Home > Articles > The Archives > Don Reno—A Bluegrass Family Tradition

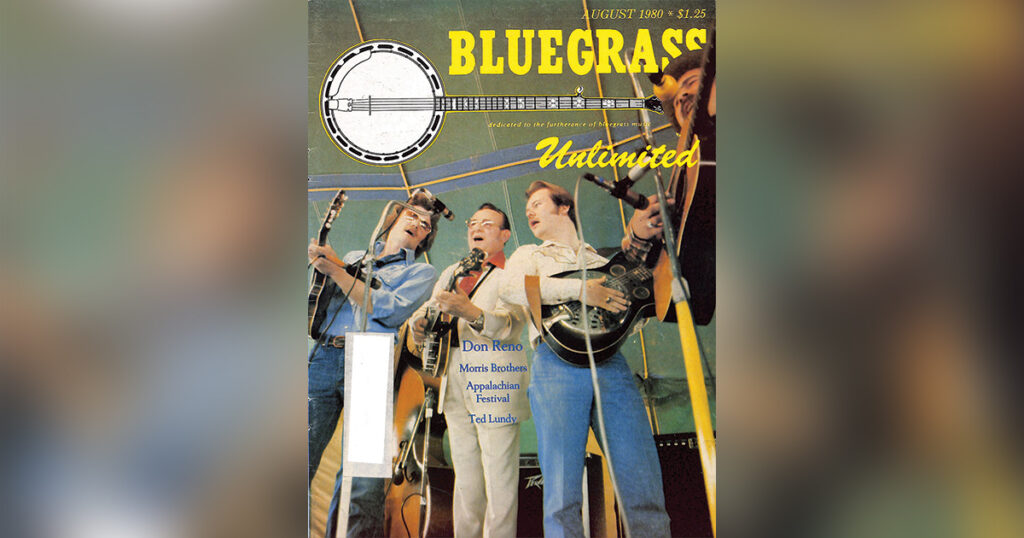

Don Reno—A Bluegrass Family Tradition

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1980, Volume 15, Number 2

Don Reno, whose middle name could easily be “Banjo” spoken with a bluegrass accent, recently marked his 40th anniversary in the entertaining business.

Fans of his distinctive style (“I just pick it,” he says.) will be happy to know that thoughts of any kind of retirement are very far from his mind.

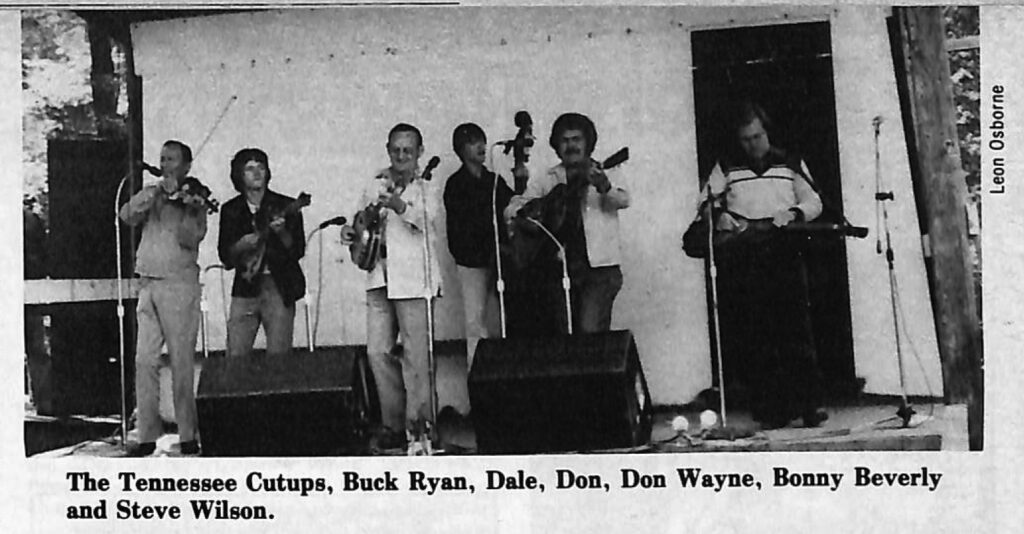

In fact, his personal appearance schedule for 1980 may be fuller than any year to date. Besides weekend shows up and down the east coast, Reno and his Tennessee Cut-ups are playing college campuses and festivals all over for longer stretches, and he’s even finding time to do some promotional work for a chainsaw firm and tour of Japan.

Whether or not it actually was planned as a means of celebration, Reno’s 40th year also was marked with the birth of his fourth child in February. His own birthday is February 21, 1927.

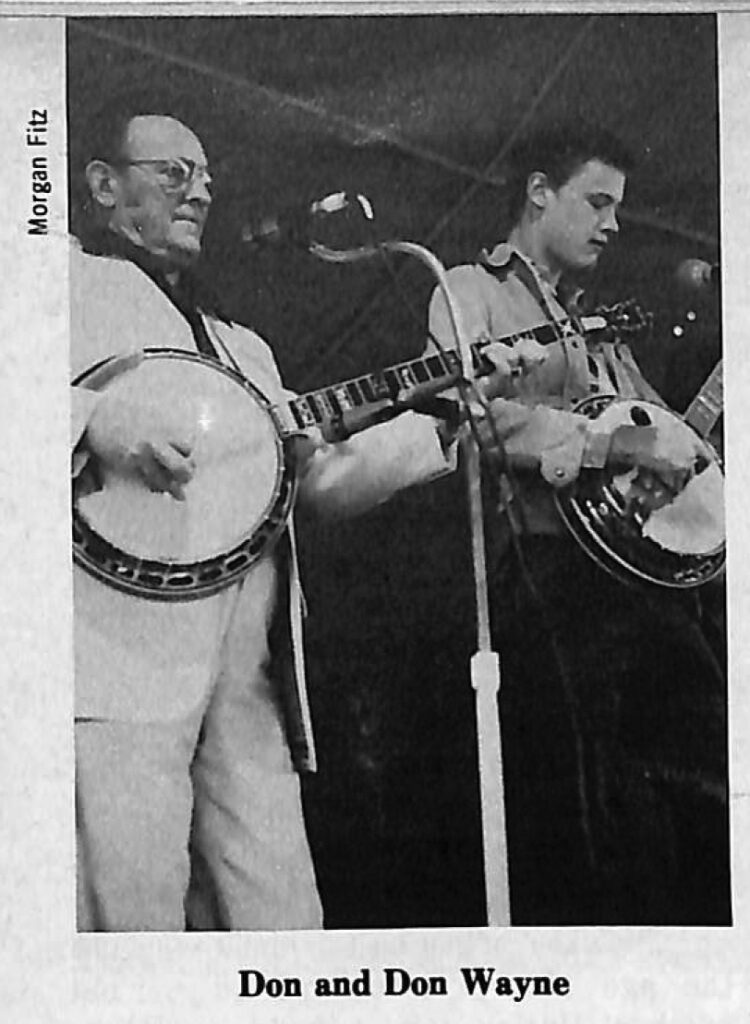

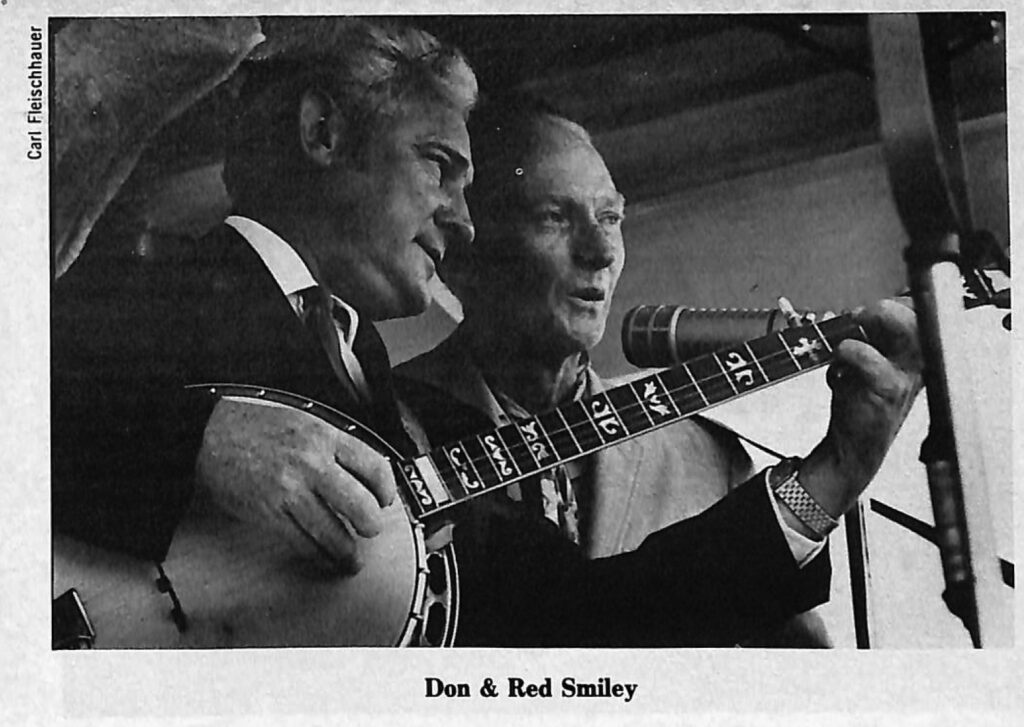

The veteran performer makes no secret of the fact that his children are important to him. The middle ones. Dale and Don Wayne, are vital parts of his current road show—a show, by the way, that Don describes as the best he’s had going since the days of his partnership with Red Smiley.

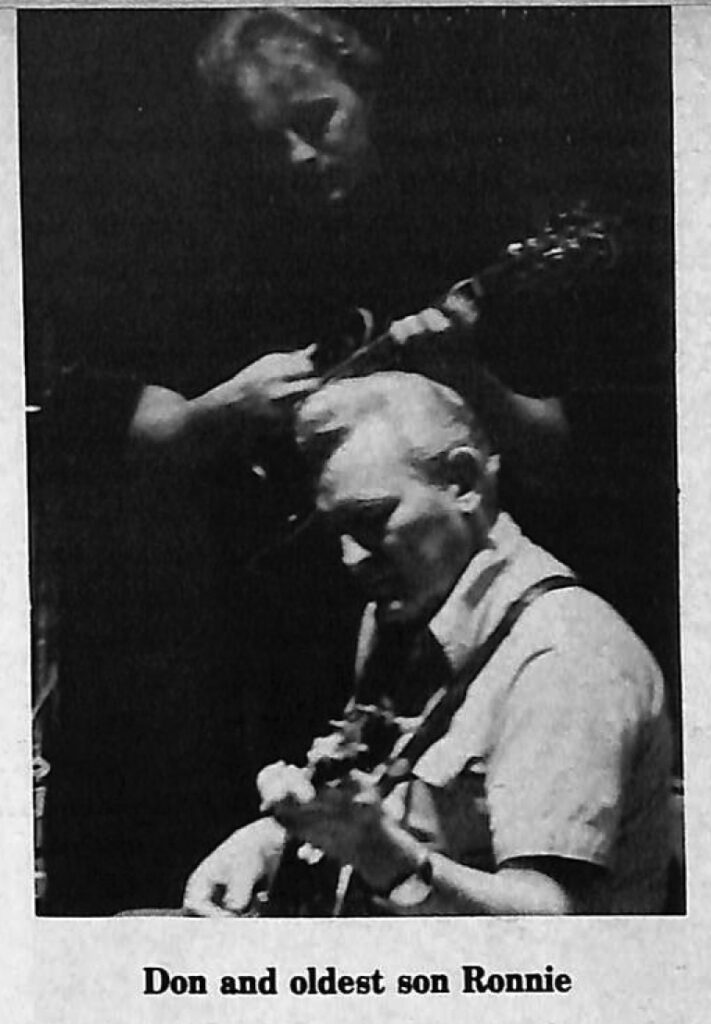

Older son Ronnie is 33 now. He worked with his father professionally from the age of seven to 20, now has his own band which fronts Merle Haggard’s shows and plays seasonal festivals, owns a song publishing company and a nice house in Hendersonville, Tennessee outside of Nashville. “He’s really got his foot in the front door out there,” his dad says.

All this makes the senior Reno justifiably proud. “I trained him well. Like I’m trying to do with the other boys.” Professing no parental prejudice, Reno points out his sons’ musical abilities: “All three are what I’d call ‘good’.”

“Don Wayne plays banjo more like I do than anybody else in the world,” Reno says of his 16-year-old. He started playing on stage with his dad about three years ago.

Dale, 18, has been a part of the Tennessee Cut-ups since 1974 when he debuted on the mandolin at Washington University.

“The boys fit in the group well,” Reno says. “Naturally, I’d like to see ’em get a start in music.”

As far as their future is concerned, he says, “Right at the present, they’re more interested in the music business than anything else. The main thing I’ve tried to make both of them learn is that you can go through school and not learn anything.”

He thinks their experiences on the road with the band—meeting new people, seeing other places and living in different environments—have taught his children a great deal.

Reno tries to work appearance dates so his sons don’t miss much school. Both of them maintain good averages and Reno says their teachers are very lenient, allowing them to take their work along when it’s necessary. “They do a lot of studying on the (tour) bus.”

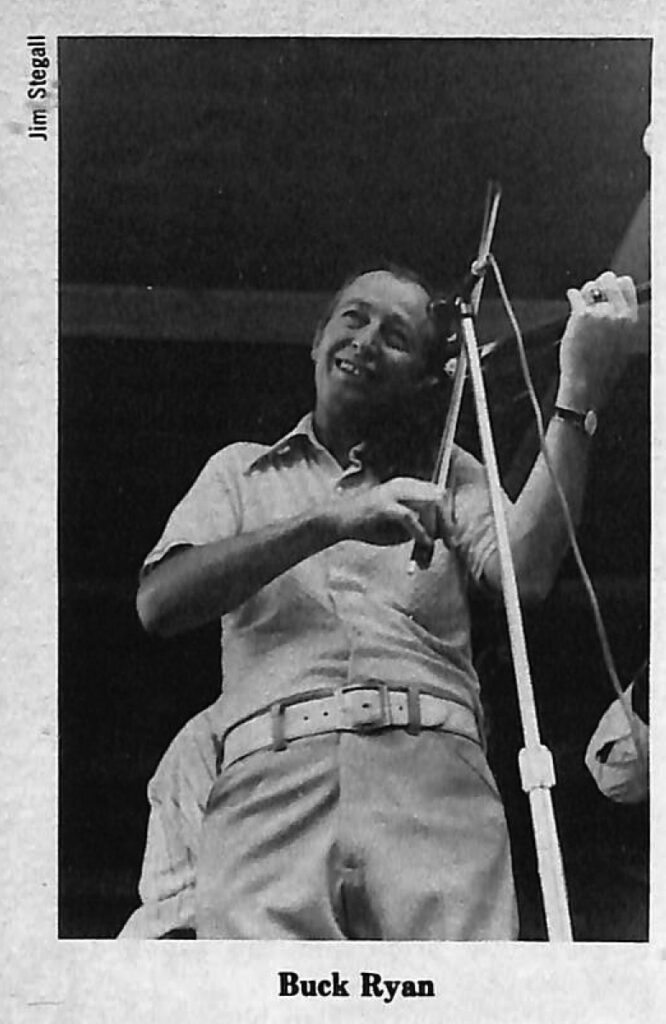

Other members of Reno’s current Cut-ups includes Buck Ryan of Stephens City, VA, who’s been putting out fine fiddle work for him some 12 years. Bonny Beverly of Rustburg, VA, is the group’s rhythm guitar man and sometimes plays twin fiddles with Ryan. Steve Wilson of Lynchburg, VA, began playing bass and Dobro with the group in April 78.

Reno describes his road shows as very versatile with appeal for both young and old audiences primarily because of the age range of the performers. He modestly explains that his average 45-minute shows have no chance of being dull since it’s possible to feature two banjos, two fiddles and two or three different types of duets and quartets—all thanks to the group’s individual abilities.

“I keep advancing them (his two sons),” the veteran performer says. “They have their own ideas and I listen to them. I get good ideas because they relate to a different group than I do.”

Reno began his own career when he was 12 years old and remembers his first paying job in Enoree, SC, well. He got $1.50 for the night’s work—all in nickels.

There’s cash in the entertaining business now, he says, but he laments the high overhead involved in keeping the band and tour bus on the road. Most of his “expense” is in terms of his own time, but he says as long as he enjoys it, he’ll keep at it.

“I never have thought I was really too good at anything,” he claims. But he thinks his fledgling sons “are going to be super musicians. They want to play.”

He points out, “I didn’t try to push them into learning. They got into it listening to me. When I heard them doing something, I tried to encourage them.”

He says he didn’t want his children to “feel pushed into the business just because I was in it. I let on like it didn’t make any difference and waited to see if they showed an interest.”

Now, the boys are able to play all the band’s instruments—and like to—because they’ve always had access to them at home. They also sing whatever’s needed for the group’s vocal numbers.

The Reno boys, their dad says, are like him. “They read a little bit of music but not enough to hurt their playing.” Like brother Ronnie, Dale and Don Wayne are showing signs of writing talent. “I imagine in the next year or so, I’ll use some stuff they’ve written,” Reno says. “I can see they both have some potential. They write both words and music.”

It was older son Ronnie’s composition “Boogie Grass Band,” recorded by Conway Twitty, that stayed high on the charts for weeks a year or so ago.

Reno himself has written a bushel basket full of songs—457 that he can readily count—but he hasn’t recorded all of them yet. Most of his have been word tunes, but two of the instrumentals have given him the most monetary satisfaction. “Dixie Breakdown” and “Choking The Strings” have been used again and again by deejays as themes for beginning and ending their radio shows. Reno’s benefits come under performance rights and he’s paid a certain sum each time his song is played on the air.

As far as word songs, Reno says he can’t name the biggest success. He thinks four have sold more widely and been sung more than others—“I’m Using My Bible for a Roadmap” which he wrote in 1951 and recorded in ’52 and ’68; “I Know You’re Married But I Love You Still,” co-written with Mike Magaha in ’55 and recorded in ’56 by Reno and Smiley (it’s also been done by people like Dolly Parton, Red Sovine, Porter Wagoner, Buck Owens and Bill Anderson); “Emotions,” written in ’53 and recorded in ’53, 70 and 75, and “Talk of the Town,” written in’50 and recorded in ’53 and ’54.

After these efforts, Reno isn’t on the entertainment road today because he needs the money. He admits that he could live nicely off royalties from previous work. He explains that over the period of years and as many songs as he has out—1200 recorded in his own name—he gets good returns. Markets in other countries continue to open up and he notes that England’s royalty payments to him tripled last year.

He enjoys the road work because he likes to work for audiences, meet people and make friends. He thinks he has everything going for him right now since he’s extremely busy and loving every minute of it. About all he gets done between show dates are resting and getting ready for the next one. But he doesn’t have anything else on his agenda: “I find I’m better off to let other projects alone and apply my mind to something I know something about.”

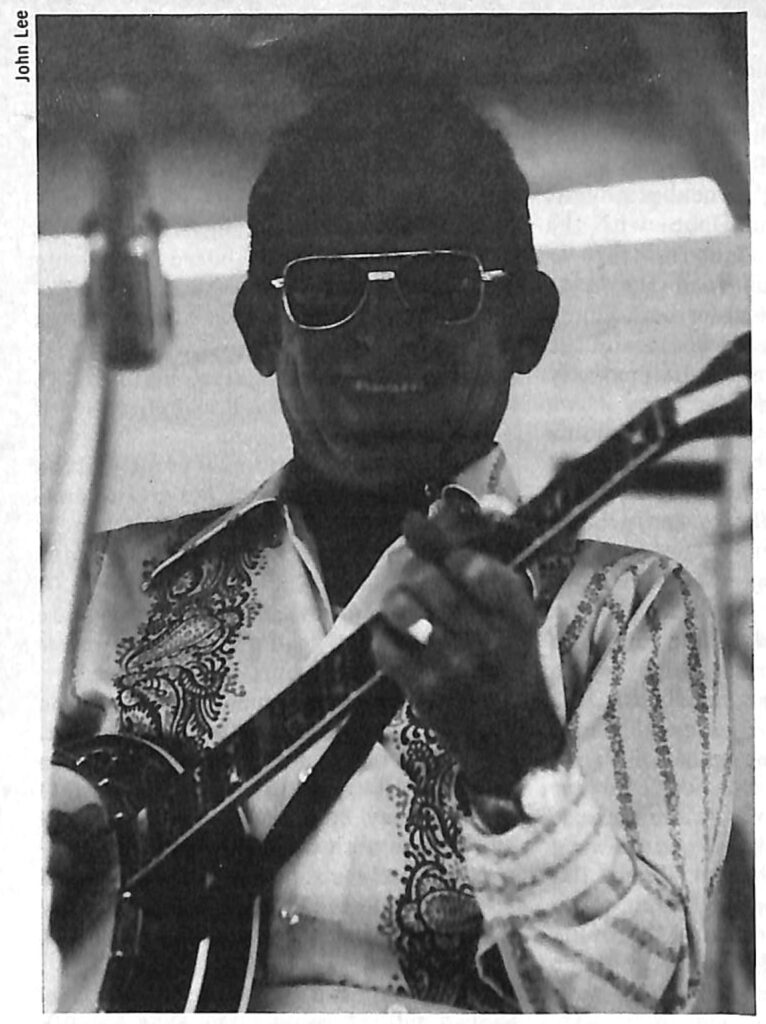

Few would argue that he “knows something about” getting music out of a banjo. He’s the one, of course, who plays all over the banjo neck without benefit of a capo.

Reno explains his early musical ambitions: “What I actually tried to do (back in the ’50s) was to play songs that could go out of the Virginias, Carolinas and Kentucky. I knew there was a market that hadn’t been reached with the five-string banjo.”

His approach to reaching those markets was to play pop ’20s and ’30s tunes—like “Limehouse Blues.” He remembers that other musicians said those pop tunes couldn’t be played on the banjo. “But it was easy and simple. Now, all these people,” he gestures gratefully, “are playing it.”

While his present road show employs “modern” bluegrass sounds and other types of music performed in that Reno-style, the man himself still favors the standby tunes from his Reno and Smiley and Reno and Bill Harrell personal appearances.

“I’ll never change my style,” he pledges. “I do a lot of country songs on stage if people request them. But I do them in my style and the sound I’ve always had.

The musician is glad bluegrass is so popular today. He thinks everything runs in cycles and it’s finally time again for people to consider where they came from and how their ancestors lived and entertained themselves. “We’re playing to the biggest bluegrass audience today we’ve ever had,” he says. And his most attentive audiences are those on college campuses. He’s happy that a lot of young people are showing an interest in bluegrass instruments and hopes this will prolong the current “roots” cycle.

Along with the trend, Reno sees the return of small schoolhouse-type shows. Those kind were his greatest joys as he made his mark in the music field. “There have been more of those shows in the last two years than in the past ten. I’d like to see them come back.”

Festivals, too, are popular with him. He thinks other people share his like for them because of the closeness and togetherness the festival atmosphere promotes between the audience and performers. “People have a particular kind of freedom (at bluegrass festivals). They can wear what they want to, talk to the stars and get their autographs and there’s no high-brow stuff like, say a concert at Carnegie Hall. People just respond to the atmosphere.”

Reno thinks the past couple years have seen a decrease in drinking and drugs at festivals. “The law has been hammered down in a lot of places. I’ve been lucky at the festivals I’ve worked, things have been under control.”

The Renos moved to Lynchburg, Virginia in September of 1976 for several reasons. His wife’s parents live in nearby Thaxton and the area provides easy access to good highways for his regular trips up and down the map.

“It’s good to be back in Virginia,” he says. He’s called Richmond, Bedford and Roanoke “home” before. Living more recently in Riverdale, Maryland, seven miles from Washington, D.C., he says, “I just kinda got the urge to get back where I could see a few trees. I can look out the window, drink coffee and watch the squirrels.”

He’s popular in the area, too. “I can’t go anywhere around here without somebody remembering me.” He’s flattered that Lynchburg-Roanoke people recall his morning weekday program over WDBJ-TV, Roanoke some 14 years ago. He hasn’t really changed all that much—maybe there are 40 more pounds of him and he wears mod eyeglasses, but his eyes still wrinkle, his voice is virtually the same and his fingers still fly about on the banjo neck on cue.

With no intention of bragging, Reno points out, “I’ve played ’em all” from hometown schoolhouses to radio and TV, barn dances, private clubs and anywhere else the crowds wanted to hear him.

He was marked for the music world at the age of five when his 16-year-old brother Harley got a band together. Harley’s Haywood Mountaineers practiced regularly at the Reno home and young Don was right at their feet. One night while the others ate supper, the youngster picked up a banjo. “To my surprise,” he relates, “I found I could pick out ‘May I Sleep in Your Barn Tonite Mister?’”

After that, Reno often prayed for rain so he could miss farm chores and practice music. A battery-powered radio brought in 50,000-watt stations in Charlotte, NC, Nashville, Knoxville and Wheeling, West Virginia, keeping him abreast of what the “real” musicians were doing. “All of these are locked in my memory as stepping stones that helped me meet millions of wonderful people,” Reno says.

In those early days, Reno’s daddy wasn’t too happy having a second musician son. He was too busy providing for his five children first in Spartanburg, SC, and then Clyde, NC, to help young Don get a banjo. “A friend of mine, J.R. Sorrells, lived over the hill and we decided if we really set our minds to it, we could make one.” The two worked some time perfecting what Reno says was “a very crude banjo, but at least I could play it.” Strings were actually screen door wire” tuned so low you might play four songs before breaking a string.”

When the elder Reno did buy him a banjo—a fine one with US flags drawn on the head—Reno sold his friend his half of the homemade banjo for $1.50.

For a time after that, Reno got interested in flattop guitar. “I followed the Delmore Brothers’ style of picking because there was none better.”

He and a friend from school, Howard Thompson, began singing together with Reno playing a Gene Autry guitar that belonged to another friend, Ed Russell. A year later, Russell learned to play guitar and Reno went back to the banjo. The following year, Joe Medford attended their school and brought along his mandolin and Lemuel Mackey played harp for the group.

The school friends played before school, during recess and after the last bell until the bus came. Their first stage performance was on a Halloween program when Reno was in the third grade. He recalls that the first tune he played on stage was “Brown’s Ferry Blues.”

When Reno was 11, his dad sold their farm and moved back to South Carolina. He traded a hog for a Kalamazoo guitar for young Don. “I got a coat hanger and made a rack that would hold a harp and started playing harp and guitar together,” Reno remembers.

After the move, Reno didn’t have anyone to play with for a while. Then ex-prize fighter Ed Tipton came along to convince Reno’s mom to let her son go to Spartanburg to begin a 6-7 a.m. radio show on WSPA five days a week.

Other musicians heard Reno’s work and he joined them to form the Tapp Brothers Band. Reno explains that two of the members were named Tapp and they had the car and PA set, so there was no question about the band’s name. Their first performance was Reno’s first paying one—at Enoree, SC.

After a few months, Reno recollects, “I was getting tired of cleaning my pants with gasoline and putting them between the mattress to press them, so I went back home to gain some weight back that I’d lost.”

His next job was with Tex Wells and his Smokey Mountain Rangers for about five months in 1940. Later, Reno joined the Morris Brothers—George, Zeke, and Wiley plus Howard Thompson. Their trio efforts was “the best I ever heard,” he remembers. “Wiley Morris was really the Bing Crosby of country music.”

When he left the Morris Brothers for a job with Arthur Smith and the Carolina Cracker Jacks, Earl Scruggs took his place. In those days, Arthur played fiddle, mandolin and guitar and his brother Sonny played guitar and brother Ralph, bass. Arthur taught Reno to read and write music.

By now, Reno was playing a $50 Gibson Mastertone banjo. Earl Scruggs took a liking to it in 1948 and convinced him to swap it for the 1934 Gibson Mastertone Reno still plays.

The Smiths left the Spartanburg radio station in late 1943, but the management asked Reno to stay. He formed a band with Howard Thompson on guitar and singing, Shorty Boyd, fiddle, Mary Lou Morris, bass. Miss Morris left very shortly to be married and John Palmer of Union, South Carolina took her place.

About this time, Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys came to Spartanburg with a tent show and tried to hire Reno. But the young musician said he’d rather lie about his age and join the Army. He told Monroe that if the Army didn’t take him, he’d make it on out to Nashville. Uncle Sam did take the 17-year-old and sent him to the horse cavalry at Ft. Riley and later to China, Burma and India where he served honorably with Merrill’s Marauders.

Earl Scruggs took the banjo position with Monroe.

Reno remembers hearing Monroe’s band—Scruggs on banjo, Chubby Wise, fiddle, Lester Flatt guitar, Cedric Rainwater, bass and Monroe, of course, mandolin—on the Opry when he got out of the service. “They really sounded great. None will ever be better.”

Reno opened a grocery store in Buffalo, SC, with his brother then and played electric guitar for weekend dances with John Palmer and the Pruitt Brothers. Paul Howard offered him a job on the Opry, but Reno said he wanted to get back to the banjo and didn’t take it.

He’s stuck with the five-string since then, except for the times when appreciative audiences holler him into doing some tunes on the flattop guitar.

In March of ’48, now 21, Reno and his Carolina Hillbillies were playing on WSPA, Spartanburg when he heard Monroe playing without Scruggs. He left at once for Nashville only to find the Blue Grass Boys were playing Taylorsville, NC, the next night.

Reno recalls, “I got to Taylorsville just as they were starting their show. I went backstage, took my banjo out of the case and walked on stage and started playing. Bill said, ‘Boy, I’ve been trying to find you.’ And I said, ‘Well, I finally made it.’”

“I had a great time working for Bill. He really taught me a lot. We worked hard and enjoyed every minute of it.”

In 1949, Reno quit Monroe’s band to form his own with a nephew, Verlon Reno. This was the birth of the Tennessee Cut-ups. In late December, Reno, Verlon and Bill Haney met Tommy Magness, Red Smiley and Al Lancaster at Roanoke’s WDBJ for a one-hour, unrehearsed radio show. Lancaster left a month later and Irvin Sharp took over duties on the bass and worked out a comedy routine with Reno.

The program continued until June, 1950, when Verlon drowned near Clifton Forge, Virginia. After that, Smiley started singing duets with Reno in that special combination of voices that touched the listening public’s heart. Even today, Reno hesitates to compare anyone with Smiley.

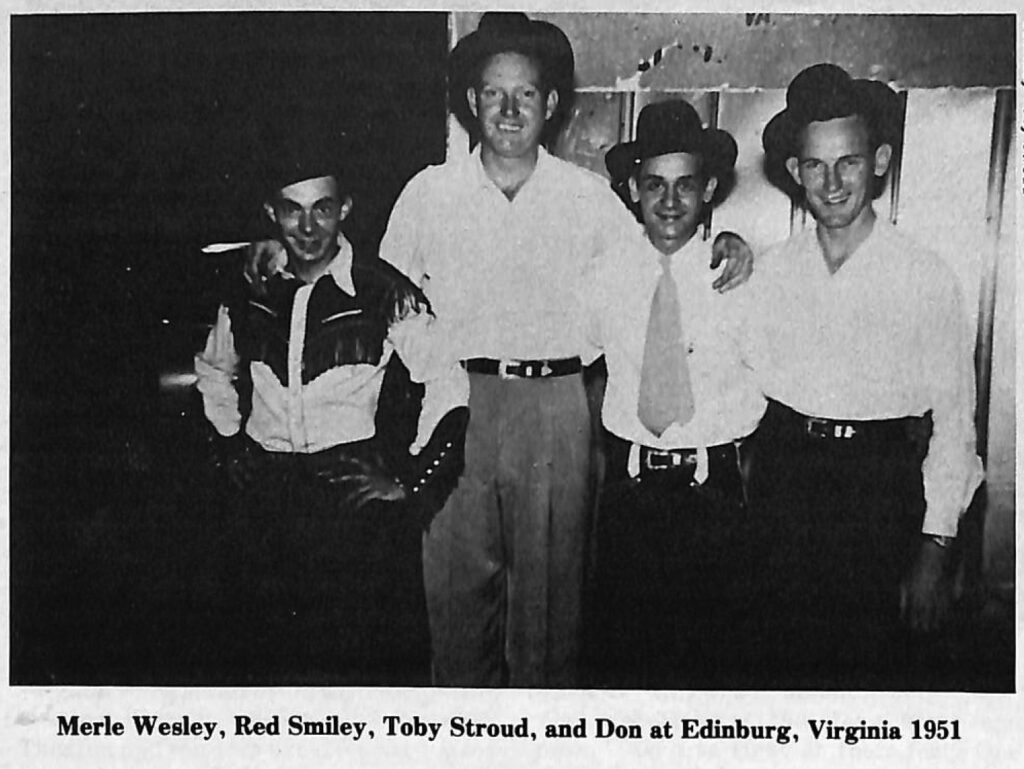

April of 1951 saw Reno leave Roanoke for Wheeling, West Virginia and Toby Stroud’s Blue Mountain Boys. By September, he was back in South Carolina to look after his sick father and Smiley was with him. Their group became known as Don Reno, Red Smiley and the Tennessee Cut-ups. They recorded 16 songs for King Records in January, 1952, but things were bad in South Carolina at the time and the group had broken up before the first record—“I’m Using My Bible For a Roadmap”—was released. Smiley had gone to Asheville to work for the state and Reno was back in the grocery business.

Reno worked briefly with Arthur Smith again, continuing to record with Smiley, until May, 1955 when Reno and Smiley got the Cut-ups together again to play the Old Dominion Barn Dance in Richmond.

Before leaving Smith, Reno helped him record “Feuding Banjos” on MGM. In latter years, the title was changed to “Dueling Banjos” and it was used as the theme for the movie, “Deliverance” and made record charts in two fields.

In later 1955, Reno and Smiley got Mack Magaha of Ware Schoals, South Carolina and talked John Palmer into leaving South Carolina to go to Richmond for regular Barn Dance appearances. They taped radio shows every Saturday evening to be played during the week over WRVA, Richmond and did a TV show every Tuesday night over WXEX, Petersburg.

Comedy got into their act when Magaha’s mother made Smiley a dress and they bought him a wig in New York when they played the Arthur Godfrey Show. Smiley’s name was Pansy Hot Rod, Palmer became Mutt Highpockets, Magaha was Jeff Doolytater and Reno kept the name Chicken Hot Rod given to him by Tommy Magness in the early Roanoke radio days.

The comedy skits were billed as “Chicken and Pansy Hot Rod and the Banty Roosters.” Reno thinks, “a lot of people still remember the comedy skits that have forgotten Reno and Smiley.”

In 1955, Bill Harrell went to work with the group as a mandolin player and they worked with Jimmy Dean and the Texas Wildcats on a Washington TV station four hours every Saturday night.

In April, 1956, then-manager Carlton Haney decided they should go back to Richmond for radio exposure on the Old Dominion Barn Dance. Reno figures they got pretty exposed—“We worked 342 days in 1956.”

In December, the Cut-ups were back in Roanoke at WDBJ-TV with a first—the 6-7 a.m. Top of the Morning Show. They’d all moved to Roanoke and were driving back to Richmond every Saturday night until the spring of 1957. That year, their morning TV show was so popular, they were given another half hour. They also took over the WDVA Barn Dance in Danville on Saturday nights and started a TV show in Harrisonburg on Wednesday nights in 1958. In 1960, the Cut-ups were playing regular dances at the Verona Roller Land Skating Rink, and running themselves ragged. “Many times, we just barely made it back for our Top of the Morning show in Roanoke,” Reno remembers.

1961 saw Reno and John Palmer in the automobile business in Roanoke. They were still playing music as usual but by November, 1964, Smiley’s health was getting worse and Reno decided to leave Roanoke in an effort to get his friend and partner to quit work. Smiley didn’t get the hint, however, and kept the WDBJ-TV show, stopping only personal appearances.

Reno took his family to Bedford and says he thought for two weeks about getting out of the music business. He couldn’t make the break, though, and got up another band to tour until September, 1965. Then, Reno says, the Bluegrass Depression hit. He and son Ronnie did some radio work around Richmond for a while and then the family moved to Nashville in June, 1966. By that December, Reno and Bill Harrell became partners and Don moved to Riverdale, MD, where he stayed until moving to Lynchburg.

Smiley had officially retired in 1968 but Reno says. “He was getting music fever again,” so Red joined the group until he died, January 2, 1972.

“The last two years and five months that Red worked with me and Bill Harrell were the happiest years we spent together,” Reno recalls. In February, 1970, they did the “Reno and Smiley Back Together Again” album for Rome Records. May 18 and 19, 1971, Smiley completed his last recording with the group. Reno recounts sentimentally that the last song was, “Wreck of the Old 97.”

“Fate,” he says, “must have prompted Ray (Davis at whose studio the recording was made) to name the album “The Letter Edged in Black’—a song that is on the album.”

After Smiley’s death, the Cut-ups didn’t pick up their instruments for six weeks. Then, in May, 1973, another emotional shock tore the group when Ellis Padgett, bass player, died suddenly.

Three years ago, Bill Harrell was injured in an automobile accident and Reno found himself without a singing partner again. Reno’s advice to his musically- inclined children has been to stay with the fans, make friends and “let people know you’re down to earth. If they like your playing, just appreciate it. Don’t let it go to your head.”

He and his boys have cut a family album earlier this year. “It will feature everybody and then we’ll all do some tunes together.”

About his sons playing with him regularly, Reno summarizes, “It’s nice to have your family with you. I’ve never had any trouble with the boys. I know what they’re doing and I can stay close to them.”

Dale and Don Wayne seem to enjoy “the whole shooting match” of the music business, Reno says. They are at least making a lot of friends, enjoying personal relationships with teenagers in their audiences—especially girls aged 8 to 18, he adds. His boys have good personalities and are very friendly. This, he emphasizes, can’t hurt his band’s acceptance.

He derives a lot from his sons’ enthusiasm. ‘They are energetic as young people will be,” he says, and they jam a lot on the road, between tours and after scheduled performances.

Another four or five years will likely find Dale and Don Wayne out on their own, their dad figures. Then, will he think more of retirement? Well, there’s another baby Reno and….