Home > Articles > The Archives > Dr. Ralph Stanley: Generations of Influence

Dr. Ralph Stanley: Generations of Influence

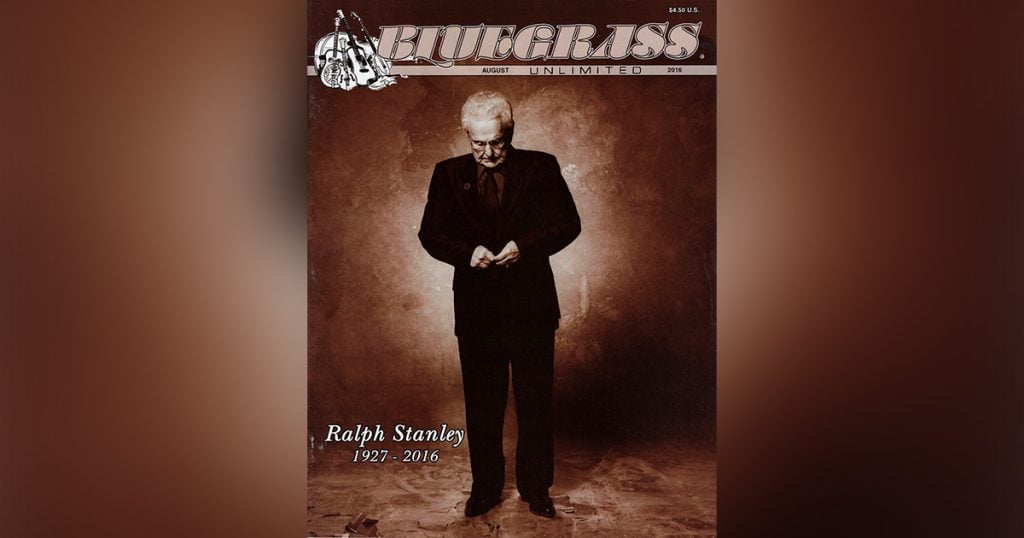

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 2016, Volume 51, Number 2

Just one day before Dr. Ralph Stanley passed on June 23, 2016, musician Lucy Cochran posted the now-famous video of Stanley singing “Pretty Polly” with Patty Loveless and the Clinch Mountain Boys on Facebook. Cochran is an excellent fiddler whom I first saw play on a very late night at the Appalachian String Band Festival, an annual get-together in the mountains of West Virginia, otherwise known as “Clifftop.” After graduating from the prestigious Berklee College of Music, she found herself in a heavy-metal country band called Stump Tail Dolly. The loud, experimental and fun group is not something that the late Dr. Ralph would have listened to, yet his influence is there. Said Cochran when she posted the “Pretty Polly” video: “If I spent the rest of my life doing nothing but watching and rewatching this perfect moment in time, I would be ecstatic.”

Less than 24 hours later. Dr. Ralph was gone. Cochran responded to the sad news. “I posted that video last night, obviously before Ralph passed, because it is so perfect and powerful that it moved me to tears,” said Cochran. “When I was 9, my dad took me to see the Down From The Mountain tour. Sometime during the concert, Ralph came out to sing one of his many perfect a cappella numbers. He looked tiny on the massive stage, singing to several thousand people. He must’ve looked lonesome out there—surely the song he was singing sounded that way— because out of nowhere Patty Loveless showed up on stage next to him and held his hand while he finished his song. I remember being moved to tears in that moment. Since then, I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen him and heard him and cried with him. Ralph Stanley is one of the only artists that can make me shut up and listen long enough to really hear what he had to say. Of course, I’m crying now. But I’m happy knowing that he’s probably somewhere with Carter now, making the most beautiful music that ever was.”

Barely one year into my writing career, I found myself backstage at the Cincinnati show on that very same Down From The Mountain tour in 2002. Several months earlier, a concert by Dr. Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys was the first official concert that I ever covered with a press pass. I wrote an article on the show for Gritz Magazine and brought Dr. Ralph a copy of it while backstage. “Well then,” said Stanley. “Let’s see what you wrote.” Suddenly, I found myself standing there in front of a living legend who was reading my article about him, and I am freaking out, hoping he would approve. And, he did approve. And in the 14 years since then, I was lucky enough to have interviewed him several times.

The Down From The Mountain tour was based on the soundtrack of the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which sold almost eight million copies and gave American roots music a boost, and also helped to rejuvenate Stanley’s career. In 2002, I interviewed the Ohio-based bluegrass and gospel great Lillie Mae Whitaker of the group Lillie Mae & the Dixie Gospelaires. She talked about the growing roots music movement that inspired a new generation of kid musicians, like Lucy Cochran.

“I’m seeing a lot of young people in the audience that act like we just started bluegrass,” the late Lillie Mae said “It amazed me back in 2001 that the ones that came to a festival in Michigan acted like this was all brand new. Ralph Stanley was on the bill with us and I said, ‘Where have they been all of our life, Ralph?’ He said, ‘I don’t know. Everywhere I go, it’s that way. They act like this is something new.’”

Dr. Ralph was known for his clawhammer-style of banjo playing, something he learned from his mother while growing up in the beautiful Clinch Mountains of Virginia. Later on, he would also develop a rather unique way of playing Earl Scruggs’ three-finger-style of picking the banjo when he and his brother Carter helped to solidify the brand new genre of music called bluegrass in the 1940s and 1950s. As Dr. Ralph got older and his hands hurt him more and more, he brought others in to play the banjo for him. One of the best of the Clinch Mountain Boys to play the Stanley-style of three- finger banjo picking was Steve Sparkman.

“In 1994, when I joined him, Ralph had a farming accident and broke his hip,” said Sparkman. “Ralph II went to him and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ He said, ‘Well, we need to try and get Steve if we can get him.’ So, Ralph II contacted me and told me about it and said they needed some help for at least six weeks while Ralph healed from his surgery. I grew up going to a lot of the festivals and Ralph would always recognize me. He remembered me because I learned to play his style, and he knew that. I think he was kind of flattered by it, with a man learning his style, which was very distinctive. Most banjo players, they pattern after Earl Scruggs or J.D. Crowe or somebody like that. Ralph was always kind of out in a field of his own. It’s a mountain style of picking that expresses feeling, and it expresses the melody one hundred percent. No real hot licks or nothing like that. It’s just full of feeling, and people can feel it when you play it, and they love that.”

These days, Kentucky born and bred Sammy Adkins records and travels with his band, the Sandy Hook Mountain Boys. Back in the day, however, he spent several years touring with his idol Dr. Ralph. When the young Adkins began to ride the roads of America as a Clinch Mountain Boy, he found himself hanging out with other greats of the bluegrass genre.

“When I played for Ralph, we’d travel together with Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin, and Jim & Jesse and a bunch of them,” said Adkins. “Jimmy, Ralph, and I were trying to schedule a coon hunting trip. I coon hunt all the time. I still do and, in fact, I went last night. I have a bunch of coonhounds, and I love to fool with them here at the farm. Jimmy was a big coon hunter and Ralph liked to hunt, but we never did go. Ralph and I took our dogs on the road a few times, but we never did get together with Jimmy. I love horses, too. I’ve had horses all of my life. Ralph had a bunch of horses as well. We used to trade about every weekend on something; horses or something else. I used to go up there and ride them for him. Ralph and my dad also traded horses. They would come down here and my mom would fix a big supper for them and they loved that. Ralph and I and the boys had a good time, playing and singing. I don’t regret one second of it.

“I learned a lot of the ropes of being on the road from Ralph,” said Adkins. “He was always about being on time. You can’t wait until an hour or so before show time because you might run into a wreck or breakdown or something like that. You’ve got to allow a lot of time to be on time. Just like Ralph said, ‘I’d rather be two or three hours early than be a minute late.’ That’s the way I am. I like to have plenty of time for show time, to allow time in case you need it in case something goes wrong. You never know when you’re traveling. He taught me a lot of stuff, things that I picked up from being around him and watching him and doing things for him.”

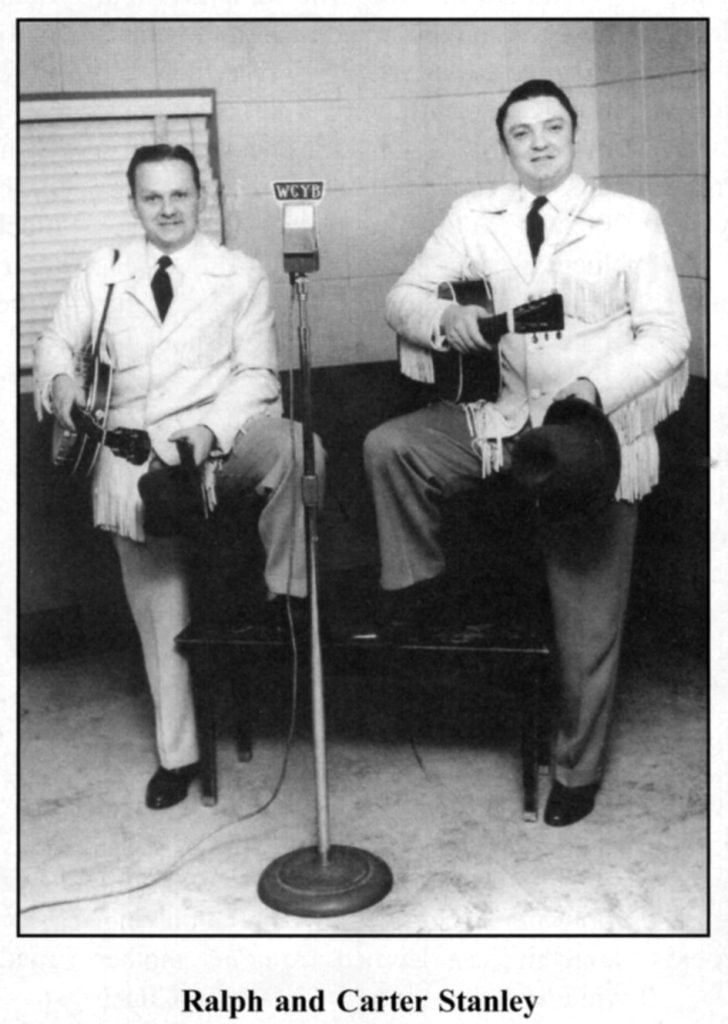

For many, the two decades that Dr. Ralph performed and recorded with his brother Carter are the truly magical years of his musical life. The Stanley Brothers only grow more mesmerizing as time goes by. Before Carter prematurely died in 1966 at 41 years of age, he was the leader and main songwriter and emcee of the amazing Stanley Brothers.

Melvin Goins, now an IBMA Hall Of Famer in his own right as a member of the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, was a member of the Stanley Brothers. Goins talked about Dr. Ralph’s sorely missed older brother. “We worked a lot of drive-in theaters in the summer time,” said Goins. “In the fall and wintertime, we went inside with schoolhouses and stuff like that, playing matinee shows for children. That was some of the first shows we played when I went to work with them in January of 1966. It was myself and Carter and Ralph and George Shuffler. There were four of us. Carter was a well- spoken man. When he talked to you, he was real easy to talk with. If he was talking about something he felt good about, he just laid it out and didn’t hold anything back. He was just straightforward. He was not laid-back. He was out with it—plain and simple, just a mountain man. He was a great guy. His singing and emcee work, he was great at that. He really knew how to handle people. He could go on a stage and he could make you laugh or he could make you cry. He had a tone in his voice with his talking and his singing and he could just about hypnotize a crowd of people.

“Carter was a good boss,” continues Goins. “He was a good trainer. One thing about him, if you followed his footsteps, you had your work cut out for you. You either did it his way or you didn’t, and he knew when it was right and when it was wrong. If it was wrong, he’d tell you about it. You had to stay on the tip of your toes to work with him because he was hard-driving. He played hard-driving music, and that’s the way he created it, and you either played it the way he played it or you didn’t stay. You just left. I mean, there wasn’t no playing around. I’ve seen him cut up and joke with you just as funny as anybody in the world, and then on some days he wouldn’t speak five words to you. That was just his turn, that was his way, and everybody knew it.”

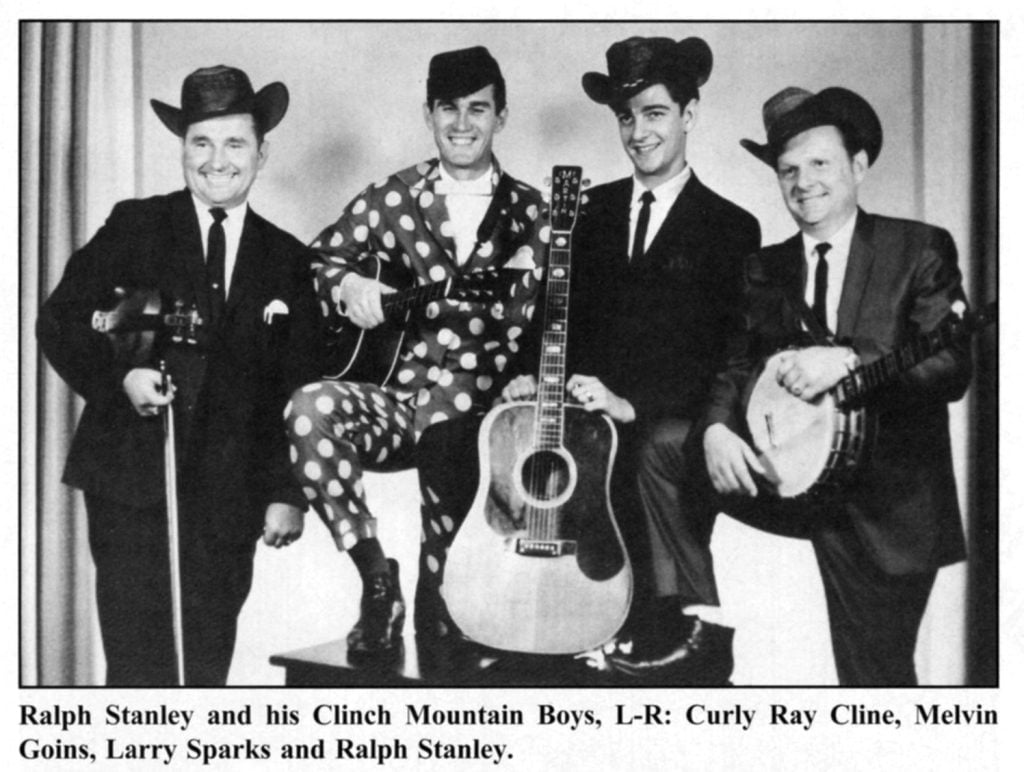

After Carter died, everyone connected with the Stanley Brothers were torn to the ground. Eventually, when Dr. Ralph decided to carry on, he chose a teenage kid to take the lead singing slot and that was future IBMA Hall Of Famer Larry Sparks. Sparks told me about one memorable moment in those rough post- Carter days. “I wore Carter’s boots, by the way,” said Sparks. “I wore his boots after he passed away. He wore a size ten, and I wore a nine-and-a-half, so I say I didn’t quite fill his boots. If you look on the Stanley Brothers Folk Concert album, one of the best albums they ever did in my opinion, you’ll see that there was brown boots with black toes on them. That’s the ones he had when he died. Ralph had them up under the front car seat, and he let me wear them and play his guitar for about a year. Carter was one of the finest—one of the best. He was a good entertainer, a good singer, and he and Ralph matched perfect together. So, I really treasure the little bit I worked with them and appreciated getting out there with them a little bit. But, then I went on to start my band in 1969 and tried to do something on my own.”

There were hard and lean times for the Stanley Brothers; times when they toured as a trio with just Carter, Dr. Ralph, and George Shuffler because they couldn’t afford to carry a full band. As a member of the Stanley Brothers, Shuffler would create a style of guitar playing called cross-picking. About a decade ago, I asked Shuffler about the creation of the cross-picking style while talking backstage at MerleFest.

“They say I started it. I don’t know,” said Shuffler. “I’d play one down and two up, jump it around, and put a solid roll on it. The reason why I did it is because they sung all of those slow, drawn-out songs that Carter and Ralph sang. I had to come up with something to fill in between the lines. Carter hated it until it started selling records, and then he was alright with it then. Carter was an interesting guy. He was always a friend to me.”

Jim Lauderdale, who recorded an amazing album with Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys called Lost In The Lonesome Pines, told me a story about the sense of humor of Shuffler and Dr. Ralph. “I was working on a record that became Lost In The Lonesome Pines. I was going to do some recording in California, and I flew George out there because Jack Cooke got sick,” Lauderdale recalled. “I wanted George to be on the album and when I brought him out to do that recording, we had several dates out there. I was opening up for Ralph solo, and then I’d sit in. We were out in Monterey, playing at a church where they would have these bluegrass shows. So, I was up there singing some real serious song and George and Ralph went around to the door where you walked into the church. I could see them from where I was playing up there in the pulpit area, and those guys were doing all of these wild gestures that just cracked me up. I could not keep a straight face. Those guys were hilarious. George had a really great sense of humor. They were trying to crack me up.”

In April 2014, George Shuffler died at 88 years of age. The day after Shuffler’s passing, Dr. Ralph wanted to share some thoughts on his long-time friend and bandmate. “I don’t have anything but the best to say about George,” Ralph said. “I miss him already, and he’ll be greatly missed by everybody. We played a lot of shows with just Carter and George and me. We had a good three-man show worked up. Sometimes, George wouldn’t go home for a month or two and if we had a day or two off, he would just go to our house and stay. We were real close. He’d let you know if he didn’t like you. He was straightforward. He didn’t try and hide anything. If he liked you, he liked you. If he didn’t, he didn’t. Sometimes he would take off a little while, but in a month or two, he would call and say, ‘Well, I’m ready to come back.’ Then, he’d come back and play several different times with us. And, we traded horses and rode horses and everything. If he told you something, you could depend on it. He was straight as a string. A lot of the old ones are leaving, and it’s sad. But, it’s coming to me, and it’s coming to you, and it’s coming to everybody.”

In honor of Shuffler, Dr. Ralph tried to keep a cross-pick guitar player in his band when possible. The best Clinch Mountain Boy to carry on that tradition was James Alan Shelton. Unfortunately, the bad news would keep on coming in 2014. In April, a couple of weeks after Shuffler was gone, Shelton got news that he had cancer. Only six weeks after getting the diagnosis, he died on June 3rd. He was only 53 years of age.

As these last two years played out. Dr. Ralph’s health got worse and worse. About a year and a half ago. I interviewed his son Ralph Stanley II, who was touring with his own band at the time. Ralph II decided to record one last album with his father, which became the wonderful recording Side By Side. In February of 2015, he talked about his ailing parent and mentor.

“With George Shuffler, we lost one of the greatest guitar players ever, if not the greatest,” said Ralph II. “He fit right in with them. It was just those three at times. I guess they couldn’t afford to hire anybody else. That always amazes me, about how they had those hard times, yet made the best records. You go back and listen to those records now, and how did that happen? They had to have decent days or they couldn’t have made it and Dad wouldn’t be here today. James Alan Shelton died right after George last year, so that was a horrible time for the Clinch Mountain Boy world. I still miss ole Jack Cooke, who’s been gone five years last December. I think about a lot of those old Clinch Mountain Boys like Curly Ray Cline. Every time we’re out here playing a show, there isn’t a mile that goes by that I don’t think of them at one point in time or another. When you travel with them for so long and you know them, you miss them. Even when you’re just about to go onstage, you think about them when you’re tuning up or rehearsing. That’s the way I am. I think about all of the old-timers that I’ve played with, and I think about it all of the time while riding down the road. I was showing my boy Ralph the IIIrd how Jack Cooke put aftershave on yesterday, just for an example. Jack had a funny way of doing it, and I’d laugh at him every time. He’d get me tickled. You build memories with these guys, and when they’re gone, you really miss them.”

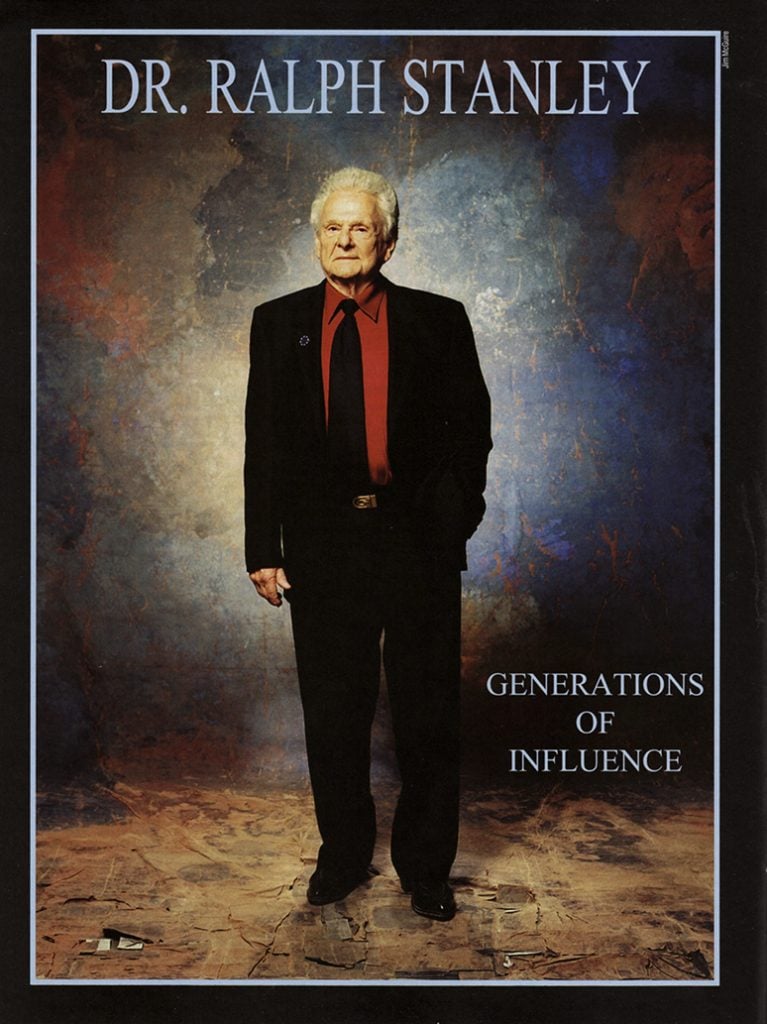

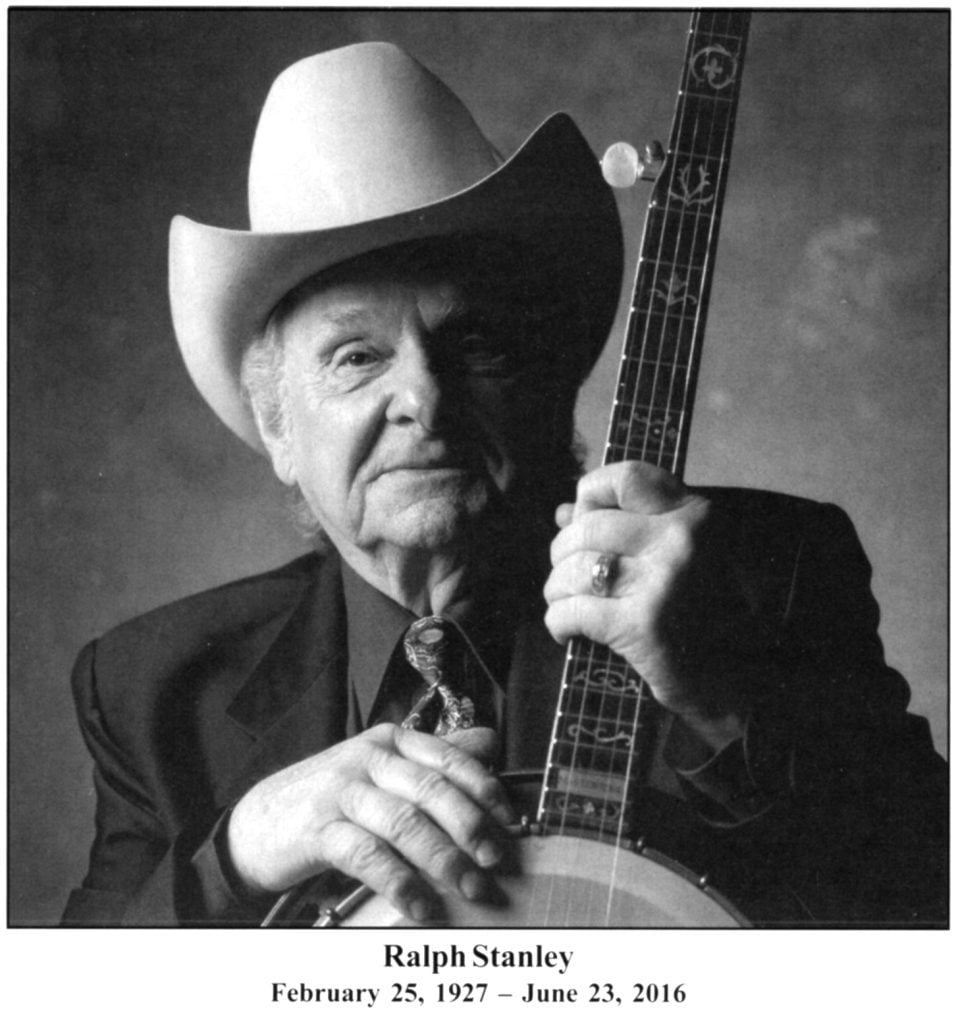

And now, Ralph Stanley is gone. A few years ago, in one of my longer interviews with the aging link to another time and era, Dr. Ralph summed up his own legacy this way. “I don’t know whether I play bluegrass or whether I play old-time country or folk or what,” he said. “But I know that mine is just old-time mountain music. I think tradition is real important, and I’ve always stuck with that kind of music. When people hear me, they don’t have to ask or look to see who I am. They know when I hit the first lick. They’ll tell you, they’ll know it’s Ralph Stanley. And I think that’s very important, and I think that’s the reason people respect me like they do. That’s why I’ve stayed around this long. Another reason, I guess, is that there’s not too much of the real, old traditional music anymore. It’s just music that gets in your soul. It’s got a feeling to it, and it’s true to life. And, it’s got all kinds of songs, you know—gospel, murder ballads, love ballads, and all of that. It’s good, simple music that you can’t resist.”

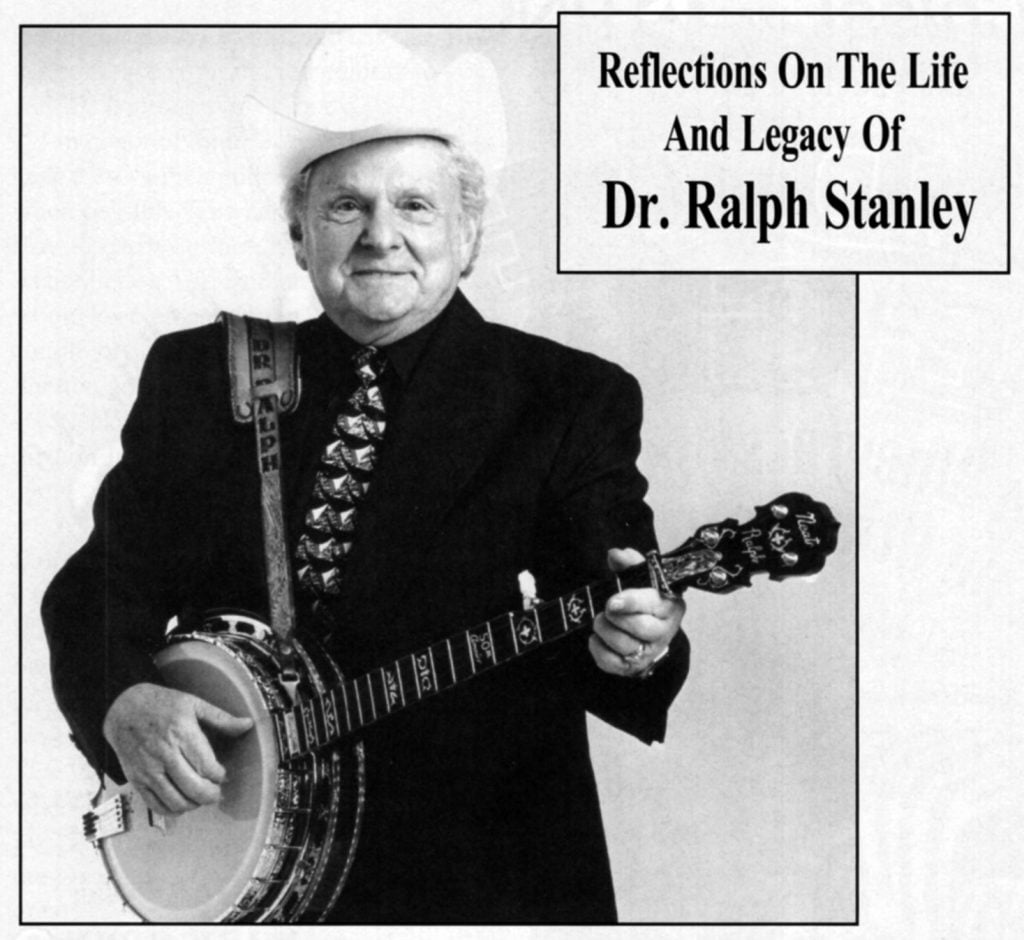

Reflections On The Life And Legacy Of Dr. Ralph Stanley

By Daniel Mullins

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 2016, Volume 51, Number 2

Well, Carter passed away when I was two years old. I never did get to see the Stanley Brothers, but I was raised on them. All my dad ever kept on the record player was the Stanley Brothers. Counting them up here in the stack, I think we’ve got about 51 of the Stanley Brothers records. I was born on the Stanley Brothers. They’re the ones who got me into bluegrass music. I tried to copy everything George Shuffler ever did on the guitar. I can remember sitting in there playing and scratching the records all up, and Dad getting on to me for picking it up and backing it up to hear [Shuffler’s] guitar breaks, trying to learn his guitar breaks. I tried to sing like Carter for years, and then I jumped up and did the tenor and tried to sing like Ralph on the tenor. That’s why my voice is about wore out now; I did that for many years at a lot of fiddlers’ conventions.

Me and my dad had a little group called Indian Creek back in the day. and we did a lot of Stanley Brothers stuff, and Larry Sparks and Dave Evans and, of course, the Johnson Mountain Boys when they came out. They were real hot. They loved the Stanley Brothers just as well, and they played a lot of Stanley Brothers songs. I loved them to death, too.

It breaks my heart to know that we lost a legend like Ralph. I only got to sing with him one time. That was a couple of years ago at Bluegrass On The Plains in Auburn, Ala. He was in the crowd at night, and they were carrying on and brought him up to sing one, and I got to introduce him. I was crying and carrying on and hugging, and I got to sing “Love Me Darlin’ Just Tonight,” me and Brandon Rickman. Brandon was singing tenor the first two choruses, and Ralph got off his stool and sang tenor on the last two choruses with me. That was the highlight of my whole career. I always wanted to sing with Ralph Stanley, and I got to do it.

—Junior Sisk

When I was a tiny little boy, I was about four-years-old the first time that I can really recall listening to this music and it moving me and having an impact on me that really reverberates today in my life. Oddly enough, it was not [Ralph’s] singing voice that first got me. That has tore me apart ever since, but when I was about four, my daddy went to the flea market and got me an old eight-track tape. Now I’m kind of dating myself a little bit, but he had an eight-track tape that he brought in, and it didn’t have a label on it at all. It was just a black tape, and my brother had an eight-track tape player in the house and I wasn’t supposed to bother it, so of course I did.

I popped that tape in there and the first thing I heard on there; it was a project called the Hills Of Home from 1967 that Ralph had done. One of the best ever. In my world, that’s one of the most influential recordings, maybe the most influential recording that Ralph made, and there were a lot of subsequent recordings that were great. Anyway, when it came on, I heard Ralph and Larry [Sparks] singing “Let Me Rest On A Peaceful Mountain” and the next thing that I hear is Ralph’s voice say: Carter, this is your song. That was your request, you’re at rest now in the hills you so often wrote about and loved so well… That voice was just so gentle and so—well. I’m about to get emotional thinking about it again. It was moving and, to a four-year-old boy, it was comforting. It had an effect on me where I got some sort of a calming effect on me as a child. Very quickly, I learned how to move it and get it back to that over and over and over.

To put it plainly, as the professional part of it, if Ralph Stanley hadn’t have done what he did, Don Rigsby wouldn’t be doing what he’s doing today. Anytime I open my mouth and sing, there’s the influence of all those intense years of studying music and his art because that’s the meat and potatoes of what I do. I do a lot of things. I sing different kinds of music, and I’ve since then broadened my horizons a lot, but if I hadn’t have gotten that foundation from the source, I wouldn’t have been able to. His voice and his power and his lonesomeness—I hope it’s evident in everything I do.

—Don Rigsby

Ralph was so identifiable, personally and professionally. There were so many characteristics that were a hundred percent Ralph Stanley. There was nobody else just like him. He was a mountaineer. We won’t see people cut from the same cloth as Ralph Stanley again. Thankfully, the good Lord allowed him seventy years to make music that He preserved. How cool is it that you can buy every note of music that Ralph Stanley ever recorded? That’s a body of work. He’s on a short list of American recording artists that every note of music that he played is still available in recorded format.

Ralph was consistent. Ralph showed up, he dressed professionally. Ralph and Carter Stanley, just like Bill Monroe, they hit the road in the 1940s with a purpose—to be professional and be successful. They looked the part. Not the hayseed image. I saw Ralph Stanley in a pair of jeans on his tour bus or walking around the camp ground, but those were very private moments. Ralph Stanley was in a suit and tie when he got to his performance. Ralph always was surrounded by good musicians. It didn’t matter how bad the sound system was, how small the festival was, how hot it was, how cold it was, how hard it was raining—Ralph Stanley looked and sounded the same on stage for seventy years.

As a banjo player, Ralph’s timing was absolutely impeccable. His roll was like driving nails. It was different—a different type of banjo and different style of banjo than Earl Scruggs. But his timing, him and Carter together, you didn’t have to think about where the downbeat was. It was where it as supposed to be all the time. I can’t play clawhammer banjo. I had Ralph show me two or three times. I started out three-finger-style, so it’s hard to adapt to a clawhammer-style banjo that Ralph was so good at. He was good at that until he died.

—Joe Mullins

He and Carter were a big part of my life. They meant a lot to me and, after Carter’s passing, Ralph could’ve had anybody he wanted to sing with him. He didn’t have to go too far, but he picked me for some reason. I guess he liked what I did, and I learned a lot with him too. He picked me to sing with him, and I was very, very honored.

I was 17 when I started with the Stanley Brothers, and I was close to 19 when Ralph brought me back. It was quite an honor. He thought I could sing his songs, so I didn’t argue with him. But he was good to work with, and what an experience. I’ll never forget it. I’ll never forget Ralph, and he’ll always be there in my heart and soul. His singing and his music, it’ll always be there. Sometimes that comes out of me—I can’t help it. Some of that stuff comes out. It’s just embedded in you—and natural, too, to sing like that. A lot of that Stanley sound will come out of me once and a while. Well, we’ve lost one of the last of the greats, and it’s very sad.

—Larry Sparks

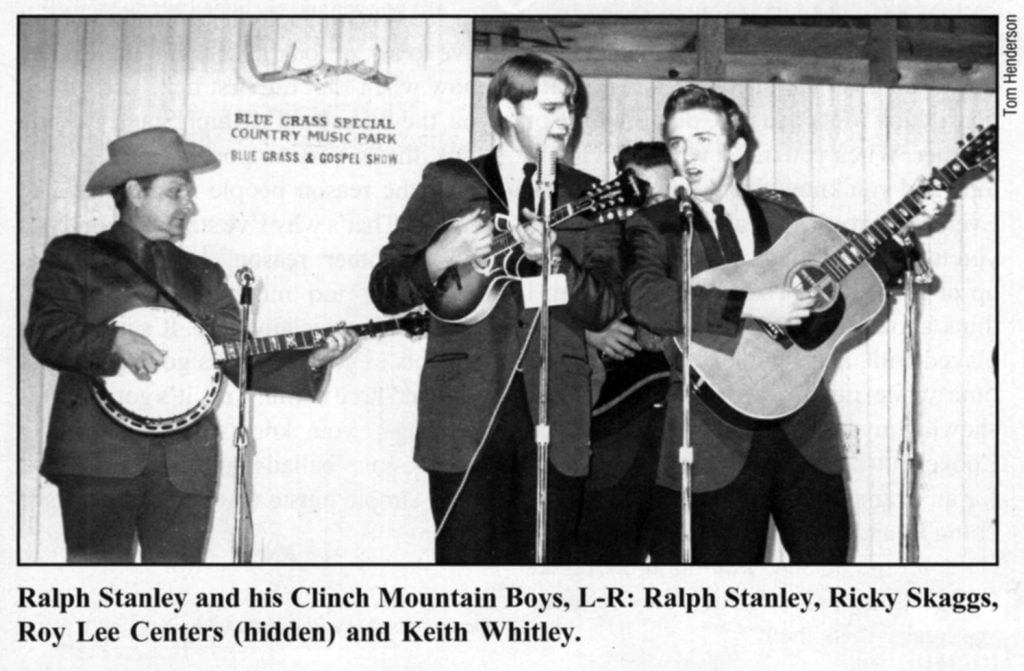

Me and Keith Whitley were 15 when we met Ralph in Fort Gay, W.Va. His bus had broke down and he had just hired Roy Lee Centers. I don’t know how long Roy Lee had been with him, but that was that transitional time between Larry Sparks and Roy Lee. So they came to this little old beer joint there in West Virginia across the river from Louisa, Ky. We wanted to see Roy Lee so bad because we had heard that he sung just like Carter, so we just couldn’t wait to hear that sounding duet again. The similarities, you know? So we talked our dad into taking us over there. Dad took us. It was Dad and Keith’s brother, Dwight—we all four went.

We got there, and we got our seats and was sitting there waiting for Ralph to get there and the show to start and the club owner came up to us and said, “Ralph’s bus has got a flat tire, and he’s gonna be about thirty-five or forty minutes late. Could you boys get up and sing?” How he knew we sung, I’ll never know. I’d never been to that place before. Me and Keith got up and sang the songs that we knew, which were Stanley Brothers songs. Keith and I had sung maybe three or four months together, just on weekends because he lived in Sandy Hook. Ky., which was in a neighboring county, and I lived there in Blaine area and went to school in Louisa at the high school there. So we knew a few songs, but everything we knew was Stanley Brothers songs.

Ralph come walking in finally and heard us play, heard us sing there, and instead of going to his dressing room, he pulled up a barstool and just sat there with his banjo in its case, just sitting there with his leather jacket on and his hat on. I was kind of embarrassed that we were on stage singing his songs in front of him. I could see him out of the comer of my eye, and I was just wishing that he would just go on back to his dressing room and that I wouldn’t have to watch him while I sang his tenor parts. It was like, “Oh my god, please get out of my vision. I don’t want to know that you’re even hearing me. I am so embarrassed.” But that night was a—you hear the expression a turning point or a new chapter or a defining moment and those kind of words in marking a new beginning. That truly was the beginning of a new chapter in my life.

—Ricky Skaggs