Home > Articles > The Archives > Eddie and Martha Adcock — Finding Their Place In Bluegrass Music

Eddie and Martha Adcock — Finding Their Place In Bluegrass Music

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1982, Volume 16, Number 10

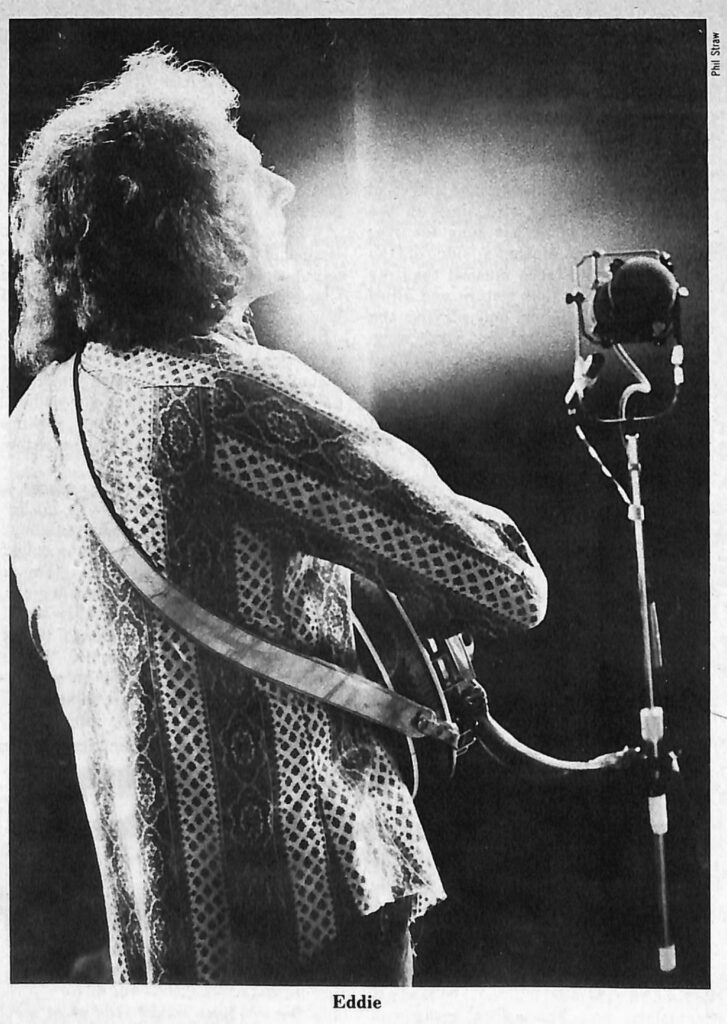

It seems the bluegrass music world just doesn’t know how to take Eddie and Martha Adcock. They cross the lines between bluegrass, folk, country, rock and jazz like few other performing units on the bluegrass festival circuit.

Eddie Adcock deserves a place in a bluegrass music Hall of Fame due to his many contributions to the acoustical, down-to-earth form of musical expression. He has been in the bands of the best: Bill Monroe, Mac Wiseman, Bill Harrell, Buzz Busby, The Country Gentlemen and his own II (Second) Generation. His banjo and guitar work are of the finest degree of quality and have been much copied.

Adcock also popularized a bluegrass standard used by many young groups playing nightclubs and festivals. The song reflects a lot of the hard times Adcock has seen in attempting to make a living out of bluegrass music.

He sings in “Make Me A Pallet On Your Floor” a low feeling shared by many with the words, “Blues all around me. They’re everywhere I see. Nobody’s had these blues like me.”

He also sings in that song about fickle friends who only support you in your better days by observing, “Come on all you good-time friends of mine. When I had a dollar you treated me just fine. Where’d you go when I only had a dime?”

Some traditional bluegrass music fans, however, have a problem with Adcock. They seem to think he should stay the way he has been for many, many years instead of experimenting with rock and jazz sounds as recorded on his recent albums. They like his acoustical playing but not his electric guitar.

Adcock told writer Robert Kyle for an article in Washington, D.C.’s, Blueprint newspaper, “I love bluegrass, and I love bluegrass people, but they aggravate me to think that they can go out and have them a good job and make big money and put money in the bank and drive fine car around…but tell me that I can’t do what they’re doing. I’m not allowed to have any money. I’ve got to play bluegrass or else. They just don’t understand that I like bluegrass, but I’ve got to eat, too.”

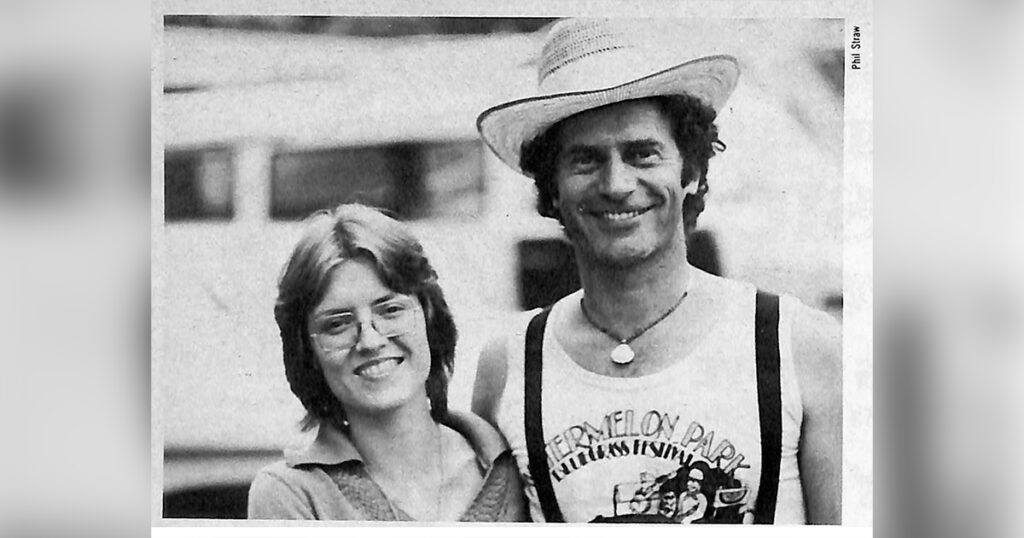

The Adcocks bubble with personality. They sparkle with charm and creativity. They are warm and loving, and they deeply care about bluegrass music and their fans.

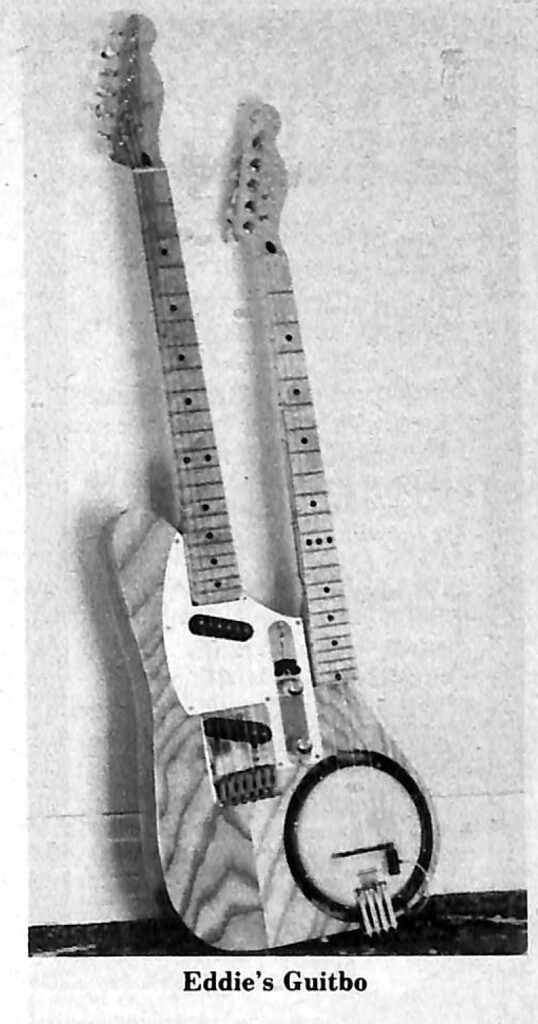

Eddie doesn’t just play a guitar or a banjo like “normal” bluegrass music musicians. He plays a “gitbo” which is a special instrument he invented about two years ago. It looks like a double-necked, electric guitar with a banjo head buried in a lower corner. Just by flicking a switch, Adcock can make that thing sound like either a banjo or a guitar. You just know Uncle Dave Macon wouldn’t have been caught dead with one of those things. Then again, knowing Uncle Dave’s love for entertaining, he just might have played a gitbo if one had been around.

If their style of music, their going on a stage as a duet act and their gitbo aren’t enough to set them apart from your usual bluegrass music acts, the Adcocks don’t travel with a nice dog like some bluegrass teams. They travel with a cat! They even have posed with their cat for at least three of their album covers! You wouldn’t catch Bill Monroe posing with a cat, although the Father of Bluegrass Music has been photographed on the back of a bull.

Martha says of their cat, “Poopsie has traveled more than a half-million miles with us. He was conceived in LaFayette, Louisiana, and born in Nashville.” Although Martha doesn’t say it, this obviously makes Poopsie one of those “Nashville Cats” The Lovin’ Spoonful used to sing about. Almost at any given bluegrass festival while the Adcocks are performing, Poopsie can be seen sleeping on the dashboard of the Adcock’s motorhome.

Poopsie wasn’t in too great a mood, when I boarded the Adcock’s motorhome at the first Red Hill, South Carolina, bluegrass festival held near Edgefield. The part-Siamese was ticked-off that I had left my minature Collie, Foxie, only a short distance outside the door of the Adcock’s coach. Poopsie, in spite of assurances by Martha that my dog was friendly, kept staring out a window and making warning sounds.

With Poopsie finally quiet, the Adcocks talked about the musical background and how they came to be a husband and wife team.

Eddie was born in Scottsville, Virginia, in 1938. His handsome looks and powerful physique, however, make him appear to be years younger. He became interested in banjo playing after his brother, Bill, brought a tenor banjo into the family household but didn’t play it. Eddie took it over. Later, Adcock’s mother gave him a calf, and he raised it, sold it and used the money to purchase his first five-string banjo, which was an RB-150.

With another brother, Frank, Adcock began performing gospel music at local churches and over stations WCHV and WINA in nearby Charlottesville. Joe and Wesley Smith joined the Adcock brothers to form the James River Playboys, so named after the river that flows past Scottsville.

Before learning the banjo, Adcock had experimented with the guitar and mandolin. He notes, however, “The banjo was the first instrument I took seriously.” His guitar playing had been influenced by the likes of Les Paul, Hank Williams, Joe Maphis and Merle Travis.

He was very aware of performing and playing styles from an early age when he got a job pulling the curtains at the Victory Theater in Scottsville. He recalls, “I saw just about everybody who was on radio then including The Bailes Brothers and also Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper.”

Besides learning how to work odd jobs at an early age, Adcock also learned a lot about life. He related, “I left home when I was 14, and I never went back. My daddy had cancer, and he was supposed to die within a few years. He lived 17 years beyond what he was supposed to have lived. I was helping support my family at an early age. I was working the farm, shucking corn and doing other farm chores.”

Adcock learned how to become a survivor. He took one odd job after another in order to stay in the music business and keep playing the music that he loved.

“From about 15 to 22, I boxed semi-professionally, and I had a lot of fights. I got into drag racing for awhile, and I had 34 straight wins. My car was called ‘Mr. Banjo.’ I set two track records at Manassas, Virginia, where I got in a wreck and broke my arm. I set another record at another place in Maryland, racing in the Double-A, Modified class.

“At various times, I was an auto mechanic, a heating and air conditioning repairman, a sheet metal worker, a laundry deliverer, a dump-truck driver, an auto parts salesman, and the owner of my own gas station.

“I even had a four-and-a-half hour Saturday television show for three months in Norfolk, Virginia. I was the announcer and singer, and I did live commercials for such products as wigs and hair spray. All those jobs I’ve named were more on the side than career work. I did them, because I couldn’t survive just by playing music in those days.”

There’s no question that with all the festivals in America and through nightclub work, Adcock has a much better chance these days of survival doing his music full-time.

After his early gospel music work, Adcock took a job at the age of 15 in 1953 with Smokey Graves and his Blue Star Boys at WSVS radio in Crewe, Virginia. That led, after a recommendation from Don Reno, to working a year with Mac Wiseman and his Country Boys.

His next music job was with Bill Harrell and the Rocky Mountain Boys in Maryland that lasted until Harrell went into military service and the band broke up.

Following Harrell, Adcock found himself in Washington, D.C. playing guitar with Buzz Busby and his Bayou Boys. That ended on July 4, 1957, when a serious car accident sent him to the hospital for several weeks.

He was 19 years old in 1957 and a seasoned veteran when Bill Monroe called him at another off-music job: Working as a janitor at a high school in Annandale, Virginia. He put down his broom, took up his banjo and hit the road again.

Being a Blue Grass Boy at that time was not as glamorous as it may seem today, Adcock observes. He added, “I was with Bill for about six months at a time when he wasn’t drawing flies. That’s not to say anything bad about him, because all of bluegrass music was rough then. We worked some places that didn’t even have floors. Sometimes, I went two or three days without food. I helped Bill on his farm also. We would work six to eight hours during a day, and then we would go do a show that night.”

After the time with The Blue Grass Boys, the still youthful Adcock decided being on the Grand Ole Opry with Monroe wasn’t the life of a star he wanted, and he got off the road and took another normal job as a sheet metal worker.

“I quit music, and I decided I wasn’t going to be hungry anymore. I barely had scraped [together] enough money to take the bus home. The Country Gentlemen wanted me to go with them, but I didn’t care to go back on the road. Jim Cox, John Duffey and Charlie Waller stayed the best part of one night begging me to join them. When I said, ‘yes,’ I hated myself.”

Adcock stayed with The Country Gentlemen for 12 years and changed the musical direction of the group. He influenced them to search for original material and this search for songs brought new life to The Country Gentlemen.

After more than a decade, however, Adcock was ready to try something new. He headed to California where he started a country rock band and performed under the name “Clinton Kodak.” He was playing loud, electric, fuzzy guitar, but he missed the East Coast life and moved back.

Around 1971, Adcock created the II Generation group with Jimmy Gaudreau, Bob White and Wendy Thatcher.

Martha Hearon came into the picture in the spring of 1973 and became a member of II Generation in the fall of that year. Her primary background had been with classical and folk music.

She had been born in South Carolina and grew up in Bishopville, near Florence, as part of a farming family. “My father farms 3,000 acres of cotton, tobacco and soybeans. He is a fine singer and musician himself, and he majored in music at the University of South Carolina where he was with the Glee Club. Kay Kyser tried to hire him in Chicago, but he wanted to finish school. World War II, though, broke out, and, since his older brothers were gone, he left school and returned to the farm. He felt it was his responsibility. So, he gave up his singing career. I feel he could have gone places. He has a beautiful baritone,” Martha related.

She continued talking about her father noting, “He plays piano and used to play the sax. He still sings in the church choir, and he has sung for over 1,000 weddings. Mother’s side of the family was even more musical than my father’s. She has four sisters and all of them enjoyed singing and playing the piano. Mother and Dad met while singing. I think that’s very romantic. Dad was dating her older sister, and they asked mother to play for him to sing.”

Speaking of her family’s musical background, Martha also observed, “My grandfather —my father’s father —was an excellent fiddle player. My parents, though, got into light classical and pop music. I came around to old-time and bluegrass music through being interested in folk music in the 1960s. I got gradually more and more sucked into bluegrass music, and I eventually traded a Martin classical for a Martin steel string. I was a finger picker, and I switched to a flat pick so I could play lead.

“One day I was driving through Charlotte, North Carolina, and I stopped in C.E. Ward’s shop. Later, I started doing inlay and repair work for him. That led to Nashville and doing inlay work for Randy Wood at the Old Time Pickin’ Parlor. It was an exciting time there, because people always were coming in and jamming; people like Norman Blake, Vassar Clements, Buck White and Leon Russell. It was sort of the Left Bank of Nashville.

“While working there, I met Eddie. He had II Generation at the time, and the day after we met he took me to Clarksville, Tennessee, where his band was performing at a college.”

Shortly after they married, the Adcocks purchased 15 acres on the side of a mountain near a big lake about an hour’s drive east of Nashville. They moved back to Tennessee in 1980 after making Maryland their headquarters for a few years.

Although their land in Tennessee is a home-base, Martha and Eddie go different ways in their song writing about life on the road. Eddie, for a song called “Bound To Ride,” observes, “I’m a travelling man. My restless soul is going to keep me rolling all over this land.” Martha, however, in her song “Going Home in the Rain” comments, “Home through the mountains in the rain; hearing the wipers singing home, home again. Interstate signs all look the same.”

Besides singing, playing guitar and writing songs, Martha also writes a quarterly newsletter for fans of II Generation. Some samples from that newsletter give a good indication of the kind of life Martha and Eddie have been living lately:

- “The reunion concert at Lisner Auditorium in Washington, D.C., was a smashing success. Several thousand fans came; some from as far away as New Brunswick, Canada, to hear Eddie and Martha Adcock, The Country Gentlemen and the reunion of the Original Country Gentlemen with Eddie Adcock…

- “Guitar Echoes,” Eddie’s instrumental album, is going great. Reviews have been very favorable. CMH Records has received airplay reports for ‘Guitar Echoes’ from stations all across the nation.

- “The Gitbo is capturing the imagination of the public. Eddie previewed the new instrument on Valentine’s Day at the Elbow Room in Harrisonburg, Virginia, and since then it has caused considerable interest.

• “The cruise aboard the S.S. Rotterdam was truly fantastic! And of course it was a pleasure performing in company with Mac Wiseman, Bill Anderson and Jeannie C. Riley on the jaunt to the Bahamas and Bermuda. And Bill Anderson invited us to join his softball teams for the annual tournament in Nashville during Fan Fair Week in June.

- “Two more books have been found to document Eddie and Martha Adcock, II Generation, with hardback respectability: ‘The Illustrated History of Country Music,’ edited by Patrick Carr, and ‘Folk Music, More Than A Song,’ by Kristin Baggelaar and Donald Milton.

- Hundreds helped Eddie celebrate his birthday at a festival in Ripley, West Virginia, singing ‘Happy Birthday’ as a lighted cake was brought onstage in the middle of Eddie and Martha’s concert. The Canadian band, Foxglove, was the thoughtful culprits. They brought in the cake by a specially dispatched motorcycle!

• Eddie was presented a very special belt buckle recently, made by Mr. Danny Gatton Sr. and engraved by him to read: ‘To my good friend, Eddie Adcock, the best banjo player I have ever heard.’ ”

When one reads those items, the obvious conclusion is all those years of working odd jobs and nearly starving in order to stay in the music business apparently were worth while for Eddie Adcock.

Eddie and Martha Adcock may still travel in a motorhome and may be having a rough time making ends meet in these hard economic times, but they undoubtedly are rich in the things that truly matter: The love and gratitude from their feline travelling companion, and the respect for their music and determination that comes from their legions of fans.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I was Bill Monroe’s last Recording Producer when Bill passed away in Sept. of 1996, due to a severe stroke he suffered several months earlier. For years earlier, I was also his Recording Engineer. In June and September of 1994 & 1995 I Produced and recorded on multi-track Bill’s last 27 Bean Blossom shows in June and September of 1994 and 1995. However, these live Bean Blossom recordings have never been released. Kurt Storey, who is the current sound engineer with Michael Cleveland, was the Recording Engineer I used on these unreleased Bean Blossom recordings. Eddie and Martha’s sound company in those years provided the stage sound system and the audience sound system. Eddie and Martha both sat in the audience and mixed the audience sound while an employee they had sat on the side of the stage and mixed the stage sound system for the artists and musicians. Eddie and Martha both in those early years of Bean Blossom provided the sound for Bill’s Bean Blossom Festivals. Also, during each festival Eddie and Martha would always perform their duo act on stage. I remember it was always great working with both Eddie and Martha!

Vic Gabany

[email protected]

My tribute to Eddie.

My treasured photos,

https://frobbi.org/slides/adcock/