Home > Articles > The Archives > Frank Wakefield

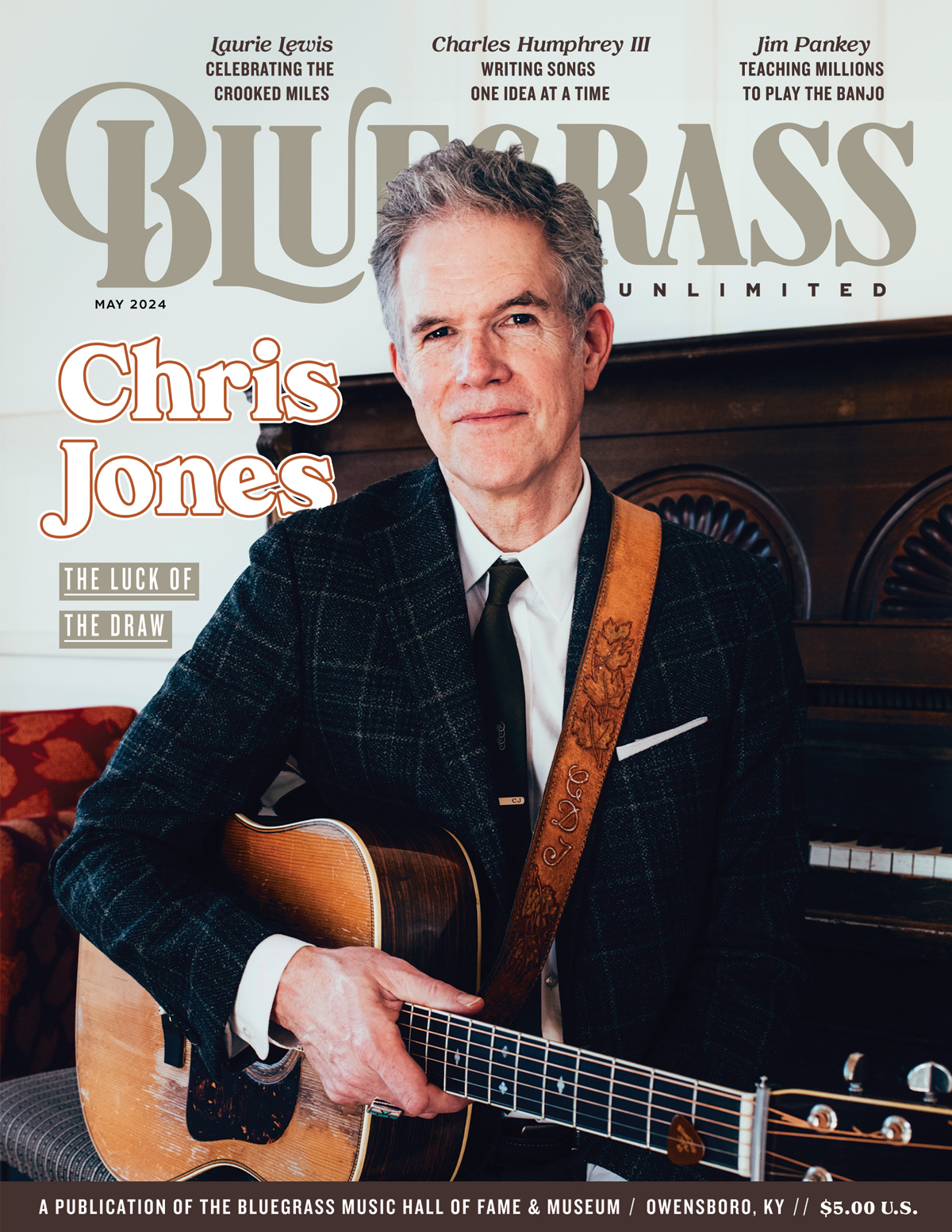

Frank Wakefield

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1983, Volume 18, Number 1

In the often imitative annals of bluegrass music, Frank Wakefield is an original. He is a living legend among mandolin players for his technical virtuosity. He is well known to bluegrass aficionados as the composer or co- composer of such songs as “Leave Well Enough Alone” and “New Camptown Races” and has five solo bluegrass albums to his credit. Still, you might be hard pressed to find two out of ten fans who could agree on a label for his music or whether Frank Wakefield is a genius, a fool, or a maniac. It’s a case of the blind- men and the elephant.

Critics tend to love him and are always amazed by the depth of his composing and playing talents after evaluating the more bizarre aspects of his shows, rap, and lifestyle in their reviews. More often than not their message is, “This guy is nuts, but he sure can pick!”

His performances are a crazy quilt of bluegrass singing and playing, new mandolin music, and medicine show/backwoods humor. He goes after an audience relentlessly with both music and patter, outrageously selling his act like a bull in a china shop. Reviewers tend to dwell on this aspect of his show detailing his instances of “backin’ talkwards,” (“Goodbye, pleased to meet me,” “Thank me very much for giving you that big hand ’cause you’re the best mandolin player in the world,”) and telling of rather obscure tales, (“I was playing my music with that big sympathy orchestra, they play a lot of Baytoe and Shevosky, none of that country music like Twidway Connie or Sammy Davis Davis. That director kept a’ shakin’ that stick at me!” “This is the best mandolin in the world and I took off the strings one time and baked it in the oven.”) It’s a feast of non sequiturs that offers, sadly, an easier newspaper story than the brilliant music that punctuates the patter.

Musically, Frank Wakefield is a bit of a chameleon. Most readers probably identify him with bluegrass music and Bill Monroe-esque mandolin playing. While certainly true at the beginnings of his career in the early 1950s, he has since played in a variety of musical situations, bluegrass-oriented to be sure, but with connections to city folk revival, rock, and most recently and importantly, classical music. The music he performs on stage today is a hybrid of it all. There is also his own new music, some of it composed for solo mandolin, and it’s a far cry from bluegrass as we know it. In it you can hear echoes of fiddle tunes from the Tennessee hills and glimpse bits of the high, lonesome sound, but it is the sounds reminiscent of Bach or Beethoven that are most impressive.

It’s all slightly unsettling. Here’s this outrageous, outgoing, shuck ’n’ jive, hillbilly rube, (Frank plays his role to the hilt on stage and in interviews), writing and playing this demanding, sensitive and beautiful music. Where does it come from? He swears he has never listened to classical music and half-jokingly suggests that he may be the reincarnated spirit of one of the past classical masters. When pressed on the subject he will only add, “I created this kind of music so that I’d be different, so that I wouldn’t be lost in the shuffle and be just another mandolin player.” Wherever the music comes from, it is amazing by any measure, and, bluegrass audiences love it.

Frank, born Franklin Delano Roosevelt Wakefield in 1935, hails from Emory Gap, Tennessee, a tiny town near Knoxville. His family was quite large, ten sisters and one brother, and all were musical, at least to the point of singing folk and church songs around the house. “I remember my mother used to sing ‘Little Birdie.’ That was her name, Birdie.” He also remembers singing songs like “What a Friend We Have in Jesus” and “Washed in the Blood of the Lamb.”

Like so many rural folks in the thirties, a major link with the outside world for the Wakefields was the radio. Young Frank remembers listening to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM from Nashville as well as WCKY from Cincinnati. He heard Opry stars like Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe on WSM and Wayne Raney and Lonnie Glosson on WCKY.

His first contact with a musical instrument was a disappointing fling at age six with the “talking harmonica.” “On these radio stations they’d always announce ‘talking harmonicas. Send $2.98 and you can make this harmonica talk like we do.’ It didn’t ever talk for me, so I started playing the guitar.”

He describes his childhood as fairly typical for the time and place he grew up. His memories are of a barefoot boy spending summer days fishing and playing softball. “I was a windmill pitcher.” He never mentions poverty but it must certainly have been a factor in his development as any family with twelve children in the middle of the Great Depression, in the woods of Tennessee, could not have had an easy time of it. Education was certainly not stressed and Frank quit school after the third grade.

As he continued learning to play the guitar he was soon good enough to accompany his sisters and friends as they sang. He was also exposed at this time to religious music at local Baptist churches and Churches of God with both white and black congregations. He recalls some experiences at Pentecostal “snake handling” churches. “It was about the same as the Church of God except that they believed that you could drink poison or handle a snake and let it bite you and you wouldn’t be hurt. I didn’t believe that at all, I just played the music and let them scare each other to death with snakes.”

By his early teens Frank had become quite proficient on the guitar. As he met and played with other musicians, he noticed that everyone seemed to be a guitar player. As he began to take music more seriously it occurred to him that if he were to excel and be noticed he’d have to do it on another instrument. “I chose the mandolin to be different.” That idea of being different became important as both a means and an end to being successful.

Frank’s first mandolin was a less than perfect $2.00 “tater-bug” (round- back) that he got when he was about sixteen. It was so bad, he says, “It’d been a shame to put a name on it even if it had one. At first I played just a tremolo style, like the Monroe Brothers, with fiddle tunes and old-time songs.” It wasn’t long before he discovered bluegrass and, inspired by the likes of Bill Monroe and Jesse McReynolds, his progress was swift. He began learning their licks and solos in preparation to becoming a bluegrass mandolin player.

It was during this time that Frank began writing music. By age eighteen he’d recorded two of his compositions for the Wayside label, “New Camptown Races,” now a bluegrass mandolin standard, and the vocal which he co-wrote, “Leave Well Enough Alone.”

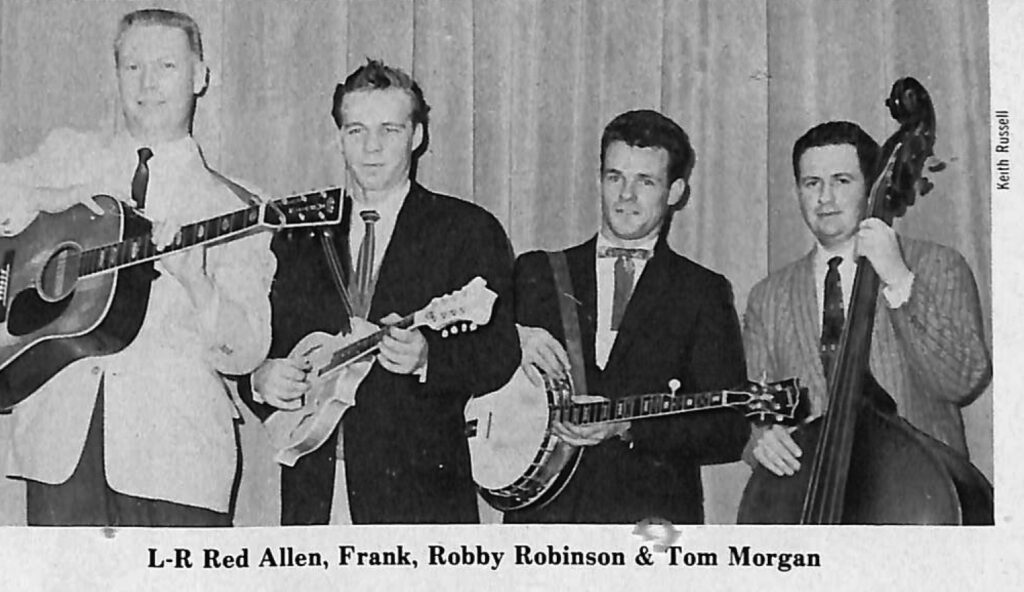

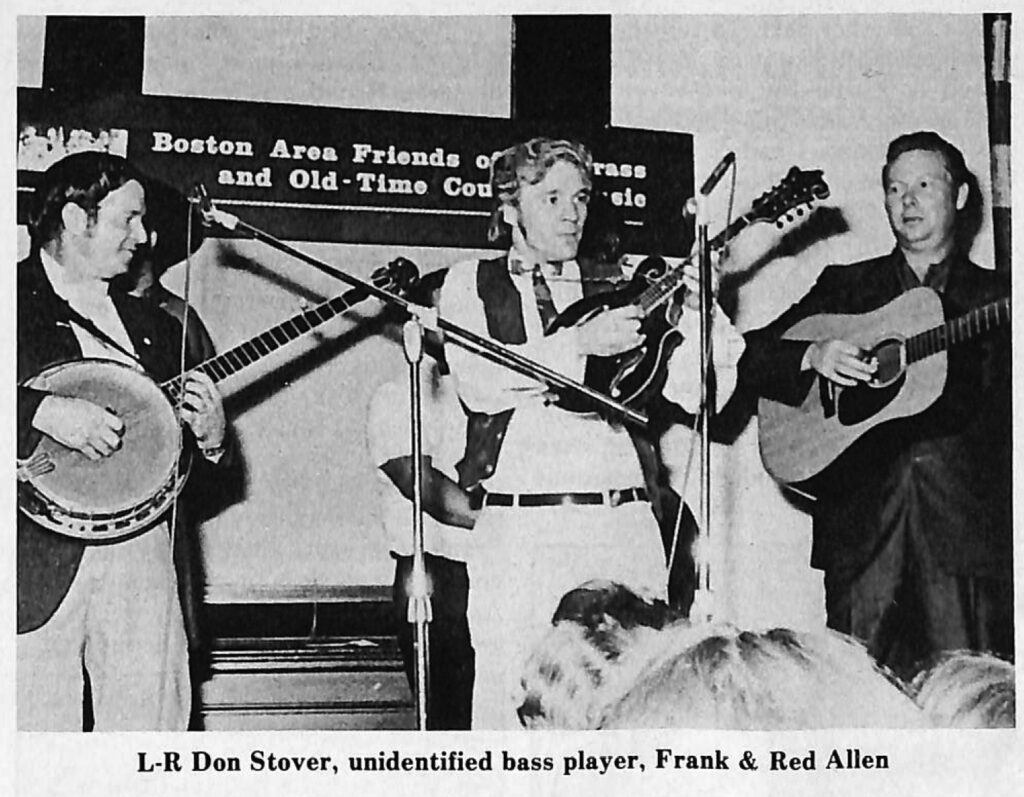

Soon after his first recording sessions Frank moved from Tennessee to Ohio where he met Red Allen. Together they were members of a band called the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys. Around this same time Frank had his hands annointed and prayed for by one Brother Stacey in Fairborn, Ohio.

Frank continued to perfect his approach to bluegrass mandolin while working with Red Allen in Dayton, Ohio. Bill Monroe became Frank’s idol and his near obsession with the father of bluegrass’ playing led him to a technical ability where, many have said, he could ‘“out Monroe Bill Monroe.” The young Wakefield was rapidly developing into a new and exciting bluegrass mandolin talent. And his original work on “New Camptown Races,” (a hot, fast, and difficult melody in the unheard of key of Bb) marked him as a kid to watch. Unfortunately, any fame he enjoyed was on an incredibly limited level and it was many years before his talents were known outside of a small group of Ohio fans.

Frank remembers with bittersweet memory one of his first meetings with idol Monroe. “Bill told me, ‘You can do me as good, or near as good as I can. Now you’ve got to go out and find your own style.’ That helped me toward what I’m doing today.” Once he got the Monroe approach down, he struck out in a million directions at once, always pushing the limits of the accepted norm, striving to be the best. From these beginnings he earned a reputation as a mover and shaker, aware of tradition and convention yet constantly agitating for change according to his own dreams and concepts.

It’s difficult to trace the actual beginnings of Frank’s unusual technical and compositional experiments since no records exist which accurately detail early developments. To hear him tell it he began bending the rules in the early 1950s. At first he became enamored of the possibilities of expanding harmonically the standard folk and bluegrass song fare he was performing nightly. This involved substituting more complex chord progressions for the well known and simpler two and three chord forms. (A recent recorded example of this is “Nilent Sight,” a reworking of “Silent Night,” from his “End of the Rainbow” (Bay 214) LP.) He was also doing this with his own compositions by adding new chords and sounds. “Leave Well Enough Alone” with its use of the two minor chord (‘A’ minor in the key of ‘G’) is a good example of a tune written during this period. It was re-recorded for “Frank Wakefield” (Rounder 0007).

Though he’d not yet begun composing his beautiful solo mandolin pieces or his “classical” band pieces, he was developing unusual picking techniques and adapting them to bluegrass mandolin playing. He of course used the cross- picking technique pioneered by Jesse McReynolds as well as developing other techniques unique to him. One involves holding the pick with his first finger and thumb while plucking other strings with his second and third fingers. This way he could play double or triple stops and independently moving lines on the mandolin. In the midst of fast tunes he’d use this technique to let sounds ring out and sustain. Since that time it has evolved into a highly complex technique of drone strings, multiple stops, and moving lines.

He also experimented with unorthodox mandolin tunings inspired by Monroe’s “Get Up John.” Two interesting later examples of this can be heard on “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player #2 (Rounder 0007) and on “Black Mountain Rag” from David Grisman s “Early Dawg” (Sugar Hill SH 3713).

This is not to say that Frank turned his back on straight bluegrass mandolin playing. Quite the contrary is true. He used these techniques within a bluegrass framework. They grew naturally out of the need to learn and expand. By all accounts he was an incredibly hot young player.

Throughout the late 1950s Frank honed his craft with a variety of different bands traveling a circuit from Dayton to Detroit playing loud, tough bars. While the experience of working to be heard above the din of a Friday night crowd may have led him to develop a strong picking hand, it did not encourage a choir boy lifestyle. The late night goings on, especially the drinking, would eventually take their toll on Frank as they have on so many other bluegrass performers working night after night under difficult conditions for even more difficult pay.

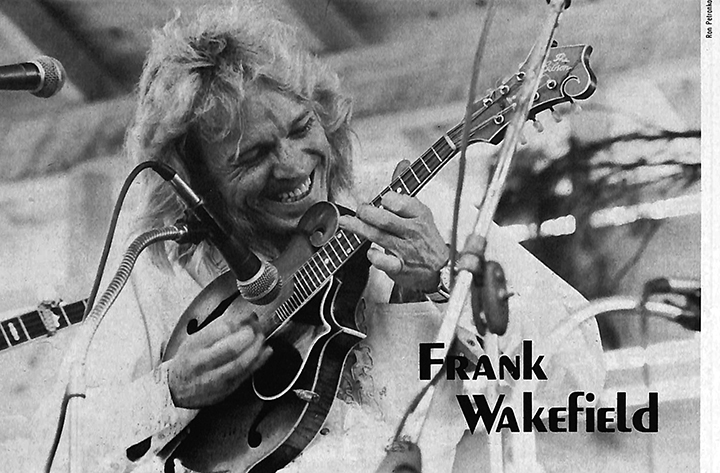

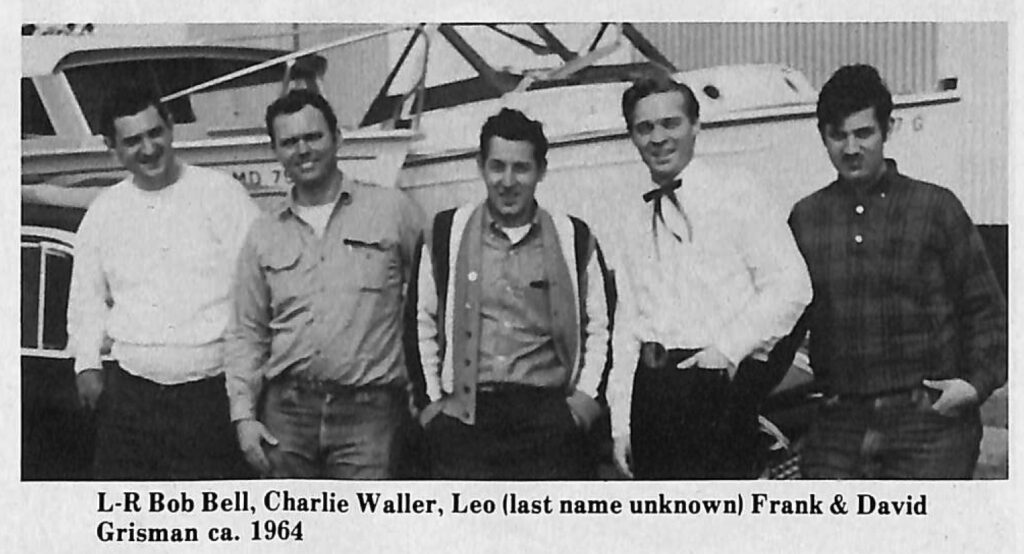

In 1959 Frank returned to working with Red Allen, this time in the Washington, D.C. area, though he continued working off and on with other bands. Eventually he met up with a teenaged, mandolin crazed, David Grisman who would subsequently produce the 1964 classic “Red Allen, Frank Wakefield and the Kentuckians” for Folkways Records. Grisman, who was inspired and taught by Wakefield, remembers, “In 1961 Ralph Rinzler took me to the New River Ranch in Rising Sun, Maryland and I heard both Bill Monroe and Frank for the first time, on the same day! Frank was with a band called the Franklin County Ramblers and they opened the show. He made me believe that all bluegrass mandolin players were fantastic. About a year later I hitchhiked down to Washington, D.C. during my high school Easter recess and saw Frank with Red Allen. I couldn’t believe the sounds he was getting out of the mandolin. He was a proponent of Bill Monroe’s style, but he departed from it to create his own. Frank was my big influence and he taught me about Bill Monroe.” Grisman later said that “Frank Wakefield split the bluegrass atom.”

With the release of the Folkways album, Wakefield got his first shot at widespread exposure. It gave him a certain degree of legitimacy that he’d previously not obtained and helped establish him as a wild extension of the bluegrass mandolin continuity that began with Monroe and continued with McReynolds and others. Frank eventually passed some of this fire onto the young Grisman and inspired David, as Monroe had done with him, to “create his own style.” This influence is especially evident on Grisman’s earliest recordings chronicled on “Early Dawg” (Sugar Hill 3713). You can hear Monroe through Wakefield’s ears and Wakefield through Grisman’s. It’s an exceptional study in the family tree of bluegrass mandolin. (This recording also shows some great examples of Grisman’s own bluegrass style heard later when he played mandolin for Red Allen.) David also was active in the successful effort to book Frank, Red, and the Kentuckians into Carniegie Hall in the fall of 1963.

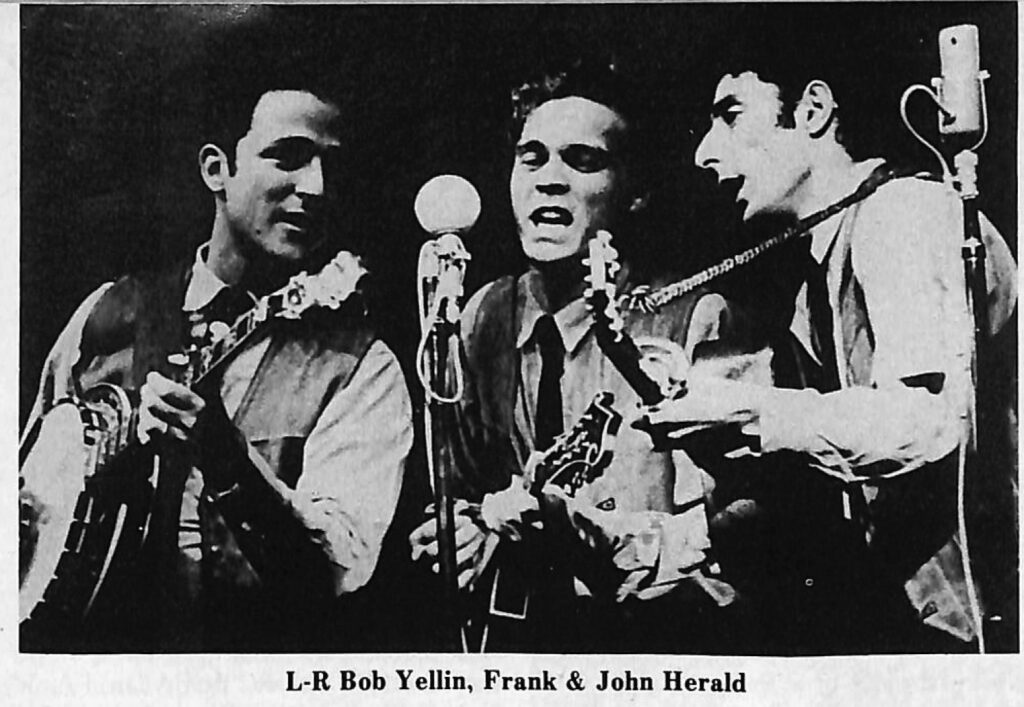

In 1964 Frank and Red Allen split once again and Frank joined the Greenbriar Boys. The Greenbriars were basically a “city billy” group that played a mixture of folk, bluegrass, and pop music. Frank contributed a great deal to the band vocally and instrumentally and was also a guiding force with arrangments and compositions. “Better Late Than Never” (Vanguard VSD 79223) shows off two of Frank’s arrangements, “Different Drum” and “Shackles and Chains,” both of which feature his characteristic use of substitute chords. Two of his vocal contributions, “High Muddy Waters” and “The Train That I Ride,” and one of his instrumentals, “Morning Train,” are also included. (It’s interesting to note that the Stone Poneys, Linda Ronstadt’s first band, used “High Muddy Waters” and “Different Drum” as the two sides of their first single, which turned out to be a huge hit. The arrangements of both tunes are virtually identical to the Wakefield/Greenbriar versions except for minor additions and the use of electric instruments and drums.)

With the Greenbriars, many of Frank’s modern bluegrass ideas were for the first time being performed on record and in concert. The band was quite popular, especially on the college folk music circuit. It was a case of the right combination of audience and ideas. Frank’s innovations fit well into the Greenbriar repertoire.

During his first year with the Greenbriar Boys, Frank was very seriously injured in an automobile accident. He’d been driving all night from New York and fell asleep at the wheel near Hyattsville, Maryland. At the time of the accident, he was only minutes from home. Head injuries put Frank into a coma that lasted a month. When he finally regained consciousness, he found that his vision and hearing had been affected, only temporarily it turned out, by the mishap. The trauma of the crash and recovery left Frank with serious doubts as to whether he would ever be able to play mandolin again. It was a very difficult time of physical problems and psychological doubts. “At the time, I thought I couldn’t play anymore. But, it turned out that that was not the case. I guess I was just worried by it all then.” Gradually he regained his strength and confidence and returned to performing with the Greenbriar Boys, continuing with the band until 1968 when he embarked on a solo career.

At about this same time, Frank’s solo mandolin pieces began taking shape. He swears that he’s never listened to classical music in his life and that, once again, his motivation for writing and performing these tunes was to “create something different.” He says, “I was always good at writing bluegrass and country songs and I thought I’d written enough of them for awhile. I decided I might as well create some tunes that nobody in the world was familiar with, that weren’t even similar to anything else. I set my mind to that and played around with it. I worked on it and it turned out that I could write these tunes with two and three part harmonies.” The development of the tunes, many of which were originally titled “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player, No. 2,” “No. 16.” etc., was slow and studied. Eventually they emerged as full blown, distinct compositions. Each began with certain themes and “movements” and once the form was set, they remained as a composed, fixed entity. Very little improvisation, if any, occurs even today when he performs the solo mandolin pieces.

During this period of Frank’s life he found it very difficult to make enough money with music to support himself. He’d relocated to upstate New York and often worked day jobs to insure a steady income. When he did perform it was often with hastily assembled pickup groups. The solo mandolin pieces, as well as most of his other original material, were not performed. It was rare when he was able to work with musicians of his talent and technical ability. Not only could most of these musicians not play Frank’s original compositions, they sometimes had trouble playing standard bluegrass. “It seems like I always had to teach them how to play.” He spent so much time and effort pulling his bands along that he had few chances to progress with any type of new ensemble sound. “There were so many times when I came into a town to do a show and couldn’t find enough good musicians. I’d have to play with whoever I’d get. We’d work real hard to make it good, but sometimes they just couldn’t do it. I’d get so embarrassed and feel so bad for all the people who came to see me and hear good music that I’d drink to make the night go faster. Of course that just made it worse in the long run. It made me look real bad for a long time.”

Mostly, according to Frank, it was a matter of talent and economics. “There weren’t that many good musicians around, and, if they were any good, I couldn’t afford to pay them.” Add to this the general lack of business sense Frank had and the built in difficulty of selling bluegrass music and you can understand the difficulties. Unfortunately for Frank and his fans a pattern emerged early in his solo career that dashed expectations and took many difficult years to break.

Still, the composing continued. As his efforts produced even more personally pleasing results, Frank found a new dedication in himself to his original music. The solo tunes blossomed and similar, slightly less complex band compositions began to take shape. Gradually he included these decidedly non-traditional tunes in his performing repertoire. If the bands weren’t capable of playing them, he’d perform them solo. This gave him added incentive to develop the solo pieces to greater harmonic complexity in order to give a fuller sound which could replace the other instruments.

He also began working with the autoharp about this same time. Again he approached the new instrument with ideas toward “being different.” He recut the chord bars to reflect the different chords he was hearing and proceeded to compose new autoharp and melodies to showcase his modifications.

The first recordings of the new mandolin and autoharp pieces are included on Frank’s first solo album “Frank Wakefield” (Rounder 0007) from 1972. Most of the selections were written by Frank and together they represent an historic first look at the many facets of his developing solo work. As a composer of strong biuegrass vocals Frank is well represented by three songs, “Leave Well Enough Alone,” (written in the early 1950s), “Tarry Not,” and “Counting on David.” His “Waltz in Biuegrass” is possibly the most beautiful bluegrass instrumental ever written and his “Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player, No. 2” and “No. 16” finally blew the lid off his growing fascination with mixing classical sounds, bluegrass, and the mandolin. It’s a very interesting album and the mandolin playing is superb throughout. It is also very possibly his best, most fully realized album project to date.

As his reputation grew as a composer and player of somewhat avant-garde bluegrass music, his problems with maintaining a working band continued. The day to day details of booking shows and hiring musicians was, and still isn’t, Frank’s forte, and he often found himself at loose ends and in financial straits. Still, once on stage, he worked all the harder at reaching his audiences. He began building a reputation as a powerful or maniacal performer, depending upon whom you talk to. There was a feeling and need in him to use his own energy to compensate for the shortcomings of his show. Since that time he has evolved a philosophy, and stage presence somewhat more reserved, of actively working to make friends with his audiences in order that they will accept his music more readily. ‘I’ve noticed that if I joke around a little bit it settles the other musicians and the audience. If you go out there dead serious and don’t do anything, you’re just another number to the audience. They don’t know whether to give you a good hand or not. You have to relax them, warm them up. You get on their side and they’ll get on your side.” Like everything else about him, it sets Frank apart.

It’s difficult for some to understand why he presents his shows in the way that he does. They claim that the comedy and intensity of the patter detract from the simple beauty of the music. Still, it must be said that audiences in general love Frank’s shows. His style projects well in large clubs and especially well at large outdoor shows. He gives audiences, even those most unfamiliar with his work or bluegrass, something to watch and think about. It’s really amazing to see him quiet a loud night club crowd with his beautiful, whispering solo tunes. He pushes out his energy and warmth and gets a great deal of it back in the form of satisfied listeners and enthusiastic fans.

These days Frank lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and works with his own trio—mandolin, banjo, and guitar. Together they are solidifying ideas which he began developing nearly twenty years ago. For the past two years they’ve toured the west coast and performed a mixture of bluegrass and Frank’s own original music. He’s put behind him the days of pickup bands and the pressures of being helpless in strange towns with strange players. Audiences are responding warmly from British Columbia to Texas.

Today Frank Wakefield is more determined than ever to see his music reach larger audiences. Just what type of music he’s playing may confuse and concern some listeners. When asked if he’s playing bluegrass, Frank responds, “Yes and no. Part of our show features bluegrass tunes done in the traditional style to please that part of the audience. Then I like to play my original music to please the other part. To tell the truth, most audiences like it all. You’d be surprised how well the Beethoven music goes over when it’s between some bluegrass songs. I hadn’t even realized that Beethoven had written mandolin music until one of my students told me.”

What you can expect from a Frank Wakefield show is mainly great mandolin playing. Much of it will be bluegrass music, some of this will be Frank’s original songs and tunes. You’ll also hear exciting new music played on mandolin, banjo, and guitar and wonderful, often unbelievable solo mandolin compositions in a classical vein. There are those who ask the question of Frank’s new music, “Is it bluegrass?” and predicate their like or dislike of it on the answer. It seems a shame to carve music up in such a way as it cuts one off from new ideas. After all, isn’t great music great music regardless of who puts what label on it? If Bill Monroe hadn’t pushed his ideas, even though they were different from the established norm, we’d not have bluegrass today.

Frank Wakefield is doing much the same with his music as Bill Monroe did over forty years ago. Yet Frank’s music is probably more in an established tradition than Bill’s was at the time. Certainly, Frank represents change, but change is good if the music is to grow and prosper. And, his input is so strong, powerful and creative, that it should not be ignored.

A SELECTED FRANK WAKEFIELDDISCOGRAPHY

Red Allen, Frank Wakefield and the Kentuckians Bluegrass” (Folkways FA 2408)

Frank Wakefield, “Frank Wakefield” (Rounder 0007)

Frank Wakefield and the Good Old Boys “Pistol Packin’ Mama” (Round RXLA597 G/RX-109)

Frank Wakefield and the Good Old Boys “Frank Wakefield and the Good Old Boys” (Flying Fish FF049)

Frank Wakefield “End of the Rainbow” (Bay 214}

Frank Wakefield “Blues Stay Away From Me” (Takoma TAK 7082)

David Grisman “Early Dawg” (Sugar Hill SH 3713) Frank Wakefield on only one cut

The Greenbriar Boys Better late Than Never” (Vanguard VSD 79223)