Home > Articles > The Archives > Hot Rize: Pete Wernick’s Secret Ingredient

Hot Rize: Pete Wernick’s Secret Ingredient

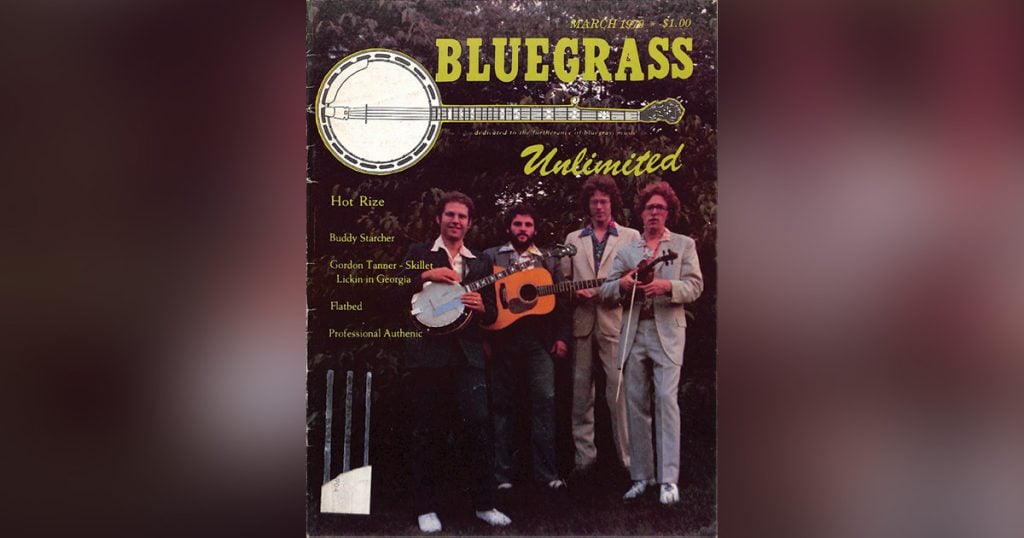

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1979, Volume 13, Number 9

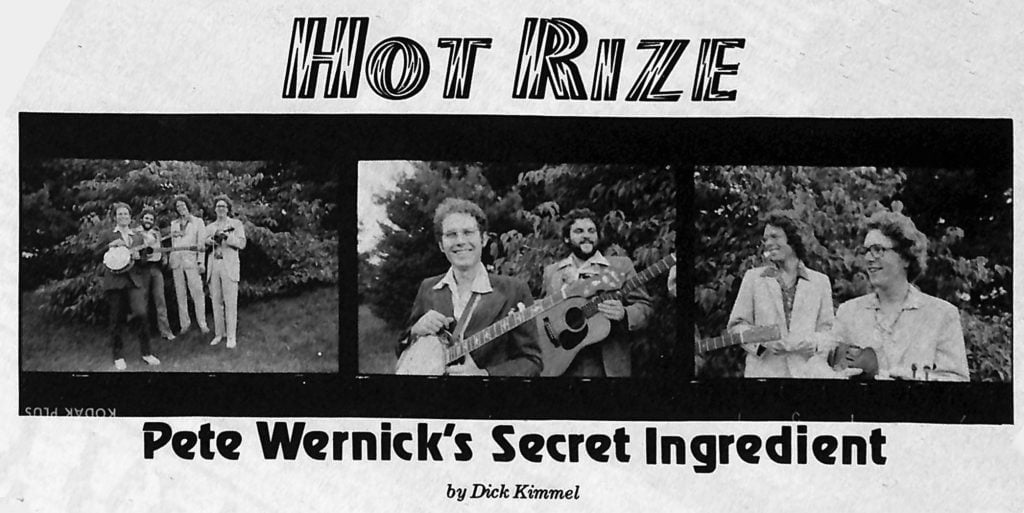

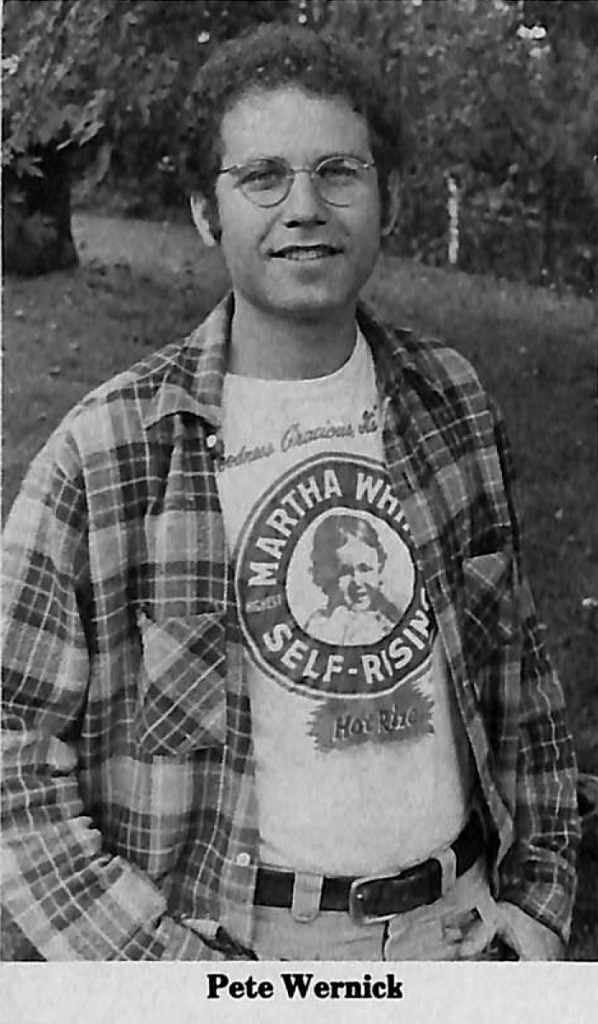

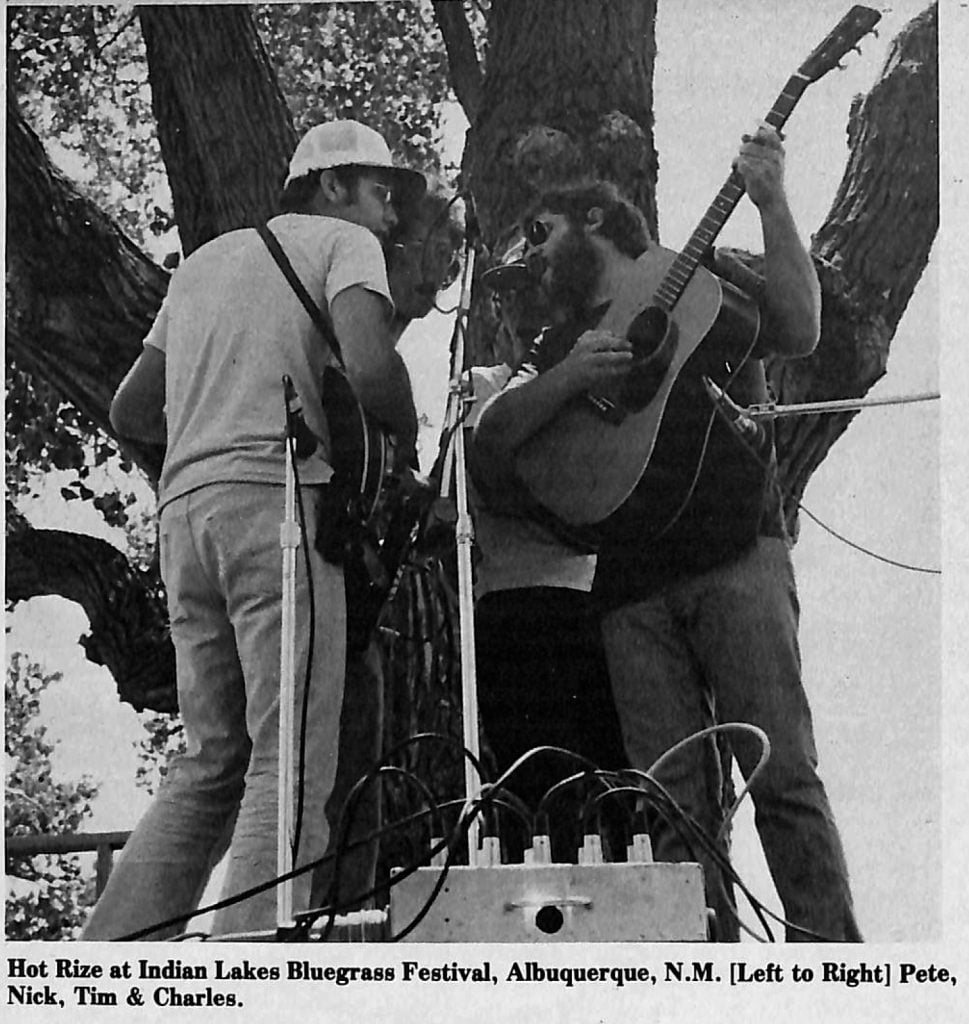

Mention “Hot Rize” to a bluegrass addict and you’re liable to get a variety of responses. Within range of Nashville’s WSM radio, “Hot Rize” not only brings to mind the secret ingredient responsible for biscuits made from Martha White Self-Rising Flour, but also Lester Flatt’s early morning bluegrass radio program and theme song that many folks enjoyed with their morning coffee. Within the past year Hot Rize has also meant a hot young bluegrass band. Pete Wernick on banjo, Tim O’Brien on mandolin and fiddle, Charles Sawtelle on guitar and Nick Forster on electric bass have made themselves known as Hot Rize to audiences in at least a dozen states in the short time they’ve been together. The fact that Hot Rize became somewhat of an overnight success was not a surprise to those who have followed these individual musicians in the past.

When Pete Wernick moved to Colorado early in 1976, he had made no definite plans to play music. The years he spent in upstate New York had been good to him, a product of his sense of professional direction and plain hard work, but the hard winters and rainy summers had gotten to be too much, so he moved west.

While the north means low pay and little recognition for most traditional musicians, Wernick recorded three well-recognized LP’s with Country Cooking, wrote Bluegrass Songbook and Bluegrass Banjo (which has sold over 100,000 copies to date) for Oak Publications, produced a series of Music Minus One instruction records, wrote many bluegrass songs and tunes of which some have almost been declared bluegrass standards (“Armadillo Breakdown,” “It’s in My Mind to Ramble”) and started his solo album for Flying Fish Records.

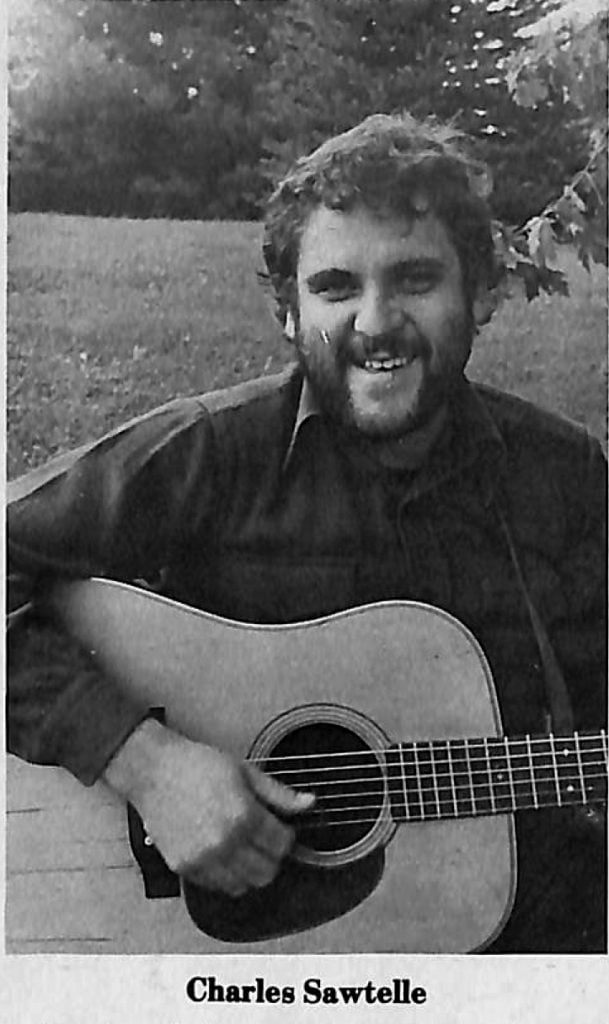

Shortly after arriving in the west, Wernick started playing bluegrass with Warren Kennison and Charles Sawtelle. Sawtelle was an experienced bluegrass guitarist who had played with The XX-string Bluegrass Band (Bluegrass Unlimited, March 1971) and The Monroe Doctrine (Bluegrass Unlimited, September 1973). Wernick, Sawtelle, and Kennison became known as The Rambling Drifters. According to Wernick, “Any place I go I want to be in a bluegrass band, even if I have some other professional objective which may not even be music. I’m a banjo player and you can’t stay in shape as a banjo player if you don’t play regularly. I just like it, anyway. So I got this band together with Charles (Sawtelle) and Warren Kennison within a couple of weeks after arriving in Denver”. The band was an informal one, exemplified by the fact that they were not only known as The Rambling Drifters, but also as The Drifting Ramblers, The Lonesome Drifting Rambling Cowboys and The Rebuilt Ramblers.

Like Wernick, Charles Sawtelle was a bluegrass musician in his thirties. Sawtelle’s father was in the oil exploration business so the family moved from his birthplace in Texas throughout the western United States and Canada. He had learned some steel guitar by the late 50’s and by the early 60’s was starting flat-top guitar. “I really couldn’t play. I just started out watching people that played. My brother had left a guitar at home and I didn’t even know how to tune it. I looked at a record album cover to see where the pegs were. I figured if I looked at a record jacket of Josh White or somebody that had a guitar, I’d be able to take the knobs on the guitar and position them exactly where they were on the record it would be in tune. Of course it didn’t work”. Sawtelle’s persistence paid off and eventually he began to learn bluegrass guitar with the help of Colorado musicians. Throughout the 60’s and 70’s he performed with a number of groups and eventually settled down as the manager of the instrument shop for the Denver Folklore Center. At that time he was also playing on a part-time basis as well as collecting old Martin guitars, elderly Cadillacs and working with his own Sawtelle-Wilson Sound Company which has provided sound for concerts by the likes of John Prine, John Hartford and Joan Baez as well as some of the larger festivals in the area (Colorado Bluegrass Festival and Winfield, Kansas). One of Sawtelle’s part-time involvements was The Rambling Drifters. As he puts it:

Sawtelle-I’ve had ten Fiddle players and twenty bass players”.

Wernick- “At different times”.

Sawtelle- “There were just three of us, but we always played as a four or five piece band. Tim (O’Brien) was our usual fiddle player, but he was also playing with the Ophelia Swing Band”.

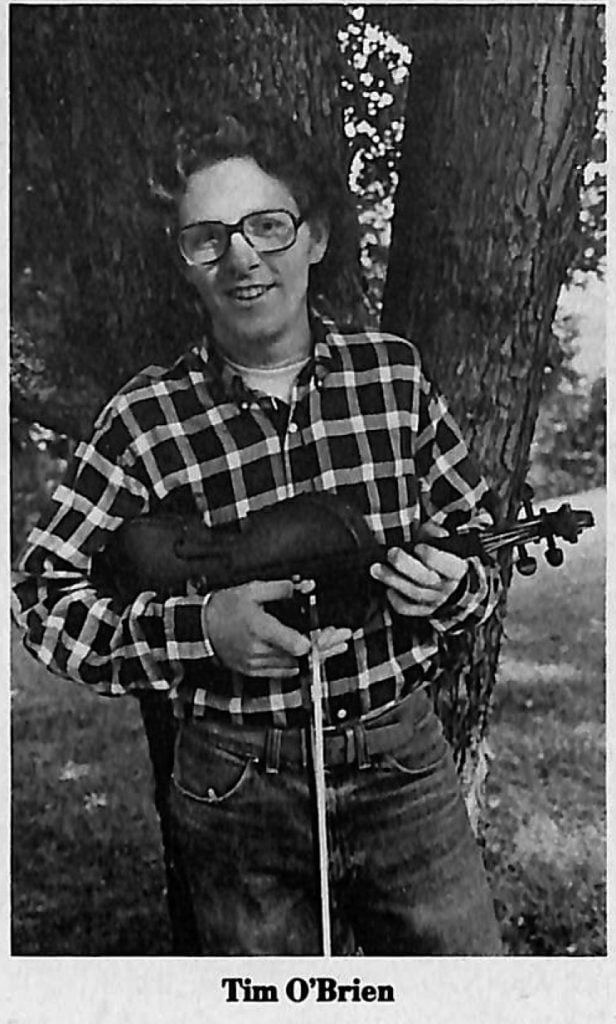

For a musician in his mid-twenties, Tim O’Brien has carved out quite a niche for himself. He’s known as not only a fine bluegrass performer, but also a top-notch old-time as well as swing musician. He’s been featured on ten LP’s including a solo LP “Guess Who’s In Town – Tim O’Brien” (Biscuit City 1317), which includes his fiddling, mandolin, lead guitar and fine vocal work on an assortment of old-time, swing and bluegrass arrangements. O’Brien was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, to a musical family. “My Father played the banjo-mandolin and my mother played the piano. And of course, we all sang, especially my sister Mollie and I”. He gained an early exposure to bluegrass and other forms of music through the folks at the WWVA Jamboree (especially Roger Bland, a banjoist who has since played with Lester Flatt) and by playing guitar in a variety of performing bands. O’Brien was part of West Virginia Grass, a band which played regularly in and around his home state. After a short stint at Colby College in Maine where O’Brien learned mandolin and played in another band, The Northern Valley Boys, he took to the road as a solo act in western ski areas and in the “old town” section in Chicago.

O’Brien – “The fall of 1974 found me in Boulder, Colorado, working at a music store and playing fiddle in a band called Towne and Country Review. I was drafted into the newly formed Ophelia Swing Band where I played mostly guitar at first, but later mandolin and fiddle. We played swing music of the 30’s, sort of like Hot Club of France, but with vocals and more arrangements. The rhythm section of Dan (Sadowsky), Duane (Webster), and Chaz (Leary) was great and it really built up my chops”.

With The Ophelia Swing Band, O’Brien recorded a very popular LP, “Swing Tunes of the 30’s and 40’s” (Biscuit City 1313), a unique recording of swing by this mostly acoustic string band. During O’Brien’s last year with Ophelia he would frequently sit in with Wernick and Sawtelle in The Rambling Drifters. It was during this period that O’Brien, Wernick, and Sawtelle did some recording together for O’Brien’s solo LP (Biscuit City 1317) and Wernick’s LP “Dr. Banjo Steps Out” (Flying Fish 046).

The Dr. Banjo LP had a number of elements that eventually led to the association of O’Brien, Wernick and Sawtelle in the context of a band. Wernick had been fooling around with phase-shifted banjo and what he calls “Niwot” music. (Niwot is a town near where Wernick lives in Colorado). Wernick’s use of the phase-shifter has been both an inspiration to bluegrass buffs and source of contention among them. He has been using it for a number of years.

Wernick – “I first got a phase shifter in 1974. When I heard an electric guitar through a phase shifter, I just figured I’d like to hear a banjo through it. I went to 48th St. in New York, into the different music stores, using a pick-up on my banjo, which I normally don’t use. I tried a lot of our modern gadgets which give us our rock’n’roll sounds of today. I picked out an MXR Phase 90 and also a thing called a Mutron III, which I later got rid of’. He also used the phase shifter when he was with Country Cooking.

Wernick – “In the last version with the Fiction Brothers, I used it on stage on a few numbers every set. When it came time to record our album (“Country Cooking with the Fiction Brothers” – Flying Fish 019), I used it on one number so it was recorded as of 1975. It was only with the release of my album (Dr. Banjo Steps Out) that I really got into presenting it”.

The phase shifter produces a strange effect, to say the least, and an explanation of how it is produced should be in order. Wernick – “It is an electronic imitation of a Leslie organ speaker. A Leslie cabinet has two speakers that actually rotate in opposite directions and they get out of phase with each other causing cancellations of different frequencies. It was eventually figured out that it could be done by electrically altering a signal with tone-filters and transistors and put into a little box which sold for less than $100”.

The sound is definitely a banjo, but Pete is able to work with the tones the gadget produces.

It sustains the banjo a little bit. At festivals the mike gets plugged into the box and a wire just like the regular mike wire goes to the mixing board. The connectors are completely adaptable and it is low impedance just like most sound systems. It can be hooked up in a short time and then it’s just up to whether I step on the button; if I do, I get the phase shifted sound. It has a way of expanding the tonal properties so it’s a much broader sound. It accentuates the overtones”.

The bluegrass audiences have reacted to it in a variety of ways.

Wernick – “I had an incredible range of reactions. Like when Joe Meadows, who fiddles with Jim and Jesse heard it, he came up to the stage and wanted to know where he could get one. Alan Munde bought one the day after he tried mine out and he is now starting to use his at shows, I know for a fact that I like it, but I’m not into trying to present professionally music that a lot of people are turned off by. Generally the reactions have been very positive”.

On the “Dr. Banjo Steps Out” LP the phase shifted banjo was an integral part of Wernick’s Niwot music, which he describes as “basically bluegrass without guitar”. Wernick had put together the Niwot sound when jamming with Andy Statman without guitar back-up. Both Statman and O’Brien played the Niwot mandolin style on the Dr. Banjo LP. Wernick relates, “The first thing that attracted me to Tim O’Brien’s music is that he played this fantastic rhythm mandolin style, which is so easy to play banjo over. It just gives you so much beat that it picks you up and just floats you a long and you don’t have to worry about laying down a steady rhythm. He’d heard Andy (Statman) play and knew what to do. Most bluegrass mandolin players do not play that kind of rhythm”.

That mandolin rhythm coupled with Wernick’s banjo style is the basis of the distinctive sound of Hot Rize. The group officially formed early in 1978 as a result of the Dr. Banjo LP. The first group included Mike Scap on guitar, Pete Wernick on banjo, Charles Sawtelle on bass and Tim O’Brien on fiddle and mandolin, Niwot style. According to O’Brien, “The Niwot mandolin sound has to do with the chop, which is not really a chop at all. Chop means that it is stopped, the notes stop – you take your fingers off the frets or damp them. In Niwot you let the notes ring as much as you can and instead of playing only off-beats you play eighth notes (chords) emphasizing the off-beats. Also instead of standard bluegrass chords, I’ll play more open chords, and whatever adds to it; 7ths, cross-rhythms and things like that”.

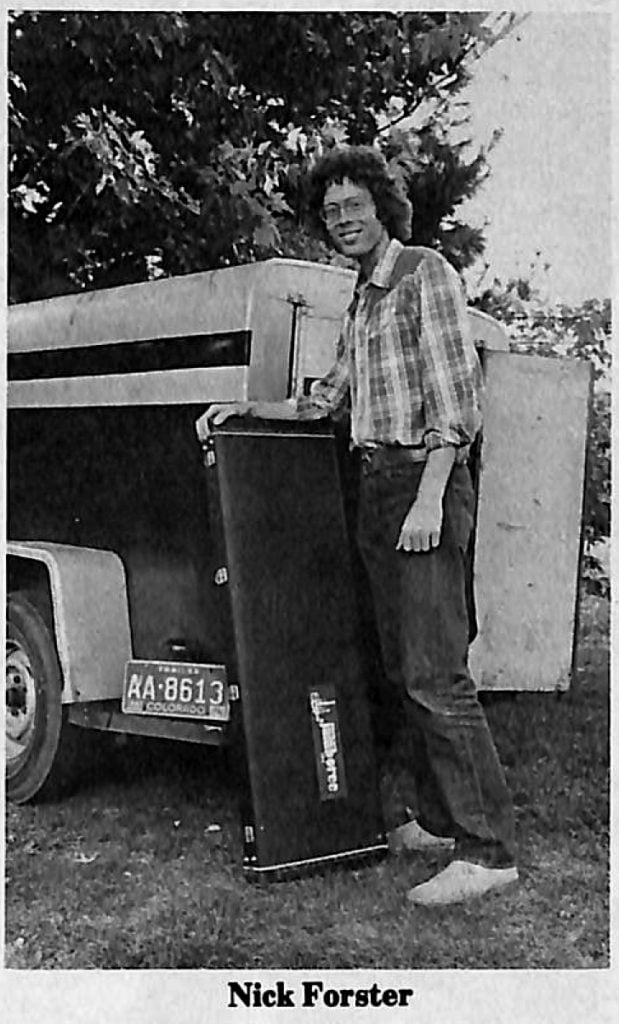

Nick Forster had had a loose association with the members of the band for many years. Forster had grown up in upstate New York with a background that included the musical interests of his father (jazz and swing), fooling with guitar and banjo at an early age, the square dances and fiddlers that are so much a part of life in the mountains of New York and Vermont and an introduction to bluegrass by a group from Poughkeepsie, New York, The Arm Brothers. The mid-seventies found Forster working as an instrument repairman at the Denver Folklore Center, which included such responsibilities as working the sound system for the Rambling Drifters and occasionally performing with them on Dobro, mandolin or as their square dance caller. When Hot Rize needed a replacement for guitarist Mike Scap in May 1978, Sawtelle moved to guitar and Forster joined the group on bass.

Wernick – “I am partial to the sound of electric bass if it is really played well and sensitively. It is capable of adding more punch. I chose it for my album, because I liked the way it sounded”.

Forster – “I try to make the bass sound as acoustic as possible. I also think one reason that I like it is that it is real easy to travel with”.

Sawtelle – “The thing that’s significant about our bass sound is that the amp on stage is used only as a monitor. The bass amp is turned down, just about as loud as an acoustic bass. It is wired directly to the mixing board and amplified and EQ’ed by the sound man.

Forster – “I really have a lot of control on how it sounds. It gives the soundman control over the volume and I have control over the tone on the amp. I can hear what the tone is like from the PA monitor on stage”.

To satisfy the instrument nuts, Forster uses a Fender Precision Bass and various components as an amplifier. O’Brien uses a “Nugget” teardrop-shaped mandolin made by Mike Kemnitzer of Nederland, it’s a German factory job made in the twenties or thirties”. Sawtelle prefers his 1937 D-28 Martin guitar, but occasionally uses a 1930 OM-28 for recording or a 1943 D-18 as a second stage guitar. About his guitar Sawtelle says, “I’d never own a herringbone at today’s prices. I wouldn’t even consider paying over $1200 for one. Well, I might if I wanted one so bad, because if you’re a bluegrass guitar player, it’s the tool you’ve got to have, the new herringbones are better for the money, but the old ones sound better because they’re aged. What would be good to say about my guitar is I’d like to sell it and see if I can get enough money to buy a new one”.

No one is really sure about Pete Wernick’s banjo. According to Wernick, “My banjo is an original 5-string flat head Gibson RB-1 from around 1930. Although it is not officially a Mastertone, it certainly has the kind of ring I like in a Mastertone. I got it from Porter Church in 1966 when he was with Red Allen. It’s been my only banjo all this time”. Typically RB-1 banjos did not come with the heavy tone-ring, but his banjo was either a special factory job or had been customized by the time Wernick acquired it from Church.

The group’s interest in phase shifters, the Niwot sound, hefty PA systems, swing and other forms of music may tend to eclipse the similar interests that brought these four musicians together. This common ground is a respect for traditional bluegrass. After spending even a short time with the band members, their repertoire comes as no surprise.

Wernick – “We do a lot of straight bluegrass material. This is a pretty important aspect of the band. Other than our original material, almost everything we do was written before 1955. We hardly do any material that’s like newgrass and yet we try not to do stuff that would be considered standards or shopworn material.

Wernick’s preference for traditional bluegrass is a product of his early associations in the New York City bluegrass scene. Wernick was attracted to banjo through early Flatt and Scruggs recordings he heard during the “folk boom of the late 1950’s”. During his college years at Columbia, study breaks involved picking a bow-tie Mastertone and serving as a disc jockey for his weekly show “Bluegrass Special” on WKCR radio. The show, which ran from 1964 to 1970, enabled Wernick to meet and interview many of the stars of bluegrass. “Also Washington Square during warm weather was just like a festival parking lot jam”. While in New York he met and played music with many musicians such as Winnie Winston and Steve Arkin. “David Grisman and Jody Stecher were very influential in cultivating my interest in the old groups. At this point I consider myself lucky to have heard early Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, etc. at that stage because I got into bluegrass earlier on in my learning, whereas now people will listen to an awful lot of, well, Alan Munde, who is great but it’s not the roots. It takes folks a long time to develop a concern for the roots. I think it’s important to get as deep an understanding as you can of the basis of bluegrass as well as the later development of the music”.

The years Wernick spent in New York City introduced him to the banjo and the essence of bluegrass music. His musicianship developed while he was living in Ithaca, New York during the early 1970’s. “I’ve been developing in the last seven years or so under the influence of Tony Trischka. He’s just a fantastic player who improvises all the time and does things at a hard technical level. He has very few technical limitations and makes you want to learn to play what he’s doing”. With Trischka, Wernick recorded two Country Cooking albums, “14 Bluegrass Instrumentals” (Rounder 0006) which is one of the most revered twin banjo LP’s, and “Barrel of Fun” (Rounder 0033). Trischka also appeared on two cuts of Wernick’s Dr. Banjo LP. By completing a PhD in Sociology while in Ithaca, Wernick truly became Dr. Banjo.

It’s frequently fruitless to try to intellectualize the various facets of traditional bluegrass that work themselves into a modern band composed of musicians from outside the bluegrass belt. Wernick demonstrated his insights into this dichotomy of the northern bluegrass musician in his article “Confessions of a Bluegrass Musician from New York” (Bluegrass Unlimited, May 1977). It seems that one of the hardest things for musicians newly exposed to bluegrass to grasp is the idea of keeping the music simple so as to release the soul. This approach which is so much the essence of the music of bluegrass greats like Ralph Stanley is definitely a part of Hot Rize.

Wernick – “If you come down a little bit off of the best that you are capable of and just get into grooving on the tone of the instrument, the tone of all the band blending together playing right into the same rhythm, you can just enjoy it more. And when you enjoy it more, it just communicates better within the band and outside the band. Music doesn’t sound necessarily better, the higher the technical level. Music sounds good the more the musicians are getting into what they are doing”.

O’Brien – “In this band we all can play some pretty bizarre stuff, but we all really try to not step too close to the edge ever”.

As with any band, Hot Rize is a product of a group of musicians. Besides being a group of real comedians, their abilities in a number of different areas combine to make a unique band. Charles Sawtelle is a seasoned lead and rhythm guitarist who also supplies the band with sound system and recording experience. Bass player Nick Forster can repair instruments and call square dances, a definite asset at a rowdy wedding party. Either the swing-oriented mandolin and fiddle breaks or the strong lead voice of Tim O’Brien would be a spark plug for any bluegrass band. Add to this the experience and solid banjo playing of Dr. Banjo, Pete Wernick, and you have Hot Rize.

What can we expect of Hot Rize in the future? According to Wernick, “I think our style is still forming, but I would guess the main developments in our music will be writing and finding good material that fits us. And of course, we’ll be regularly checking our mailbox for invitations from people like Helen Reddy, The White House, etc”. O’Brien adds, “Of course, I’d like to have my own Cadillac, a Lloyd Loar and a fiddle-shaped swimming pool, but I don’t want to compromise the music. I take pride in the fact that we are putting out the real stuff and that people may know what is and what isn’t bluegrass after hearing us”. For the immediate future anyway, the band will be featured on two LP’s, the Kenny Kosek-Matt Glaser twin fiddle record and the upcoming recording by Hot Rize on Flying Fish. This month Hot Rize will be on their second eastern tour entertaining audiences in such locations as Chicago, Delaware, Virginia, New York and Pennsylvania.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thank you for this archived interview. Great writing and reading still.