Home > Articles > The Tradition > Dwight Whitley

Dwight Whitley

Harboring The Legacy

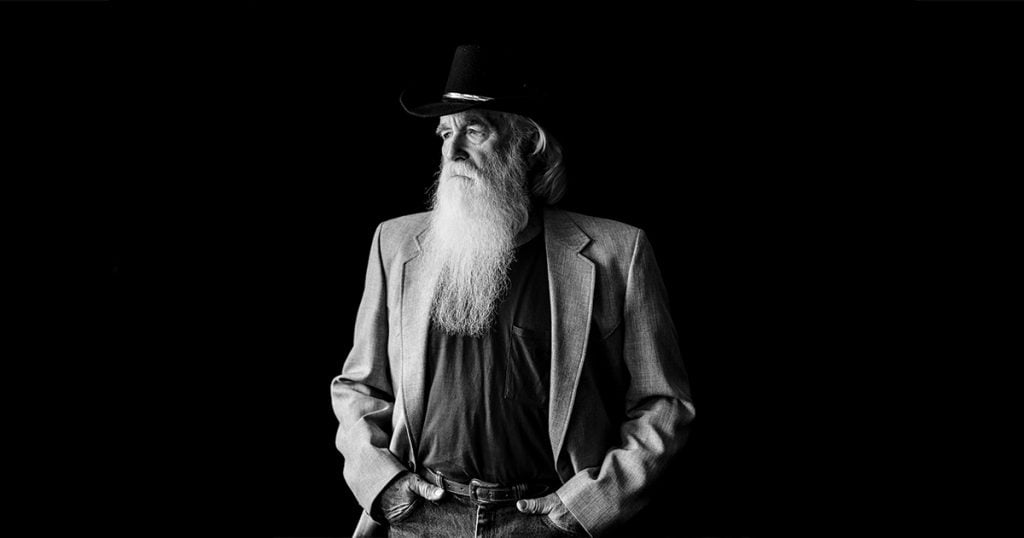

Photo by Megan Sweeting

Briar Fork was in many ways your typical holler in eastern Kentucky, a rural road off State Route 32, four miles from Sandy Hook, near the Little Sandy River. Elliott County has some of the prettiest scenery in the state. It’s not exactly in the bluegrass region that lies to the west, not quite in the Appalachian foothills to the south, but an equal blending of Kentucky’s rolling hills and farmland that all to come together as if to say “Here’s where you’d stop to watch the sunset, or where you would awake extra early, just to see it rise.”

However, Briar Fork was exceptional in another way. This was the home of Lewis Edmon Ferguson, a blacksmith by trade, and one of the greatest musicians in an area that was known for fine musicians. Lewis was born in 1884, and by the time he was in his early twenties, he along with his fiddle-playing comrade Addie Hutchinson were a vital source of entertainment for Elliott and the surrounding counties. This would prove to be a breeding ground for some of the most important bluegrass and country music of the twentieth century, and in large part, it would derive from “Grandpa Ferguson,” as he was called by the Whitley boys who would soon inherit the gift of music from their banjo-playing grandfather.

Dwight Whitley was born in Briar Fork on July 24th, 1946. He was the first-born son to Elmer and Faye Ferguson Whitley. The Whitleys lived within eyesight to the Fergusons, and Dwight recalls as a child “I’d spend more time at Grandpa Ferguson’s house than my own.” During this time, young Dwight took notice to the music of his grandpa. Grandpa Ferguson made Dwight a homemade banjo from a coffee can, but with a hand-carved neck that was very playable. It didn’t take long before Dwight was developing the “overhanded” banjo style of his mentor. When Dwight was eight years old, his father Elmer bought him an open-back Kay banjo for $35, a hefty sum for an electrician in 1954. This store-bought banjo found its way into the Whitley home around the same time as their youngest child, Keith, was welcomed into the family.

On Christmas Eve of 1957 the Whitley family lost their home to a house fire and their next permanent residence would be in the town of Sandy Hook. It was here that young Keith’s interest in music would blossom. He took to it as soon as he was big enough to physically participate. By the time he could talk, he was singing the country songs from mother Faye’s 78 rpm record collection. Faye was also a guitar player and before Keith’s little arms could reach around her Stella guitar, she was showing him the chords. The Whitley boys were soon making a variety of music from country, gospel, to rock & roll. While Dwight was in high school, he played in rock bands—first “The Ramblers” 1962-64, then in “The Marauders” in 1964, eventually including the pre-teen Keith into the band with Dwight proclaiming “he was the best singer that we knew of.”

Around 1962 Dwight met the love of his life. He had just turned 16 and had a 1950 Ford. Dwight recalls running around town and seeing Flora Ison, “Flo.” Upon doing a double take, he found out who she was, where she lived, and then “proceeded to visit her until I convinced her to marry me!” laughs Dwight (They just celebrated their 57th wedding anniversary.) Another musical connection evolved at this instance; Flo’s father, Milo, was a devoted music lover who had (at that time) a state-of-the-art reel-to-reel tape recorder. Local bands would come to Milo’s home to practice or have informal jam sessions so Milo could record them. Milo also had a banjo, so I must wonder if this re-piqued rocker Dwight’s interest in the instrument during the young couple’s courtship?

Shortly after Dwight and Flo were married in 1965, he took a construction job in Middletown, Ohio where he would work through the week and return home to Sandy Hook on the weekends. Dwight recalls, “I would listen to Paul “Moon” Mullins’ bluegrass radio show in Ohio, and I just loved the Stanley Brothers. I went into a music store and bought one of their records, then brought it home to try it out on Keith—he loved it! He learned every song on the album, and this continued every couple of weeks. I’d bring down another Stanley Brothers record, and Keith would absorb it in its entirety. We had already been playing some, but not good quality music until we learned the Stanley Brothers.” Unbeknownst to them then, this was a monumental moment in time, facilitated by Dwight, that would go on to mold and shape so much bluegrass music from that point onward.

Most bluegrass fans associate Keith’s introduction to our music through Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, but in fact the first live bluegrass band that he witnessed was J.D. Crowe and the Kentucky Mountain Boys in the winter of 1966 in nearby Morgan County. Dwight tells the story; “I had a hot-rod police cruiser at the time, and it had come a snow, but the slick roads didn’t bother either one of us, so we went to see them play. There were only a handful of people there due to the weather, but the band played like there were 5,000 in attendance. We went back to meet the band after they’d finished. I remember Doyle Lawson was on guitar then and on the way back home, Keith told me that he was ready to start a bluegrass band. I agreed.” A plan was in place.

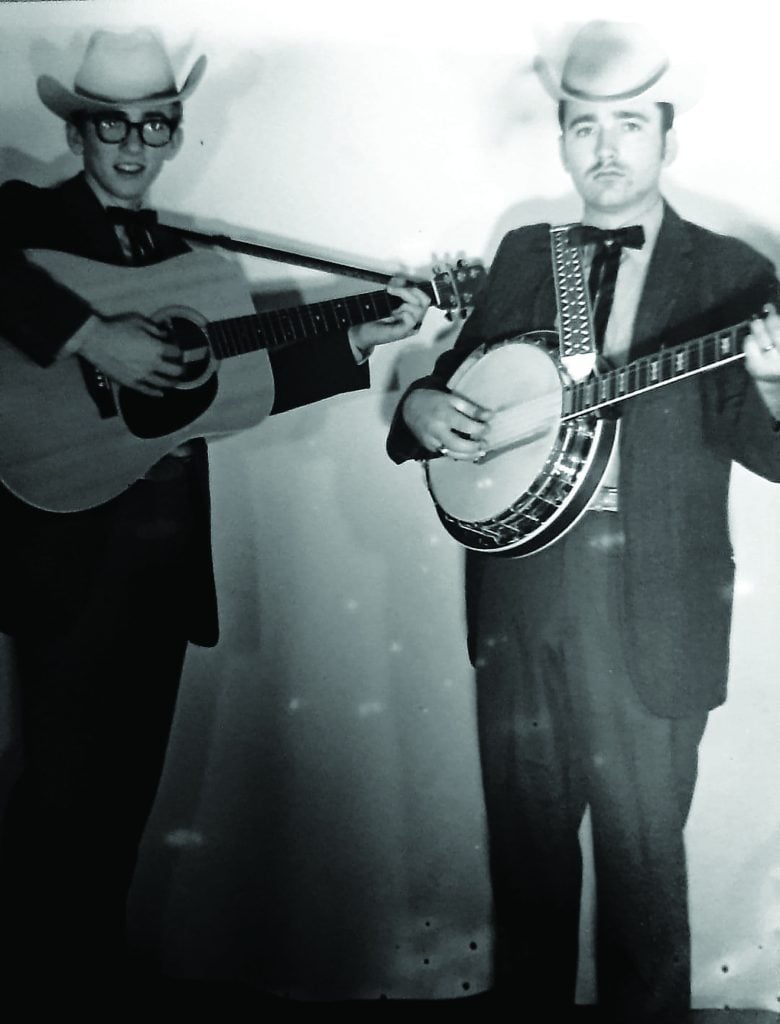

The new band members were all local to the Whitley’s home base; A. M. DeBusk on fiddle from Ezel, Woody Whitt on mandolin from Sandy Hook, Marvin Adkins from Wrigley played bass, Bob Spurlock from Campton added rhythm guitar, Dwight on banjo, and Keith on guitar and vocals. Keith named the band the “East Kentucky Mountain Boys,” inspired by J.D.’s band name at the time, but soon Dwight suggested a change to the “Sourwood Mountain Boys” with A. M. playing the fiddle tune of the same name as their theme song. This lasted for a while, but they eventually settled on the “Lonesome Mountain Boys.” By this time their instruments improved with Dwight getting a brand-new Gibson RB-250 banjo, Keith with his first Martin guitar, a 000-28, and Woody Whitt with a shiny new Gibson F-12 mandolin. The boys were slicked up and eager to be heard.

In 1967, Rockdale Jamboree was a well-established country music park in the Ashland/Cannonsburg, KY area where country music stars, as well as local bands throughout the area, would perform. It didn’t take long for the Whitleys to show up for an audition. Ken Alfrey was the talent scout who would give them a listen. Dwight recalls “About mid-way through the second song he said, “Stop! No need to go further, you boys can play here anytime you want!” This momentum led to the band contacting local radio stations and a radio spot on WGOH in Grayson, Kentucky. While there, they were approached by Carl Johnson who ran the local Montgomery Ward store. Carl wanted to sponsor them for a TV show on WSAZ in Huntington, West Virginia. Dwight said, “Keith wrote a jingle for the show that would rival the Martha White theme.” Unfortunately, the TV and radio performances were all done live and there are no known recordings of these segments.

From there, the demand for live performances increased and the need for free weekends resulted in a new “pre-recorded” radio show that ran on WLKS in West Liberty, Kentucky. Their father, Elmer, recorded two shows a week from the garage of their home. One was a straight-ahead bluegrass show to air on Saturdays, and the other was an all gospel show to air on Sundays. These shows were sponsored by Ralph Brewers’ Western Auto store in Sandy Hook and the Mountain Rural Telephone company, which had its headquarters in West Liberty. Now they were working nearly every weekend, as well as being played on the local radio.

The band also took part in a second TV show on WKYH-TV down in Hazard, Kentucky. It was sponsored by Chic Brewers Chevrolet in Campton and was largely due to guitar player, Bob Spurlock, who was a salesman for the dealership. Spurlock would handle the emcee work and plug the business during the show. Although they were not paid, the band traveled in a brand-new car provided by the dealership, and after the tapings they all got a free steak and lobster dinner from the best restaurant in town. Keith would ride with Dwight from Sandy Hook to Campton, there they would all meet up at Brewers Chevrolet and take Route 15 south, down through Jackson, then deeper into the mountains of Hazard. Unaware to them at the time, they would be passing near the home of a young Roy Lee Centers who, in just a few short years, would arise as one of the premier bluegrass musicians alongside Ralph Stanley. Soon thereafter, a teenage Keith Whitley would travel the country with Roy Lee as a fellow Clinch Mountain Boy in undoubtedly one of the most important bands in bluegrass music history.

In 1969 Keith met up with another teenage bluegrass musician, Ricky Skaggs, and the two instantly hit it off. Keith invited Skaggs to guest on some of the radio shows and live performances. Dwight would play shows with Keith, Ricky, and Ricky’s father, Hobert. Keith and Ricky also played in other band configurations during this time. Something was obviously brewing and during the summer of 1970, Ralph Stanley would hear the two singing Stanley Brothers songs in Ft. Gay, West Virginia. Ralph would invite the boys to come sing and play on his shows whenever they could. One of these performances was back on the grounds of the Rockdale Jamboree, where Bill Monroe’s first Kentucky Bluegrass Festival was being held in September of 1970. By 1971 the boys were off and running as official Clinch Mountain Boys with a brand-new record, Tribute to the Stanley Brothers ( Jalyn JLP-129).Dwight recalls that Keith came back home after the recording session in Dayton, Ohio, concerned that Dwight would be hurt at him for using Roy Lee Centers on the banjo instead of him. Dwight was in full support.

Dwight and Flo were already starting a family with their first son, John Dwight, born on June 21st, 1968. Their second child, Michael Keith was born on January 30th, 1972 at Saint Claire Hospital in Morehead, Kentucky. Dwight Whitley is a hard-working family man who has always provided for his family. Through the years he’s held several jobs, including being a certified welder, a pipefitter, a union carpenter, and quality control inspector for the mines, truck, rail, and river facilities. He has also worked as an over-the-road truck driver, hauling jet fuel for 20 plus years. Although Dwight would spend a lot of time working away from home, he and Flo would settle in Elliott County to raise their boys in the same place they themselves were raised; a fine place to watch the sunset.

Although Dwight wasn’t pursuing a career in music, he kept playing and it was always the banjo that called to him when the mood would hit. In 1972 he was in a band based out of Ashland, Kentucky, the Big Sandy Express which included Robert McGuire on guitar, John McGuire on bass, Terry McDavid on mandolin, Ron Eldridge on fiddle, with Dwight on banjo. This was a fine band. Dwight recalls, “We once went to Richmond, Kentucky and they were having a band contest. Our band came in second place, I’m thinking Ron got first or second on the fiddle, and I took first in prize in the banjo department, so we did well that night. We made a little money.”

Fiddler Ron Eldridge speaks on working with Dwight. “All I can say on describing Dwight Whitley can be summed up in one word—solid. He is about as good as they come, and Keith was the same. The whole family was that way.” Ron goes on to talk about a memory of he and Dwight playing a show with Hylo Brown up in Pennsylvania, saying, “Dwight could have played with anybody at that time.”

It didn’t take long until Flo and Dwight’s son John was playing music too, and his talent was evident early on. During Keith’s return visits to Sandy Hook, they would always play together. Keith often said that “John had the best hard-driving style rhythm that he’d ever heard.” Another Sandy Hook native, expert banjo-playing attorney Johnny Lewis grew up as a classmate to John Whitley. Lewis tells of learning to play banjo at the Whitley house, where Dwight taught him his first rolls. Eventually the boys had a band of their own, the True Grass Band, as named by Dwight. Johnny also states that “John had the best rhythm that a banjo player could ever ask for.” Their youngest son Michael would also pick up guitar and start to sing in the following years.

As Keith’s career progressed, Dwight and family would support him from the sidelines, attending all the shows that were in the area, and Dwight fondly remembers taking full advantage of Keith’s time as a member of J.D. Crowe & The New South. “Not everybody knows this, but Keith was a pretty good banjo player, and I would have him pick up licks from J.D. that I’d be struggling with. Keith would memorize the parts and come back to show me how he did it.” Johnny Lewis recalled, “Even after Keith moved to Nashville and was doing country music, when he’d come back home, all he wanted to do was play bluegrass, and it would always happen at Flo and Dwight’s house.”

As the eighties went on, Keith’s country music career progressed first as a writer/demo singer then a full-blown, chart-topping radio star, but he never left his roots, or his ties to Eastern Kentucky. He would often perform in his home area and one of his last concerts came near a place where so much of it seemed to have started. The Rockdale Jamboree was just a few miles from the scene of the March 1989 show in Boyd County. This would be the last time Dwight would see his little brother. Dwight goes on to say, “The last time I saw him face-to-face was at the Summit High School concert that he did on March 17th, 1989. He had two buses then, and he was traveling on the new one, and he wanted Flo, me, and the boys to come on the bus after the show and we did, and there were all kinds of people trying to get to him, and I said, ‘Keith I’m going to go on home, and I’ll see you another time.’ He said, ‘Ahh, stay. I want to talk to you.’ I said, ‘Well, you’ve got these fans out there,’ (And he did not shy away from his fans. He gave them all he had time-wise) so we came on home and that was the last time I saw him. Earlier that night, he said, ‘Why don’t you come out on the road with me? You don’t have to do anything but just be with me. If you want to play and sing with me, we’ll do that, if not that’s okay too.’ I said, ‘Keith, I’ve got these boys I’ve got to raise, get them through school, after that, maybe.’ But I’ve often wondered if it would’ve been different. He was lonely.”

Tragedies have been all too common to the Whitley’s. With brother Randy passing in 1983 in a motorcycle accident, now brother Keith gone, Dwight was determined to honor their legacies with a fitting tribute, The Keith Whitley Memorial Bike Ride, which started in 1990 and still runs to this day. The Whitley boys were all avid Harley Davidson enthusiasts; the ride starts in Sandy Hook, passing by Randy’s grave in the Elliott County Memory Gardens, then winds up at the Springhill Cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee, the final resting place of Keith. Also, in 1990, Flo took over the Keith Whitley Fan Club. She has worked endlessly to promote and keep Keith’s memory alive. Her tireless work has been a source of inspiration to other artists who seek to gain knowledge about Keith and Dwight and their upbringing in Sandy Hook. She also works as the editor of the Elliott County News, Sandy Hook’s newspaper publication.

The Nashville music scene was still feeling the shock five years after Keith’s passing with its version of a tribute recording, Keith Whitley; A tribute Album (BNA 1994), with a star-studded cast of artists, but it was not the first. In 1993, Dwight recorded a record of mostly unreleased demos of Keith’s but the tribute album wasn’t released until 1995, Dwight Whitley Brotherly Love (Neon). It’s a solid country album. The single “The Legend and the Man” gained international attention and produced a video that featured the role of Keith being played by Dwight’s son John. The North American Country Music Association International nominated “The Legend and the Man” as video of the year, and it won. Dwight recalls that he was a little on the fence with the country music venture; he said “I really wanted to do bluegrass.”

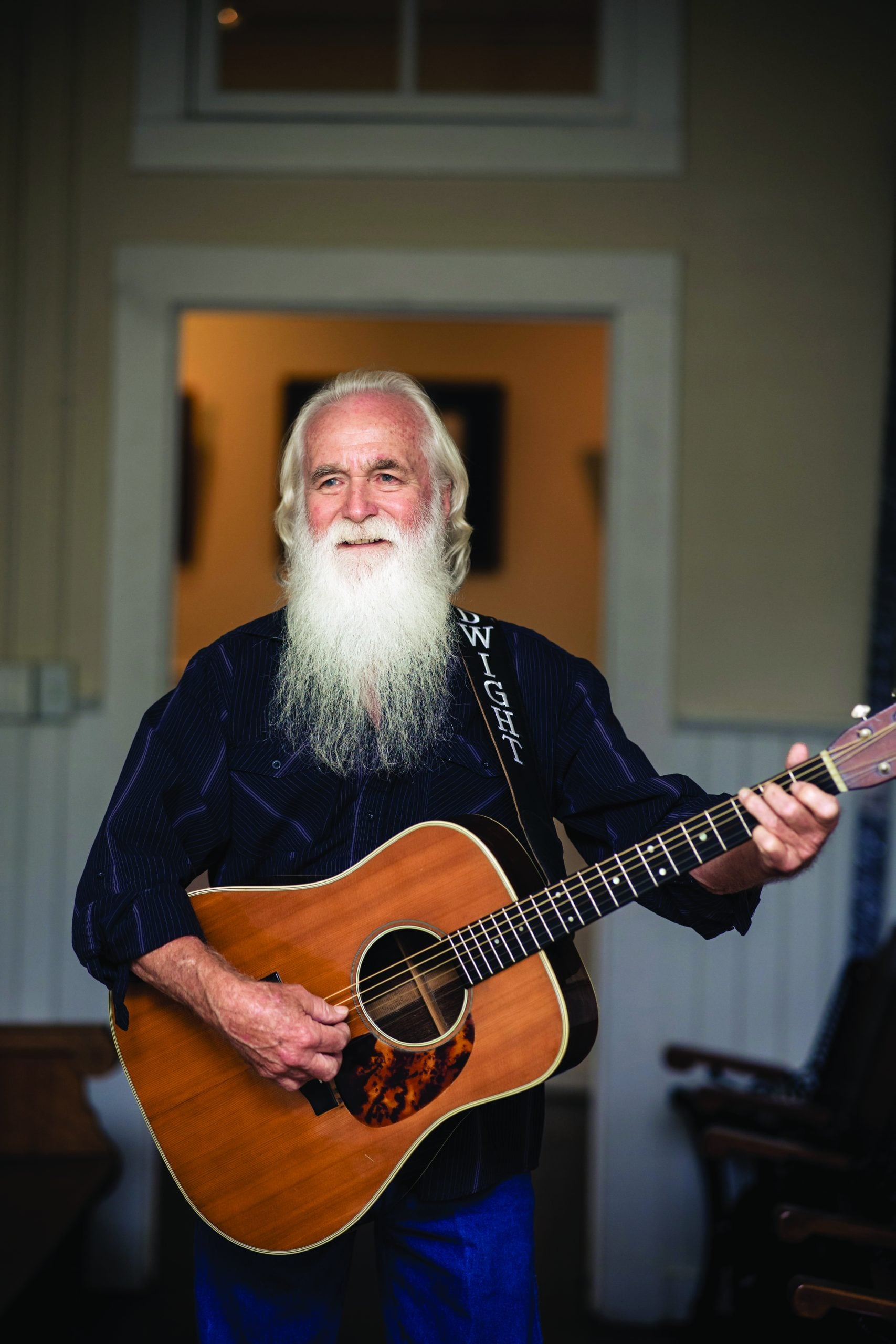

As the years went on, Dwight remained active with music as well as the Memorial Bike Ride, but then on March 30th, 2002, his first-born son John was taken in an auto accident. Dwight recalls “That just devastated me and Flo. I didn’t play music for ten years, I didn’t pick up my banjo, guitar, ride my bike or nothing. I just dropped it. I just kind of turned into a hermit, then one day I got a call from a friend that I used to play bluegrass with, (my mother was in the nursing home at that time), and he asked why don’t we go play for your mother? So, we did, and then I started playing again.” Dwight’s spirit lifted as he said, “Now I’m playing all the time, I’ve got banjoitis! I’m back up to nine of them [laughs.] I’m getting all these guitars back; I think it’s a sign because people are giving them to me. I recently acquired two of Keith’s old guitars, and then Blueridge presented a Carter Stanley memorial guitar in honor of Keith at the Ralph Stanley Hills of Home Bluegrass Festival.” Such a fitting gesture after learning that it was Dwight who was feeding those Stanley Brothers records to his kid brother all those years ago. Thank you, Dwight!

Dwight has weathered the storms in his life, but hard times are still there for the Whitley’s with the recent loss of their youngest son, Michael Keith on December 16th, 2019, and then Dwight’s sister Mary on April 10th, 2021. But with the hard times comes some solace through music. The recent announcement of Keith Whitley’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame this fall brings cheers and a rally of support for Keith and the family. Dwight has graciously taken part in the tributes that have arisen as a result of that nomination, with Flo always by his side, supporting and documenting every step of the way.

In my own personal gratitude of the news, I’m realizing that this Hall of Fame induction is a dream come true for a lot of people, for bluegrass and for country music. I imagine a kid out there who’s just discovering it, his fingers hurting from learning that first chord on a cheap guitar. Perhaps a big brother is there introducing him to new music—maybe its “Somewhere Between” by J.D. Crowe, maybe it’s “Oh Death” from Ralph Stanleys’ Clinch Mountain Gospel. He hears Keith Whitley—it changes his life. I hope Dwight knows how much he is appreciated and how important it is that he continues to represent the Whitley legacy, how much it’s needed. As he concluded in our last conversation, “I’ve got all these instruments now. I’ve got to play them.”