Endless Fields of Bluegrass

The Colorful Origins of the Songs of Bluegrass Music

Bluegrass roots run deep. Many of the songs picked and sung on bluegrass stages predate the band members by generations. Several sailed across the ocean with the early immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland. As settlers ventured out from Jamestown and nearby villages, some headed toward the Appalachian Mountain country of modern day Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and the Carolinas. The story-songs they carried in their heads soon rang out through the mountain air of their new country and reminded them of the people and places in their motherlands.

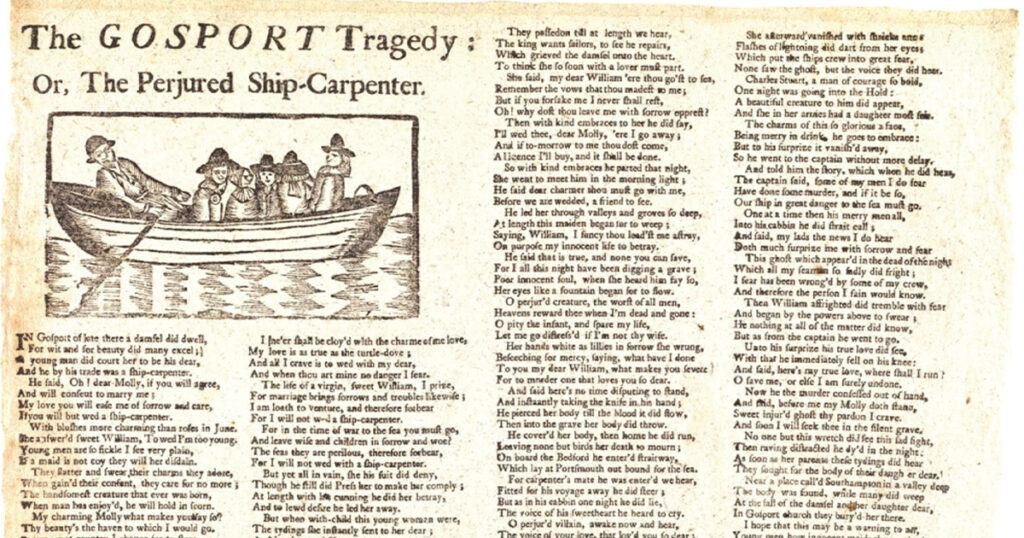

A sorrowful old English classic with the, then-traditional, double title of “The Gosport Tragedy or the Perjured Ship Carpenter” first appeared as a broadside in the 1700s. Broadsides were cheaply produced sheets of paper printed on only one side. Ultimately transforming into “Pretty Polly,” the original ballad is thought to be based on an actual murder in 1726. John Billson, the carpenter aboard the M.M.S. Bedford, was accused of killing his pregnant girlfriend, Molly Hurwitz, and burying her in the woods before he headed off to sea.

Exhibiting a good dose of karma, Molly’s ghost later visited him aboard the ship, holding a ghost baby in her arms—and eventually drove Billson into madness. In another version, John, who in that broadside was called “William,” was not the guilty party. According to that account, the actual murderer, Seaman Charles Stewart, confessed to the crime after seeing the ghosts of Molly and her baby. Either way—and despite a name change to “Polly,” poor Molly certainly didn’t ghost The Stanley Brothers, The Dillards, The Coon Creek Girls, and the others who snooped around for a good old murder song to record.

The fiddle standard, “Leather Britches,” first recorded by Tennessee’s Uncle “Am” Stewart in 1924, dates back under various titles to “Lord McDonald’s Reel” published in an English song collection in 1792. The later title, “Leather Britches,” according to many bluegrass history buffs, refers to the age-old nickname in the South for dried green snap beans. After the beans were strung together and dried in the pod, they looked like cured leather—but could be revived by boiling them along with a tasty chunk of pork.

Despite the mountain folks’ preservation of the ballads of their mother countries, it wasn’t long before they created songs about their newly adopted homeland. They often fused old melodies to fresh lyrics about the cabins, farms and families of their new home. The melody of the bluegrass standard “Shady Grove,” for example, is nearly identical to that of an old English balled titled “Little Margaret.” And “Roving Gambler,” supposedly written about a traveling gambler in early America, likely descended from the 1820’s Irish broadside ballad, “Roving Journeyman.”

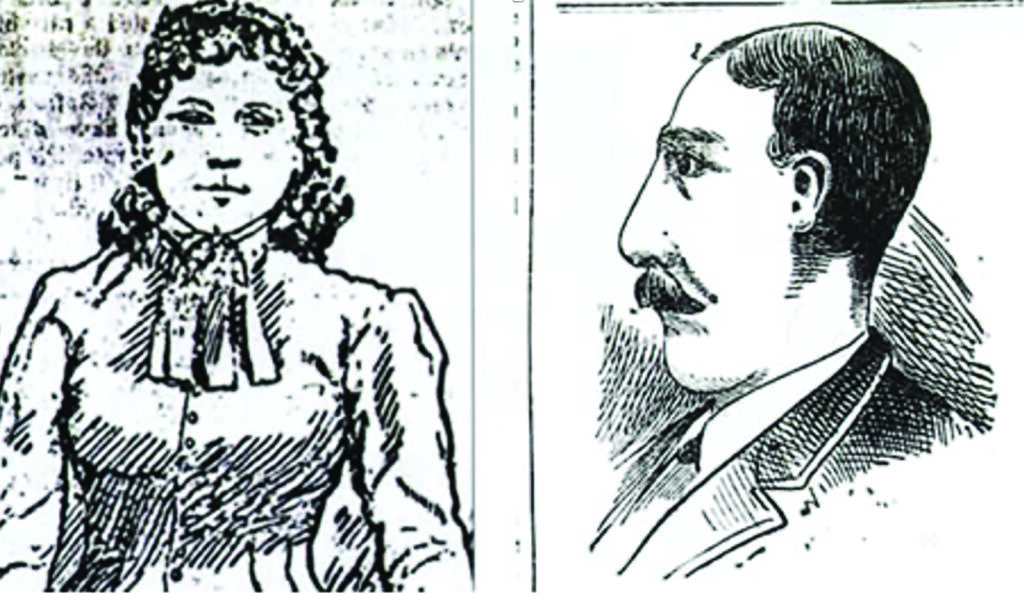

Like their predecessors in the old countries, some of these newborn lyrics served as “singing newspapers” of the day. Traveling singers often wrote and sang about tragic accidents, natural disasters, and violent crimes they encountered along their circuits. Another infamous murder ballad, “Poor Ellen Smith,” details the brutal 1892 killing of Ellen Smith by a ne’re-do-well named Peter DeGraff in Mount Airy, North Carolina. Along with a host of other sorrowful musical tales like “Knoxville Girl” and “Banks of the Ohio,” “Poor Ellen Smith” helped impart an eerie quality to the growing collection of mountain songs.

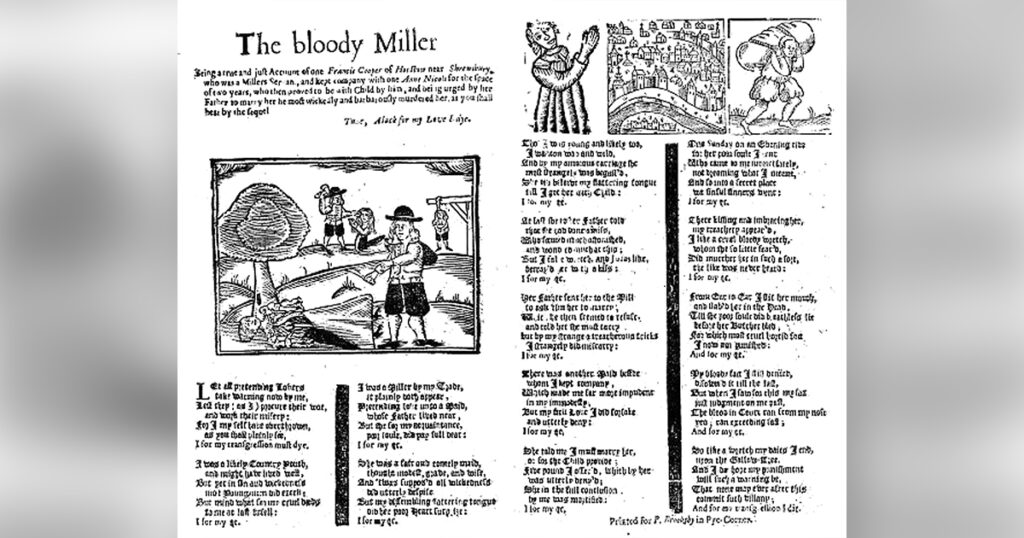

The “Knoxville Girl” murder incidentally, although supposedly occurring in Tennessee, was based on the 19th-century Irish ballad “The Wexville Girl.” And that song was derived from an old English ballad with the double title of “The Bloody Miller or Hanged I Shall Be.” The original tale springs from the 1683 murder of Anne Nichols by mill apprentice Francis Cooper, south of Shrewbury, England.

All the versions—which include the “The Oxford Tragedy,” “The Wittham Miller,” and “The Berkshire Tragedy,” incorporate the scene in which the killer develops a severe nosebleed upon returning home. Poor Anne Nichols’ demise, like those of Ellen and Molly, seems to have given the world a lot of lively picking and singing. But nowadays songwriters and female country singers have evened the score with a slew of songs like, “Independence Day,” “Gunpowder and Lead,” and “Goodbye Earl.”

The shape-note music teachers, who traveled the Appalachian region in the mid-1800s, added more songs to the growing bluegrass repertoire. Their easily read music books utilized basic shapes on the bottom of the notes, and emphasized harmony singing. As mountain musicians learned the simplified method of singing harmony to the melody, they transferred the process to their secular tunes as well. Now-classic numbers like “Keep on the Sunny Side” and “This Little Light of Mine” were born during the shape-note times.

The traveling medicine shows also had an impact on the developing Appalachian music scene. While the silver-tongued medicine show “doctors” proclaimed the instant cures from their magical tonics and elixirs, the show’s entertainers offered songs borrowed from repertoire theater companies, vaudeville and variety shows. Songs like “The Preacher and the Bear” and “Cripple Creek” rang out through the mountain air from the medicine show wagons and truck-beds, as the professors and doctors peddled their snake oil liniments and blood purifiers.

The building of the railroads widened the horizons of the mountain musicians. As steel rails stretched across their once-secluded world, they began to hear the songs of the African American railroad workers. Little by little, the mountain musicians incorporated some of the workers’ bluesy tunes and rhythmic work chants. The often-played bluegrass standards, “John Henry” and “Nine Pound Hammer” both sprang from the songs of the early railroad laborers.

Year by year, the music of the mountains simmered and bubbled into a distinctive musical brew like none other in the world. As the outside world slowly seeped through the mountain barriers, further ingredients entered the recipe. The parlor songs that had become popular after the Civil War added tunes like “Wildwood Flower,” “If You Love Your Mother” and “A Song of the Hills.”

Vaudeville and other variety shows also supplied their songs. As the numbers that filled their shows became popular, publishing companies printed song sheets by the thousands. A section of New York City’s 28th street developed into the heart of the songwriting and sheet-music publishing empire. Its nickname “Tin Pan Alley” came from the mingled sounds that poured through the open windows as the song promoters played pianos in various keys and tempos.

Many of the songs that came out of Tin Pan Alley were tearjerkers about displaced family members longing for their old home place. The mountain boys who had left home to find work in the city often sought comfort in them. Songs like “I Wonder How the Old Folks Are at Home,” “My Old Plantation Home” and “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” could bring a tear to the eyes of even the toughest steel-mill worker.

The now-controversial minstrel shows also added songs to the mix that would one day pour from bluegrass stages across the country. Currently viewed with distain due to its outrageous racial stereotyping, the minstrel show could once guarantee a packed crowd to any opera house in the land. Songs like “Turkey in the Straw,” “Watermelon on the Vine,” and “Arkansas Traveler” all sprang from the minstrel stage.

The most ironic minstrel song is the one written by Daniel Emmett for the finale of his minstrel show. Emmett sat in his New York City boarding house and wrote the song “Dixie’s Land”– soon shortened to “Dixie.” Actually, he never saw the South a day in his life and was a staunch Union supporter. He was not exactly thrilled when he learned Confederate soldiers were marching to it during their drills and battles. “If I had known to what use they were going to put my song,” he once lamented, “I will be damned if I’d written it!”