner.

Showcases

Possibly one of the best discoveries for attendees at IBMA is the showcase, an opportunity to see bands familiar and new, close up in typically a small space. Every nook and cranny of the Marriott hotel downtown was hopping with music for several days and nights.

Introducing his mandolin player, Mark Stoffel, Chris Jones said he is from “very eastern North Carolina…Germany.” The Night Driver musician went on to play a song not often heard in bluegrass circles: “In the Mood” by Glenn Miller.

“Our first time at IBMA was in 2015 and we were on the youth stage. Hair was a lot shorter,” Benjamin Luckhaupt of My Brother’s Keeper said, playing in the Robust Records showcase. “There was a hurricane that year too.”

Exhibit Hall

It would be safe to say that an attendee could have stayed all day in the Convention Center at the Exhibit Hall and not been bored. In recent years more and more showcases were added to vendor booths, making a stroll through the aisles a treasure hunt of music, sometimes with multiple bands playing at the same time. To get to the Exhibit Hall required walking by the International Stage, and it was a popular gathering place to hear new music.

Finale

Another band impacted by the hurricane and unable to attend for their headliner slot Saturday night was the Steep Canyon Rangers, from Asheville. Sierra Hull’s band played before the final act of the night at the Red Hat Amphitheater.

Before playing, “Beautifully out of Place,” Hull greeted the audience with, “We’re so stoked to be here….it’s always like a homecoming to come here.”

“I started playing mandolin at eight years old but came to my first IBMA at nine years old and it was being a part of this community that made me stay,” Hull said. “What I like about festivals is we can all come together and put our differences aside and enjoy the beauty of music.”

Chatham County Line (CCL) had been scheduled to play their trademark song “Living in Raleigh Now” with the Steep Canyon Rangers, so in their absence, the band played a full set. A guest joining them on stage was Brenda Evans, the granddaughter of folk and blues musician Elizabeth Cotten from North Carolina, known for her left-handed guitar style and song “Freight Train.” Evans sang a song written by Cotten and her six grandchildren, “Shake Sugaree.”

Introducing “Living in Raleigh Now,” CCL guitarist/singer Dave Wilson said,“We have purchased a headstone because this is the last time this song will be performed.” They wrote the song the first year IBMA was held in Raleigh and the lyrics recount the history of bluegrass music from Bill Monroe, to Earl Scruggs, and with this punchline, IBMA’s locations: “What was born in Kentucky, moved off to Nashville, is living in Raleigh now.”

Before selecting the next IBMA festival location, maybe organizers should have considered the difficulty of working a 4 syllable word like “Chat-ta-noo-ga” into song lyrics.

But turning the page from Raleigh to Chattanooga just starts a new chapter in IBMA’s story, and the most compelling plot-line revolves around musicians and community supporting one another and “a genre that’s going to live forever.”