Home > Articles > The Archives > Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver

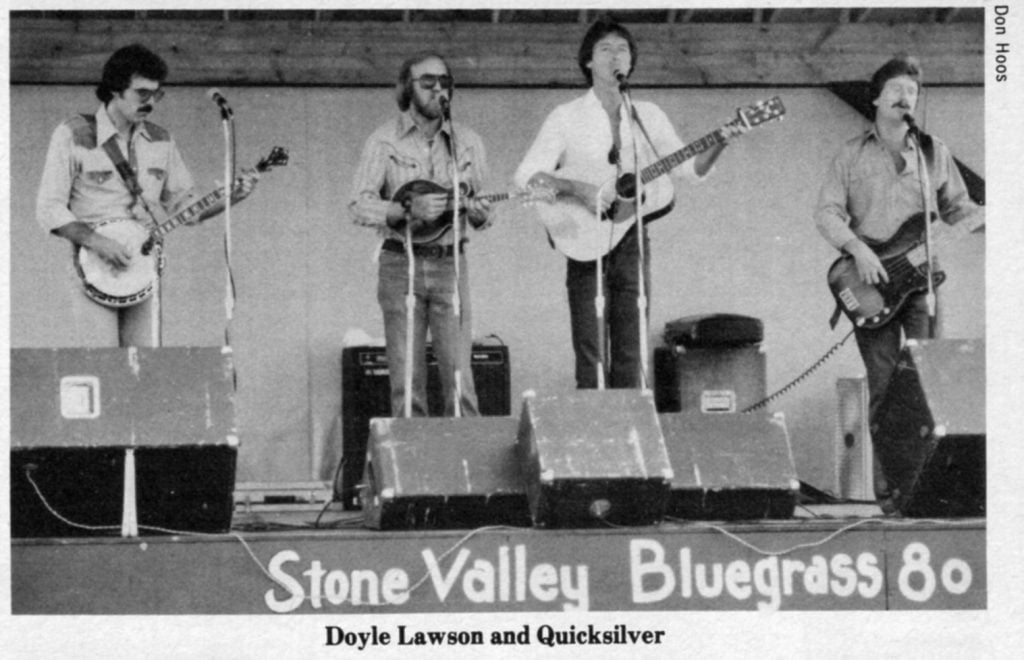

Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver

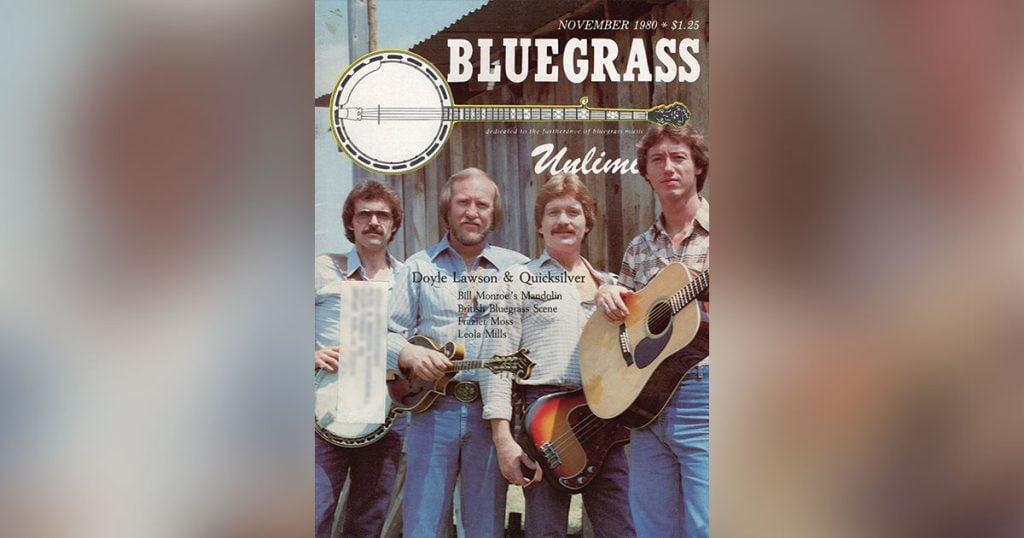

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1980, Volume 15, Number 5

“I’ve always been a pusher,” allows Doyle Lawson matter-of-factly. “If I’m doin’ good, I want to do better. I’ve never been as good as I want to be—as good as I can be. I hope I never get as good as I want to be.”

Doyle started pushing professionally in 1963 at the age of nineteen and has continued—with few interruptions—ever since. For many years he has been identified with dynamic, precise and tasteful mandolin work and with excellent tenor singing. During most of the 1970s the association was with the Washington-based Country Gentlemen. Since 1979 it has been with Quicksilver.

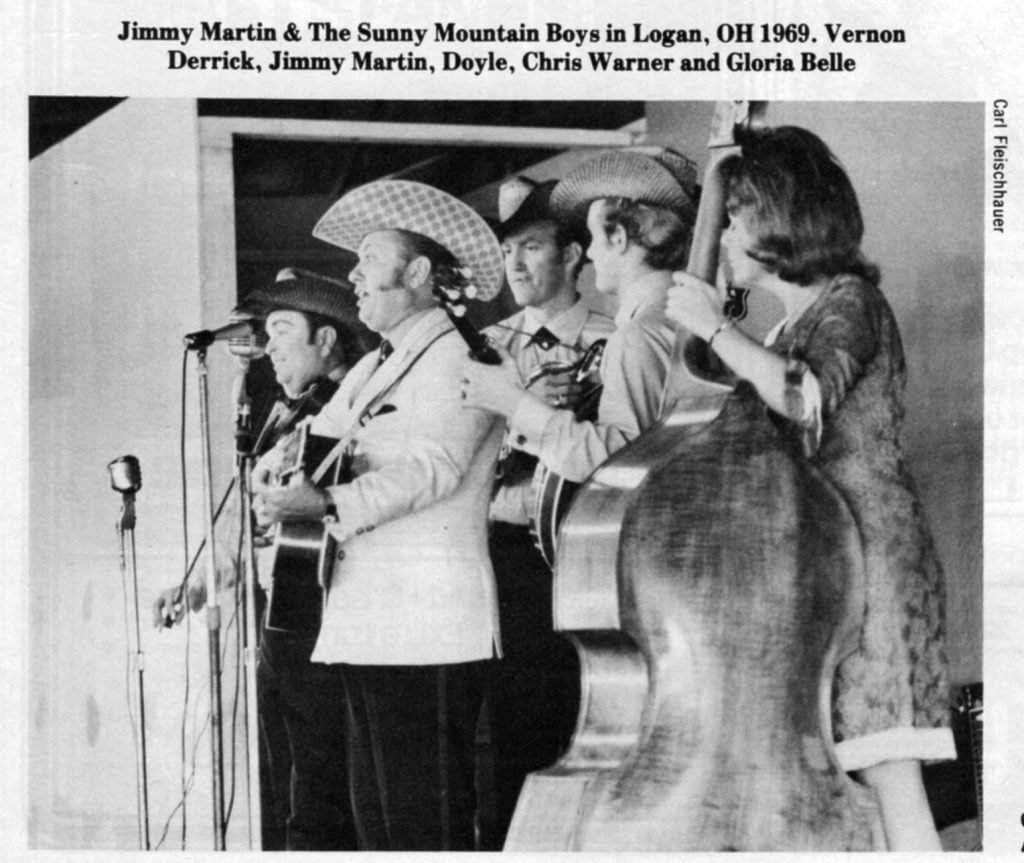

Doyle made his teenage debut, however, working out of his native east Tennessee. He was playing not mandolin, but banjo. His boss was mercurial bluegrass great, Jimmy Martin.

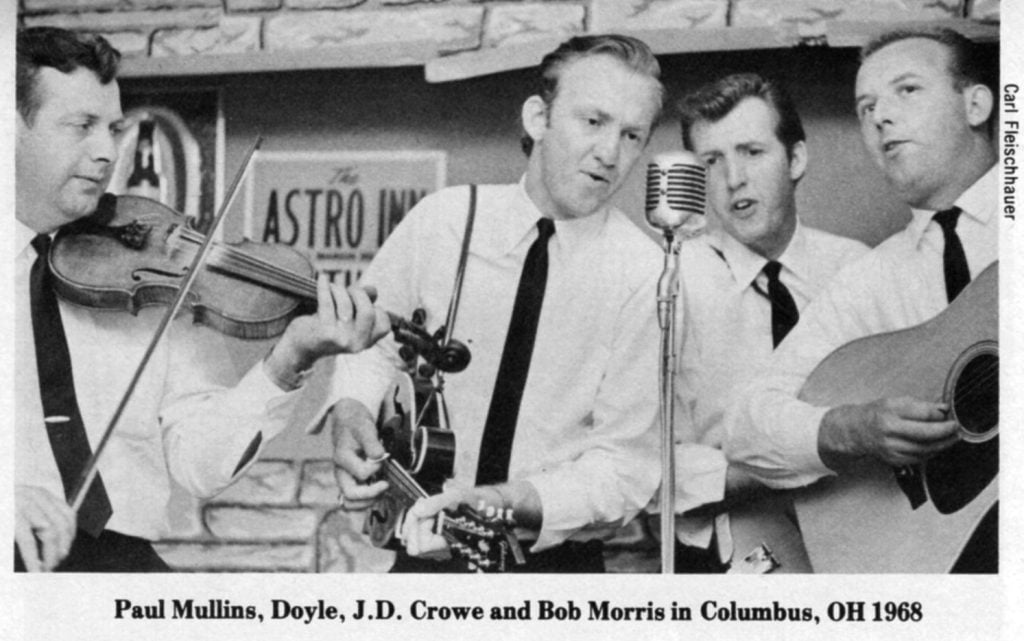

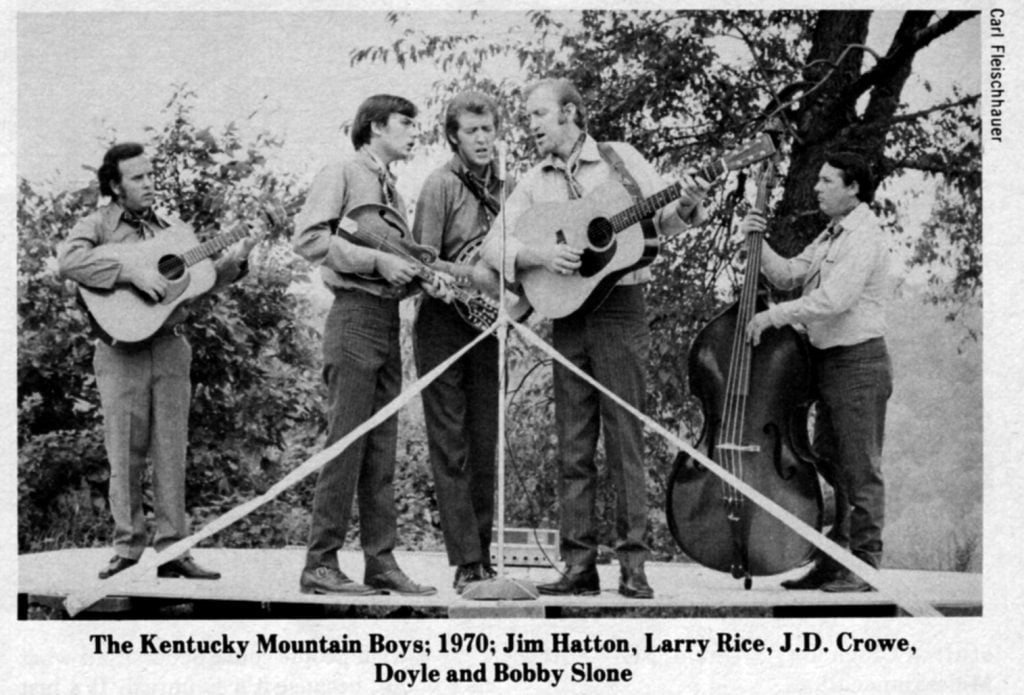

Following his initiation into show business and a subsequent period of disillusionment with music, Doyle surfaced again in 1966. This time he was playing guitar for another ex-Martin banjo player, J.D. Crowe.

At first it was just part time work in Lexington, Kentucky’s beer joints. By day, J.D. worked as a shipping clerk and Doyle became his assistant. Later, music became a full time occupation and Doyle was able to move over to his first love, the mandolin.

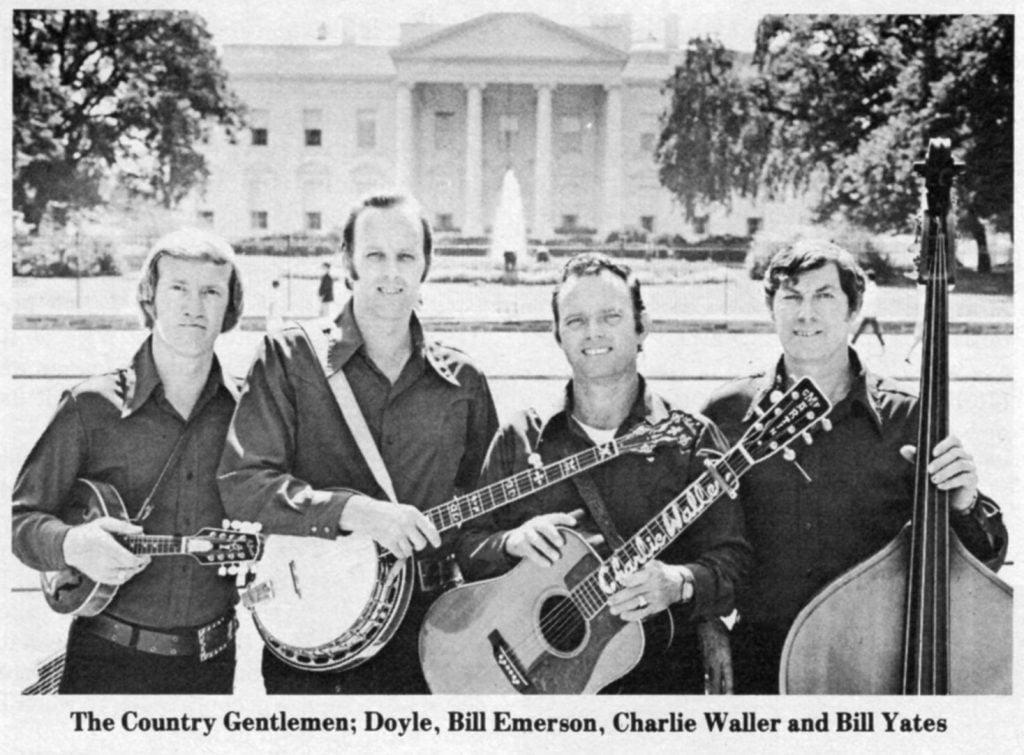

After another stint with Martin in 1969 and one more with Crowe in 1970, Doyle joined the Country Gentlemen in 1971. His mandolin playing blossomed. His choice of notes expanded remarkably, but never at the expense of his emphasis on tone, timing, and control. An individual style steadily unfolded, but never leaped too far ahead of what the Country Gentlemen’s audience had come to expect.

Doyle’s passion for the mandolin began early. “I was about four years old,” he recalls, “the first time I can actually remember hearing Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. I could tell Hank Williams, Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, and Hank Snow and all them, but when I heard Monroe…his voice and his mandolin were what struck me.

“Monroe made the mandolin a lead instrument. Now when you heard the Callahan Brothers or the Blue Sky Boys, they used the mandolin but it didn’t have the authority. At that time the fiddle and banjo is what people would listen for. But Monroe commanded attention with his pickin’. It was so different that I fell in love with it.

“At four years old I knew that I wanted to learn. When people asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I never told them ‘a policeman’ or ‘a fireman’ or ‘an airplane pilot.’ I just always wanted to play music.

“The first record we had in the house was the Flatt and Scruggs 78 recording of “I’ll Never Shed Another Tear.” The flip side was “I’ll Be Going to Heaven Sometime.” I never will forget that. I about wore the grooves off it. I loved the sound of it—the way they projected their feelings, their emotions.”

Doyle listened to a lot of bluegrass on the radio, without ever seeing the performers. The Cas Walker show from Knoxville featured Carl Story, the Webster Brothers and the Brewster Brothers. The Stanley Brothers played live on the WCYB (Bristol) Farm and Fun Time. He also heard Mac Wiseman and Jimmy Martin with the Osborne Brothers. (When he finally did see the Osbornes in person, Doyle found they looked just as he had imagined the Stanley Brothers must look.)

Doyle was eleven by the time he started playing. “I learned to play melodies on the mandolin,” he explains. “I didn’t know what key I was in or what I was doing, but I could play the melody. I probably went a year without knowing a chord.

“I wanted to play exactly like Bill Monroe—that was my wildest dream. I listened to his records over and over, and I got to where I could play pretty close to his stuff—‘Close By,’ ‘Uncle Pen,’ ‘New Muleskinner Blues.’

“The one I couldn’t get was ‘Roanoke.’ I never got that exactly like he did it. I tried—I’ve even tried in later years, but it’s beyond me. It’s his and I’m not gonna fool with it!”

Doyle has given a lot of thought to what makes good music, and good mandolin playing in particular. In his view, “the new people that are coming along now haven’t really taken time to listen to what Bill plays.

‘‘Bill doesn’t play as many notes, but there’s a difference in the way he projects. What he does with one note might take me two or three to do.

‘‘I wish people could understand what he’s doing, because it’s so unreal. It’s just a little riff that he’ll do and suddenly you’ll say, ‘Wait a minute!’ And you back up the record and listen to it again. And he’s just done a smashup riff that you’ve got to listen to. It’s the way he delivers.

“After I got over the fact that I could never play like Monroe, I felt in order to be somebody I’ve just got to play what I feel—the way I want to play. I didn’t come up with a totally different style. I don’t copy anybody, but I’ve learned from everybody.

“If I hear Red Rector do a little lick, or if I hear you do one, I’ll say, ‘Hey, that sounded really good!’ I’ll take a little from here and a little from there and put it into the way I feel. You never get too old to learn.”

It would be hard to find anyone in bluegrass whose playing comes across more clearly and distinctly than Doyle’s. As there is quite a bit of variety among mandolin players on matters of technique, Doyle’s thoughts are informative for anyone who even occasionally picks up the mandolin for fun.

“I like to play real clean,” he asserts. “If you can’t play it clean, then don’t play as much. Play a little less so people can hear it.

“The hardest thing when I was getting started was getting as much volume on my up strokes as on my downs. If you don’t have the same volume on the ups and the downs, you have highs and lows in your playing. You can’t be clean that way.”

Right hand position can also be crucial to achieving good timing and an even sound. “When I first started playing,” Doyle remembers, “I had my wrist completely off the mandolin, and my control was just shot. I couldn’t get a good clean tone out of it.” New he rests the inside of his forearm against the mandolin and lets the wrist just touch—but not press against—the bridge.

The pick motion Doyle uses comes, as it does with a majority of mandolin players and guitar flatpickers, from the wrist. However, he points out that some players—like Sam Bush and Doc Watson—get excellent results with a stiff wrist. Their pick motion comes instead from the forearm. “And Ricky Skaggs,” Doyle adds, “his wrist is not as flexible as you might think. It looks complicated, but it comes out sounding super. That probably does away with the myth that you have to play with your wrist. As long as it comes out good, that’s the important thing.”

Asked about players besides Bill Monroe whom he listened to a lot, Doyle thinks of several. First is Paul Williams, the great singer and mandolinist who, along with J.D. Crowe, played on much of Jimmy Martin’s best recorded work. “I got after Paul’s style real heavy,” Doyle volunteers, “after Jimmy showed me some of the stuff Paul had done. ‘Ocean of Diamonds’ is a classic intro to a song. It took me forever to learn how to play that. I never did get it exactly.

“I listened to Bobby Osborne, too. Then later on I got listening to Frank Wakefield—he just blew me away. “I always liked Jesse McReynolds, but I never did get into the crosspicking. I could never get enough drive. I do a little crosspicking, but mine is two strokes down and one up. His is one down and two up.”

Of course playing is only a part of bluegrass. Singing is at least as important—perhaps more so. As one who has done more than his share of outstanding tenor work, Doyle’s thoughts on the voice are also of interest. “I’m not the world’s highest tenor singer,” he acknowledges. “I can hit a high ‘b’ note fairly easily when I want to get it. And I do it occasionally, when I want to. But I wouldn’t do it all the time. If I did, after a couple of years. I’d have to drop it to a ‘b flat’ and then maybe to an ‘a’.

“You can push your voice, but if you’re going to use it for a while, treat it like you would your car. Take care of it. Otherwise you can waste yourself in a hurry.”

One of the most important tasks faced by any band is finding good material. While most bands play at least some songs previously recorded by other artists, every band needs strong material that is not associated with another bluegrass group. The more unique its selection of material, the more quickly it develops a distinctive image in the minds of an audience.

Once a song is selected it must be arranged. Should it be done fast or slow? Which instruments should take breaks? Will there by harmony vocals? If so, how many voices? Should one chord be substituted for an existing chord to change the feel? And so on. The sum total of song selection and arrangement has much to do with what is thought of as a band’s style.

Doyle grasped the importance of material selection and arranging early. When he first joined J.D. Crowe the band was mostly doing material from classic recordings of other bands. It leaned especially toward Flatt and Scruggs material from the 1950s.

“We were just playing some bars and private parties for the people that owned the horse farms around Lexington,” explains Doyle. “We weren’t really thinking about style or being different. But I knew if we ever got really serious that we’d have to make some changes.”

When he returned to J.D. after his second stint with Jimmy Martin, Doyle broached the subject. “I said, ‘Look, I think we ought to really concentrate on having a sound people can recognize as being who we are and not being a copy of something else.’ And even though we did “I’ll Stay Around’ and ‘Why Don’t You Tell Me So,’ we didn’t do it like Flatt and Scruggs. We wanted to try to relate how we felt about it, the way we understood it. And we took songs like ‘Sin City’ that the Flying Burrito Brothers did and ‘Christina’s Tune,’ which everybody calls ‘Devil in Disguise.’

“When I went with the Gentlemen, I didn’t have to look for any style. It was there. All I had to do was adapt and make it sound like the style they’d created.”

Adapting, however, took some work over a period of time. Doyle explains it by remarking, “Jimmy Gaudreau and John Duffey (the band’s previous tenor singers) had similar tones. My accent is different and my voice is not toned like Gaudreau or Duffey—either one. So I had to work on cutting off a note here, or rounding out the sound there—that kind of thing.

“You always sing with the lead singer,” Doyle continues. “You do it like he does. If he says ‘Ah’ (for I), you say ‘Ah’. If he says ‘Aye,’ you ‘Aye’. It took me maybe a year to where I felt really good with it.”

After a time Doyle began locating most of the Gentlemen’s new material. As Charlie Waller did most of the lead singing, it was in large part a matter of finding songs that were suitable both to Charlie’s voice and to his temperament as well.

Among the songs Doyle introduced to the group were Steve Goodman’s “City of New Orleans” (before it was a pop hit), Kris Kristofferson’s “Casey’s Last Ride” and Willie Nelson’s “Bloody Mary Morning.” In many cases Charlie would be initially skeptical about a new song, but, as with “Casey” and “Bloody Mary Morning,” once he got accustomed to the new song he would do an outstanding job with it.

Quite a few of the songs Doyle brought in were from his own early musical experiences. “When I came to work with the Gentlemen, they didn’t do a lot of quartet singing, the way we did later on. From time to time,” he explains, “I’d take in a quartet I’d heard Dad singing. One time we decided to do an a capella song for no reason at all other than we liked it. The Gentlemen had never done anything like that.

“That song, ‘Lord Don’t Leave Me Here,’ sold more records for us! We’d do it at shows and we’d sell albums as fast as we could hand them out—with all four of us working at it!

“So I feel like I took a lot of this east Tennessee music with me up there and introduced it through the Country Gentlemen. They were considered a northern bluegrass band, and I feel like I put some roots to their music. Not to take anything away from them—I don’t mean it like that. But the kind of music we were doing when I left—in comparison to when I went with them—is different.”

At one point Doyle came close to cutting short his career with the Country Gentlemen, and with the bluegrass world they belonged to. “Around 1972 or 1973,” he explains, “we left the Rebel label and went to Vanguard. At that time, we were as hot as anybody in bluegrass. Vanguard had Doc Watson, Dave Loggins, Joan Baez, and were familiar with acoustic music. They had caught our act at Max’s Kansas City. They talked a real good story and we felt they’d jump on it and really promote us.

“It didn’t happen. They just fell really short of any expectation we had.

“We played Philharmonic Hall before it was Avery Fisher Hall—us and the Osbornes and Don Reno were the first three bluegrass groups to ever play there. Our record company (whose office is quite close by) didn’t even bother to send anybody. That first Vanguard album left a bad taste in my mouth about music in general.

“Bill Emerson (who had played banjo with the group at different times since it started out in the 1950s) got real dissatisfied, and arranged to go into the Navy. I think he wanted to establish some security for his wife and three kids.

“I agreed to do it with him. We were both going as chief petty officers. I enlisted, took the physical, and all I had to do was to be swom in with him.

“Then we played the McClure Festival; it was supposed to be our last show. And I thought, ‘We’ve been struggling since 1963 to turn these people on. Are you going to turn your back on them? Because a year after you’re gone these people aren’t going to remember who you are.’

“So I just realized then that I couldn’t do it. I think I’d have been really miserable if I had. So I bowed out. I told Charlie and (bass player) Bill Yates that if they wanted me to, I’d just stay on. They were just tickled to death about it.”

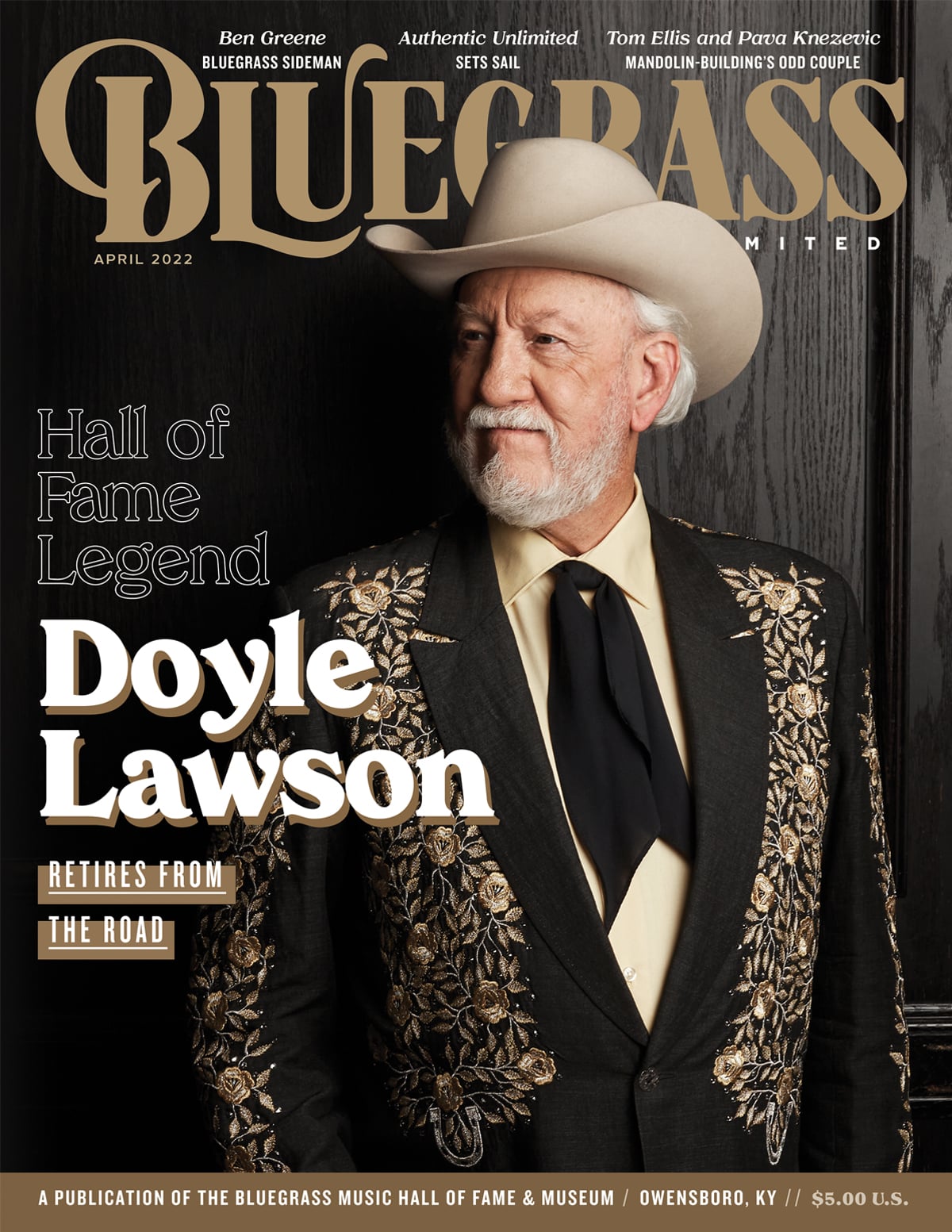

Eventually, though, Doyle did feel the need for a change, and in 1979 he decided to leave. “There’ll always be a big spot in my heart for those guys,” Doyle asserts. “I’ll always feel indebted. It was a great asset to my career to be able to go with the Gentlemen.

“But we had gotten to a point where I felt I was in a rut—where I wasn’t being as creative as I thought I could be. I wanted to try something a little different—maybe a little more commercial then we were at that time. Like Charlie said—they had their sound, their style, and he wasn’t really interested in experimenting with it. And I respect that; but I wanted total freedom for a change.”

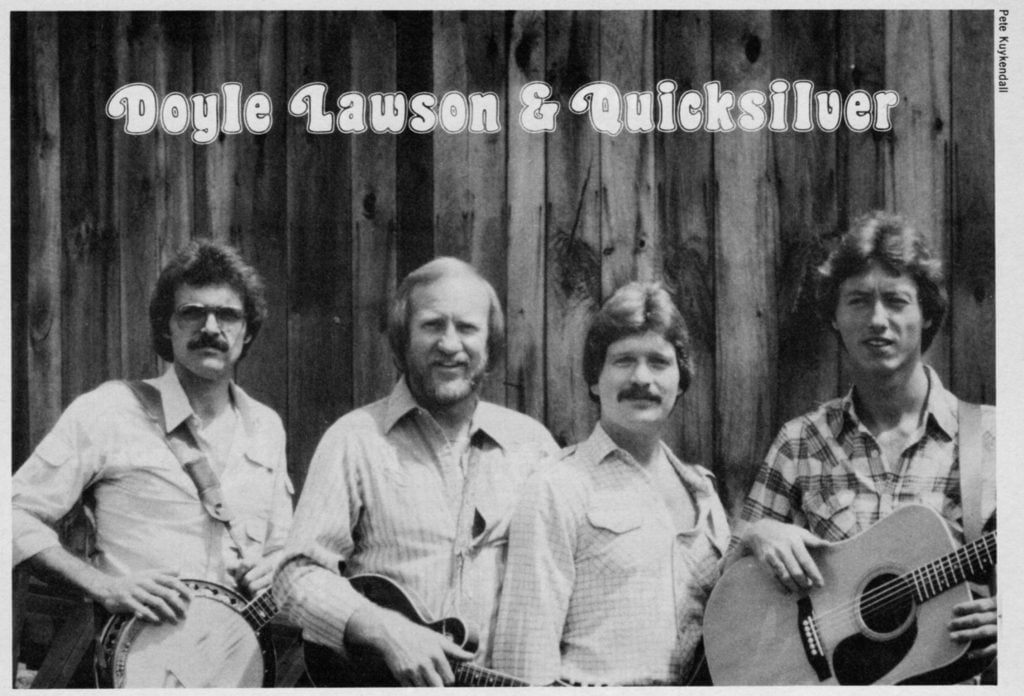

The vehicle for Doyle’s ideas took form as Quicksilver, formed in April 1979. The remaining new band members were North Carolinians in their twenties who had been fans of Doyle’s for many years. The three, Terry Baucom (banjo), Jimmy Haley (guitar) and Lou Reid (electric bass) had known each other for quite some time, and were delighted at the opportunity to pick with Doyle as well as with each other.

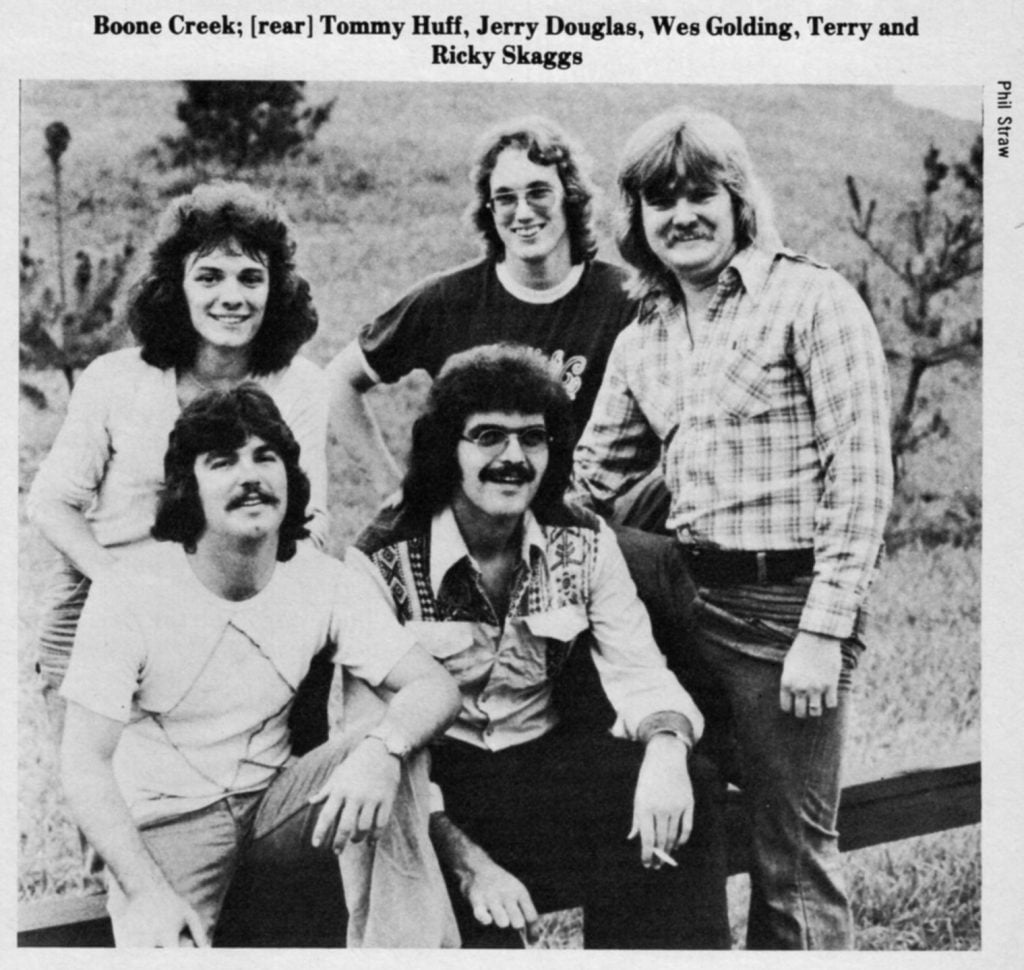

Terry Baucom is perhaps best known of the three to bluegrass fans. He performed and recorded on fiddle with Charlie Moore and also fiddled on Ricky Skaggs’ solo album “That’s It.” Terry later worked with Ricky in the Boone Creek band, this time as banjo player.

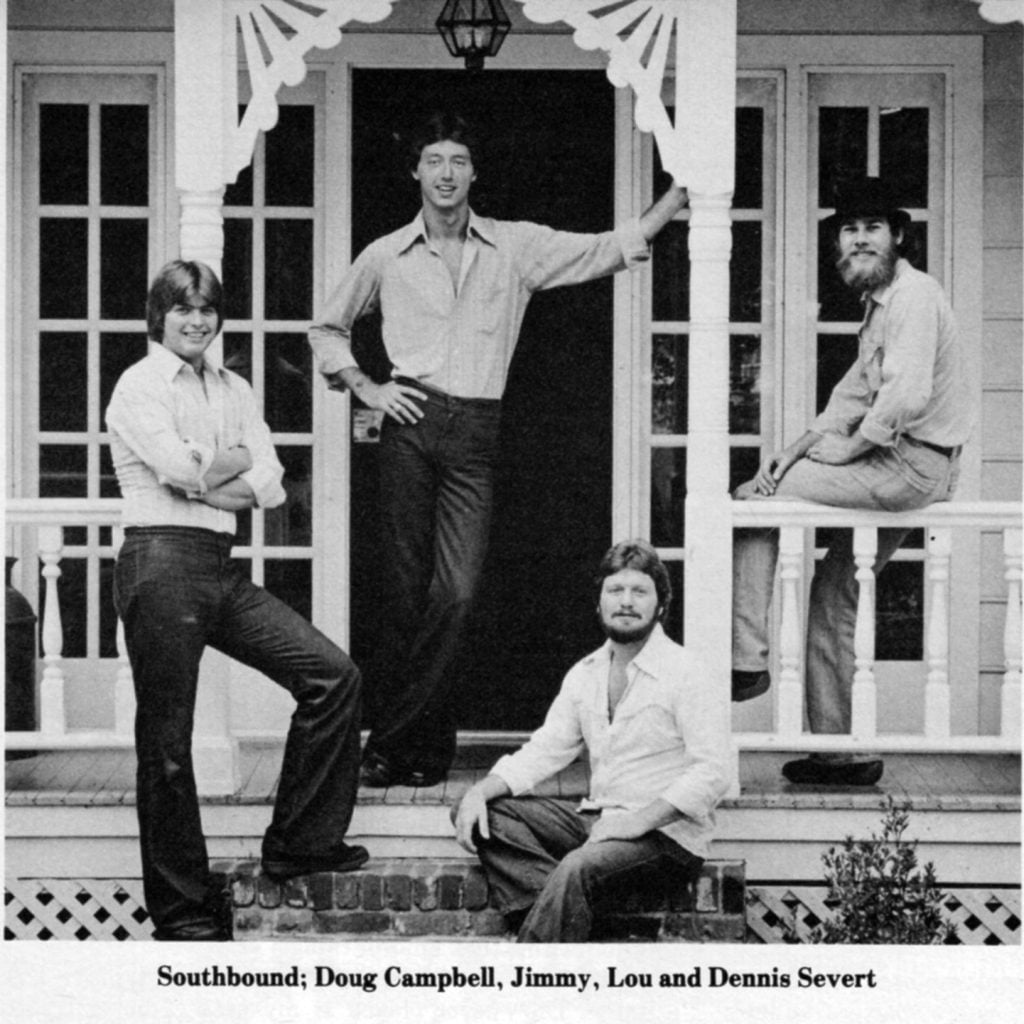

The fathers of guitarist Jimmy Haley and bass player Lou Reid used to play together at, as Jimmy puts it, “dances, corn-shuckin’s and liquor drinkin’s” in the rural area north of Winston-Salem. The two boys, however, didn’t meet until high school. Lou played rock and roll, but gradually found himself being won over to bluegrass. After graduating from high school they began working at music in earnest. Their group, called Southbound, recorded two albums for Rebel, one of which has been released.

Each of the three has distinct recollections of early musical influences. “I grew up listening to Bill Monroe,” says Terry. “My father was big on him and Flatt and Scruggs. I always liked Crowe and Scruggs on banjo—Bobby Hicks and Vassar Clements on fiddle.”

Jimmy started out listening to Flatt and Scruggs and first learned to play guitar in the Lester Flatt thumb-and-fore-finger style. After a couple of years Doc Watson and Tony Rice captured his imagination, and he switched to flatpicking.

Lou, however, was older when he began paying attention to bluegrass. “I listened to J.D. Crowe (with Doyle) and the Country Gentlemen, and that’s about it.”

There was, however, a common denominator of material they were all drawn to. “I knew these guys when we first started,” drawls Terry in his quiet bass voice. “Back then we were hot on J.D. Crowe—‘I’ll Stay Around,’ ‘Born to Be With You’—that kind of thing. That was drivin’ us pretty crazy at the time. We studied that for a while didn’t we?” He laughs and Jimmy and Lou agree heartily. “Yeah, that’s something I grew up on and I loved it.

“We stress rhythm a lot, don’t we,” asks Terry, and again gets vigorous agreement. “On top of the beat, that’s where it’s at. You keep it from draggin’ and stay on top of the beat.

“In a four piece group everybody’s got to be tight if the whole thing’s gonna come off,” he continues. “I think I play a bigger role on the banjo now than I did in Boone Creek. Because Flux (Jerry Douglas) was there I kind of laid back—you know, just kick things off and take a break. Now he ain’t there, and it makes a big difference.”

“With four people,” adds Doyle, “you’ve got to pump all the time. You don’t have time to slack.”

And, in fact, Quicksilver does not slack. In the instrumental department it relies largely on punchy standard banjo pieces like “Nashville Skyline Rag,” “Shuckin’ the Com,” “Bugle Call Rag,” “Train 45,” etc. Terry’s awesome power dominates. His precision, drive and flawless choice of notes are so overwhelming that the near absence of surprising or unusual licks goes unnoticed. Doyle takes some extremely hot breaks, living up to his reputation as one of the strongest and smoothest players in the business. Jimmy also gets in some excellent guitar leads, although occasionally a little rhythmic tightness may get sacrificed in favor of fancy picking.

The group also does a strong job with contemporary versions of songs by the old masters: Carter Stanley’s “I’d Rather Die Young (and Be Forgotten),” Flatt and Scruggs’ “I’m Head Over Heels in Love With You,” Jimmy Martin’s “My Walking Shoes Don’t Fit Me Anymore” etc. Especially nice are some of the gospel quartets like “Happy on My Way,” “Little Community Church,” “God Put A Rainbow in the Clouds” and “Daniel Prayed.”

A sizeable component of Quicksilver’s material is contemporary in sound and not associated with other bluegrass groups. Among the best songs are “Kentucky When I Die” (by Mike Cross). “I’ve Got My Country Memories” (Jerry Lee Lewis), “I’ll Be With You” (Bob Hooker) and “Come On Over” (the Bee Gees). They also have some lovely gospel quartets of their own which are scheduled for release on their next album.

There is a smoothness and a slickness to much of the contemporary material which is reminiscent of some of the better performers in the pop/country field- something like a Don Williams with bluegrass instrumentation. Jimmy Haley’s lead voice is especially well suited to this style and Doyle often uses the mandolin to create a texture rather than to play the melody on breaks.

Quicksilver’s chief concern is getting across to the audience. “People have to be able to identify with what you’re playing,” explains Doyle. “You want them to be able to hum a little bit—maybe sing eight bars of it—just in some way or another to relate to what you’re doing.

“A couple of years ago,” he goes on, “everybody was into all these stops and chords progressions and stuff like that. But the majority of the public are not accomplished musicians. They can’t figure out an arrangement if you have 17 change-ups here and two stops there and that kind of thing.

“I can play more than I play. I’ve never played at my peak. I never try to stick every note I know into one song. That’s not the way it’s supposed to be.

“Simplicity is the purest form of music. It’s where people can feel it and listen to it and enjoy it without trying to figure out what you’re doing.”

The group has made rapid progress in establishing its identity on the competitive bluegrass circuit. “We got together in April of 1979,” reflects Doyle. “The Sugar Hill label recorded us the following August. They had confidence enough in us to go ahead and do it. This day and time that’s almost unheard of.

“And they did a good job with it. Whatever they tell you they’ll do—they do it.” He laughs. “That’s kind of new to me.”

Current Sugar Hill releases include both that album, “Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver,” and Doyle’s earlier solo mandolin album, “Tennessee Dream.” A second Quicksilver album, this one featuring gospel material, is due out in early 1981. Current plans are for the group to return to the studio in January for work on another bluegrass album to be released around May.

Quicksilver is still young as a band, yet its progress to date has been noteworthy. There is a sense of everyone pulling together, of readiness to work hard, rehearse diligently, and to endure in good spirits the rigors of life on the bluegrass circuit. To paraphrase Doyle: Quicksilver is doin’ good and shows every indication of being determined to do better. The likely result would appear to be a steady output of increasingly solid, skillful, and entertaining contemporary bluegrass music.