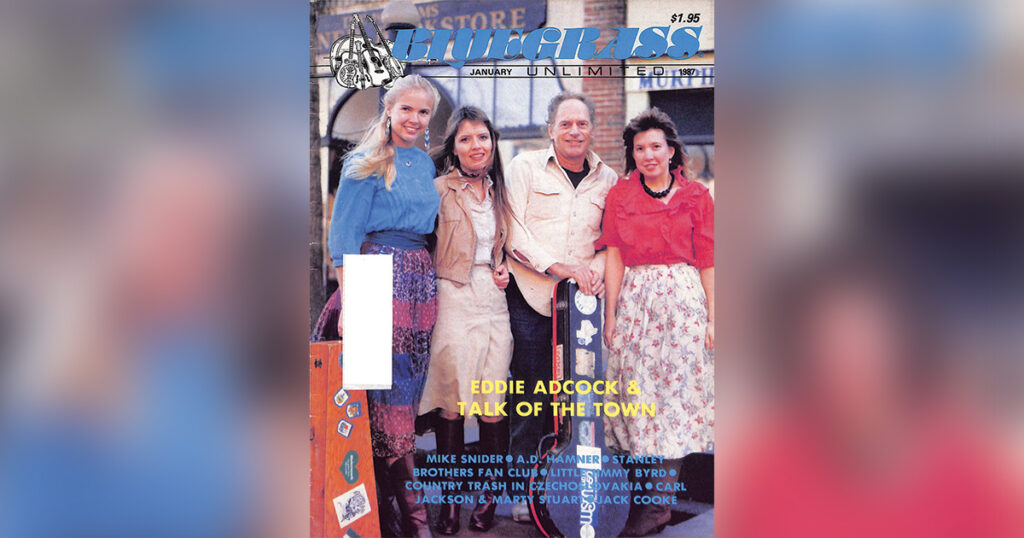

Home > Articles > The Archives > Eddie Adcock and Talk of the Town—Band on the Cutting Edge

Eddie Adcock and Talk of the Town—Band on the Cutting Edge

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1987, Volume 21, Number 7

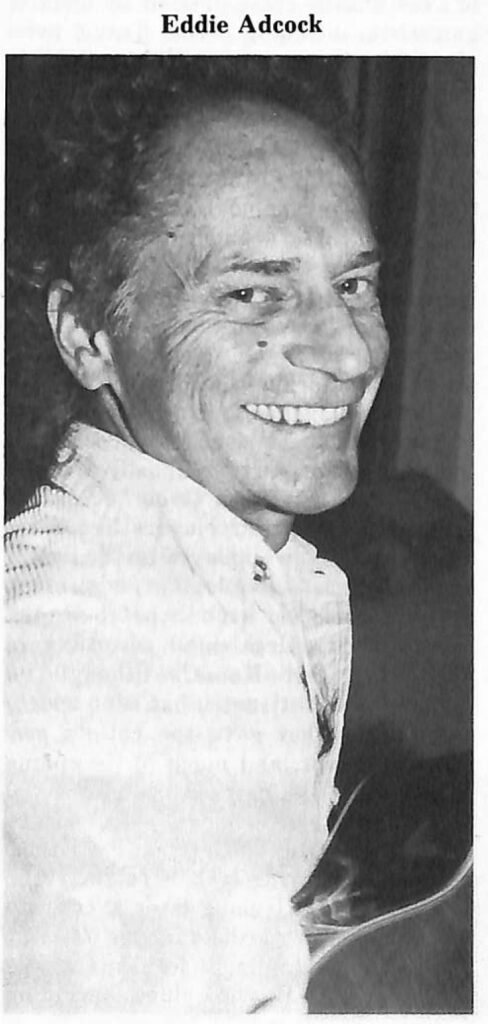

His shoulders are braced back, at the ready, and his sharp eyes peer keenly forward, like a dedicated lifelong explorer who knows with certainty that his greatest discoveries lie just ahead. The muse that adrenalizes his creative genius is a restless one (“I don’t always stay around for the profit”). It has taken him from his days as a pivotal member of the Country Gentlemen (he has been cited by at least one prominent bluegrass historian as the man who brought the sound of that early forward-looking band together, and made it unique), through an interim of country/jazz/rock, to founding the ever-changing, always innovative IInd Generation. He’s come through country music both acoustic and electric, to a year-and-some with one of Nashville’s most prominent singers David Allen Coe, playing an important part in helping him offer one vital alternative to today’s terminal-gray, robotic, ersatz-country Nashville sound. And he may well have been, regardless of what the term may connote today, the first “new acoustic” musician. He is Eddie Adcock, and with surpassing talent, creativity and what he calls the “want-tos,” he has always done, in the fullest sense of the phrase, what he needed to do. He has been a professional musician for more than thirty years (that’s all I ever wanted to be”), making his often quixotic decisions from a pure base of creative motivation and perplexing a number of career-oriented observers in the process. Now, at a time when many of his peers seem bent only on feathering their ruts, Eddie has made another decision that will assuredly aesthetically enrich his niche. That decision is a new, four-person acoustic group called Talk Of The Town.

Often, in a present-day society where mass communications show every body everything, heretofore self-contained musical types and styles find themselves mere fodder for today’s fashionable fusions, like a former headliner who latterly finds himself an opening act. In these fusions, vital ingredients become so homogenized that they are no longer recognizable, let alone meaningful. Eddie Adcock, too, draws ingredients from a wide variety of occasionally unexpected sources, and like today’s modish fusioneers, pours them all into his musical crucible. By contrast, what emerges is not some stillborn narcosis, but creatively dynamic fission, joyously alive, all its ingredients still emphatically present, and the whole somewhat greater, even, than the sum of its parts.

From the beginning, Eddie Adcock has approached his music in his own way. He learned early that anyone with the motivation to be unconventional poses at least a tacit threat to the staus quo so cherished by the usually less gifted. (He who is not “going along with the program” may simply be tuned in to a better program.) At the time his brother Bill brought home the banjo on which Eddie first started to learn, the war was on, and batteries for radios were scarce, so Eddie began to play without any knowledge of what the music was supposed to sound like. He found, after hearing some of the early greats, that it was difficult for him to copy anybody—it was “easier to do what I’m doing than to go out and learn what anybody else is doing, so I kind of stayed with my own stuff that was rolling around in my head.” At first, he did not have the basic roll right, but soon, at Crewe, Virginia, Eddie met Don Reno, who “gave me the first set of picks that I had, and showed me the roll.” Eddie’s regard for Don (“he was my favorite banjo player”) continued throughout Don’s career; their strong musical kinship resulted in the delightful, imaginative 1968 Eddie Adcock—Don Reno LP for Rebel, an album that was done in just a few hours, with no rehearsal, and with tunes chosen on-the-spot in the studio. Eddie notes that the musical dialogue between these two good friends was, perhaps surprisingly, indeed an exchange. “At the time Don showed me the roll, he also absorbed the fact that I was playing single-string—that’s all I was doing in 1955. Don’s single-string (picking) developed from watching me play quite often—many nights we jammed all night together.” Their musical kinship has another dimension, too. Eddie has always felt that Don was even more a guitar player than he was a banjo player, and “that shows up in my banjo playing—I was always really a guitar player, in every sense of the word, because everything I was trying to play on the banjo was guitar.” (Interestingly, when Reno was asked if he was upset that, by the time he returned from service, Earl Scruggs had the job that Bill Monroe had offered Don two years earlier, he replied that he wasn’t, because he was “more interested in guitar at that time.”)

As far back as the mid-1950s, long before cross-pollinations of musical styles became first a new thing to do, and then the commonplace thing to do, Eddie was listening to and absorbing the work of a fascinating cross section of electric guitarists, including Merle Travis (who played both acoustic and electric), Les Paul (“I was trying to play the stuff he used eight tracks for”), Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland, and Jimmy Bryant. “Sugarfoot Rag,” the tune that gave Garland his nickname, has always been a favorite of Eddie’s, and is in the working repertoire of Talk Of The Town. The Nashville-based Garland received more recognition (he even released two jazz LPs on a major label in the early 1960s) than the California-based Bryant, but Eddie has equally high regard for them both—“Speedin’ West,” a concoction of Bryant and his partner Speedy West is on the Adcock-Reno Rebel LP. Progressive steel guitar players like West and Bud Isaacs, who played on the first C & W hit record employing pedal steel, caught Eddie’s ear back then, too. On the 1959 Country Gentlemen recording of “The Hills and Home,” although its theme was traditional, it has been widely noted that what gave the cut its progressive flavor, and much of its unique “Gentlemen” sound, was Eddie’s pedal steel-oriented banjo break. Well before he joined the Gentlemen, Eddie remembers playing rock ’n’ roll on stage at Berryville, Virginia, later a favorite festival stomping ground for the Country Gentlemen, and filling in for Roy Clark in Washington D.C.-area clubs, including the Country Gentlemen’s subsequent second home, the Shamrock. But always, including his 1971 California stint as Clinton Kodak, when Eddie played electric guitar, he played under a pseudonym, so that aspect of his musical genius is still a “secret” to many of his most ardent admirers.

While all the guitar and steel guitar influences were fermenting, Eddie was also listening to the early greats like Scruggs, Reno, Ralph Stanley and Allen Shelton. In a reversal of the usual geographic flow of bluegrass musical influence, the southern-born Eddie was also listening to and appreciating the work of such northern banjo luminaries as Winnie Winston, whom he recalls as admiring for years, and whom he regards as an important contributor to what became the Keith style, and Eric Weissberg. In many ways, Weissberg was Adcock’s northern counterpart—he was open to many progressive influences, he was proficient on more than one instrument, his approach was always athletically dynamic, and, as Eddie recalls, Eric fashioned his own style without undue regard to what others were playing.

Top banjo pickers like Don Reno and Allen Shelton were adapting non- bluegrass and non-country tunes to their styles-within-a-style in the 1950s, and Shelton even played steel-oriented banjo breaks on country/bluegrass vocal dance tunes. But, Eddie Adcock, in playing tunes like “The Poor People Of Paris” in the 1950s, and “Exodus” when the movie first came out in 1961, as well as his work on tunes like “The Hills And Home,” was among the first, if not the first to propel the banjo toward an entire new style. As such, Eddie may well have been the first “new acoustic” musician. Of course, the phrase has only lately come into vogue (see BU/November, 1985), and it seems to connote an elite form of string music, the emphases of whose sophisticated, virtuoso dynamics are urban, bi-coastal and cerebral. By contrast, the sophisticated, virtuoso dynamics of Eddie’s music, no matter how complex that music becomes, are always direct, southern and visceral—Eddie Adcock is an unabashedly extroverted country musician. “I think ‘new acoustic’ means you can be like the IInd Generation—it means you don’t have to play bluegrass, you can still keep your acoustic instruments and play other music.” At a time when no one else was playing the part of Eddie Adcock’s music within the bluegrass framework was certainly acoustic, and definitely new. No less an authority than Sam Bush, himself a great originator of progressive acoustic music, has said to Eddie, “You started it all!”

From his earliest days with the Country Gentlemen, Eddie has also been literally a standout baritone singer. The trio was less prominent in the original bluegrass sound than in more contemporary bluegrass styles, and often the baritone voice was almost inaudibly “hidden” in the blend. The Osborne Brothers ushered in a new era in the latter half of the 1950s with their emphasis on trios, especially those with the high lead featured, and the Country Gentlemen were among the first to follow in their footsteps. Unlike the many and varied influences on his instrumental work, Eddie acknowledges just one influence on his baritone singing: Bluegrass Unlimited owner/editor-in-chief Pete Kuykendall, Eddie’s predecessor, occasional substitute and occasional twin-banjo picker with the Country Gentlemen. “A lot of the little twists and turns I have in my own voice now are just from hearing him, and being around him …” In those days, Eddie recalls, “I’d spend a lot of time just singing baritone —I wouldn’t sing any other part. I’d sit at home and sing every song the Country Gentlemen did [by myself]. I feel baritone is as natural as breathing—it sounds like the real tune to me.”

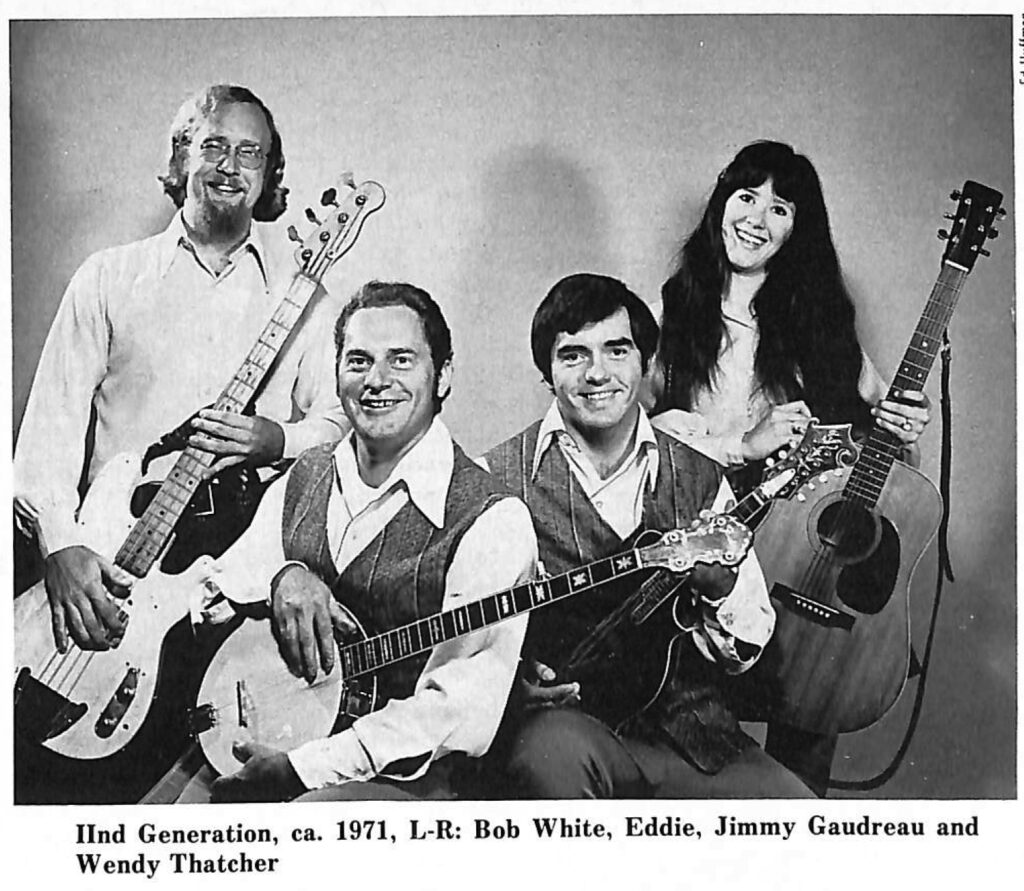

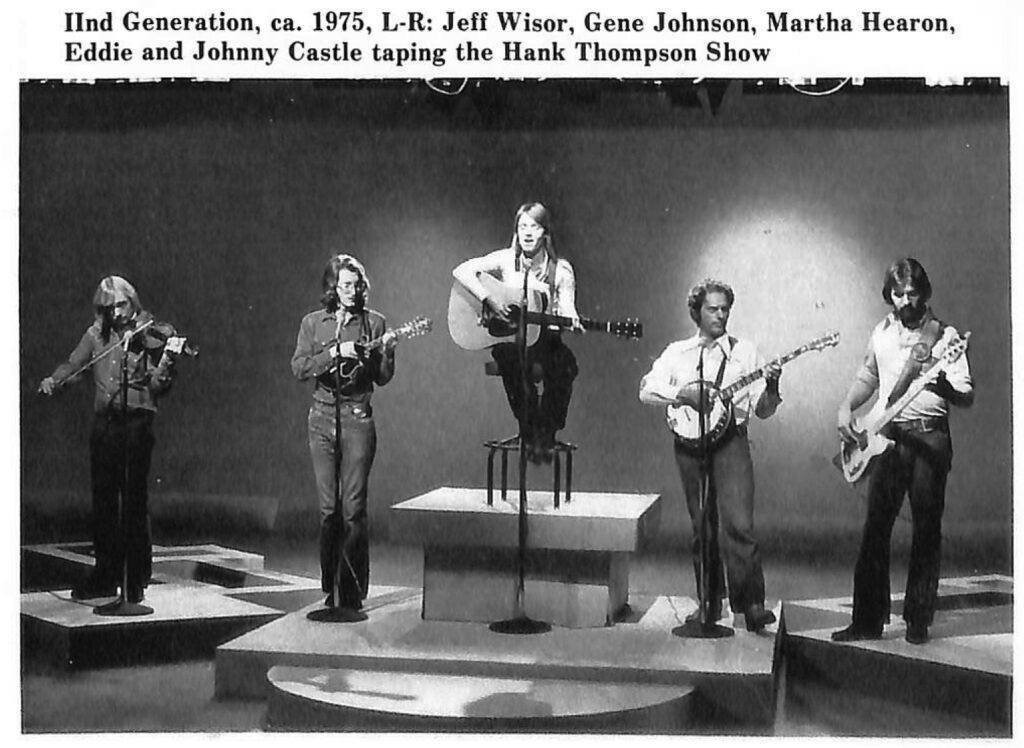

Although the sound of Talk Of The Town is joyously fresh and vital, this is not the first band Eddie has formed. A chance encounter with Jimmy Gaudreau, then of the Country Gentlemen, at Bill Monroe’s Bean Blossom Festival in 1971, while back from California “just to hear some bluegrass” led to the formation of the IInd Generation. The band included the bass player from another pioneer progressive group, the New Deal String Band, Bob White. It also included a young Tony Rice, who, Eddie remembers, “spent all the time it took to work up all the material, and then went with J.D. Crowe the night before our first show.” Wendy Thatcher took Tony’s place, quickly learning all the material. The band soon became one of the top attractions on the bluegrass circuit, playing top festivals and as many as fifty- seven colleges in one year. “We were making so much money,” Eddie laughs, “I didn’t think we were still playing bluegrass!” There was a steady turnover in personnel; the band also fluctuated in size, at one time numbering as many as seven. Looking back, Eddie feels the best IInd Generation was the group that contained Gene Johnson, Jeff Wisor, Johnny Castle, Martha Hearon (Adcock) and himself. But, like a scientist who sees that his experiment has worked out, and is impatient to get to the next one, Eddie was again restless. “I was finished, done [by the time] I’d made it in bluegrass [with the IInd Generation]. I had to go out and re-program myself with other things in order to be able to come back and move the music on some more.’ He needed to start over, and characteristically, he didn’t care what it cost. I made less than a thousand dollars my first year in country. There’s no way to get into country without someone that’s already in it bringing you into it—its just closed doors.”

The change in musical approach also brought a change in record labels. Eddie has always felt that the IInd Generation’s three fine LPs for Rebel (1974-77) were under-promoted by that label under its former ownership. (As a possible example of prevailing conditions there, although the IInd Generation’s version of “Gold Watch And Chain” was apparently recorded though not issued before Ralph Stanley’s, the IInd Generation “Head Cleaner” LP, the traditional, public-domain song is credited to “Stanley” as writer!) “CMH immediately started spending money on promotion,” says Eddie, “and selling records.” Eddie and Martha’s four albums for CMH encompassed bluegrass, acoustic and electric country, and rock, creating a quandary. CMH has always been among the best in getting its product into the stores, but many large chains wouldn’t stock Eddie & Martha’s LPs because they thought they were bluegrass, fans of their newer music couldn’t find it because it was in bluegrass browser bins, and for the same reason, buyers often bought albums thinking they were bluegrass when they weren’t. An unintended audition for David Allan Coe, who chanced to hear them at Nashville’s Station Inn, landed them important jobs in Coe’s group, where Eddie played a lot of electric lead guitar, and he and Martha were often the principal backup singers. During Coe’s three-hour shows, as much as an hour might be devoted to bluegrass, which Eddie points out, Coe “likes and respects 100%.” This was valuable exposure for bluegrass because, as Eddie says, more people might hear bluegrass at one David Allen Coe show than at a typical entire summer’s worth of bluegrass festivals.

The Adcocks very much enjoyed their stay with Coe, but the old restless creative urges set in again. In Eddie’s words, “See what we’re doing? We paid all the dues, opened all the doors, we made megabucks for a year and two months, and we feel we’d have no trouble walking in and getting a record out (on a major label) tomorrow, and I’ve got the bluegrass bug… again! I’m leaving a living to go back into a non-living.” In a business where sooner or later almost all performers whose livelihood is derived solely from being a performer must at some point at least face the temptation to reduce their art to a commodity, Eddie Adcock has consistently been willing to back his creative motivation with financial sacrifice. He is aware that his commitment along these lines has not always been accepted at face value, but he thinks, and feels strongly, that this time, his artistic motivation will be so apparent that it will, at last, be accepted as such.

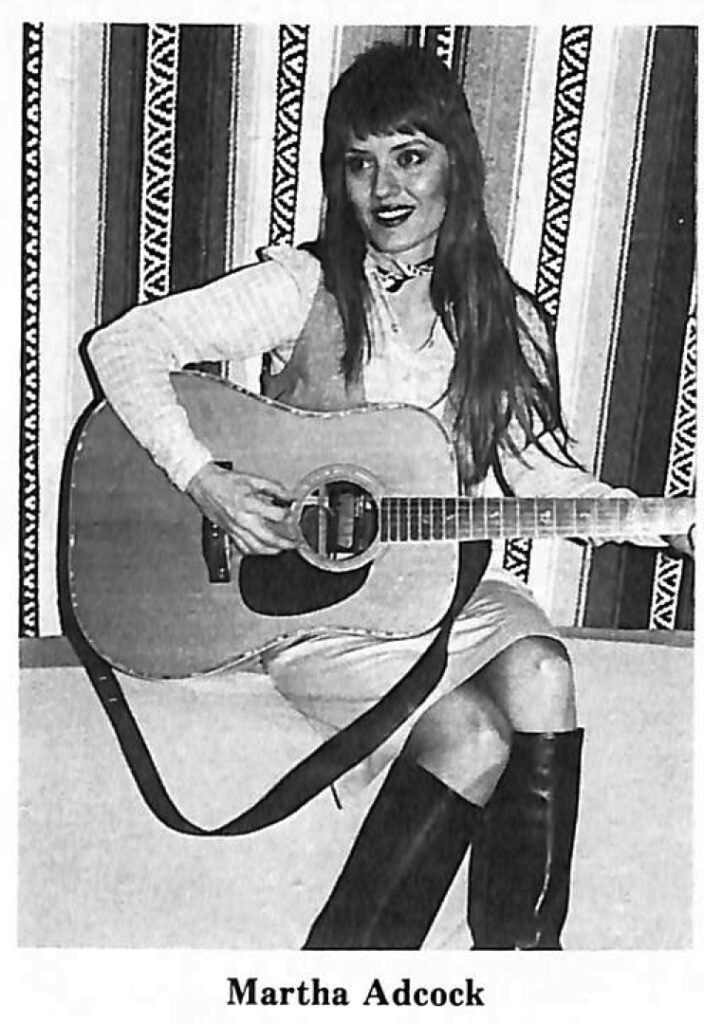

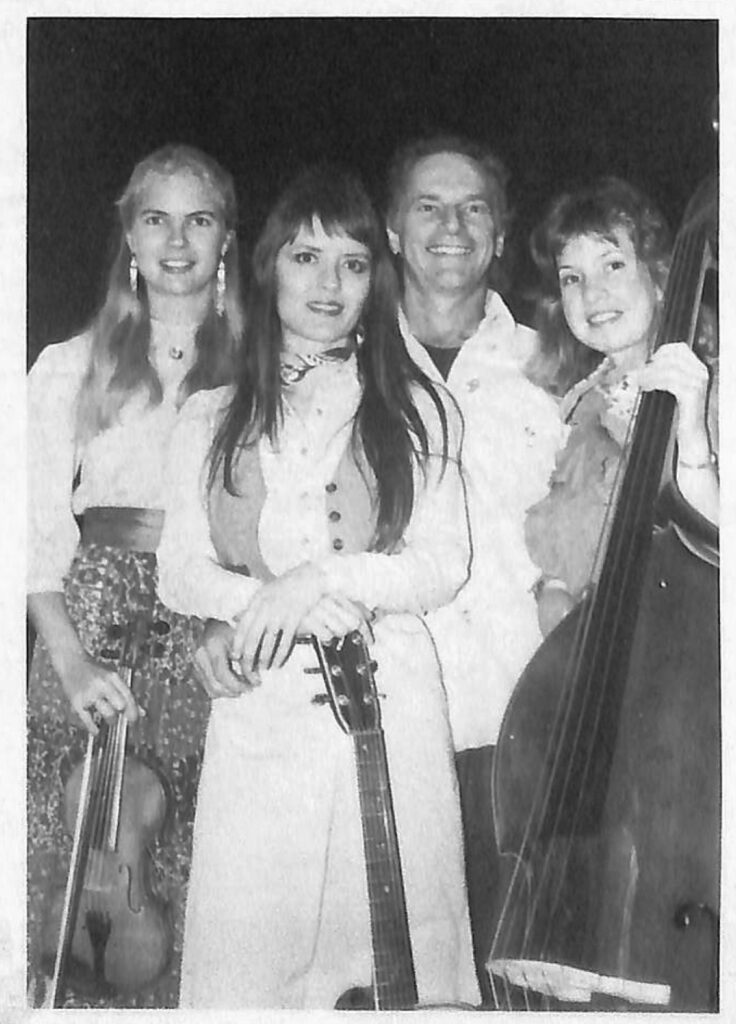

The performer’s hubris is often a volatile brew, so it is ideally fortunate that, as his personal and musical anchor, Eddie can draw on the musical sensitivity and personal strength of Martha Hearon Adcock. Martha was brought up in a respected family in Bishopville, South Carolina, where her father still keeps a large farm. Both her grandfathers played old-time fiddle, and both her parents were musicians, which is how they met. There was music in Martha’s childhood home, but it was of the practiced and polished sort, and her family was initially lukewarm to folk and country music. There was piano from around age five, and later a baritone ukulele and a tenor guitar. By age 16, Martha felt her hands were large enough to handle a six-string guitar, so there was a classical, and then a steel-string guitar. Her route to bluegrass took her through the early-1960s folk scene (Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, Chad Mitchell Trio, Peter, Paul & Mary, etc.); she seems surprised that she was not aware of the Country Gentlemen, often heard on the folk circuit in those days, although she was aware of Flatt & Scruggs, and the “hair-raising banjo of Ralph Stanley.” She attended Coker College in Hartsville, South Carolina “very early,” although with characteristic common sense, she wonders if she shouldn’t have gone into the “real world” instead. Later, she attended art school in Sarasota, Florida, and for awhile was a news editor for a TV station and newspaper in Florence, South Carolina. By the time Martha moved to Nashville in 1973, she had been performing extensively as a solo for many church and civic organizations and at folk festivals, and as a duo with Irv Lewis of Johnsonville, South Carolina and as part of a trio called “Martha and the Walton Brothers.” She had begun writing songs, several of which have already been recorded in several musical contexts with Eddie. These and others of hers are an important part of Talk Of The Town’s repertoire, as well as other songs that she had been “saving back” specifically for the new group. By the time she moved to Nashville, Martha had been going to major festivals and conventions (Galax, Union Grove, Camp Springs, etc.), and had also learned to do musical instrument repair and inlay work. This, in turn, led to a job at Nashille’s Ole Time Picking Parlor, where lots of celebrities came by to jam, and where, within ten days, Eddie Adcock entered her life. Their romance was immediate, and Eddie taught her to run he sound system for the IInd Generation. By this time, Wendy Thatcher’s health was not the best, so Martha entered the band as a kind of supporting rhythm guitarist and vocalist at a time when she was just learning bluegrass rhythm guitar. By the spring of 1974, Wendy had left the group, and Martha has “been there ever since.” She and Eddie were married quietly in a judge’s chambers in York, South Carolina in 1976, and their life together is obviously one of positive compromise, not negative attrition. Martha’s musical appreciation embraces bluegrass, country, folk, jazz, rock and reggae music, so she brings a diversely-cultivated musical personality to Talk Of The Town. Displaying a total lack of egotism regarding her impressive litany of unobtrusive accomplishments, Martha notes, “I was always encouraged to do as much as I can, and made to believe I could do a lot. There was a lot of pressure to be a professional person, along prescribed lines, and make it easy on myself. But I was encouraged to be what I wanted to be, and I was never one to take the easy way.” All of which brings a knowing smile of understanding to the face of Eddie Adcock.

Talk Of The Town’s bass player is Missy Raines, the West Virginia native whose musical depth and breadth of experience belies her youth. Her playing combines extensive influences from several kinds of music with a technical mastery of her instrument, and a tone unusually robust and melodious for an acoustic bass. Missy comes from an enthusiastic bluegrass-loving family, who would often take her to as many as thirteen festivals a summer. All through high school, she routinely spent as much as four days on the road with different bands (one included Diana (Mrs. Ben) Eldridge) out of Keyser and Short Gap, West Virginia. Eventually she joined the Washington D.C.-area band, Stars & Bars, and later worked briefly with Cherokee Rose. Although she always loved traditional bluegrass, she found herself searching for newer sounds, and was impressed and strongly influenced by Boone Creek, the IInd Generation, and the records of the early Country Gentlemen. Although she was playing guitar by age eleven, Missy’s main instrument has long been the bass. She numbers among her bluegrass influence George Shuffler, Roger Bush, and especially the work of Tom Gray. She also has particularly high praise for John Palmer—one of the great masters of the triple slap.” In the mid-1970s, she heard her first non-bluegrass bass playing, from jazz bassist Dave Holland, in the 1975 untitled all-star LP on the HDS label. Shortly thereafter, her attraction to Dawg music brought her to the work of Rob Wasserman and Todd Phillips. A principal influence has been the respected jazz bassist Ron Carter, whose above-the cloud-cover consummate artistry allows his “choices,” in Missy’s words to be “so simple,” yet so completely right. Missy’s last affiliation prior to joining Talk Of The Town was with Cloud Valley, the group that, after several years together, disbanded after spending much of 1985 touring most of America in the Harry Chapin musical, “Cotton Patch Gospel.” Missy found Cloud Valley a rewarding experience, but remembers the difficulties of a new and original band establishing itself. When four highly talented, eminently decent young musicians essentially undamaged by life set out to create music that is different and innovative, there is bound to be a certain amount of grumbling, simply because the rear guard always makes it a point never to understand the vanguard. Cloud Valley ultimately found a respectable, devoted following. Their music, being new music, did not fit many preconceived musical notions; perhaps more importantly, it did not aggressively or directly refute them, either. Thus, those who failed to relate to Cloud Valley’s fine music often didn’t know why they failed to understand it, which, in turn, created a new dimension of oblique frustration. Like an artist who is not fully appreciated in his or her own lifetime, the ironic legacy of Cloud Valley may well be the number and importance of the usually clearheaded observers who misunderstood them.

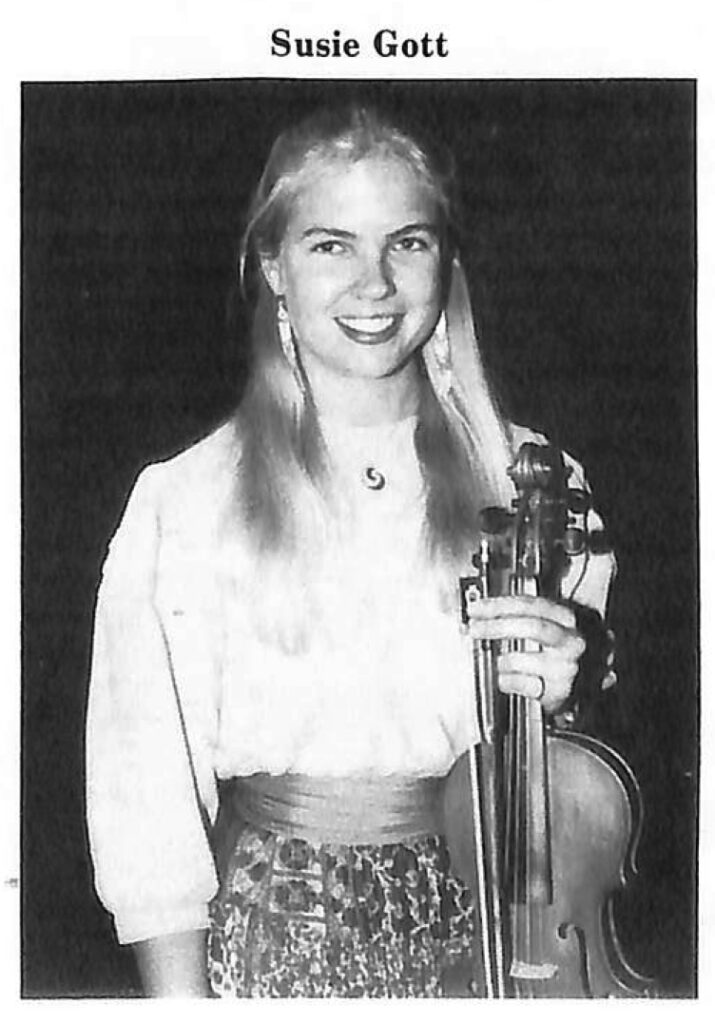

“Primarily what I have to offer is a strong arm, an open mind, and a sharp ear,” says Talk Of The Town’s fiddler, Susie Gott. Susie comes from a family whose commitment to its music is so strong that it governs not only where it lives, but how it lives. Susie’s parents, Peter & Polly Gott, both attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York where Peter’s interest in the banjo became so strong that he dropped out in his fourth year, in order to concentrate on playing music. Not only did Peter and Polly move to North Carolina to more fully experience the music and its cultural surroundings, but they chose to live a self-sufficient lifestyle, the way the people who originally formulated old-time southern mountain music lived. They built a log cabin, and grew all the family’s food. This meant that in an era when some people need to pump a little wattage just to brush their teeth, Susie grew up with neither electricity nor running water. The location chosen for the family was in Madison County, in western North Carolina, an area not only rich in musicians, but a favorite source area for collectors from Cecil Sharp to John Cohen. Peter immersed himself in the music in several ways: collecting, getting people who had let their music lapse interested in singing and playing again, instrument repair, and of course singing and playing himself. Susie remembers the family home as being a frequent stopping-off place for musicians such as the New Lost City Ramblers, and she remembers her father playing in a bluegrass band when she was as young as two years old. Susie started playing fiddle when she was twelve, about the same time her brother Tim, two years younger, was learning music himself. For awhile, Susie, Tim and Peter worked as a trio, and then got together with ex-Blue Grass Boy Ralph Lewis’ sons Don and Marty as the Gott-Lewis Offspring String Band; their approximately one year together included performances at local clubs and one at the Smithsonian Institute. By this time, Susie’s mother Polly had begun to play bass, so father, mother, son and daughter played as a family band (see “Cowbell Hollow String Band,” Skyline SR-002 November 1981), combining bluegrass and old-time music, often featuring both styles of banjo in the same tune. After Susie graduated from college with a degree in environmental studies, the band toured Europe for eleven weeks during the summer of 1983, playing mostly folk clubs in England, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Austria and Holland. During the last two years, she has taught string band music, and played old-time, bluegrass, Irish, and folk-rock around Asheville, North Carolina. During the summer of 1985, Susie also played in the reconstituted Southern Connection after three of its four members left to join Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver. It is obvious that, in playing so many different styles, Susie has been influenced by a wide variety of great musicians, from the noted old-time fiddler Franklin George to the great Tommy Jackson, whose records to this day can still point the way for any aspiring fiddler. But, beyond specific influences, Susie is literally playing her heritage. Her singing voice achieved its full strength naturally, in the rural, unconfined atmosphere in which she grew up. And because she has heard so much great music in its natural habitat, her own music pours forth with an appealing honesty and candor that brings a strong, special dimension to Talk Of The Town.

Any band that elects to record a Randall Hylton song automatically establishes itself, thereby, in the forefront of good taste; Randall’s “Have I Loved You Too Late” will be in Talk Of The Town’s already-recorded first album. From contemporary Nashville, where the hardiest of songs can still sprout through the “production” pavement, come “Hillbilly Girl With The Blues,” “Wild And Blue” and “He’s Taking It Hard.” “Hard” And “soft” country rock, respectively, provide “Midnight Rider” and “Breeze.” There is vintage Hank Williams in “You Win Again,” and earliest Elvis echoing in “Baby, Let’s Play House,” both with their strong blues undertones brought to the forefront, and, among others, a favorite from the days of the IInd Generation, “Dog,” co-written by Martha Adcock. Taken together, these songs offer a strong sampling of the group’s proficiency and versatility, virtues that abound in Talk Of The Town stage shows. Among the almost fifty songs and tunes the listener is liable to hear in a single evening’s sets are banjo tunes, including “Dear Old Dixie,” “Foggy Mountain Breakdown (with a “Foggy Mountain Chimes” ending), Eddie’s new original “Champagne Breakdown,” and the well-remembered medley, “Newsreel;” guitar showcases that include “Sugarfoot Rag,” “Guitar Echoes” and “Matchbox Blues;” and fiddle’ tunes from “Fire On The Mountain” to “Crazy Creek” to Susie’s own “Lament For A Lost Lover.” But Talk Of The Town is also most definitely a band that sings. All four members sing with great power and wide range, offering a full spectrum of key choices, tonal possibilities, and trio combinations. Eddie finds himself singing everything from bass in quartets to high-range lead, and choosing which two girls will fill out a trio with him is always a choice between and best. “Give This Message To Your Heart,” for example, is a song that has always separated the persons from the non-persons, and there are dozens more, all scintillating with eloquent precision. “Gold Watch And Chain” and “My Favorite Memory,” recorded previously by Eddie & Martha, are back. “She Used To Love Me A Lot” was one Eddie and Martha used to do with Coe, and “Please Come To Boston” was a mid-1970s pop hit for a singer who is now one of Nashville’s hottest writers. There are generous helpings of 1950s country—“Crying My Heart Over You,” “Loose Talk” and “Love And Wealth,” and distinguished earlier country classics like “Remember Me.” Eddie’s high regard for the late Don Reno is evident in the group’s treatment of “I’m Using My Bible For A Road Map,” and “I Know You’re Married,” as well as several of Don’s best instrumental tunes. Often, to conclude a set that has featured not only great, seamless vocal combinations and sparkling instrumental prowess, but Eddie’s unique arrangement ideas—a Scottish interlude in “Sugarfoot Rag,” a latin beat in “Loose Talk,” or his Travis style, single-string and Reno style picking all in one banjo break —Talk Of The Town will do “Up Around The Bend,” the rousing 1970 pop hit that was in the IInd Generation’s first LP, giving its audience in the process a grand tour of their refreshing, dynamic approach to not only several styles of country music, but many of its musically compatible neighbors, as well.

It is very clear that this band is not a leader and his underlings, but a partnership. It has not been planned as a one-man, three-girl band, and that’s not the way they hope their music comes across. Missy, for one, says, “I really try very hard to have a non-gender attitude about my music, because that’s the way I want my music taken. I think the environment in this band is going to allow it to grow, like no other musical experience I’ve had. I used to hear, ‘You’re real good for a woman;’ I don’t hear that so much [now]—that’s a compliment to me, but also indicative of the way things are turning.” She notes that in earlier eras of country music, when women sang, it was often from the man’s point of view; she cites Martha Trachtenberg as a present-day writer who writes from a woman’s viewpoint. Ask Talk Of The Town how much of its material will be from a woman’s perspective, and Eddie chimes in immediately and enthusiastically, “Three parts!”

Talk Of The Town is by design an acoustic band, so much so that its audiences will not be seeing Eddie’s beloved invention, the gitbo. “Although the gitbo is a superior instrument in every way,” he says, “it won’t work in Talk Of The Town, because people will see the electric cord and get the wrong idea.” This, in spite of the fact that “The gitbo is an acoustic banjo, it is not an electric banjo—there is no magnetic pickup in that banjo at all. I use the same kind of pickup that Barcus Berry uses—it’s just my own design, that’s all. [It has] proved itself to me; I knew I could do it, I built it —it’s on seven bluegrass albums, and no one knows which ones they are. The banjo Eddie will be using onstage with Talk Of The Town was built by Harry Lane; Eddie says unequivocally, “The Lane Banjo is the best acoustic banjo that I have ever played in my life.”

Musical growth is what Talk Of The Town is about, but it is a particular kind of musical growth. Much commercial music that is primarily a commodity eagerly grafts onto itself anything that is working elsewhere. By contrast, Talk Of The Town concerns itself with what might be termed organic growth— creatively exploring, with “harmony and drive,” the full potential implicit in their music itself. For his latest challenge, Eddie says, “I don’t have a thing in this world to worry about—I don’t have to have a home, I don’t have to have a car, I don’t have to have any money—I don’t have to have anything but the love of God and I can go.” Asked if financial reward might be desirable, Eddie says, “It’s time I thought about a little money, so I’m thinking about a little money this time—but I’m not thinking about it to the point of changing my music to adapt to it.” He can look back thirty years to the resistance to his musical ideas he initially encountered, but “the Gentlemen used them, and they sold the group.” And he knows that musical classifications are often subject to flexibility “I was accused of wanting to play anything but bluegrass; now, that is bluegrass!” He is proud of both what he has done—“I’ve gone thirty years of working with nothing but the best musicians in the business, and I haven’t changed,” and what he intends to do —“Thirty years of good musicians at least ought to tell people [they ought] to come out and see if these girls can really cut it, and they can!

I think what we’re doing is fresh in both an old and new way—I think a lot of people in bluegrass have forgotten harmony and drive; [we’ll be] coming back in and concentrating on some of the old things that may be new to a lot of people now.” To which Martha adds, “For this day and time, we will not be as progressive as the IInd Generation.” For Eddie, “There’s a river of notes going by at all times; I’m a fisherman—I just throw the hook in. The secret is not to dislike [any form of] music whatsoever—I love everything, and I listen to everything. I love Van Halen; I love Bill Monroe.”

The “want-tos” that have stayed with Eddie Adcock throughout his career have also become the hallmark of this entire great new band. Missy Raines sums it up this way: “We all just want to play the music we have strong roots in—all anybody who’s worth their salt in any kind of music has ever done, is play their own thing. They got that way from their roots, and whatever they did through the stages of their musical life. The cycle must always go on.” And, in the talented and capable hands, minds and hearts of Eddie Adcock, Martha Adcock, Missy Raines and Susie Gott,—Talk Of The Town —the cycle is about to shift into overdrive again.