Home > Articles > The Archives > Fiddler in the Shadows — The Story of Tommy Magness

Fiddler in the Shadows — The Story of Tommy Magness

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1997, Volume 31, Number 11

“There are three types of history for our music,” said the old man. “There’s mullet history—that’s the kind you tell to people from Minnesota who don’t know what a banjo is. Then there’s book history—that’s where you divide up the music into a different chapter for each legend. And then there’s the shoptalk history, stuff the pickers tell each other about the secret history of bluegrass. That’s where you hear about people like Joe Lee, Blue Millhorn, Emmett Miller, Arthur Q. Smith, Kennedy Jones, Mac McGarr, Amos Johnson, and all the rest of those invisible heroes. And don’t forget the one who may have been the best of them all—the fiddler Tommy Magness.”

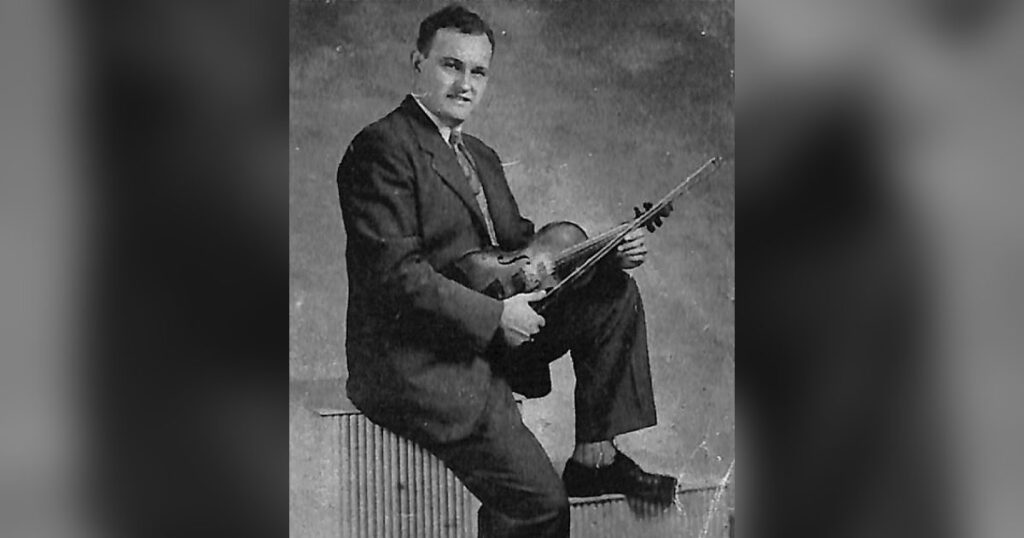

Bill Monroe never forgot about Tommy Magness. “Tommy Magness worked for me in 1940, and was on my first records,” he recalled. “He had that fine old-time touch, rich and pure, but he was able to put a touch of blues to it. He was the first man I heard play ‘Orange Blossom Special,’ and he could put a lot more in it than they do today. He taught me the song ‘The Hills Of Roane County,’ and I taught him to play ‘Katy Hill’ in the bluegrass way.”

Through the 1940s Tommy Magness became one of the most visible fiddlers on the country and bluegrass scene; he played with three of the biggest stars of the time—Roy Hall, Bill Monroe, and Roy Acuff—and helped start the careers of Reno and Smiley. He was instrumental in popularizing two of the best-known fiddle tunes, “Orange Blossom Special” and “Black Mountain Rag.” He was heard on network radio, seen in Hollywood films, spotlighted on major record labels, and toured from Maine to California. His fiddling was a complex bridge between the older Appalachian folk fiddling, the new country music styles of the 1940s, and the even newer emerging sounds of bluegrass. Yet Tommy Magness remained an enigma, never settling in any one band for more than a couple of years, restlessly moving around the south, never getting the formal recognition he deserved. Somewhere in the 1950s he just dropped out of sight, even though he wasn’t that old, and only a few close friends knew what had happened. For awhile people asked, “Whatever happened to Tommy Magness?” And not many people knew, so after a time people stopped even asking. Except for a few who remembered the sweep of his little bow, and the soaring drive of his old records. But something had happened to Tommy Magness, and it’s a story worth telling.

The impression one gets from talking to admirers of Tommy Magness was that he was an old, colorful musician who had been born in the 19th century, like John Carson or Eck Robertson or Fiddlin’ Cowan Powers. Yet he was, as fiddlers go, a relatively young one, and one who died relatively young. He was in fact born on October 21, 1916, near the north Georgia community of Mineral Bluff, in the mountains not far from the Tennessee line. The area had produced two other well-known fiddlers. One, by far the most famous, was Fiddlin’ John Carson, who had come from Blue Ridge, just a few miles to the east. Carson recorded and broadcasted widely in the 1920s, making dozens of records for the OKeh and Bluebird labels, and being widely hailed as the first country entertainer to make records (in 1923). The other was Allen Sisson, a much less known but important fiddler who was raised in Gilmer County, Ga., but who settled in Copperhill (Polk County), Tenn. Born in 1873, Sisson won nationwide fame in the 1920s when he broadcasted over NBC radio and recorded ten of his finest for the Edison Company. Though he played in a fussy, ‘almost prissy style, his repertoire included several pieces that would later become Tommy Magness’s favorites, including “Katy Hill” and “Farewell Ducktown.” (Ducktown is a small community in the Copperhill area, which in general is one of the South’s most notorious examples of strip mine devastation.) Tommy’s family remembers that he knew and performed some with Allen Sisson, but to modern ears there’s not much stylistic connection between Tommy’s work and the recorded work of either Sisson or Carson.

Most of the Magness style seems to have come from family and local musicians in the north Georgia hills. Tommy’s father was a farmer and gardener named Reuben Magness, whose main instrument was the banjo. This was Tommy’s first instrument as well, and family legends tell of him standing at age three or four, in a chair and managing to hold and finger the instrument as he tried to learn tunes. They also tell of his fascination with playing corn cobs—one acting as a fiddle, the other as a bow. His older sister Leah recalls: “When he was a crawling baby, he played with those two cobs. I would joke him, and go hide those cobs, and he would just sit there and cry. Those two cobs suited him.” But finally Reuben got the boy a real fiddle—of sorts.

Leah: “The way it came about, we didn’t have no toys, and when daddy was working at Copperhill, he built Tommy a fiddle, and I learned to play it. I had learned the fiddle from watching mother pick the mandolin. Daddy just played banjo. Then I taught Tommy when he got big enough.”

By the time he was nine, Tommy was good enough to start playing in public with his fiddle. One of his first jobs was playing for a local celebration at Hampton’s Hardware Store, entertaining customers. About this time, he and his sister had a fight over the homemade fiddle, and broke it. (“The dog got that one,” laughed Lena.) His parents, sensing talent afoot, replaced it, and soon Tommy was playing with local bands. He played around Mineral Bluff with a guitar picker named Bob Baugh, and a man named Booney Anderson. “They made all kinds of music growing up, they’d play in those tea rooms on the ridge. They’d have dances there, they’d call ’em that, tea rooms, but I guess they had drinks, cause he’d always come back drunk,” says Lena. We don’t have a clear idea of what kind of music the trio was playing, but on at least one occasion this became an issue. “One time a fiddle got busted over Booney Anderson’s head. He was whistling ‘Farewell Ducktown’—that’s Allen Sisson’s tune, about the same as ‘Flop-Eared Mule.’ Bob was trying to learn it and was whistling it all the time. Booney told him if he didn’t stop whistling that, he would cut him up. Well, Bob was Tom’s favorite buddy, and finally Booney had enough. They were coming back from somewhere in a car. And Booney pushed Bob out of the car. So Tommy got out and made Bob get back in and busted his fiddle over Booney’s head. That was before Tommy was 16.”

Another local band that Tommy knew was the one led by the Chauncey Brothers from nearby Ellijay in adjoining Gilmer County. (Fiddler Chelsey Chauncey is discussed in Gene Wiggins’ biography of John Carson, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy.) It seems likely that this band might actually be the source for much of the later Magness style. One of the tunes that they all seemed to be playing during these years—the late 1920s—was some kind of version of what would become one of Tommy’s signature pieces, “Black Mountain Rag.” Chelsey Chauncey remembered quite clearly that he won his first awards at a fiddling contest playing this tune, and Tommy’s sister recalls that she and Tommy twin fiddled the tune during this time. “We didn’t call it ‘Black Mountain Rag,’ though—that came much later. We made up lots of tunes, and lots of times Tommy liked to retune for numbers.” Like a lot of fiddlers, he retuned for “Bonaparte’s Retreat.” And he got to believe there was magic in it. “One time him and a bunch of musicians from Copperhill went out and got to starving. They got down in Atlanta, off with some show down off the mountain, and decided they would start walking back home—all the way from Atlanta—over 100 miles. Tommy, when he got down and out, he’d always tune up his fiddle and play ‘Bonaparte’s Retreat’ and try to get some help. So they all crawled up on the bank [by the road] and he got his fiddle out and started playing. Lester, one of the boys, was quarrelsome and said, ‘What in the world are you trying to play, with us starving to death?’ Tommy just played right on, and sure enough, the daddy and mother of one of the boys happened to be driving along and picked ‘em up and got ‘em. Tommy was only about 12 at the time.”

Not long after this Tommy began to get a taste of the newly developing professional country music scene. He attended a local show by Pop Eckler out of Atlanta, WSB’s Crossroads Follies. “They coaxed him up on stage,” recalls Faye Harris, Tommy’s daughter. “It took some coaxing. But he played ‘The Mocking Bird’ and then something else for an encore. He went back with Eckler that night, and he played a while with them.” Later, Tommy made other attempts to go out on his own, most reflecting an amazing confidence in the face of the deepening Depression. His widow, Leah, remembers: “When he left home he only took his fiddle and some clothes. He got so hungry he couldn’t stand it, and took his fiddle into a cafe. They asked him to play a tune. He did, and said he got steaks or biscuits or anything he wanted.” In between these trips, he did work at Beacon Mills, a blanket manufacturer.

During Tommy’s later childhood, the family moved back and forth to North Carolina, and Tommy’s mother died there when he was eight. Not surprisingly, around 1932, when Tommy was 16, he quit school and moved to Canton, N.C., near Asheville. There he began working with a family headed by Carl McElreath, who maintained a string band and a group of dancers. In between playing on the radio and at festivals, the family built rock houses around Canton. One of the McElreath children was Carl’s sister Ruth. She was a fine guitarist and a superb musician in her own right; when she began competing against the rest of the family, she often won the trophy at contests. Eventually, the boys got to where they wouldn’t let her enter; at one particular contest in Asheville, the family took off leaving her at home. Furious, she hired a taxi, went to the contest, and won the prizes anyway. Stunts like this impressed young Tommy, and when he was 18 he married Ruth. Two children soon resulted, although one died in infancy.

The next few years are a little confused. We get glimpses of Tommy going to work in the nearby Deacon Mill, and playing over the radio in Asheville—WWNC—free of charge to advertise himself. He must have known some of the important Asheville area fiddlers, such as Marcus Martin or Pender Rector or John D. Weaver, but there is no documentation of this. As he sought work on the radio, in the mid to late 1930s, the so-called golden age of old-time fiddling was in decline; there were fewer and fewer programs featuring exclusively fiddle music, even in the mountains, and the fiddle was being relegated to a backup role for the new breed of entertainers—vocalist. The typical radio show now featured a smooth-voiced singer, a comedian, duet singers, and maybe one or two short token “fiddle breakdowns.” In one sense, Tommy was hitting the media just about a decade too late.

One of the new radio singers was a handsome young man from nearby Waynesville, N.C., named Roy Hall. Coming from a family of mill workers, Roy and his brother Jay Hugh began recording their duet singing and recording for major record companies in 1937 and broadcasting over WSPA in Spartanburg, S.C. After his brother left the band, Roy organized a string band called the Blue Ridge Entertainers. It was built around Hall and resonator guitar player Bill Brown, tenor banjo player Bud Buchanan, and Wayne Watson on bass. By the Spring of 1938 Hall had asked Tommy Magness to join him on fiddle, and Tommy accepted. Soon he was being heard not only over WSPA but over WWNC in Asheville and WBIG in Greensboro. By the fall of 1938, the band had moved to WAIR in Winston-Salem, where they had a popular show sponsored by Dr. Pepper. Roy Hall’s star was ascending, and within months he would become the most popular singer in the Carolinas. And listeners were paying more and more attention to the moonfaced fiddler whose rich tone and mellow double stops were adding too much to his backup band.

It was with this band—or a version of it—that Magness made his first commercial recordings—for the old American Record Company, at a makeshift studio in Columbia, S.C., on November 7, 1938. Sixteen sides were cut, but most were never issued; the ones that did get released included one of Hall’s best known, “Come Back Little Pal” and “Where The Roses Never Fade.” Among the casualties, however, was one that would loom large in Tommy Magness’s career: “Orange Blossom Special.” About halfway through the session, Tommy cut a version of the song on master number SC-93. Tommy may not have known it at the time, but this was the very first recording of Ervin Rouse’s famed train piece. Though the detailed circumstances of how the song came about are still unclear, the piece was obviously becoming very popular with radio fiddlers in 1938. Just where Tommy picked it up is not known, either. But Ervin Rouse had in fact copyrighted the song by now, even though he and his brother would not make their own first recording of it until June 1939, almost nine months later. The A&R chief for the American Record Company, Art Satherly, sensed a good tune when he heard Tommy’s version, and wanted to release it; somehow, though, the Rouse Brothers found out about the Magness recording and managed to block it. “Hold release, Rouse Brothers refuse to sign contract,” read one note in Satherly’s files. On the recording ledger itself was another note: “Don’t release—Pub. promises trouble.” Obviously the Rouses wanted to have the first release of their song—and did so—and so Tommy Magness’ version, which Bill Monroe so admired, was left to languish in the ARC-Columbia files. (According to later notes in the Columbia files, the master was destroyed during World War II and melted down for scrap metal.)

The Hall band continued to do well on the radio and in 1939 moved up to WDJB in Roanoke, a city Tommy would use as his headquarters off and on for the rest of his career. Here they started a live Saturday night show called “The Blue Ridge Jamboree,” which attracted a wide range of guests from the Carter Family to Roy Rogers and Gabby Hayes. The band would do two more important record sessions in 1940 and 1941—this time for RCA’s Bluebird label. Tommy would be featured on both of them, and play on the Blue Ridge Entertainers’ biggest hit, “Don’t Let Your Sweet Love Die,” recorded in Atlanta in October 1940. His own two specialties — numbers he is still remembered for in the Blue Ridge area today — were “Natural Bridge Blues” and “Polecat Blues,” both done in Atlanta in October 1941. Both tunes are still in the modern repertoires of such Virginia fiddlers as Greg Hooven and Rafe Brady.

In 1940, though. Tommy left Roy Hail for a sabbatical with another major string band which was in the process of defining itself: Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. Monroe had gotten a slot on the Grand Ole Opry in late 1939, and was being featured on the new NBC network part of the show. Monroe was attracted to the drive and loose, bluesy style of Magness. He recalled: “Now Tommy Magness had been playing with Roy Hall and they were trying to play off of bluegrass. He’d heard the way we played when Art Wooten was with me, so it was right down his alley to get somebody behind him with that, because with that kind of little bow he worked, he could move you right along.” Monroe’s reference to Tommy’s “littlebow” is revealing; it suggests that, even though he respected the so-called “long bow” artists like Arthur Smith and Clayton McMichen, Monroe also saw a place in his music for the older mountain “jiggy bow” style—of which Mangess was one of the very best. It turned out to be Magness who backed for the Victor company in 1940 in Atlanta.

Tommy was also featured on most of the other seven songs from the session, playing some evocative blues on Clyde Moody’s vocal of “Six White Horses,” some greasy shuffling on. “Dog House Blues,” and some nice J.E. Mainer licks on “I Wonder If You Feel The Way I Do.” His masterpiece of the session, though, was the soaring “Katy Hill,” played at the kind of breathless tempo that was winning Monroe his reputation. “‘Kaly Hill’ had more in it when we recorded [it] than it ever had before,” Monroe recalled. “Those old-time fiddlers didn’t have anybody to shove them along.” Magness did: he had three of the best rhythm in the music back then: Monroe, guitarist Clyde Moody, and veteran bass player Bill Wesbrooks. Fans responded by buying the record in droves.

Curiously, most of these Bluebird records that won Tommy his reputation were done in one marathon session in Atlanta during the first week in October 1940. On the 7th he did his Monroe session, and two days later he helped out his old boss Roy Hall for the session that produced “Don’t Let Your Sweet Love Die.” And in between he helped out Arthur Smith by playing twin fiddles with him on a couple of his recordings. But by the next big Bluebird field session a year later—October 1941—Tommy had left Monroe and was back full-time with Roy Hall. It was at that session that Tommy recorded “Polecat Blues,” and watched Art Wooten record “Orange Blossom Special” with Monroe. Hall’s popularity by now had grown so much that he was running two separate bands to take care of demand, and was able to pay Tommy better than the $25 dollars a week union scale he was getting with Monroe. By now his first marriage had fallen apart, and in 1942 he remarried a Virginia girl named Tootsie Poindexter.

Throughout the early years of World War II Tommy Magness continued to work with Roy Hall for Dr. Pepper at Roanoke. Then tragedy struck: Roy Hall was killed in an automobile accident on May 16,1943. Several months before, however, Tommy had decided to leave the band anyway after two years broadcasting, and move to WHAS in Louisville, where he appeared on the Early Morning Frolic show. After about a year of this, though, he received an offer to return to Nashville—not to work for Bill Monroe, but for an even bigger name: Roy Acuff.

Acuff, of course, was himself a fiddler and had in fact first won his job on the Opry as a fiddler back in 1938. But now his forte was his distinctive singing style, and as he became more and more popular in the early 1940s, he found himself doing a number of jobs: he was master of ceremonies, lead singer, band leader, songwriter, actor, businessman, and founder of Acuff-Rose publishing, the company that laid the foundation for the modern Nashville music business. By 1944 he had decided that while the fiddle was still a key part of the Smoky Mountain sound, he no longer really had time to do it himself; for the first time in his career, he decided to hire a fiddler. After hearing Tommy’s mellow mountain style, and the way he had backed up Roy Hall’s vocals, he made the offer. Tommy accepted at once.

When Tommy and his family drove to Nashville in 1944, Roy was the most popular country singer in America. His Prince Albert portion of the Grand Ole Opry was heard every Saturday night at 9:30 Central War Time over NBC from coast to coast; his Republic feature films were seen in theaters across the country; his tent shows and stadium tours played to thousands more; his Columbia and OKeh singles were constantly in the top ten of the new Billboard charts. His band was an amiable and versatile bunch that included Beecher “Oswald” Kirby, arguably the best resonator guitarist in the business; Rachael Veach, the pioneer woman banjo player whom Acuff billed as Oswald’s “little sister” to prevent fan criticism; Jimmie Riddle, the remarkable harmonica player who had learned his trade in the bars of Memphis; Jess Easterday, a no-nonsense old-time guitar and mandolin player who became one of Tommy’s close friends; and Joe Zinkan, the bass player who later became a Nashville studio regular. (Lonnie “Pap” Wilson was by now serving his hitch in the Navy.)

Tommy fit in well here, and for the next two years became probably the most widely heard old-time fiddler in the nation. Shortly after he joined Roy the band traveled to Hollywood to film Acuff’s fifth Republic musical, Sing, Neighbor, Sing, where Tommy appeared in two other films, Night Train To Memphis (1945) and Smoky Mountain Melody (1948). He also became a regular on Roy’s records, appearing on such classics as “Wait For The Light To Shine” (12/44), “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain” (8/45), “No One Will Ever Know” (8/45), “We Live In Two Different Worlds” (8/45), and “Pins And Needles (In My Heart)” (8/45).

Once again, though, just as Tommy was on the verge of establishing his career, fate intervened. Acuff, in a dispute with the Opry management, decided to leave the show and strike out on his own. Acuff invested thousands of dollars in his own traveling tent show, and made plans to spend far more time on the road. It would yield more income for him and his band, but without the requirement to be in every Saturday for the Opry, it would mean far more traveling. With a growing family, such traveling was not appealing to Tommy, and when Acuff really quit the show—on April 6, 1946—Tommy and steel guitar player Wayne Flemming decided to return to Roanoke and WDBJ.

By June 1946 Tommy had formed his own band, Tommy Magness and the Orange Blossom Boys, an interesting band that was part western swing, part honky-tonk, and a touch of bluegrass. It included Clayton and Saford Hall (not related to Roy), Jay Hugh Hall (Roy’s older brother), singer Warren Poindexter, and steel player Slim Idaho. The latter was one of the first to use an electric pedal steel, and Tommy’s announcer always referred to him as “big Slim Idaho with his strange three-necked steel guitar”—suggesting that he either made his own instrument (as did many early pedal players) or was using one of the very first Fender pedal steels. Idaho was a remarkable instrumentalist and a key innovator on the pedal steel; he later played on WRVA and became known for his stunning work on Cowboy Copas’ “Jamboree” single of 1949. With Tommy, he helped play the band’s theme song— “Orange Blossom Special,” of course—and did take-off solos on items like “Texas Playboy Rag.” Tommy, for his part, did traditional breakdowns like “Cotton Eyed Joe,” but also did Joe Holley-styled take-off solos on western swing pieces. In September 1947, the band recorded its only commercial record, for the Roanoke-based Blue Ridge label: “Sitting On Top Of The World” backed with a new train instrumental, “Powhatan Arrow.”

The Orange Blossom Boys built a solid reputation in Roanoke in 1946, and Tommy’s use of the “Special” as his theme song helped spread the popularity of the tune in the Southeast. But then in April 1947, Acuff returned to his niche at the Grand Ole Opry, and made Tommy an offer to return to the more settled life style at the Opry. Tommy broke up his Roanoke band and moved back to Nashville. The problem was, Acuff’s career was about to go into high gear again. In November 1947 there were two huge recording sessions for Columbia, stockpiling sides for the forthcoming recording ban. In July 1948, there was another trip to Hollywood, this time to film Smoky Mountain Melody, and in November yet another one to film Home In San Antoine. In between was something Tommy had not expected at all: Roy Acuff’s run for governor of Tennessee. He was part of Acuff’s official “campaign band,” which included Oswald, Jimmie Riddle, Sonny Day, Jess Easterday, Joe Zinkan, and Lonnie “Pap” Wilson. Rachael Veach even came out of retirement to play banjo. This group barnstormed the state with Roy, doing 100 shows in 64 days, and managing to gel back Saturdays for the Opry.

Throughout much of the campaign, Acuff had to defend himself against charges that he was only a “hillbilly fiddler” and the fact that opponents sometimes referred to him only as “the fiddler.” This made him, if anything, defensive about fiddling, and how complex an art it really was; he came to increasingly respect Magness’ fiddling skills, and soon was letting Magness use his own fiddle on the stage. In March 1948, even before the campaign had begun, Acuff had taken Tommy aside and asked him if he would privately record his old-time fiddle tunes on a home disc recorder that Roy had bought. Oswald was brought in to play backup guitar, and Tommy began to go through his repertoire. He started with some of the old Fannin County-Ducktown tunes he had known as a child—things like “Farewell Ducktown” and “Forked Deer” and “Little Old Log Cabin” and “Liberty” (the old version). He did some of the western swing tunes from his recent stay at Roanoke and being a “radio fiddler,” such as “San Antonio Rose” and “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” and “Under The Double Eagle” and the odd, haunting “Bob Wills Stomp.” There was a healthy helping of Arthur Smith tunes, such as “Blackberry Blossom,” “Florida Blues,” “Fiddler’s Dream,” “Bill Cheatam,” and “K.C. Stomp.” There were the familiar Magness favorites like “Black Mountain Rag” and “Orange Blossom Special” and the blazing “Katy Hill” he had recorded with Monroe—but not the two great Roy Hall pieces “Natural Bridge Blues” and “Polecat Blues.” Most of the southern fiddle standards were there, but sprinkled among them were a bevy of odd and unusual tunes, such as “Duck’s Eyeball,” “Rock Oaks Studman,” “Grandpa’s Rag,” “Magness’ Reel,” “Lady Hamilton,” “Booth,” and “Up Jumped Trouble” (which had been popularized by Mac McGarr on the Opry in the early 1940s. All told, Tommy laid down over 130 tunes for Acuff’s recorder, but for some reason Acuff limited the length, and so few of them are no more than 60 seconds in duration. (This is probably one of the reasons they have never been issued to the public, for their sound quality is generally excellent.) The only real problem is that Tommy and Os got no real chance to rehearse, and occasionally Tommy’s odder tunes throw Os off or give him chord changes he can’t believe. “Sometimes Tommy had to shout out where to go,” Oswald recalls today. “He would get into some of those old tunes that neither Roy or I either one had ever heard before.”

(The discs had an interesting effect on Acuff. Years later, in the 1970s and 1980s, Roy began to get interested in his own fiddling again. He did so by bringing the old Magness discs up to his dressing room at the Opry, and playing them for his own enjoyment, or to impress visitors. Friends, say that it was these discs that got Roy to thinking more about fiddling, and to start sharpening up his own skills.)

Another effect of this set of home discs came the next, year, in 1949, when Acuff devoted an entire album to Tommy’s fiddle music. In January 1949, after a session where Acuff recorded his Magness-flavored version of “Tennessee Waltz,” the band recorded eight fiddle tunes featuring Tommy: “Grey Eagle,” “Dance Around Molly,” “Black Mountain Rag,” “Pretty Little Widow,” “Smoky Mountain Rag,” “Lonesome Indian,” and “Bully Of The Town.” The records were released as a 78 r.p.m. album (No. H-8, “Old Time Barn .Dance”) in May. The album was a part of a national fad for square dancing and square dance records in the late 1940s, but it did get some of Tommy’s very finest fiddling preserved. In the process of doing the paperwork, Acuff-Rose filed a copyright on “Black Mountain Rag” in Tommy’s name— a copyright that still yields the family royalties today.

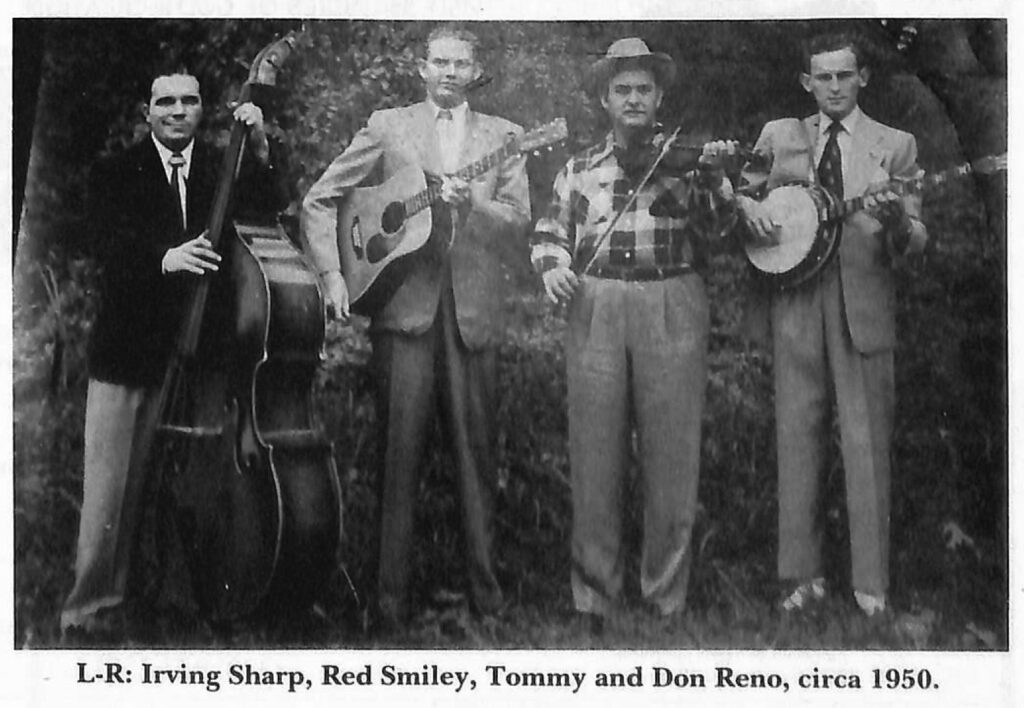

Not long after the square dance album was recorded, Tommy left Acuff again. One widely circulated story was that Tommy left because his wife had bought a new Chevy and he couldn’t wait to get home to drive it. A more likely one was that Tommy had again burned out on touring, which was now being done a lot on an airplane Acuff had bought (called, of course, “The Great Speckled Bird”). By 1950 he was back at WDJB in Roanoke, and had organized a new band which he called the Tennessee Buddies. The original personnel included Tommy on fiddle, Hal Grant on mandolin, Dexter Mills on bass, Red Smiley on guitar, Verlon Reno on guitar, and Don Reno on banjo. Later on, Cousin Irving Sharpe replaced Mills on bass, and also occasionally played piano. A baggy-pants comedian known as “Chicken” provided the comedy.

Tommy had known the Reno family for some time. Lena Magness, Tommy’s sister, was living in Canton as the Renos were growing up, and recalls that Tommy and Don Reno even played some together in Spartanburg. “He couldn’t play too good with Tommy then,” she recalled. The boys, though, hung around Lena’s house a lot. “I tuned Don’s first banjo. His brother had bought him a banjo for Christmas, and he couldn’t even tune it up. And I helped him tune it up, I learned him how all winter. He tormented the life out of it.” By 1950 Don was no longer tormenting the banjo, and had in fact already served an important stint with Bill Monroe. When Tommy heard he was available, he sent for him to join his band, and soon Don was reunited with his cousin Verlon.

Before the band could hardly get on its feet, tragedy struck again. On June 20, 1950, Verlon Reno drowned while swimining in the Cowpasture River. Tommy especially was devastated by the loss. His daughter remembers: “When Verlon drowned, it just about killed daddy. For he never did have a son and he thought the world of that boy.” One of the early Tennessee Buddies songbooks has the words to a tribute Don wrote about his cousin, “A Rose On Cod’s Shore,” which Don began to sing as a duet with the group’s guitar player, Red Smiley. (The pair would later record it for their first King session under their own name.)

Though the Tennessee Buddies could sport three men who would later become bluegrass legends, by the middle of 1950 they were still not quite a bluegrass band. Their songbook included songs like Hank Snow’s “I’m Movin’ On,” Don Reno’s “The Talk Of The Town,” Bill Monroe’s “I’m Blue—I’m Lonesome,” Reno’s “Little Country Preacher,” Hank Williams’ “Everything’s Okay,” Stuart Hamblen’s “Remember Me,” Hank Garland’s “Sugarfoot Rag,” and even a song by Reno’s 84-year old grandmother, “My Sunshine Home.” It was not surprising that Tommy got as a replacement for Verlon a young steel guitar player named Jackie Phelps. Remus Bell played bass. The band was busy: they had a morning show from 6:05 until 7:00, and a 15-minute noon show for Dr. Pepper. Each Saturday night they played at the El-Tenedore Skating Rink on Highway 221 near Floyd, Va., where they had both round and square dances. They also played at a tent show. “If we went too far out of town,” Remus Bell noted, “I know several times we had to record” so the station would have something to play for their shows.

It was this band that traveled to Cincinnati on March 6,1951, to record what would be Tommy’s last records. They were done in the old King studios, but for release on the subsidiary Federal label. Under the name Tommy Magness and his Tennessee Buddies, the group cut four gospel songs that had all been penned by Reno (three of which had appeared in the Buddies’ 1950 songbook): “When I Safely Reach That Other Shore,” “Little Country Preacher,” “Wings Of Faith,” and “Jesus Will Save Your Sold.” Most were done as gospel quartets, and none had a note of Tommy’s fiddle. Reno recalls that Syd Nathan wanted them done as gospel quartets, and in fact wanted to put Reno’s name as leader of the group. “I said, ‘No,’ we were working as Tommy Magness and the Tennessee Buddies and we were going to stay that way.” Tommy, after all, was the one who had the contract. Tommy agreed not to fiddle, suggesting he sing bass, as he had done so often with Monroe. But again, producer Nathan stepped in; he didn’t want Tommy to sing, so he finally wound up playing the bass fiddle. It was an odd session: a first for the duo that would become Reno and Smiley, the last for Tommy Magness.

As it turned out, Reno and Smiley enjoyed singing together and shortly after the Federal session they left to work with a Wheeling, W. Va.-based entertainer named Toby Stroud, and by January 1952, they had formed their own band. Tommy replaced Reno with a local player named Johnny Vipperman. But the group found themselves up against some new and formidable competition: in 1952 WDJB hired the hot new band of Flatt and Scruggs for a six-month engagement, and their popularity ate into the booking possibilities of the Tennessee Buddies.

There were other problems as well. About this time Tommy and the Buddies were involved in a serious car accident; Tommy had been asleep in the back seat, and in the crash he landed on a piece of luggage and injured his spine. A couple of surgeries were necessary to try to repair the damage, but neither was successful. His wife Vada (or Tootsie) had for some time been urging him to get out of music, and now she redoubled her efforts. “My stepmother hated him playing music,” recalled Tommy’s daughter. “That’s one reason why he didn’t go further when he was in Virginia.” Gradually Tommy cut back on his music and began driving a truck for a local transport company. Then, about five years after the car wreck, his wife died suddenly. This depressed him even more, and he had the first in a series of strokes—strokes that eventually caused a numbness in his hand and seriously affected his playing.

About 1958 he returned to Mineral Bluff and remarried, to a local woman named Leah Barnes. By now his professional career was over, though he occasionally would play with local friends and neighbors. At one time, Bill Monroe visited his old friend, and tried to hire him to go with the Blue Grass Boys and play bass fiddle. Tired of traveling, and not at all confident in his ability to even play bass up to Monroe’s standards, Tommy refused. There were more strokes, and more back surgeries, and soon it was hard for him to walk. The strokes were what hurt him, recalled Leah. “It hurt him so bad, because he had played the fiddle so good, that he wouldn’t even pick it up and try to play it.” But there were moments of the old power; one of his last appearances was when he played a dance at nearby Ducktown. But then, on October 5, 1972, he suffered a heart attack in his sleep and died without waking. He was only 56.

There was no great public notice of Tommy’s death, but he had already achieved a legendary status among musicians. The next Saturday night at the Opry fiddler Taler Tate approached a guest and said, “Tommy Magness has died. I know you’ve heard that he died several times before, but this time he really died.” His daughter reflected: “They say Tommy’s fiddle playing was 20 years too early. Now Benny Martin and Richard Greene do it— on their LPs you can hear the sound of Tommy Magness.” In many ways he was a musician’s musician—one of the great stylists who never made it in the public eye—indeed, who never really had an album under his own name. But Tommy Magness was also a vital link between the older mountain music and the newer bluegrass, and his spirit lives on today in the work of dozens of fiddlers who never met him or heard him in person and know of him only as one of the more potent of legends.

NOTE: While there has never been a reissue album devoted to Tommy Magness’s work, he has been fairly well represented on CD and LP. The great sides with Roy Hall were reissued on a County LP, “Roy Hall And His Blue Ridge Entertainers.” A complete 1942 radio show featuring Tommy and Roy Hall, as well as a 1947 show with the Orange Blossom Boys, were issued on an LP by the Blue Ridge Institute (BRI 010), “Early Roanoke Country Radio.” Magness’ entire output with Bill Monroe is on a CD entitled “Mule Skinner Blues,” RCA-BMG 2494-2-R. Some of the better sides with Roy Acuff, including “Black Mountain Rag,” is on a CD called “The Essential RoyAcuff,” Columbia/Legacy C.K 48956. The early sides with Reno and Smiley are included in the recent King boxed CD set of the duo’s work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Special thanks to Gene Wiggins for sharing his interviews with Lena and Leah Magness; to Faye Magness Harris; to Bashful Brother Oswald; the late Bill Monroe; Kip Lornell; Ivan Tribe; and Elizabeth Schlappi.

The author of 16 books on country and bluegrass music, Charles Wolfe is a professor at Middle Tennessee State University near Nashville. His latest book is a biography of the Lanvin Brothers and he is currently working (with Neil Rosenberg) on a book entitled THE MUSIC OF BILL MONROE.