Home > Articles > The Archives > His First Love, The Guitar: Tony Rice

His First Love, The Guitar: Tony Rice

October 2002, Volume 37, Number 4

A lot of people were heartbroken when Tony Rice stopped singing. But he was not one of them.

“I don’t worry about it as much as people think,” he says offhandedly. “The guitar was always the main thing for me. I spent four years with David Grisman where I didn’t sing at all. I got so far into that music, in fact, that I didn’t care if I ever sang again. As I was losing my voice, I was getting more interested in the guitar again; I was getting back to where I was during the Grisman years.”

For the rest of us, though, it’s hard to forget the sound of Rice’s burnished baritone as it delivered contemporary folk songs with conversational ease, as on the 1996 Rounder collection, “Tony Rice Sings Gordon Lightfoot.” Or the thrill of hearing his voice rise high and lonesome on the classic 1975 album, “J.D. Crowe & the New South,” or on any of the Bluegrass Album Band projects that Rice has headed up.

“But that was the whole problem,” Rice points out. “My voice gave out from all the abuse of trying to sing too high for too long. Because I was so dedicated to that high, lonesome sound, I was singing out of my range for all those years. I was trying to get my vocal mechanism to do something it wasn’t designed to do. It was a gradual thing over the years; I first noticed something was amiss way back when I was with Crowe.”

At the 1993 Gettysburg Bluegrass Festival, Rice’s voice gave out for good. The diagnosis was dysphonia, a cramping of the throat that prevents singing and gives even the speaking voice a perennial trace of hoarseness. Many musicians would have been devastated by such a setback, but Rice insists that he shrugged it off and returned to his first love, the guitar.

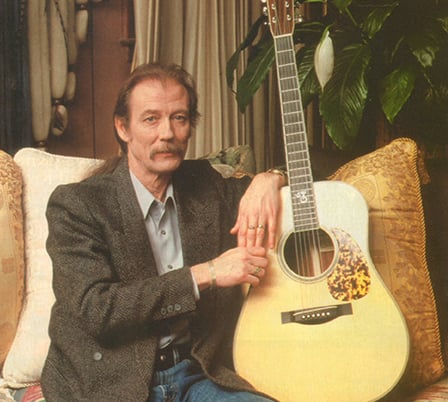

He certainly seems at peace with himself sitting at a wooden picnic table backstage at the Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Md. Having just finished an afternoon set with Peter Rowan as part of the Jamgrass touring package. Rice is enjoying an early dinner. A long mustache curls around his mouth, and his sandy hair is pulled back in a ponytail that reaches nearly to his waist. A dark blue shirt and a bright blue necktie reinforce the deep blue of his eyes.

“I play in several different situations these days,” he explains, “but over the past three years, about eighty percent of my dates have been with Peter. Once in a while, I’ll play in a quintet with Dan Tyminski, Sammy Shelor, and Rickie and Ronnie Simpkins, and Rice, Rice, Hillman & Pedersen also do a handful of dates each year. In addition, the Tony Rice Unit will do a show now and then, though the personnel is a continually changing concept.

“For the most part, though, I’ve been working with Peter. I love it because it allows me to play three different styles of guitar. I can play rhythm guitar in that bluegrass style I’m used to. I can play solos, which I do on almost every song. And I can express myself as an accompanist to a singer, which is something I could never do when I was singing myself. There’s not enough room in the brain—at least in my brain—to do both at the same time.”

Rice excelled in all three roles that afternoon. Rowan handled all the lead vocals from the center mic. To his right was the rhythm section of mandolinist Billy Bright and upright bassist Bryn Bright, a married couple from Austin, Texas. To his left stood Rice.

Rowan (an alumnus of both Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys and Jerry Garcia’s Old And In The Way) began the set with his self-penned hippie anthem, “Panama Red,” and then dug backwards into his roots. The set’s highlight was the old shape-note hymn, “Wayfaring Stranger,” and Rowan’s heartfelt vocal was followed by Rice’s guitar break.

Altering the melody without adding more notes. Rice proved that a slow- motion solo can be as dazzling as one on fast-forward. Such was the level of invention that the hymn segued easily into George Gershwin’s “Summertime,” and Rice was soon trading licks with both of the Brights.

For the encore, Rice put Appalachiana and jazz together in the form of an unaccompanied instrumental version of “Shenandoah.” The guitarist’s quicksilver, single-note runs roamed freely through the substitute chords he inserted into the old-time song. The familiar, melancholy melody would rise to the surface, submerge beneath a new burst of harmonic exploration and then surface again. The arrangement, which appeared on the Tony Rice Unit’s 2000 album, “Unit Of Measure,” remains one of Rice’s best vehicles.

That was followed by “Free Mexican Air Force,” another Rowan composition, and Rice answered the singer’s every whoop and yodel with a guitar fill. It almost became a duet even though Rice never opened his mouth.

“Backing up a singer,” he explains, “requires a certain thought process, because your phrases have to supplement the singer both musically and lyrically. I would play a totally different phrase on a song like ‘Old Santa Fe’ than I would on an old Bill Monroe tune, just as a murder ballad requires more dramatic phrasing than a love song, which needs a gentler touch.

“That’s what I like about this situation; I can reveal myself artistically not only as a soloist but also as an accompanist and as an ensemble player. And it’s a great ensemble. Bryn and Billy are amazing musicians. I’ve always been very critical of bass players, but Bryn leaves nothing to be desired. She plays in time and in tune and takes incredible solos.”

“Billy & Bryn Bright,” the couple’s all-instrumental debut album, was released on Blue Corn Records. It featured the Brights, Rice, Rowan, and fiddlers Vassar Clements and Eamon McLaughlin in various combinations on all ten tracks, nine of them written by Billy. Favoring neither the fast and lonesome sound of traditional bluegrass nor the freewheeling jamming of newgrass, Billy’s tunes tend to be midtempo with strong melodies, rolling rhythms and obvious emotion, like those of Norman Blake.

The quartet of Rice, Rowan, and the Brights has developed quite a following over the past few years and has tried to capture some of that magic in the studio. But the group’s music has been changing so quickly that the musicians can’t decide what to release.

“Peter and I have recorded with Bryn and Billy,” Rice reveals, “but as we listened to the tapes, we realized that the songs have evolved so much that we may have to go back in and re-record some of them. But I’m thinking that this band would be best represented by a live recording.

“That’s because we have a special relationship with the audience we’ve developed. It’s an extension of the Grateful Dead audience, because Peter was involved in Old And In The Way with Garcia, but they’re connoisseurs of music. They don’t just show up to hear a drum beat; they want to be surprised. They’ll follow you wherever you go in a tune.

“A bluegrass audience is a listening audience. They want to hear that music in its purest form, so they’ll be quiet and restrained. That’s fine for traditional music. This is more of a dancing, whooping kind of audience. You can feel the energy coming off of them, and we feed that energy right back to them.”

Rice’s most recent appearance on disc is the third album from Rice, Rice, Hillman & Pedersen, “Running Wild.” As I noted in the liner notes to the album, this quartet doesn’t play together that often, but they are constantly drawn back together for recording projects. For Tony Rice, his mandolinist brother Larry Rice, and the two former members of the Desert Rose Band, Chris Hillman and Herb Pedersen, the glue that holds them together is a shared adolescence in the California bluegrass scene of the late ’50s and early ’60s.

The Rice brothers were born in North Carolina, but the family moved to California when Larry was four and Tony was three. Their father, Herb, was a welder who had moved to Los Angeles to find a better job. but he stayed in touch with his Carolina roots by forming on of California’s early bluegrass bands, the Golden State Boys, with his brothers-in-law. It was only natural that Herb’s sons—Tony, Larry, Wyatt and Ron—would end up playing the music on guitar, mandolin, guitar, and bass respectively.

Tony says, “The first record I remember hearing was a Columbia 78 by Flatt & Scruggs, ‘You’re Not A Drop In The Bucket.’ I don’t know how that music got into the soul of someone that young, but it did. Here I am at age fifty and it’s still in the blood. Maybe it was because of my family. For not only could I hear this music on a record, but I could sit in a room and see someone with the same instruments create that same sound.”

For native Californians like Hillman and Pedersen, this influx of eastern pickers was a godsend. These two teenagers first heard bluegrass as part of their interest in the folk-music revival and had fallen in love with the fast, hard picking and the eerie vocal harmonies. But their education had been restricted to records until actual bands started popping up on the West Coast.

“As much as I liked growing up in suburban Los Angeles,” Tony confesses, “I often felt out of place. One day I got brave enough to bring my guitar to school, but when I played all I got was a lot of ridicule. No one in a California elementary school even knew what bluegrass was. After that I didn’t take my guitar to school or even discuss music with my friends.

“In the sixth grade, my brothers and I formed a bluegrass band called the Haphazards—I always despised that name, I found it humiliating. But we got a few dates around Los Angeles, and then we got a Friday night TV show on channel 13, KCOP. Then all of a sudden my classmates began to admire me. They said, ‘We’ve been making fun of this guy for playing hillbilly music, but he’s on TV and we ain’t.’ Then I finally found some other kids who liked bluegrass, which was a great relief.”

He found them on September 5,1963, at a bluegrass and folk concert at the Ice House in Pasadena. The Haphazards were there; so was Hillman as a member of the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and Pedersen as part of the Pine Valley Boys. Also at the event were the Mad Mountain Ramblers, featuring David Lindley, and the Country Boys, featuring Clarence and Roland White.

Tony Rice had only been eight in 1959 when he first met Clarence White. White was only 15 at the time, but he was already playing guitar with a rhythmic forcefulness and a harmonic imagination that Rice had never heard before, not even on record. The younger boy was soon following his older hero everywhere he went, staring at his hands and memorizing every note in hopes that he too could someday play the guitar as something more than a background rhythm instrument.

“Clarence was an amazing player even at that age,” Rice insists. “He was playing mostly rhythm, but he was doing something magical that was different from what Lester Flatt and Jimmy Martin were doing. And when his older brother Roland got drafted into the army in 1960 or ‘61, the band was left with no one to play leads. Clarence figured out real quick that he could play those mandolin leads on the guitar. At first he copied Roland’s parts, but he was soon inventing his own lines.

“He never gave me lessons or anything like that; we were just two kids hanging out together. But I would try to do everything he did, and when I couldn’t I’d invent something of my own. When word got out how good Clarence was, everyone wanted to play with him. He started hanging out with James Burton [Elvis Presley’s guitarist] and listening to Django Reinhardt. Just as I couldn’t match Clarence, Clarence couldn’t match Django but in trying he came up with something more daring than he’d done before.

“About that same time, I heard Doc Watson, who was playing leads on acoustic guitar much like Clarence was. They were different because Doc came out of old-time mountain music, while Clarence came strictly out of a bluegrass mode. But they were both brilliant; I can’t put into words how special it was to hear Doc live or on album in those early days. What people don’t realize is how much Clarence influenced Doc; they had a lot of mutual respect for each other.”

The Rice family moved back to North Carolina in the mid-’60s, and in 1970, the 19-year-old Tony Rice replaced Dan Crary in the Bluegrass Alliance, a group that contained Sam Bush, Courtney Johnson, and Harry “Ebo Walker” Shelor—three-fourths of the future New Grass Revival. In 1971, though, Rice joined his brother Larry in J.D. Crowe & the New South. By 1975, the band included Crowe, Rice, Ricky Skaggs, Jerry Douglas, and Bobby Slone, and that year’s album, “J.D. Crowe & the New South,” is still considered one of the top bluegrass albums of all time.

But Rice was itching to try some new things, and he left Crowe later that year. Banjo player Bill Keith had just left Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys to make a more adventurous solo album, and Rice signed up to do the guitar parts. Playing the mandolin was a young, frizzy-haired New Yorker, David Grisman.

“Grisman brought along this tape he’d made with [fiddler] Richard Greene and [guitarist] John Carlini,” Rice says, “and I had never heard anything like it. Coming out of these bluegrass instruments was a form of modem string band jazz. The chord changes were unusual and the solos were wild, but still everything was pleasant to the eardrum. I remember thinking, ‘Boy, it would be an honor to someday be a part of that. ’

“Before too long I was. Carlini was leaving to play with the Ice Capades Orchestra and Greene was going out with Loggins & Messina. Grisman was left with this music and he needed guys to play it. I had the bluegrass background Grisman was looking for, but I had my work cut out for me. My only knowledge of modem jazz was listening to it and loving it; I had no idea how to play it on guitar. Carlini, who became a good friend, tutored me and I had to learn music theory for the first time.

“I first heard jazz when I was a sophomore in high school. My girlfriend had an eight-track tape player in her car, and one day when she turned the car on, Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’ started playing. It grabbed me the same way Flatt & Scruggs had back in 1955. I still listen to a lot of jazz—Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Pat Metheny, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Oscar Peterson, and Eric Dolphy. But I’m just as likely to put on Jascha Heifetz or Bill Monroe.”

After four years with Grisman, the guitarist formed the Tony Rice Unit, an instrumental ensemble that pursued Grisman-like string band jazz but with Rice’s compositions and bluegrass-flavored sound at the center. That has been his primary vehicle over the past 23 years, but he has also done projects with the reunited Rice Brothers and Rice, Rice, Hillman & Pedersen as well as solo vocal albums.

In 1982, Rice founded the Bluegrass Album Band, a group that usually included Bobby Hicks and/or Vassar Clements on fiddle, Jerry Douglas on resonator guitar, Todd Phillips on bass, J.D. Crowe on banjo, and Doyle Lawson on mandolin. They originally came together to do one album as a tribute to traditional bluegrass, but the disc proved so popular that the band has now released six albums. The latest release was an all-instrumental project, out of deference to Rice’s throat troubles.

“The voice is slowly getting better,” he reports. “No one knows for sure, but I’ve had two good speech therapists. It’s helped some, and I hope that I’ll get back to it. I got brave enough recently to jump in on a low harmony part on the Stanley Brothers’ ‘White Dove.’ But there’s no promise that I’ll ever get on stage and sing the entire Gordon Lightfoot repertoire again.”

Geoffrey Himes writes about music for the Washington Post, No Depression. Country Music Magazine. Chicago Tribune, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the Oxford-American. the Baltimore City Paper, and other publications.

13, KCOP. Then all of a sudden my classmates began to admire me. They said, ‘We’ve been making fun of this guy for playing hillbilly music, but he’s on TV and we ain’t.’ Then I finally found some other kids who liked bluegrass, which was a great relief.”

He found them on September 5,1963, at a bluegrass and folk concert at the Ice House in Pasadena. The Haphazards were there; so was Hillman as a member of the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and Pedersen as part of the Pine Valley Boys. Also at the event were the Mad Mountain Ramblers, featuring David Lindley, and the Country Boys, featuring Clarence and Roland White.

Tony Rice had only been eight in 1959 when he first met Clarence White. White was only 15 at the time, but he was already playing guitar with a rhythmic forcefulness and a harmonic imagination that Rice had never heard before, not even on record. The younger boy was soon following his older hero everywhere he went, staring at his hands and memorizing every note in hopes that he too could someday play the guitar as something more than a background rhythm instrument.

“Clarence was an amazing player even at that age,” Rice insists. “He was playing mostly rhythm, but he was doing something magical that was different from what Lester Flatt and Jimmy Martin were doing. And when his older brother Roland got drafted into the army in 1960 or ‘61, the band was left with no one to play leads. Clarence figured out real quick that he could play those mandolin leads on the guitar. At first he copied Roland’s parts, but he was soon inventing his own lines.

“He never gave me lessons or anything like that; we were just two kids hanging out together. But I would try to do everything he did, and when I couldn’t I’d invent something of my own. When word got out how good Clarence was, everyone wanted to play with him. He started hanging out with James Burton [Elvis Presley’s guitarist] and listening to Django Reinhardt. Just as I couldn’t match Clarence, Clarence couldn’t match Django but in trying he came up with something more daring than he’d done before.

“About that same time, I heard Doc Watson, who was playing leads on acoustic guitar much like Clarence was. They were different because Doc came out of old-time mountain music, while

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Interesting life . Learning to love Blue Grass!