Home > Articles > The Tradition > Hall of Famers Unveiled

Hall of Famers Unveiled

Jimmy Martin

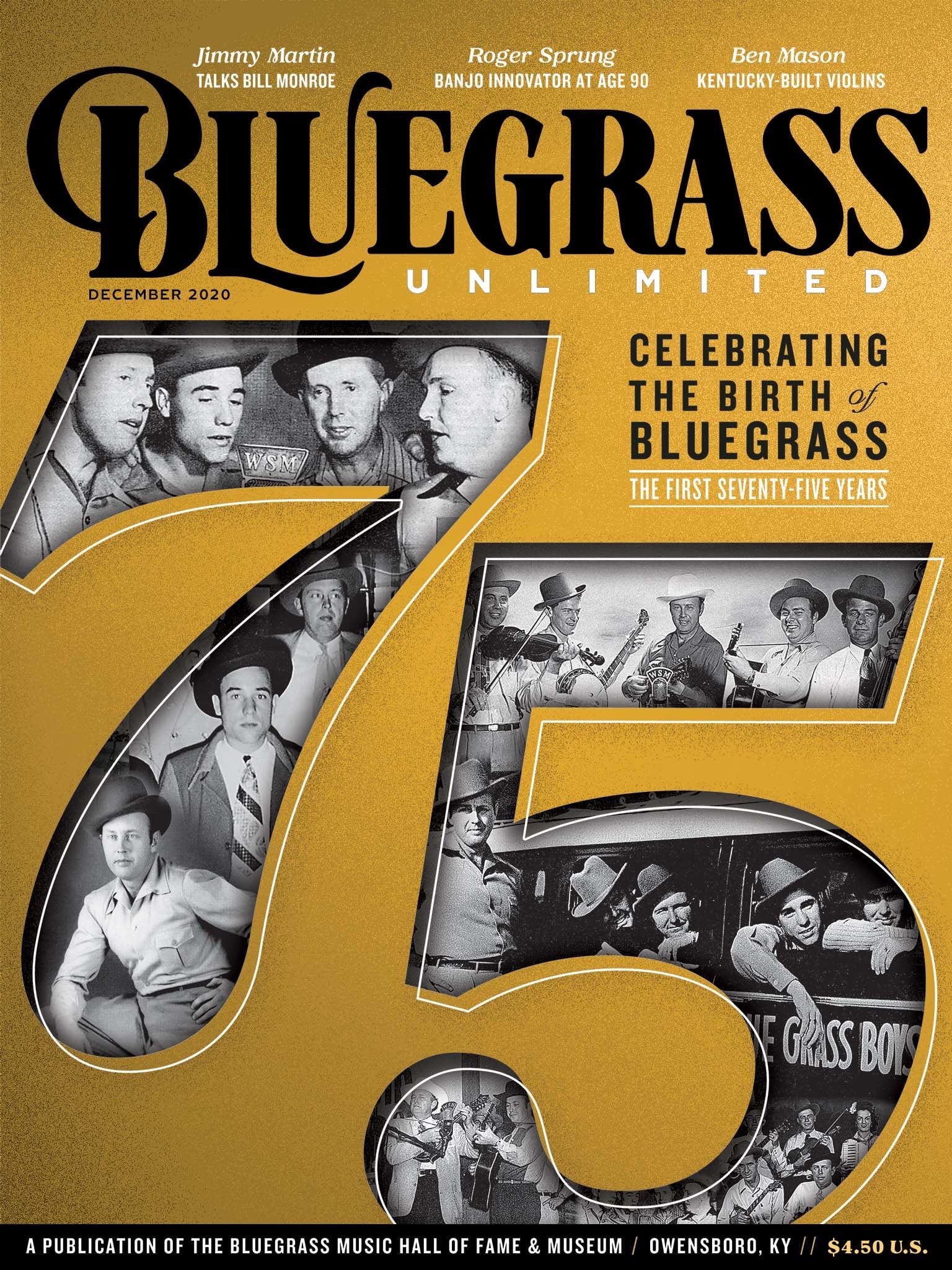

As we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the bluegrass genre, Bluegrass Unlimited magazine will look deep into what made those first-generation bluegrass artists tick.

At the magnificent and sprawling Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro, KY, the venue seeks to tell the story of bluegrass music by going deeper into the personalities of the music’s legends, adding to the impressive plaques that line the walls.

With a host of unique artists present as the bluegrass star ignited and formed in 1945 and continued to evolve into the 1940s and 1950s, there are a lot of stories to tell. This interview with IBMA Hall of Famer Jimmy Martin happened in 2004, about a year before his death in 2005. Even though he was dealing with chemotherapy and radiation treatments at the time, Martin was thinking clear, ready to talk and was his usual irascible, no-holds-barred self.

One reason why this interview was so successful, I believe, is that I am a West Virginia native who has dealt with old contrarian Appalachian men my whole life, in my family and otherwise. It paid off as Martin poured out his heart in this conversation. But, you also have to remember that pride and ego were present in both Monroe and Martin and that this is Martin’s side of the story. Still, tucked away in the bravado are some real nuggets of insight into both men.

This article with Martin plays out in three parts, from his hard time as a youth in rural Tennessee and his desire to meet Monroe to the feud between them after Martin went out on his own to the love that Martin had for Monroe until his death 15 years ago.

This interview originally appeared in the now-defunct Gritz magazine, a publication that did not survive the Great Recession of 2008. Still, somehow bluegrass legend Peter Rowan found it, read it and loved my interview with Martin, and he reminds me of it every time I see him.

“That was a most unusual Jimmy Martin interview that you did, because he talked about Bill Monroe like a psychiatrist, that Bill had built a barrier around himself,” said Rowan. “Like you said, the original bluegrass hard-core artists are like contrarians. And, you got some stuff out of Jimmy. It is very good. That is one of the most honest, heartfelt interviews as Jimmy Martin really opened up to you, man. Jimmy talked about Bill and about his understanding of Bill, and why Bill was so contrary to Jimmy Martin. Jimmy could be on the defensive and play the clown a lot, but Jimmy was also brilliant and was the real deal, as were all of those guys back then.”

The Path to Bill Monroe

Jimmy Martin had a hard childhood while growing up in the small town of Sneedville, located in the rolling hills of east Tennessee. Recently, in the summer of 2020 when I took a detour on the way home from acclaimed bluegrass musician Steve Gulley’s funeral service, I explored Sneedville and the surrounding area. First and foremost, it is beautiful country as that region of the Appalachian Mountains features one pristine farmland valley after another as well as the awesome watershed that is the Clinch River. Even now, Sneedville is out in the middle of nowhere, and those places can be hard to find in this day and age.

As for Jimmy’s youth, he did not get much of a formal education, and on top of that, he had a step-father that worked him a little bit too hard on the farm. Still, Martin developed a love for music as a youth that would not go away.

“I plowed corn one row at a time, and plowed two to turn the whole ground up with a turning plow,” said Jimmy Martin, when I interviewed him in 2004. “And, I plowed the whole farm up many a time just by myself. My folks are from West Virginia. My Dad died when I was four years old. My mother married my stepfather and he liked to work the heck out of me. I studied music since I was a little boy. I sung in quartets with my stepfather in churches and funerals. I learned all the parts of the quartets. I tried to get me a guitar, but my stepfather tried to keep me from getting one because he knew I was going to leave him because I wanted to play on the radio. And, the main job that I always wanted from the time I started until I finished was a job with Bill Monroe.”

One day, Martin made the trip to Nashville to see Monroe perform at the Grand Ole Opry. Afterwards, he took the bold step of approaching Monroe and basically asked the Father of Bluegrass for an audition. That may seem crazy, yet Martin came prepared like few others and he knew just what to do.

“It wasn’t too long after Lester (Flatt) and Earl (Scruggs) left Bill when I went down there to the Grand Ole Opry and tried out with him, not knowing at any time that I would get a job with him,” said Martin. “But I had his songs learned, and I knew how they went. I know about all of his songs. When I sung with him that night, Roy Acuff helped me a lot. I sang a song with Bill and told him how good I liked his music. Then, I sung two songs with him and played a fiddle tune with Chubby Wise. Roy Acuff stuck his head in the room, and said, ‘Bill, is that boy any kin to you?’ Bill said, ‘No, why Roy?’ He said, ‘He sure blends good with you.’”

The next thing Martin knew, he was asked to do a short tour with Monroe to see if he could handle life on the road.

“Bill said to me, ‘It’s hard traveling,’” said Martin. “I went with him a week and we encored big, two or three times a night on the show. He had Mac Wiseman with him, and he really didn’t need a guitar player and a singer. But, it seemed like the people enjoyed us real good. And, we got out of the bus and he asked me how I liked it. I said, ‘Pretty good.’ He said, ‘Do you think you can stand this hard traveling?’ The bus broke down two or three times and we had to push it that week. I said, ‘It’s a lot better than digging ditches and shoveling mud out of them, and plowing corn with one horse and sawing wood with a crosscut saw.’ Growing up, we never had a truck and never had a car. We had two horses and a sled when I was home. I said, ‘I think I can do the job. I think I like it better than hauling hay to the barn, and hauling manure from it.’”

Martin’s run with Monroe came after Flatt and Scruggs had left the band. Eventually, after joining the Blue Grass Boys in 1949, Martin would leave Monroe as well in 1954. That had to be hard on Monroe as his long-sought original sound had taken root and he was fronting some of the best bands he would ever have, yet those musicians left to make their own way, wanting their own names on the marquis.

Monroe was not happy about those personnel changes and hard feelings were formed. Band members come and go, but former band members who go on to become competing headliners in the tough music business is a whole other matter.

“Bill (got mad) with everybody,” said Martin. “He did that with Chubby Wise, too. He loved them, and the reason why he did things against them was because it was tearing his heart out because they were so damn good. They were good singers and good pickers. He didn’t have anybody to show music to when he had Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, Chubby Wise and Cedric Rainwater in his band. They all knew as much about it as he did. He just had to hang in there. You see, they changed his style when they went with him. There is no use in me talking and running my mouth about it. All bluegrass pickers that got ears and know music know that Bill Monroe, when he took a band in 1938 and went until 1946, his band changed 80 to 90 percent when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs went with him. It changed to Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs’ style, is what it did. It brought Bill in there to a different timing and a different sound completely. And you don’t have to take Jimmy Martin a blabbing his mouth, you can just get the records and listen to it.”

Grudged

Martin began to record successful records and eventually took on the mantle of the “King of Bluegrass.” Monroe, by many if not all accounts, got his revenge by keeping Martin from becoming a member of the Grand Ole Opry, which was a life-long dream for the kid from Sneedville.

“Oh yeah, I was nervous when I met Bill,” said Martin. “I was real nervous. He was my idol. He always was my idol. I still call him my idol. The only thing that started Bill Monroe shunning me, not speaking to me and doing things against me was when my records got hot.”

To Martin’s defense, record labels began to call him, wanting to record him as a solo act. In those days of the 1950s, record labels ruled the roost and turning one down was a serious decision to make.

“I left him when Decca Records, the label that he recorded for, and Columbia Records and RCA Victor all offered to record an album with me singing,” said Martin. “When I sung ‘Poison Love’ with Bill and they heard my voice, they wanted to record me. They said they would record me and I could stay on with him. So, I asked him about it and he was paying me and didn’t want me to record for anyone else because I think my albums would have sold real well. Everybody wanted to hear me, you know. I’d always front the show and sing a song before I came out with Bill, and they always liked what I sang, and Bill liked it, too.”

Soon, Martin decided to leave Monroe’s band and go out on his own. Facing Monroe with that news was no easy task.

“Oh yeah, I remember it as well as it was tomorrow,” said Martin. “I just came up and told him that I wanted to lay in my notice. He said, ‘Well, what have I done?’ I said, ‘You ain’t done nothing. If you don’t know, I’m not going to tell you.’ You see, he didn’t want me to record and I wanted to record. I was barely living, just making it by paying my hotel bills. I wasn’t getting ahead with no money or anything, so I decided to leave and worked my two week’s notice out. He said he still didn’t have anybody to replace me, so I worked another week. Again he said he didn’t have anybody, and I think I worked six or seven weeks more, trying to wait until he got somebody. Finally, he told me he wasn’t ever going to get nobody to take my place. And when it come time I said, ‘Well, I got to go. I got places where I’m going to try and get me a group and record, Bill.’ He still held to my hand for a long time and kept squeezing it. I said, ‘I hope you get somebody good to take my place to help you.’ And he told me, ‘I’ll never get nobody to take your place, Jimmy. I’d rather have you than anybody. If you get out there and can’t make it and you want you a job back just call me collect. I’ll send you the ticket to come back home.’”

Indignant attitudes developed between prideful men are not exactly a new phenomenon. It is as old as human history. One thing that needs to be understood is that Martin could give as good as he got and he could stir up antipathy and hard feelings with the best of them. His feuds with Sonny and Bobby Osborne as well as with Ricky Skaggs and others were legendary, and mostly one sided with Martin priming the pump. Those three individuals, however, and impressively, would heed Martin’s call to visit him on his death bed a year later. I’ll leave those men to tell that story.

As for Monroe and Martin, they never settled things as the years went by. The hard line between them became Martin not being asked to become a member of the Grand Ole Opry.

“After working at the Wheeling Jamboree, I moved to Nashville,” said Martin. “Every time I was down there at the Opry I encored on my own songs. The last time I was down there I encored on ‘Tennessee’ and ‘Sunny Side Of The Mountain.’ Stringbean and Ira Louvin came up to me and told me how good I sounded. Stringbean said, ‘Boy, you went over big. You tore ‘em up. You probably went over just a little too big. It might be a while before you’re ever back down here again.’”

While Martin played a few times on the historic music show, he was never asked to be a member of the Opry.

“(Then Opry manager Bud Wendell) never made me a member, so I’m not going to raise no fuss about it,” said Martin. “I think that I’ve done much better on account of not being a member of the Opry because the public aggravates me to death asking me ‘Why can’t I ever get to hear you on the Grand Ole Opry.’ All I say is, ‘I guess I never have got good enough.’ So, I feel like now, the Opry has helped me money-wise, but they’ve hurt my feelings for doing that. I think why they’ve done it is because of all kinds of jealousy of other musicians. So, I just feel proud that I bother them that much. The grudge has lasted because some of them down there are still grudged at me. Bill Monroe would turn his head and let on like he was trying to ignore you, thinking somebody was going to jerk him by the coattail and pull him around and say, ‘Here, speak to me.’ But I’m telling you, he ignored the best friend he ever had and ever would have. You’re talking to the best friend that Bill Monroe ever had. And, I loved him more than anything. I loved to stand and look at him. But he couldn’t stand for me being popular. That was it. I loved him. He just didn’t speak to his best friends. That’s it right there.”

Martin Loved Monroe

Make no mistake about it and never doubt it, as deep in his contrarian soul, Jimmy Martin went to his death bed loving Bill Monroe and the music he created.

“I told Bill Monroe, when he took me on, that I could sing baritone, lead, and tenor,” said Martin. “But, I couldn’t sing tenor as good as him, but I could sing tenor. When he hired a new man, I would help him learn the baritone part and then teach them Bill’s tunes. When Bill was off, why we’d stay in the Tulane Hotel, me and Rudy Lyle, and teach the new man all the tunes before Bill even got there. And, usually we’d ride along in the car and a baritone part that Bill would have that the new man couldn’t get to it, or bass part, I’d hum it to him and show him how it’s done. And, Bill would say, ‘Just get it like Jimmy’s a showing you and it’ll work just right.’ People didn’t know that. They never have learned that. It’s never been out.”

One of the most fascinating images provided by Martin is of him and Monroe woodshedding together, trying to perfect their sound.

“Bill and me would sit down a lot of times in busses and rooms and just pick by ourselves and do different licks on the mandolin,” said Martin. “You see, that’s how he done them little extra licks. He used to just stand straight and play the mandolin. When I got with him he kind of got on his tip-toes and jumped up and down a little bit. But he couldn’t stand that jumping beside of him. I was doing it, too.”

Martin loved it when Monroe was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, adding to his induction into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

“Let him get in all the hall of fame’s he can,” said Martin. “Stand him right up there. Because I told him one time, I said, ‘Bill, you play rock and roll mandolin and you don’t know it.’ He said, ‘I don’t play that dang rock and roll.’ Be sure and put that in there, now. I said, ‘You don’t know that you play rock and roll mandolin? The way you chunka-chunk-chunka-chunka (making the sounds of a rocking mandolin rhythm).’ I said, ‘Listen to rock and roll blues and then listen to ‘Brakemen’s Blues.’ Why, you’re rocking on down the line, Bill. And, when you kick off that ‘Muleskinner Blues,’ that’s a kick off of a rock and roll song as I’ve ever heard.’ And he said, ‘I don’t play that dang rock and roll.’ I said, (laughing) ‘Ok, Bill.’ Yeah, he did, and hooray for it. That’s the reason why he is different and nobody else can play it. He had it all. When they think they’re playing that mandolin like Bill Monroe, they better let me get up there with my guitar and I’ll show them they’re not. There ain’t nobody that can touch him.”

Finally, Martin left us with some advice about playing bluegrass music. Coming from a true bluegrass master and hall of famer who folks like Tony Rice say was the best rhythm guitarist ever in the genre; these are words to be considered.

“Your band has to play together,” said Martin. “It has to come together just like a ballgame. You have to match your music just like you match your singing. I’ll tell you one man that could tell you that right quick and that’d be Earl Scruggs. They kept their act together and everyone knew when to take a break and when not to. Not on account of Lester, but on account of Earl Scruggs. He was the boss over there. And there can’t be five guys go together and say, ‘I’ll get to play like I want to.’ There’s got to be somebody that knows how to sound in there.”

The goal, as was made true by the first generation of bluegrass, is to make your own unique sound.

“Now, bluegrass is sounding all alike,” said Martin. “That’s the reason why, when you play my records, you know its Jimmy Martin. When they play Ralph Stanley’s records, they know it is Ralph Stanley. When they play Mac Wiseman, they know it is Mac Wiseman. When they play the Osborne Brothers, they know it is the Osborne Brothers. When they play Don Reno and Red Smiley, they know it is them. Nowadays, you throw the rest of them in a barrel and they come out and you don’t know which one’s out. Go and play your records. It’s not there. The good old hard feeling of playing the tune of a song is out. And, what is there in a song but the tune? It’s what you’re supposed to play. That tells the rights of a song. Not to get in there and try and make a mockery out of it.”