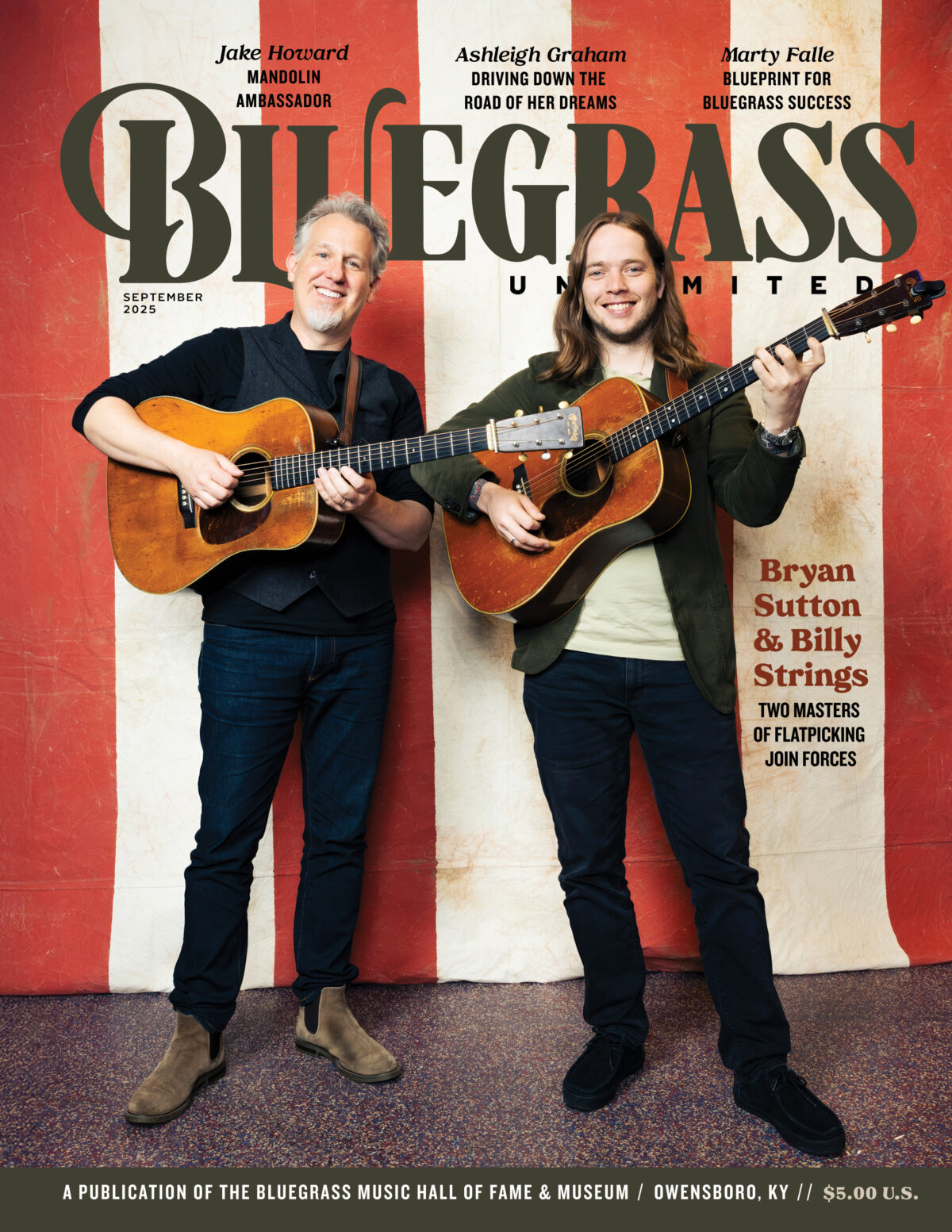

Home > Articles > The Archives > Hoke Jenkins—Pioneer Banjo Man

Hoke Jenkins—Pioneer Banjo Man

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1985, Volume 20, Number 3

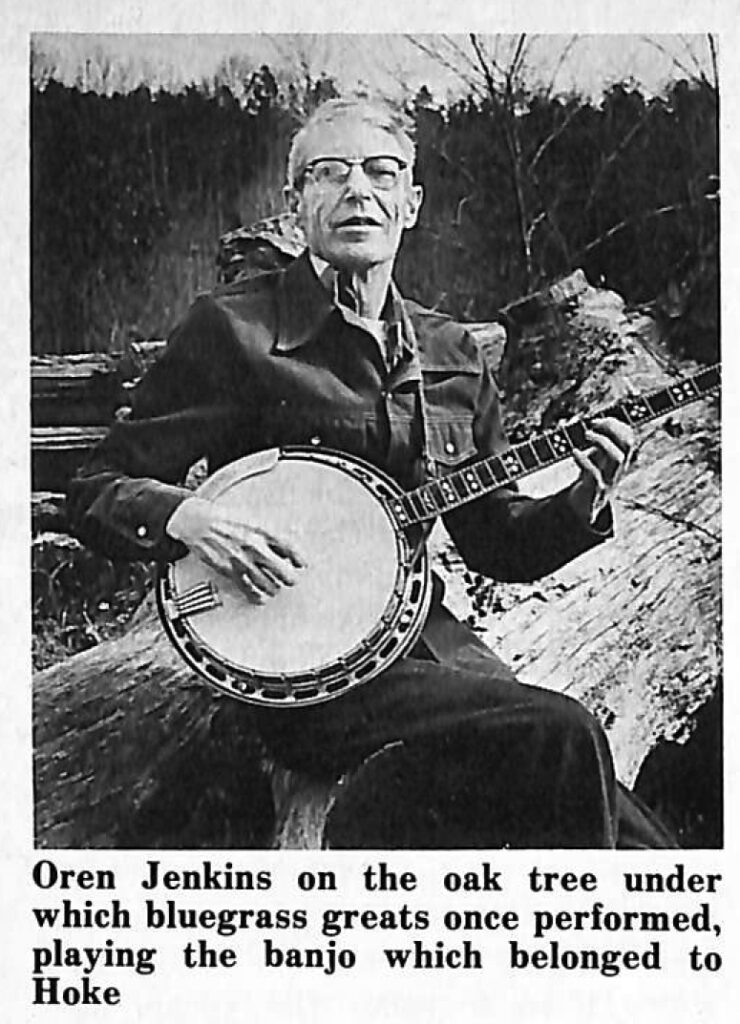

Some great names in bluegrass picked under an old oak tree in Harris, North Carolina many years ago. Oren Jenkins, who still lives in this rural community, remembers summer nights when he, his brother Hoke and his uncle Dewitt “Snuffy” Jenkins were joined there by the likes of Jim and Jesse McReynolds, and Wiley, Zeke and George Morris.

The tree no longer stands; Oren cut it down after it was struck by lightning. But huge pieces of the gray-barked stature now lie across the yard it once shaded. Oren —who Jim and Jesse insist would have been one of the very best banjo pickers ever had he pursued a musical career —still goes back to that spot to pick a round or two of “Salty Dog Blues” or “Sally Goodin’.”

As he rests on a log and plucks the five strings of brother Hoke’s custom- made, gold-plated Gibson banjo, Oren reminisces about the old days when Hoke was still alive and there was music all around here.

“On weekends, Sunday evenings, you know, we’d gather ‘round and pick awhile. There was always a big crowd, even when it was just family,” Oren says. “We played a little bit of everything.” Here, under this tree, Hoke and Oren both picked their earliest tunes. One brother went on to become a radio and show date performer in the 1940s; the other stayed home and tended farm and family. Hoke Jenkins is now remembered by many for his comic routines and unique banjo picking style. Oren played professionally only on rare occasions, such as the time he recorded with Jim and Jesse in Nashville.

Both Jenkins brothers learned to play instruments as naturally as they learned to walk and talk. Hoke, it seems was destined to make a career of bluegrass music, at least until his time came to put family life first.

Before tailoring his musical talents to a role that suited the Hoke Jenkins who was husband and father, he stayed on the move playing with Jim and Jesse, the Morris Brothers, Carl Story, Carl Smith, Curly Seckler, the Bailey Brothers, the Louvin Brothers, the Murphy Brothers and others.

His different three-finger style (with a “backwards roll”) on a five-string banjo, his novelty “washboard” act, and his grand showmanship, all account for his being considered one of the great contributors to old-time country music. A Hoke Jenkins Memorial Award is presented every year at the Snuffy Jenkins Old-Time and Bluegrass Music Festival in Cliffside, North Carolina to others who have made outstanding contributions to old-time country or early bluegrass music.

The award presented in honor of Jenkins has been given to his uncle Snuffy, Pappy Sherrill, and the Morris Brothers, Wade Mainer, Jim and Jesse, Mac Wiseman, Greasy Medlin, and Roy “Pop” Lewis.

Ben Humphries, promoter of the family-oriented festival remembers a story about Hoke’s dad, Roy. It gives an idea of the environment in which Hoke grew up, the forces that made him “one of the pioneer banjo players of his day along with Don Reno, Earl Scruggs and Snuffy Jenkins.”

“Roy never went anywhere. He was born and raised in a rural North Carolina community called Harris,” Ben explains in relating the story. “At sixteen, all he did was work. Work, work, work. He wanted to be around where the girls were. Well, he made a little money working for a neighbor one summer, enough to buy some clothes to wear out around the girls. He caught the CC&O railroad train one Saturday afternoon in Harris and took it to Forest City.

“He got to downtown Forest City and there was a fellow standing on a corner playing a fiddle. Well, Roy, he thought that was the prettiest thing he ever heard in his life. The man was wanting to sell the fiddle, but he wanted five dollars more than Roy had, so Roy said he finally let him have the other five dollars on credit. He spent all his money and didn’t have enough to buy a railroad ticket home, so he walked the ten miles from Forest City to Harris.

“He said he played that fiddle every step of the way and by the time he got home, he had already learned to play a couple of tunes. It was just a matter of time before his younger brothers started making instruments. I think Snuffy fashioned some sort of a banjo out of a wagon hub.

“Hoke came along a little later, (August 4, 1917). He was born into this environment. Nobody I’ve talked to in the family can put their finger on Hoke’s learning to play,” Ben continues. “He just grew into it; he heard it everyday.”

If only Hoke were here to tell it himself. He died in 1967 at the age of 50. He was packing up one morning to another of his just-for-fun Saturday night performances, this one in Marshall, North Carolina, when he suffered his third heart attack. The Smokey Mountaineers went on that day without him, not knowing the attack would be fatal.

The only explanation known for Hoke’s musical talent is that he was born with it and into a family that nourished that talent. Snuffy doesn’t claim to have taught Hoke to pick a banjo. “If I did, I sure don’t remember it,” he says. In fact, it was Hoke that introduced Snuffy to another instrument —the washboard.

The Jenkins boys-Snuffy, Verle and Dennis —and Howard Cole were playing a square dance in Gaffney, South Carolina. “Hoke didn’t have nothin’ to play. He grabbed the dadgum washboard and it just fit in like a top,” recalls Snuffy. “He’s the son-of-a-gun that got me started on that washboard.” At 75 Snuffy is still performing and always features an act or two with the comical washboard, which he has dressed-up with horns and other noise-makers.

Hoke was certainly comfortable on stage. He had been an entertainer even in school. His sister, Melba, now Mrs. Hubert Franklin, remembers Hoke as always having something going. “He was a slap-happy sort of person. Whatever came went, but he had a heart of gold.”

Everyone who knew him as a youngster says Hoke didn’t like school work. “He wasn’t too hot on that farming business either,” says Snuffy. But by the time Hoke was 16 years old he could play most any instrument, according to Melba.

When Hoke was young and still farming, he desperately wanted to go to Nashville, Oren recalls. Hoke didn’t have the money to go, so he sold a bale of cotton. The sale price got him to the Grand Ole Opry and back. “The Opry was the biggest thing in the world for country folks,” Oren explains. “Back then, everybody stayed up on Saturday nights listening to the Opry on the radio.”

After Snuffy became a hit playing the five-string banjo on WBT radio, Hoke began concentrating on the banjo too. His style was “similar to Snuffy’s, Earl Scruggs’, and many more, but it was unique,” says Zeke Morris. Referring to the way Hoke played the three-finger style, Snuffy says, “He had sort of a lope when he played.”

Jesse McReynolds explains it best. “Hoke played his rolls backwards from Scruggs style. Instead of going down two and up one, Hoke went down one and up two. He had a different style and sound on the banjo.”

Hoke’s first radio performance was with the Franklin Brothers, Melba’s husband Hubert and his brother Ellwood. They played on WSPA Radio in Spartanburg in 1939. “We played a country and western program every Saturday afternoon from one to five. Arthur Smith played back-up fiddle. Walson Epps was the announcer. He played accordion. We were just playin’ around for the fun of it,” Hubert tells.

They didn’t really play any show dates, but one trip to a fiddler’s convention in Edneyville produced a good story. They had only enough gas to get there and back and had little money, Hubert recalls. Hoke busted the head on his banjo and they used up all their gas looking for a replacement. “We didn’t have enough money for gas to get back home. We had to play our hearts out up there to win some money to get home on. We ended up winning a little on everything.”

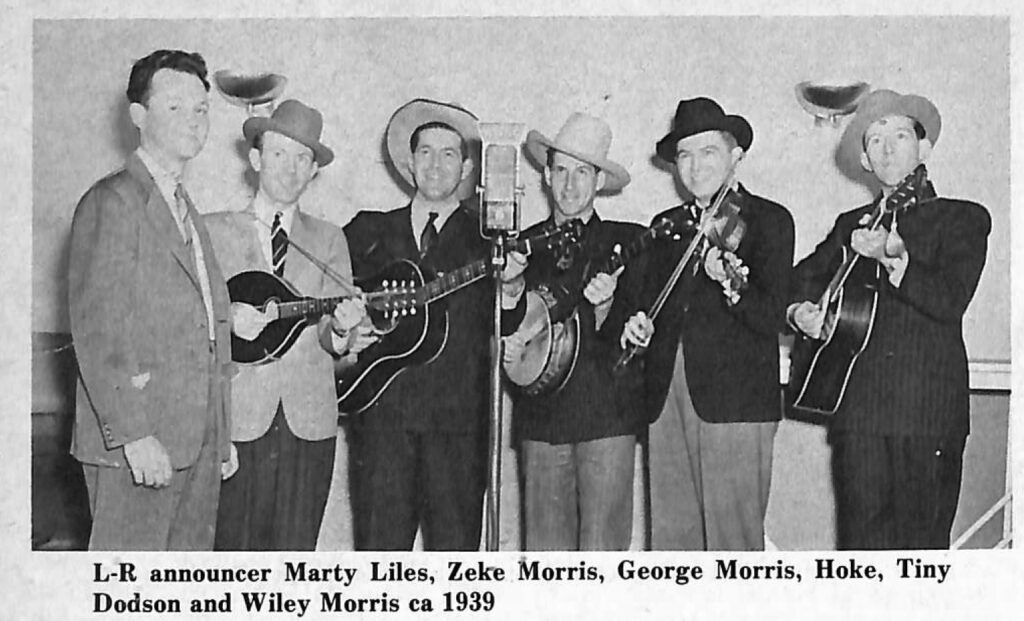

Running out of gas became almost a habit for Hoke. There would be many such stories to tell as Hoke’s career progressed. By mid 1939 things were beginning to take shape to head him into a professional music career. Snuffy was playing with J.E. Mainer and the Mountaineers on WIS in Columbia, South Carolina. George Morris was there too. Meanwhile, Wiley Morris had started the North Carolina Farm Hour on WWNC in Asheville with Tiny Dodson on fiddle.

WWNC expanded the show from 15 minutes to an hour-and-a-half program and Wiley invited in more performers. George joined him, mentioned Hoke Jenkins “played a pretty fair five-string banjo,” and then the two brothers drove to Harris “and tried Hoke out.” Wiley remembers, “We brought him back to Asheville with us and he stayed until he was inducted into the Army. It was the better part of two years. That probably tore a band up there.”

Zeke also joined the expanded Farm Hour. The band was extremely popular. “I guess you could say we were the most popular group anywhere in the south at that time,” says Zeke.

“For about a year and a half we broke all attendance records,” says Wiley. “We even outdrew Roy Acuff, not braggin’, in our hometown of Old Fort. We played a double date with Roy at City Auditorium in Asheville on December 1, 1940. We hold the biggest crowd that had ever been there til these rock’n’roll bands started playin’. We had ’em lined plum down the street down there.”

“We had a good clean, wholesome stage show along with the music,” Zeke adds. “Hoke was an extremely good banjo player and he was comical with it. He was as good an entertainer as you could find anywhere, and he was a good person along with it.”

Hoke’s timing was a little off from the Morris Brothers’ when he first joined them, but they “changed him a little bit.” He played “a little harder” than Scruggs, who at 16 later replaced the drafted Jenkins, but “see we had Hoke Jenkins before we ever got Earl Scruggs,” says Wiley. Scruggs is said to have played more smoothly; every note was perfect.

Wiley sums the two banjoists’ talents: “I’d rather play with Hoke and Earl Scruggs as any two I ever played behind. I could play good with either one of ’em.”

Wiley says he and Hoke were as close as brothers. “We was the closest to not be no kin whatsoever. We was real good friends when we wasn’t playin’ and when we was playin’. Me and Hoke Jenkins dated together, slept together, ate together, in fact we just lived together. We even married girls from the same area up here.”

Wiley also says he got Hoke and Rose Lyons together. “I had a date with her and Hoke had a date with Ethel Clontz. Ethel wouldn’t go with Hoke, so I got Rose to go with him. He ended up marrying her.”

Rose says the first time she ever met Hoke was in the radio station there in Asheville. She was there with some other girls to audition for a talent show. Rose was only 16 at the time, and “you know how us country girls were about country musicians!” She was from a wide place in the road called Candler, near Asheville. Hoke spotted her somehow, walked over to her at a break, put his banjo in her lap and said “hold that. I’ll be back in a minute.”

They were married two months later, just before Hoke left for basic training. He was one of the first drafted for World War II. “I wasn’t gonna let that man get away, army or no army,” Rose admits. She tells how Hoke cut part of his toes off during basic training at Fort Jackson. “He said he didn’t do it on purpose, but it kept him from going overseas.”

Snuffy remembers visiting Hoke at Fort Jackson. “I went out there one night. They were in a pup tent heated with an ol’ pot-bellied stove, coal. I got out there and I heard that banjo just a ringin’ and smoke a boilin’ out of that little ol’ tent.”

The Army may have broken up one band, but it wasn’t going to stop Hoke Jenkins from playing. “He had his banjo right with him. The guys would come out to our house, which was off base,” says Rose. “Even the Yankees who didn’t care a hill of beans about country music would come and listen.”

Hoke and Rose moved around while he was in the Army, a pattern they would continue for a while later because of his professional career. They left Ft. Jackson for Goldsboro, North Carolina and from there went to Norfolk, Virginia. He served four years and 11 months. When Hoke was discharged in 1945, he joined Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers on the Mid-Day Merry-Go- Round—a two-hour program on WNOX, Knoxville. Various performers participated in the Merry-Go-Round, including Molly O’Day, the Carlisle Brothers—Bill and Cliff—and Archie Campbell, and many others.

“Country music was doing good then. They made good money right after the war,” Rose says.

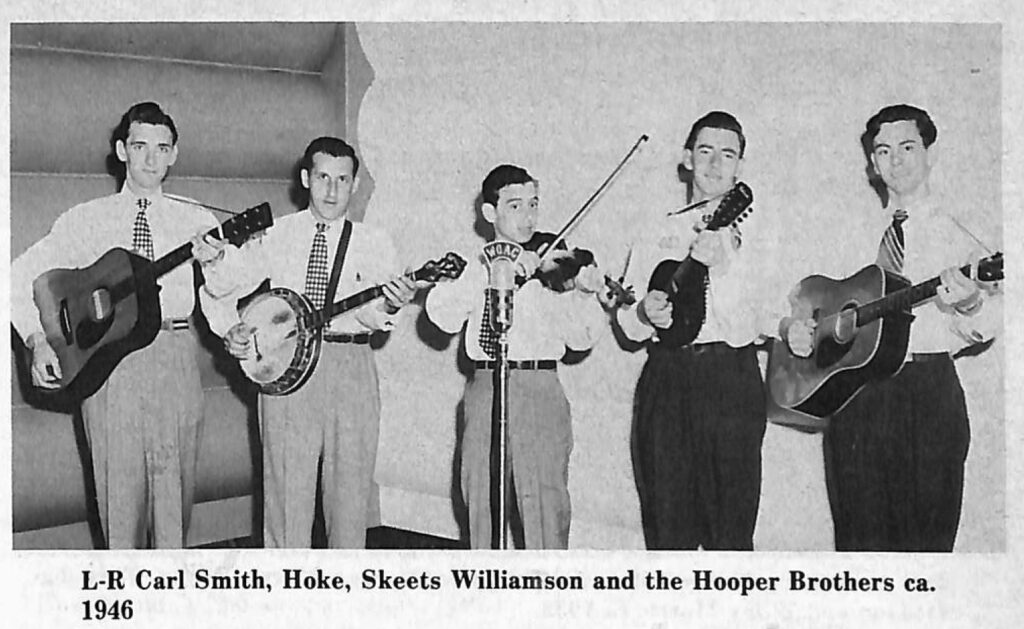

Hoke split from Carl Story after about a year. He wanted to be his own boss, Rose explains. That was when Hoke Jenkins and the Smokey Mountaineers were first formed. Carl Smith, Jack and Curley Shelton, Skeets Williamson and Hoke joined forces and returned to WWNC’s Farm Hour. That lasted about two years.

“With the radio business, they did well if they stayed two years,” Rose explains. Profitable show dates won though the radio exposure ran out after awhile. “It would get old,” she said.

Hoke and Carl moved on to Augusta, Georgia. The Sheltons stayed behind. Augusta was good for Hoke; here he was joined by Jim and Jesse McReynolds and Wiley Morris returned to his side. It was from here, too, that Carl Smith went to the Grand Ole Opry and hit the big time. The Hooper Brothers from Madison County played with them there for a short while. “They didn’t stay long,” says Rose. “You can get the boy out of the country, but you can’t get the country out of the boy. They went back home.”

Fred, Dewey and John Murphy, who were real young but accomplished musicians, played with Hoke in Augusta for a short while. Fred recalls, “Hoke was very persuasive, because we were not ready to go with him. It sounded like a good opportunity for us, but John was still in high school, and Dewey and I had jobs that we could not leave suddenly. Hoke prevailed, however, and Dewey and I went with him. John dropped out of high school to go back with us when we returned to Augusta after Christmas.

“Hoke was good to us, and we were impressed with the large turnout of people at all of the shows that we did with Hoke. While we were with Hoke, we played a double date with Snuffy Jenkins and his group from Columbia, South Carolina. That was a special treat for us,” Fred continued. “Our time in Augusta with Hoke was good for us. We learned much that was helpful.”

Wiley Morris was in the group part of the time the Murphy Brothers were there. Wiley was one of the better known singers of the day. Fred related a story about one of their performances: “Wiley was an excellent performer. On one show, he chased Highpockets, my brother John, around the auditorium and hit him on the head with his guitar. Wiley hit Highpockets harder then he intended to do, and it caused a slight crack in the back of his guitar. The auditorium roared with laughter.”

When the Murphy Brothers left, Hoke called Curley Seckler about working with the group. Curley said he would if he could bring along the McReynolds brothers to sing with him. “We were in Bristol trying to find work in the music business when Hoke called Curley,” says Jim McReynolds. “Really it was a job for all of us; a pretty good little ol’ job. Radio stations back then wouldn’t pay much, but there was some money there.”

Rose recalls Hoke taking “every penny we had” to drive up “to see what he was getting” before he gave the OK on Jim and Jesse. “Oh, can’t you call them,” she remembers saying to him. “They came and stayed with him through thick and thin.”

With a pretty good market for personal appearances in Augusta, “We played some pretty good shows down there,” Jim adds. The group lost Curley to Flatt and Scruggs in Bristol, but everyone kept playing.

Jim and Jesse say they got their sound together while they were with Hoke at WGAC in Augusta. That was in 1949.

“I more or less watched Hoke play the banjo, and learned to play the mandolin that way,” says Jesse. “I had never seen Scruggs play,” said Jesse. “I didn’t know there was a difference between a forward roll and a backward roll.” He says he had been working on the idea before he got up with Hoke, but perfected the technique on the mandolin with the banjoist’s example. “I feature my mandolin playing like Hoke did the banjo. I featured a backward roll all the time.”

Crosspicking on a mandolin is widely recognized today as Jesse McReynolds’ style. Snuffy says, “Ain’t many of ’em can do that.”

Sometimes while these musicians were just jamming, Hoke would switch his strings around to make his backwards roll sound like a Scruggs forward roll, according to Jesse.

Jim and Jesse also, during this time, worked on songs and put them down on record auditions for record companies. (There were no tapes in those days.) The brothers started being featured as a duet while they were with Hoke.

In those early days, bands also had skits in their shows. “A lot of comedy,” Jim says. “I think that was a big selling point if you had a good, fast-moving show. It’s hard to stay up there for two hours singing one song after another and never make people laugh. I think that’s one thing that’s missing in a lot of shows today. There’s some good bands out there, but you don’t see too many people getting into showmanship. To really entertain an audience you make ’em feel sad one minute and then the next one you get into you get ’em hollerin’ and laughin’ with you and that sort of rounds out the show.

“Hoke was always doing comedy. I guess he got a lot of it from Snuffy. He was a good showman,” Jim says. Snuffy probably told Hoke long ago what he still says about entertaining: “You got to make out like you’re having a good time, whether you are or not.”

The fun wasn’t just limited to the stage.

Hoke pulled his gasoline tricks with the McReynolds boys too. “We had a little thing going one time,” Jim tells the story. “Hoke was telling us what kind of mileage he was getting on an old Buick, I think it was, or Pontiac. We never did believe him. One night we were going to work a show. Hoke, he didn’t put any gas in the car. He was gonna prove to us what kind of mileage he was getting so we didn’t hardly make it to the date. He run out of gas and pulled over to the side of the road. He looked at the speedometer and said, ‘Now looky there, fifteen miles per gallon’.”

Wiley tells practically the same story of going out on a show or coming in from one. “Hoke would run out of gas and we’d be just sitting five miles out in the middle of nowhere. That’s the way Hoke would do. He’d say, ‘I just forgot to buy gas.’ He was forgetful on stuff like that.”

As Wiley remembers the appearances in Augusta, he says some places had good crowds, others didn’t. “Back in them days we was charging thirty-five cents and sixty or seventy-five cents, but when I first started it was fifteen and twenty-five cents general admission,” he says. “We was sponsored by schools and theatres; we wasn’t guaranteed nothin’. We furnished our own advertising and the people who sponsored us put up the advertising. At times we had good crowds.”

Rose says their luck finally ran out. “It finally got so bad to where they didn’t draw a crowd. People were going for bigger name groups and Hoke decided to quit awhile,” she says.

“But once you’re a musician and not trained for anything else; well, he tried the vending machine business in Charlotte,” she says. Hoke’s brother Oren says he worked for Stonecutter Mills in the dye house for a while, and also tried his hand at saw milling and farming. None of that suited Hoke either. For the meantime the vending machine business was not satisfying to Hoke, and he only stayed three or four months.

“The Bailey Brothers—Charlie and Dan—in Raleigh called and wanted Hoke to come play with them. We pulled up and went down there,” says Rose.

By this time Hoke and Rose had four girls. Edwina had been born while Hoke was in the service. Joyce was born while he was playing in Knoxville, Tennessee. Sherry had came four years later when Hoke had the early morning show in Asheville. Christy was born in Charlotte.

The Bailey Brothers had hired Tater Tate to play fiddle, and when Willis Hogsed left them for the Army, they hired Hoke too. Charlie Bailey had been quoted as saying, “Hoke was one of the few banjo players that can play banjo without using a capo on it… he could play anything.”

Another tale emerges when Hoke’s history in Raleigh is discussed. Charlie told the story many times like this: “Hoke couldn’t find an apartment. There was an apartment advertised in the paper and he went out there. Hoke said, ‘Yeah, I like it, I’ll take it’ .. and the old lady said, ‘Do you have any children?’ … he said ‘Yeah, I got four’ … and she said, ‘Oh, no, no children.’ Hoke said, ‘I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll get rid of ’em. You hold ’em and I’ll chop their heads off’ … the old lady was about to kill him.”

Hoke stayed in Raleigh only six months before changing stations again. “That suited Mrs. Jenkins (Hoke’s mother) to a ‘t’,” recalls Rose, “because it meant we were with her a couple of weeks in Harris, at least the girls and I were.”

Hoke’s last radio performance was with Jim and Jesse in Lexington, Kentucky. “Us and Curley was working together again,” Jim says. “We were looking for a banjo picker and we got Hoke to come work with us. He was with us in fifty-two when we did our first recording on Capitol Records. Hoke played the banjo on those first recording sessions.

“We had a good relationship with Hoke. He was a lot of fun to be around. Back in those days it was hard to make it in this business. There wasn’t too many big deals or a lot of money floating around, but we had a lot of fun,” says Jim. “One thing about the early days of this business, you had to believe in it and enjoy it because sometimes all the payoff there was was the enjoyment you got out of it.”

Rose says now, “Some weeks they would make money and some weeks they wouldn’t make any money. But we did just as well with six of us home and with one salary of a musician as I do now. It’s just a difference in the time and the economy.

“After Edwina got up in school, it was just a hassle for us to keep moving around,” Rose explains. “He decided he needed to quit and get them a home, so he did. His family came first.” They settled in Charlotte for four years. Hoke went to work for another vending firm —Saxon Vending Co. He worked his way up “until he was so good at it, they sent him here to High Point as branch manager. That’s how we ended up here,” Rose says.

“He always kept a country music band, though, and would play on weekends, for dances and Saturday night shows,” she adds. “As long as he could keep something like he had for weekends going, he was satisfied. On Friday and Saturday nights we’d go listen to him or go do our own thing. The girls weren’t real interested in country music and Hoke certainly didn’t want his girls in the music business; he knew what it was.”

One time he let his daughter Edwina sing on the radio. She tells: “My only claim to fame was a radio appearance in Augusta when I sang (more or less) “Easter Parade.” Some staff member of the station made a lot of mothers mad when she put me on the air instead of one of their cherubs and the only reason she did it was because I was Hoke’s daughter. Also, Augusta is where my sister, Joyce, sat on Little Jimmy Dickens’ knee when she was about four years old. She seemed almost as big as he was. Joyce should have been the one to sing; she had a rendition of “Chattanooga Shoeshine Boy” that was super … and she can carry a tune!”

If you had asked Edwina the child what her father did for a living, she probably would have said, “I think he rides around in a car and makes music,” she admits today. “A child’s viewpoint of parental employment has a lack of awareness that doesn’t go away until years pass and the child grows up.

“But he enjoyed what he did. He more than enjoyed it. If the phrase ‘having a blast’ had been used in the ’40s and ’50s, that’s what Daddy was doing in the music business —having a blast!”

She remembers his “playing the comedy for effect.” She says, “I’m not sure what he was doing one night, but he fell, and sat on his teeth that he had hurriedly stuck in his back pocket. He often removed a partial plate to be snaggle-toothed. I’ve often thought that his travel was probably a little uncomfortable for several days after that.”

Reflecting on her father’s talent as a banjo player, Edwina adds, “All of us like to be proud of friends and family when they’re the best at something and even though he’s gone now, the sound of a five-string banjo, well-played, gives me a strange feeling—he was one of the best pickers ever and I’m glad he was my Dad.”

Edwina also remembers her dad enjoyed keeping in touch with musicians after he left full-time music making. “Jim Lunsford, Carl Smith and, of course, Jim and Jesse McReynolds are the ones I can particularly remember coming by and calling. I haven’t seen Carl in years, but when Jim and Jesse play nearby, it’s like seeing family to go see their show and visit with them. Every time I see them, I think about all of us piled into their convertible for what had to be the coldest trip in the world from Lexington, Kentucky, to Harris, North Carolina. For two guys like that to contend with us was great, but we probably did our part toward destroying their desire for family life.”

All the times were good as far as Rose is concerned. Whether they were on the go, moving from one station to another, or after they settled down. “They were all good to me. I enjoyed going around. It was Hoke who felt he needed to make a home for the girls. What made him the happiest after he quit the business was a house we built. “This is the first house we ever built together, isn’t it,” she remembers him saying to her with a huge grin on his face. He was proud of their home. “People said Hoke had no business in the music business because he was such a family man.” But he did combine the two to his satisfaction.

Lots of times during those years in Charlotte and High Point, when Hoke’s only performances were on weekends for his own enjoyment, he would play his banjo a lot at home. “He’d get his banjo out and play just like he needed to practice more than anything in the world,” Rose says smiling. “He’d close the bedroom door, it didn’t matter if the television was playing or whatever, and he’d practice. Sometimes I would hear him just a’laughing, remembering something that had happened on a trip or something.”

He pushed himself hard in those days. He was just the sort to stay busy, work hard, play hard. He suffered his first heart attack in 1965 and was in the hospital 28 days. Two years later he had a second and refused to go to the hospital. “He hated hospitals and wouldn’t go; he was still up going,” says Rose, who became a nurse after Hoke’s death. “I finally talked him into going to the doctor. He was in the hospital for ten days. I took him home on a Tuesday and Saturday he had his third one.”

That last heart attack came when he was packing up for a trip with his Smokey Mountaineers. “He just wouldn’t slow down,” says Rose. “But it would have been a living death for him because he wouldn’t have been able to do anything.

“There just wasn’t another one like Hoke Jenkins,” she concludes.