Home > Articles > The Archives > Fiddlin’ Paul Warren

Fiddlin’ Paul Warren

By Doc Hamilton and Dick Spottswood

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1978, Volume 12, Number 8

It is with a great deal of sorrow that we note the passing of Paul Warren in the early morning hours of January 12th at Baptist Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee. Paul had been a patient in the hospital a number of times in the past year during a lengthy illness. He was 59.

We wish to extend our deepest sympathy to his wife and family on their, as well as our, great loss.

The 1970s has seen a resurgence of interest in fiddling of all kinds, and especially in bluegrass. It’s a real resurgence too, because back in the early 1960s when the Osborne Brothers and the Country Gentlemen were first experimenting with integrating popular music into their formats, their bands and others who followed found it desirable to eliminate fiddling altogether from their music. This movement corresponded with another trend in Nashville to drop the fiddle and emphasize in its place varied types of pedal steel and electric guitar, not to mention the superfluous choruses and horns, all of which were being developed with the purpose of presenting a “countrypolitan” music as a compromise between the older honky-tonk sounds of the 1950s and the emerging hard rock of the sixties. Unlike the Gentlemen or the Osbornes whose country roots remained evident, the new Nashville sound was more middle-of-the-road pop music than country. For awhile Nashville was in danger of losing its musical identity and, more to the point, many good fiddlers were facing lean years.

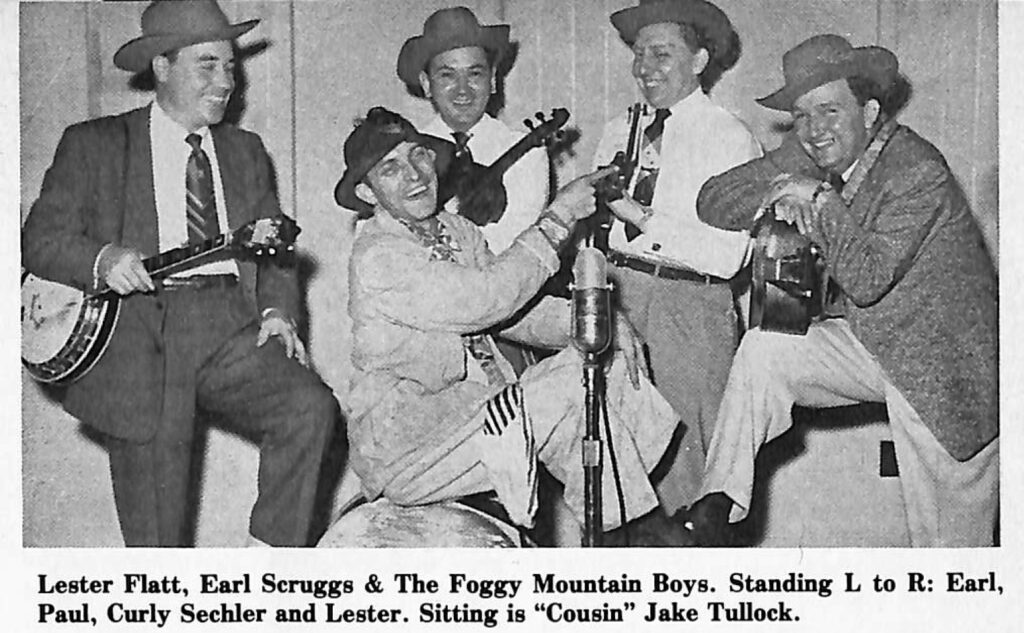

Paul Warren was not one of them. Since 1954 he had been a mainstay of the prospering organization led by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. With them he had worked backbreaking schedules from 1954 onwards which consisted of far-flung tours, a regular live morning show for Martha White Flour over WSM, several TV shows, the Opry and frequent recording. It was hard work, but still they were prosperous years. Lester and Earl were succeeding against all odds in bringing their music out of the confines of local radio and one-night schoolhouse shows into the public eye and the big-time. Paul Warren was around for most of it and was instrumental (pun intended) in making it happen.

Warren was a seasoned pro by 1954. In his own words: “I was born in a little place called Lyle, Tennessee, about 45 miles southwest of Nashville. My dad was a fiddle player and banjo-picker and my mother played banjo too, clawhammer style. I’ve got one brother who plays the banjo and a sister who plays the guitar. I was 13 when I started playing fiddle a little bit, usually just for parties or around home. I was going to school then, and farming when school was out.

“We didn’t have a radio back then until we got electricity. Before that we had an old coal oil lamp, and later an Alladin lamp which burned kerosene, but you had to pump air into it. Finally we got electricity and a radio, and we started listening to the Grand Ole Opry. That was when I heard Arthur Smith, who was more of an inspiration to me than anybody else back at that time. I really didn’t play actively until I graduated from high school. Then I joined up with Johnnie and Jack on WSIX in Nashville. Ernest Ferguson (later with the Bailes Brothers) was playing mandolin and Emory Martin, the one-armed banjo-player, was with them too. I made my first records with Johnnie and Jack a little later on, when we went to New York and recorded for Apollo. Eddie Hill (guitar) and Paul Buskirk (mandolin) were with us then. Paul came from West Virginia and I’d seen him when I was working on WHIS in Bluefield. He was up there then with his brothers: Buster played guitar and Willie played bass.

“I was with Johnnie and Jack a little over 13 years. I left them once in Knoxville when I was drafted in World War II. I was a prisoner of war for a little over two years. When I came back they were working on WPTF in Raleigh, and later we went to Shreveport. The Bailes Brothers and Johnnie and Jack were the ones who started the Louisiana Hayride (broadcast over KWKH in Shreveport) and I used to play the theme when the show opened up on Saturday night, ’Come Along, Little Children, Come Along.’

“While I was in the Army, Johnnie and Jack had hired another fiddle player named Aaron Sumner from Hazard, Kentucky. When I came back, we played together (with twin fiddles) for about four months. They got to deciding that was too smooth, and they wanted to drop one fiddle player. I was in pretty good shape financially, so I let Aaron keep the job. I went with Homer Briarhopper who was on the same station (WPTF, Raleigh). We both had early programs, so I worked with Homer about four months, and then I went back with Johnnie and Jack, and stayed with them until 1954.”

Warren’s long tenure with Johnnie Wright, Jack Anglin and Johnnie’s wife Kitty Wells, was during the years of their rise to popularity. The Apollo records sold poorly, partially because that label was primarily involved with recording black gospel music and early rhythm and blues. It even ventured briefly into Greek music (hence the name of the company) but they had no more success with it than in the country field. Johnnie and Jack’s fortunes improved when they joined RCA Victor in 1949 and the Grand Ole Opry in 1952. These were the years which produced their most memorable songs, including “Ashes of Love,” “What About You,” “Poison Love,” “Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide,” “I Can’t Tell My Heart That” and a number of fine hymns, all of which added to their popularity and became classic country songs. Along with Shot Jackson, the steel and later Dobro player inherited from the Bailes Brothers, Paul Warren was an integral part of the band sound which enhanced these songs.

Nevertheless, the records don’t do much to show Warren off as a fiddler. To sell their songs, Johnnie and Jack relied on the strength and unique blend of their voices, the songs themselves (many of which were written by them and Jack’s brother Jim Anglin) and the distinctive growl of Jackson’s steel. On records, Warren’s work was limited to reticent harmonies and occasional breaks between verses which were usually simple restatements of the melody. Surely there must be some broadcast transcriptions of those early years which feature the good breakdown fiddling Paul Warren later became famous for.

“I stayed with Johnnie and Jack until I joined Lester and Earl on February 16, 1954,” Warren says. “Benny Martin was there just before me. I’d heard Lester and Earl a lot, and you couldn’t help but take notice about what they were doing. When they hired me, I figured they wanted the tunes played like they were on records, but I told them I couldn’t play like Benny or anybody else. I tried to get close to the tune and carry it. They didn’t pressure me at all. They said, ‘just play it the way you feel’.”

According to Lester Flatt, “I tried to talk him out of coming with us. But every time I’d see him he’d ask again, so I finally went to Johnnie and Jack about it. When he first joined he would try too hard sometimes because he liked Benny’s playing. But pretty soon he fell right in. It was amazing at first; I didn’t think he could do it. But he turned into a first-class fiddler. You couldn’t beat him with a stick; he’s just a real trouper.”

Warren had to be a real trouper. When he joined the Foggy Mountain Boys, they were on a grueling schedule, putting in over 2,500 miles on the road each week. The Martha White morning shows on WSM were aired up to seven times a week, and all of them were done live until the station allowed pre-show taping. There were radio shows in Knoxville, the WRVA Barn Dance in Richmond, Virginia, later a weekly television show on WSM and personal appearances which carried them regularly throughout Tennessee, Georgia, the Carolinas, the Virginias, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Almost immediately Warren’s fiddle became more prominent on records than it had been in the days with Johnnie and Jack. The Foggy Mountain Boys instrumentals were justly celebrated in those days, and were an influence on many young musicians who slowed them down to try and learn how to play them. Following their association with Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs wanted to present music more distinctively their own. The hot mandolin sound was left for Monroe, and the instrumental solos on the Foggy Mountain Boys records were largely left up to the fiddle and banjo. Paul Warren proved more than capable of carrying the increased load, though it later decreased somewhat with the addition of Buck Graves’ Dobro.

Not long after joining, Warren and Scruggs began working out some special music which heightened the former’s skills and emphasized the contributions he was making. “Lester had the idea for us to play some fiddle and banjo tunes, because that was mainly what they used back in the old days. I remember sitting around in our dressing rooms trying it out, and oh boy, it sounded kinda authentic, and Lester said we ought to do something like it on stage.” It worked out well. The novelty of seeing two good musicians playing old-time breakdowns with all the force of a full band was irresistible to audiences, and the old-time fiddle and banjo numbers were featured regularly on radio, tv and appearances for years. It must have been considered risky business for records though, because little of this fine music ever appeared on Columbia. Some tapes made over the air from this era have appeared on an unauthorized release, however, and a couple of tunes by Warren and Scruggs are exhilarating workouts and show clearly just what the excitement was all about. Another specialty was Warren’s “Black-Eyed Susie” which he sang and played with the full band at breakneck speed.

Paul Warren remained with the Foggy Mountain Boys until Lester Flatt parted company with Earl Scruggs in 1968. Flatt’s new band, the Nashville Grass, continued to feature Warren in a more traditional setting than Flatt and Scruggs had presented in their last years together. Warren has played continuously with Flatt for just under 23 years, leaving only on January 23, 1977 to battle a lingering illness.

“I only took a couple of days off for an operation in 1972. Other than that I never missed a show the entire time.” Lester Flatt confirms this, and claims that “Paul Warren is one of the solidest, most dependable musicians that ever played.” Warren: “Of course, Curly (Sechler) was in the band before I came in, but he was gone for about 12 years. I never left from the time I joined. When you’re in show business and you got a job to do it’s like the mail, it must go on.”

Quite right. And a significant statement from a man who is modest about his art, valuing his consistency at least as much as his skill. The world of bluegrass has seen many others, even brilliant performers, who have taken their work less seriously, and still others whose health has not allowed them to work at the same level of dependable intensity as a musician like Paul Warren. As he traveled, performed and recorded he became the most widely heard fiddler in bluegrass through the phenomenal exposure Flatt and Scruggs enjoyed. Because of it, his fiddling became definitional for many so far as bluegrass was concerned, even though he did not radically alter his music when he left Johnnie and Jack. He has never made a solo album, and one is long overdue. If it should materialize it will help us all to release the work of an important and surprisingly neglected figure.

To conclude, some of Paul’s observations on music give a further insight to the man: “Plain old country fiddle is what I like, and it takes a lot of practice and staying with it. You got to live fiddle, that’s the way I look at it; keep your ears open, learn all you can. Some can do it and some can’t. It doesn’t come to you; you have to go get it. The fiddle’s harder, because there’s no frets and bow work is a hard thing. You have to have good coordination between your fingering and your bow. You can’t give it up if you haven’t learned to play in a year. I’ve played all my life and I’m still learning things. You never learn it all; nobody ever learns it all.

“I like Howdy Forrester, Kenny Baker—anybody that plays well, and there’s quite a few of them. I especially like Howdy because of the precise way he plays hard tunes. Clark Kessinger was a great fiddle man. I used to know him in Charleston, West Virginia when I was there with Johnnie and Jack on WCHS. When I worked in Shreveport, we used to go to Texas quite a bit. I worked a fiddler’s contest over in Gilmer, where Buddy Brady won first prize and I got second. I liked all those fiddlers. I’m all ears, you know, and any time I can hear something different I want to.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Who is going to fill his shoes?