Ground Zero for Traditional Bluegrass

For thoroughbred racing, it’s the Kentucky Derby. Golf has the Masters. The greatest spectacle in racing? The Indianapolis 500.

Traditional bluegrass? That’s Bean Blossom.

Only a handful of bluegrass festivals have accomplished as much and lasted so long to have achieved first-name status among the bluegrass and old-time country faithful. Names like Galax, Winfield, Telluride. To hear each, condensed to its geographic essence, evokes instantaneous recognition and perspective in bluegrass fans. Against that backdrop, Bean Blossom’s reputation is so potent, American Songwriter magazine just named it the #1 bluegrass festival in America.

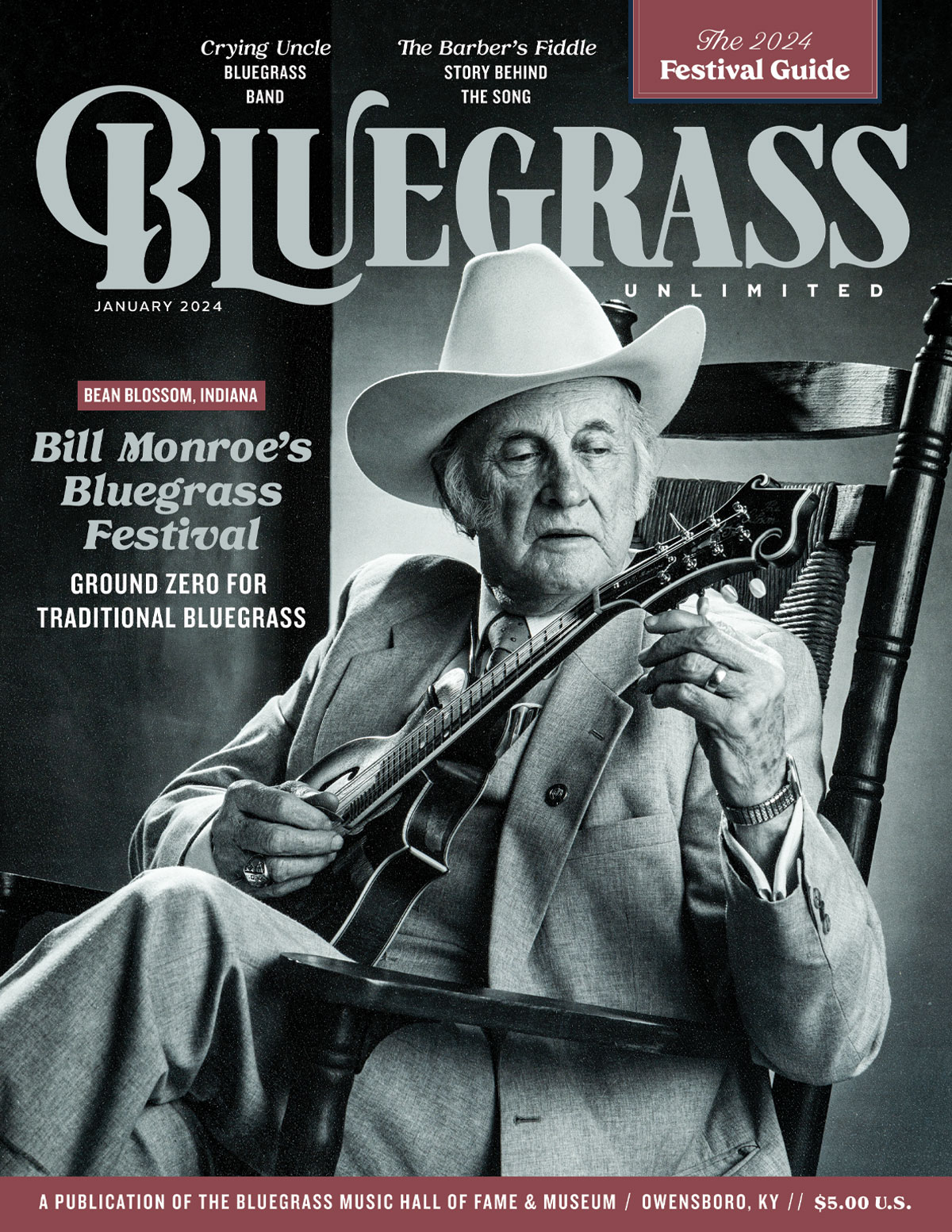

Known formally as Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Festival, the 59-year-old, four-day, undiluted, deep-rooted traditional bluegrass event held every June in Bean Blossom, Indiana, truly is “Ground Zero,” as Sam Bush called it. The name is so universally recognized that when I was graciously invited to sit-in with the house band on stage at one of Tokyo’s bluegrass clubs, I mentioned that I lived just 45 minutes from Bean Blossom and even the audience that couldn’t understand English knew that name enough to applaud open-heartedly.

Big Mon Buys The Farm

The limestone spring-fed roots of Bean Blossom go back to an amateur jam called the Brown County Jamboree at a local filing station/lunch counter owned by Dan Jones. A Dollar General occupies that space now. Local musicians would jam there, and by 1941, it had evolved into a popular local tent show with a stage and PA system. Monroe knew Indiana well through his travels from Kentucky to Whiting and Gary, and during his tours with the band often would stop by Bean Blossom to participate.

The Jamboree’s growing success led to the decision to build a permanent, stand-alone music venue. The October 23, 1941 edition of the Brown County Democrat reported: “Plans for a large permanent building to be used for the Brown County Jamboree in Beanblossom (sic) to replace the tent which is now being used have been completed… It is to be located on the land owned by Francis Rund just north of Beanblossom where the tent which houses the jamboree now stands.”

Monroe, seeing the potential to bring in national touring acts and having a home base so centrally located, bought the completed building and surrounding farmland in 1952. Brother Birch arrived to run the farming operation, giving local kids like current owner Rex Voils the chance to earn a few bucks weed whacking the property before shows.

“All the kids around here worked for Bill Monroe, who we all called the old country star. We didn’t know about bluegrass in the 1970s. I’m from Bean Blossom so before his festivals we would work with Birch and we would weed whack, and clean up the trash, like around the old barn here. That’s how I got to know the Monroes—on a working end, not a music end. I’m not a musician, I can’t even tune the radio in my truck,” Voils told Bluegrass Unlimited. “And (Monroe would) come up to the park when we were weed whacking. He’d come in, take his hat off, put on another hat, take his jacket off, roll up his sleeves, and he’d go after those weeds with a scythe like he was killing snakes. And we boys would go, ‘The old man’s crazy!’ But he was just showing us that he could still do the work.”

After the purchase, Monroe continued the Sunday evening jam session tradition using the now-established Brown County Jamboree moniker. Soon, his peers on the Grand Ole Opry and other touring acts made it a regular stop.

Encouraged by that success, Monroe hosted Bean Blossom’s first true bluegrass festival in 1967. Monroe disliked the word “festival” because he thought it evoked a counter-culture image. In addition, other multi-day outdoor music events were using that term and Monroe, being Monroe, felt he needed something unique. So his first festival became the “Big Blue Grass Celebration,” a two-day event held June 24-25. Featuring Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, Benny Martin and Rudy Lyle, Hylo Brown and, most assuredly, Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, it was an instant hit. In just a year, the Bean Blossom “Celebration” grew to 10,000 visitors over three days. By 1969, the West Coast’s “Summer of Love,” the event became “Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Festival,” conceding the need to use current terminology. The four-day experiment in sleep deprivation, hand muscle overexertion, and campfire smoke exposure included instrumental contests, square dances, the evening Sunset Jam, workshops from the leading pros, and many other features that would go on to become pillars of the Bean Blossom experience and history. Monroe had set a paradigm for bluegrass festivals, domestic and foreign, that many follow today. And that financial success allowed Bean Blossom to draw every prominent artist in bluegrass, along with rising stars like the Good Ol’ Persons and countless others. Playing Bean Blossom was—and remains to this day—a bluegrass badge of honor.

Flush with success, Mr. Monroe would remain the owner and impresario of the festival and campground until his death in 1996, when ownership passed to his son, James Monroe. After a few years, James sold the campground and its profitable intellectual property to former Blue Grass Boy and area resident Dwight Dillman, whose family has been an integral part of the Midwest’s bluegrass scene for decades.

Dillman, who politely declined to be interviewed for this article out of his deep respect for current owner and close friend, Rex Voils, brilliantly leveraged the naming rights he’d acquired with the deed and renamed the property “Bill Monroe’s Music Park and Campground.” Rex Voils added the new modern bathrooms and laundry. The museum was built by Bill and James Monroe in 1992 and it was remodeled by the Voils.

And in a revolutionary move to better utilize his venue’s untapped economic potential, Dillman cautiously and respectfully departed from Big Mon’s original vision to expand the park’s use beyond bluegrass to include new annual music festivals and other events.

“Dwight Dillman did a great job running this place for 18 years,” Voils explained. “He saved (the park) from becoming a subdivision. And now we’ve been running it for six years, and we hope we can keep going on. Dwight had the same attitude, and he was a Blue Grass Boy. He wanted to keep it bluegrass, which is why we get along so well. He knows it’s going to stay bluegrass. And Dwight was picky, he could have sold the property off many times. But he sold it to us. And to this day, I’ll call Dwight, and we’ll ask him ‘What do you think about this?’ It’s like one big family. And that’s what we’re doing. We’re caretakers for all that he had. He was a fantastic carekeeper, and he still comes down to the festival every year.”

West Meets East

It was a warm Indiana June day in 1983 when John Reischman caught his first glimpse of Bean Blossom. He, along with Good Ol’ Persons bandmates Kathy Kallick and others, were rolling cross-country in a borrowed station wagon for the Bay Area bluegrass band’s first national tour. “It had wrong size tires on it, and we kept having blow-outs,” recalled Reischman, one of the architects of West Coast bluegrass. Playing Monroe’s festival was the shimmering jewel in the tour’s crown.

“It was an interesting time. We had just recorded I Can’t Stand to Ramble,” Reischman recalled, and the tour was launched to promote the new record. The then-obscure West Coast band’s getting booked at the legendary Bean Blossom festival happened through Kallick’s relationship with mandolinist Butch Waller. She had gotten to know Monroe a little bit through Butch, Reischman said, and that connection led to the booking.

“Our first set was somewhat disorganized. I think the main sound system hadn’t arrived yet, so this would have been mid-week, maybe. So they set up this interim sound system with three mics, which was okay since we were kind of used to having only a couple microphones for our pizza parlor gigs,” he noted.

Reischman, who, like Monroe, owns a legendary Loar-signed Gibson F-5 mandolin, had met Big Mon the year before when both artists were booked at California’s popular Grass Valley festival. “We got to jam a bit in a hotel room. We were sitting there playing mandolins together. I showed him mine (Loar) and we swapped mandolins for a while. So that was pretty great. But I’m not sure he even remembered me at Bean Blossom,” John recalled.

Once settled in, their connection grew. “I had the Loar at the time, and I asked (Monroe) if he’d tune it (in cross-tuning) and play it on ‘Get Up John’ on stage. So I stuck it up on stage and he played it that set. It was pretty amazing,” he said.

Like most visitors, Reischman took the opportunity to take in the rich history and legacy of having hosted some of the greatest moments in live bluegrass. “I was impressed because it’s such a historical place. It was cool to see ‘Back Home In Indiana’ on the stage. And all the autographs—Jimmy Martin, Ralph Stanley, and more—on the wall behind the stage. Being in the campground, seeing the shows, checking out the jam sessions. There were so many cool bands there. I think Monroe playing my mandolin on stage, and just getting to play there—it was kind of the culmination of this arduous trip.”

Tsunami of Applause

You can’t tell the full story of Bean Blossom’s historic, global impact on bluegrass without including the experiences of the first Japanese bluegrass band, Bluegrass 45, who visited the festival for the first time in 1971.

Japanese bluegrass legend Toshio Watanabe explained his first trip, crossing 14 time zones and the International Date Line to arrive in rural Indiana: “My first Bean Blossom experience was as a member of Bluegrass 45 in 1971. Not only did I have no prior knowledge of the event, but it was my first time in a foreign country, the United States. I saw and heard many of my heroes and stars that I had only seen on record all at once. I was so surprised and excited that I don’t remember most of it. After that, I visited many times with my family as well as many bluegrass friends who visited Bean Blossom from Japan. Of course Bill Monroe, Birch Monroe, Jim Peva and his family … Their warm welcomes for us are a treasure of my musical life.”

Mandolin master Shin Akimoto of Japan’s Moonshiner bluegrass magazine first visited Bean Blossom in 1982 on a tour organized by B.O.M. Service, a bluegrass mail-order store started by Toshio & Saburo Watanabe.

“I remember being greeted at the gate by Bill Monroe in his regular clothes. We spent time at Jim Peva’s campsite, where he was serving as a bluegrass ambassador. His daughter Kathy cooked us many hamburgers. Kenny Baker stopped by the campsite and played a few fiddle tunes for us. I remember how excited I was when I played on stage with the members of the band that accompanied me, and we were greeted with a tsunami of rousing applause.”

Akimoto-san also remembers enjoying playing with Bill Monroe at the legendary Sunset Jam. “The fiddling for background music at the Sunday services with the pastors was beautiful. Since Bluegrass 45 played at Bean Blossom in 1971, the place has been very welcoming to Japanese bluegrass people,” he said with respect and appreciation. And in keeping with the festival’s impact on Japanese fans, Shin directs the Takarazuka Bluegrass Festival, which now has more than half a century of history. Started in 1977, it “built a bridge between Japanese and American bluegrass,” he said with pride.

Building a New Tradition

For Bean Blossom native Rex Voils and his family, owning and operating the historic bluegrass park isn’t just a moneymaking operation. They see themselves as rebuilding a local institution for the future to ensure that the decades of bluegrass music history and tradition flourishing there never fade behind time’s unforgiving walls.

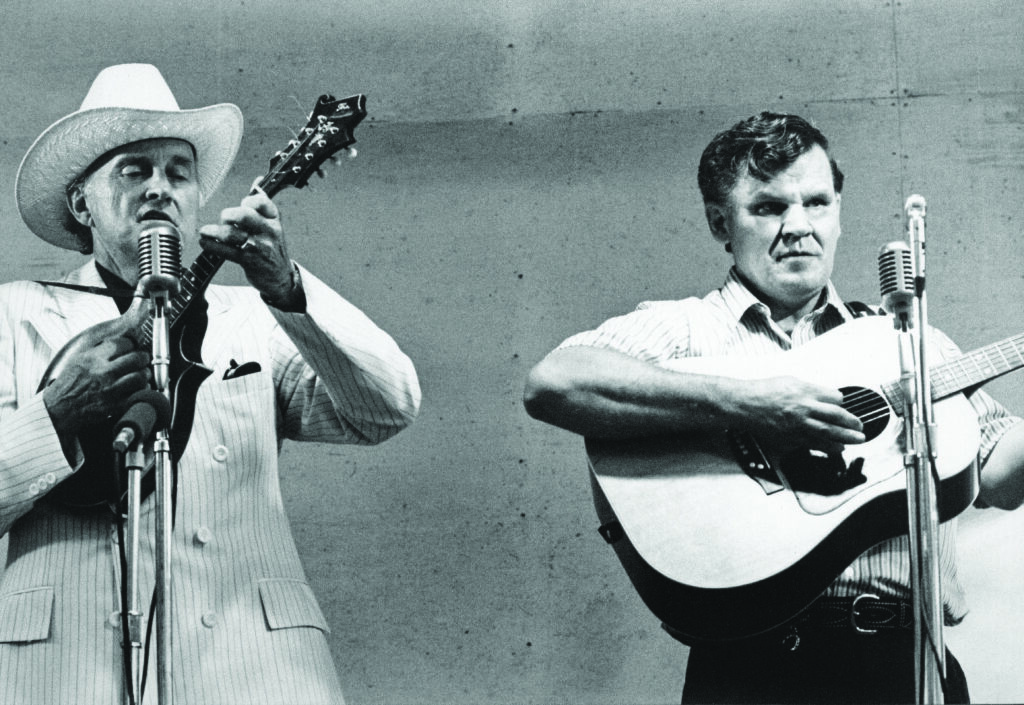

“Sam (Bush) said, ‘Thanks for inviting me to Ground Zero’ the first time he was invited back to perform under the Voils family management. And he has been coming up here from Bowling Green since he was a kid, so for him, it really is Ground Zero. That’s what you take in when you come here. The tradition, the Jimmy Martins, artists from Roy Acuff to Billy Strings, so many famous musicians, Bobby and Sonny (Osborne), Jimmy and Jesse (McReynolds). That’s what Bean Blossom is. You’ve got the museum and hall of fame, you’ve got this property that Mr. Monroe walked on and ran cattle. He loved this place because the glaciers ended here (leaving Brown County very hilly). He loved to fox hunt here.”

But as the sidebar article explains, the Voils family has had to adapt to changing market conditions, requiring their creativity and passion to create new revenue streams. One big part of that is leveraging the park’s history and Monroe’s name and likeness to build up its appeal to bluegrass fans and beyond.

“We started our history hayrides every Saturday, and if we have 16 airbnb cabins booked, we might have 60 people on a hayride in a weekend. We take them through the museum and explain what’s there and tell them about the history of bluegrass. We take them to Mr. Monroe house and tell them lots of little stories about the park and its history,” he explained.

“We’re trying to bring the youth back, and it’s starting to work. But we still promote (our) other festivals, so with the Airbnbs, the seasonal campers, that’s what’s helping us keep the park open and help traditional bluegrass survive. And it’s working. We had 500 or 600 more people here for the June festival this year than last year,” Voils added.

Asked what he most wanted Bluegrass Unlimited readers to know, Voils responded without hesitation. “Here’s the thing: our June festival is the last traditional bluegrass festival in the country. We don’t mix in country, rock, or anything else. When people come to our festival in June, they’re going to hear traditional bluegrass. They’re not going to hear rock or country, or the long-haired hippie crowd, which I like,” Voils said with a grin.’

“We are going to keep the June festival traditional. If you want traditional bluegrass music, the June festival at Bean Blossom is where you want be.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I have worked at bluegrass festivals for close to fifty years.Bean Blossom is A very special place.Everyone should visit .Bill Monroe’s museum alone is worth the visit.There is more history of bluegrass and country music there than any where else.Put the park on your bucket list