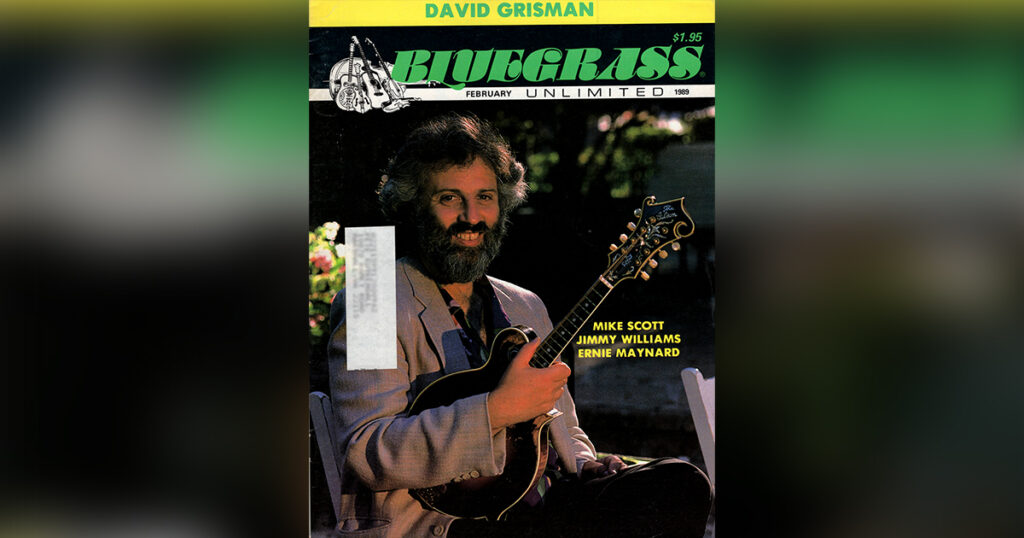

Home > Articles > The Archives > David Grisman

David Grisman

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1989, Volume 23, Number 8

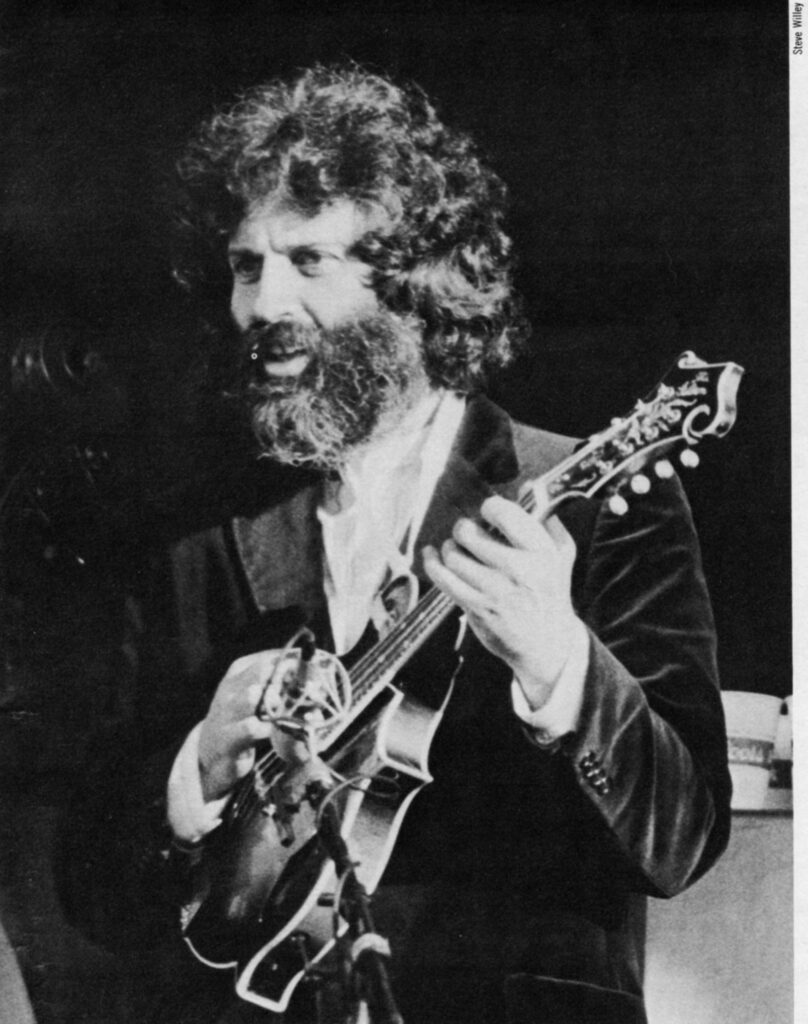

David “Dawg” Grisman is back in the bluegrass once again with a new two record album featuring the likes of Red Allen, Del McCoury, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Doc Watson, Ricky Skaggs, Herb Pedersen, Bobby Hicks, Tony Rice, Curly Seckler, J.D. Crowe, Sam Bush, Mark O’Connor, Jim Buchanan, Porter Church and others. “Home Is Where The Heart Is” (Rounder Records 0251-0252) showcases Grisman with various combinations of the above players and singers on a double dozen traditional bluegrass and folk songs.

Doc Watson joins Grisman for several Monroe Brothers-esque duets on songs like “[Have A] Feast Here Tonight” and “My Long Journey Home.” Curly Seckler, veteran of bands with Charlie Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs and Flatt’s Nashville Grass, along with Ricky Skaggs and Alan O’Bryant added tenor vocals. Red Allen, Grisman’s band leader in Allen’s mid-sixties Kentuckians, came out of retirement to sing traditional bluegrass chestnuts like “Highway Of Sorrow” and “Sad And Lonesome Day.” Del McCoury lent his powerful pipes to Bill Monroe’s “True Life Blues” and Charlie Monroe’s “I’m Coming Back But I Don’t Know When.” The list of excellent players and great songs goes on and on.

Grisman himself sings on nine of the cuts, usually in the baritone slot, except for lead vocal on the novelty song “I’m My Own Grandpa,” the album’s title song “Home Is Where The Heart Is,” and “Salty Dawg Blues.” His mandolin playing is exceptional, very much in the traditional bag with few traces of his patented Dawg sound.

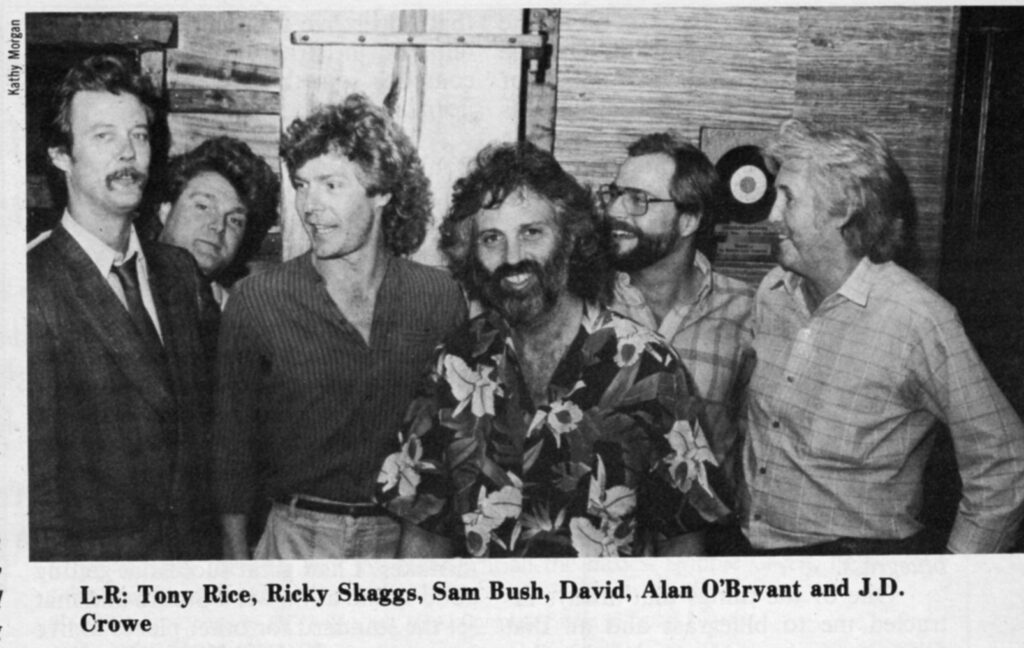

Grisman assembled over twenty guitarists, fiddlers, singers, mandolinists, banjo players and bass players, sort of his own bluegrass repertory company, to complete the project. Most were old picking partners from Grisman’s bluegrass past, though some, like the Nashville Bluegrass Band and Curly Seckler, were relatively new acquaintances. Alumni from his previous bluegrass recordings are strongly represented by the likes of Tony Rice, Ricky Skaggs, Herb Pedersen and Jim Buchanan. Gathering them together was logistically difficult but over the course of many months and miles traveled Grisman was able to pull it off.

I recently spoke with David about “Home Is Where The Heart Is” and his long standing passion for bluegrass music. As usual he was juggling several projects at once, among them supervising the building of a multitrack studio in his Mill Valley, California, home which he hopes to employ for future bluegrass recording projects. Between hammer blows from the basement/studio below we chatted.

How did this album project begin?

Rounder thought it would be a good idea for me to make a bluegrass album, two in fact, and I wanted to record with a lot of different people. The original concept was to get some of the original musicians that played this music together, many that I had never played with. For several reasons, mostly economic, they weren’t available so I turned to younger guys currently playing the music.

We decided to go for two albums since we could save on expenses. Once you have, say, Del McCoury in the studio, it’s almost as easy to record five tunes as it is to record three. Rounder said, “We’ll put one album out now and hold the other back for a year.” That sounded OK, but as I was doing this stuff I got more interested in putting it out all at once. I don’t like to sit on material and since I had so many different people involved I felt it would round the project out to release it as one package. I also thought that it would get more attention as a double album. And, I like albums you can open up and see pictures.

How did you record the different groups?

All at different times. The first session I did with Red Allen and Porter Church in May of ’87. I had a gig in Columbus, Ohio, and a day off the next day. I got in touch with Red and he suggested a studio near his house in Dayton. Porter drove up from Virginia and we went over to Red’s house and ran through a bunch of tunes.

Was (fiddler) Stuart Duncan at that session?

No. I planned a lot of the sessions without a fiddle on purpose. Logistically and musically I thought the fiddle could work as an overdub. I left holes for the fiddle. I figured that way I could concentrate on the rhythm and singing. Also it’s economics. I was trying to get a lot accomplished for a minimal amount of budget. Getting all these different people on a record can be very expensive. I avoided flying guys out figuring I’d do the project over a span of time and wait until I was either near them or they were near me.

Next I got together with Del McCoury and Herb Pedersen. Del was in northern California for the California Bluegrass Association’s Grass Valley Summer Festival. In early July of ’87 Doc Watson was out here doing some shows and I just happened to read about it in the newspaper. We called Doc up and went into the studio. A few weeks later we did the session with the Nashville Bluegrass Band, who were actually the first players I asked to appear on the record. I like that band so much for their traditional vibe. Then I did two more sessions in Nashville with Tony, Ricky, Curly, Jim Buchanan, J.D. and Sam Bush. As we were packing up, Mark O’Connor dropped by to say hello and we cut one more tune, “I’m My Own Grandpa.”

Were the sessions easy?

Yeah! The bluegrass studio mentality is that you go in and play and that’s it. They don’t like or need to do a lot of takes. Nothing we did went for more than three takes. The session with Red Allen was just four hours! I took it until Red got tired. It was a long day because we’d rehearsed.

We cut six tunes with Red. I had originally had other tenor singers in mind, Bobby Osborne or Curly Seckler—other guys from that era. Red had wanted me to use his son Harley. He said, “You gotta hear him sing.” So I decided to cut the tunes and overdub Harley. That way if I decided I wanted to use someone else I could. So Harley went in and put tenor on all three cuts each of “My Aching Heart” and “Teardrops In My Eyes” so that if I wanted to I could edit the three takes together later. He went straight through it, didn’t stop, didn’t have to redo anything. Sounded pretty good!

You performed, recorded and produced records with Red and Porter Church in the mid-1960s. What was it like to get back together with them?

It was great! A lot of fun. Nostalgia. But it was very compressed, like all the other sessions and intense. We had just a few hours. Our only regret about the sessions with Red was that we only had one day. Everybody said, “Gee I wish we had more time. We’d keep going tomorrow.”

I’d run into Red a few times in the past eight years when I’d play Dayton and he’d come down to the club. First time it was a jazz club and I got Red and Harley up on stage to play three or four bluegrass tunes. That night Red told me, “You’ll never see me again,” because he had just had heart surgery. A couple of years later I came back and he was still there and I said, “Hey man, you were wrong!” (Laughter) So when I started thinking about recording some traditional bluegrass I wanted to do it with Red and some of the guys that were my elders when I started. Red Allen and the Osborne Brothers are one of the pillars of modern bluegrass. They sort of wrote the book on a certain aspect of bluegrass that Bill Monroe didn’t create. Twenty-one years ago these guys were my teachers.

What about the next session?

The next session was Herb Pedersen and Del McCoury, another violinless session. I hadn’t played with Del in years, Herb Pedersen had never played with Del, and that was exciting. We went into the studio the night before, set up the microphones and cut one tune, “Memories Of Mother And Dad.” The next day we came in and cut eight more. That band cut the most tunes.

Was everything done live except fiddle?

Everything except some tenor singing. Herb overdubbed tenor parts so that he could concentrate on playing banjo during the choruses.

How did you first meet Del McCoury?

I saw the first show Del ever did with Bill Monroe, which he did on banjo, in 1962. He’s a damn good banjo player. It was put on at NYU by a group I was active in called Friends of Old Time Music. Bill picked up Jack Cooke to do the date with him. At the time Jack had a band in Baltimore and Del was his banjo player. I used to hang out with Ralph Rinzler and he had them staying at his house.

There’s a funny story about how Del switched from banjo to guitar. Bill Monroe hired both Bill Keith and Del McCoury on the same day to play banjo. They both checked into the same hotel room, both there with their banjo cases. That’s the reason Del became a guitar player! I guess it worked out magnificently.

I got to know Del and at some point I got an offer to play a gig in Troy, New York and got Del to do it with me. He drove all the way up from Baltimore then all the way to Troy for fifty bucks! We rehearsed in the car on the way to the gig. We had a real good time.

Doc Watson is also an old acquaintance of yours.

Yeah. Ralph Rinzler played me tapes of Doc he’d brought back from North Carolina. Ralph went down there to rediscover Clarence Ashley and Ralph just happened to hear Doc. I met Doc when Ralph brought him north to play. Doc was the first professional musician to ever invite me onto a stage to play with him. I was about sixteen years old, it was at Gerde’s Folk City and we did “In The Pines” and a couple of similar style duet tunes.

On the session I wanted to do more of that with just guitar and mandolin. We had talked about the tunes and the first one we cut, “Long Journey Home,” was done in one take.

You didn’t sing tenor on this session?

No, I didn’t feel like I was an adequate tenor singer. I figured I’d overdub different tenor singers on those tunes. That’s a way of spreading the different energy around—this tenor singer from this band could overdub on the track from that other band. There’s a lot of that type of intermingling. Ricky Skaggs, Alan O’Bryant and Curly Seckler on the tenor parts with Doc.

Was this a single day of recording?

Just three hours. We did six tunes, probably three takes at the most. It came out so well I considered that it should maybe be developed into its own album.

It’s interesting that you recorded two double mandolin tunes, “If I Lose” and “Leavin’ Home,” with the Nashville Bluegrass Band. I don’t believe I’ve ever heard a bluegrass band with two manolinists. It reminded me of your earlier David Grisman Quintet material.

It wasn’t planned. Mike Compton was at the sessions and I wanted to have him do something. As far as bluegrass goes he plays mandolin about as good as anybody I know. The first thing we did was “If I Lose”—a Jesse McReynolds style duet. “Leaving’ Home” is more of a jam, there was nothing coordinated ahead of time. As far as a precedent for double mandolins in bluegrass, there’s probably some double mandolin stuff on “Here Today” (with Pedersen, Vince Gill, Jim Buchanan and Emory Gordy on Rounder 0169). Charlie Monroe also recorded with two mandolins, so did the Country Gentlemen. I didn’t really think about it, I just wanted to include Mike. I do like to use two mandolins and it does give it a little more of that Dawg touch.

Had you considered having Curly Seckler play mandolin on the record?

I kept trying to get him too! In the studio we fooled around a little bit. He’s a real good mandolin player, real fine tremolo, always played tasty stuff, and kept a real good beat going. Definitely an unsung hero, especially when you think of how much of the Flatt & Scruggs sound he was singing. He told me about how when the Dobro came in (with Flatt & Scruggs) “they took all my solos away.” Buck Graves came in and that was the end of his lead mandolin playing.

I’d never met Curly before the sessions though I’d admired his singing and playing with Flatt & Scruggs. He’d also done some singing with Red Allen. The first time I spoke to him by phone we talked for about twenty minutes. The next time it was about twice that. Finally we were talking for hours. He’d tell stories about Charlie and Bill Monroe, this and that. It was fascinating and I would even take little notes as he was talking. He has an interesting insight into bluegrass because when the Monroe Brothers broke up, Charlie hired Curly to play mandolin and called the group Monroe’s Boys. Then when Flatt & Scruggs left Bill Monroe, Curly played mandolin with them. He’s always been in Bill Monroe’s shadow.

The final session was in Nashville?

Yes, with a lot of great fiddlers, Mark O’Connor, Ricky Skaggs, Jim Buchanan and Sam Bush! We tried to work around everybody’s busy schedule.

The double fiddle sound is quite prevalent throughout the album.

Double and triple fiddles. I’ve always liked that sound. It satisfies my need for orchestration. Originally, I had intended to get two fiddlers together at once but Bobby Hicks convinced me to use one person to do both parts. That’s what we did and it really came out nice.

Your own bluegrass mandolin playing from the mid-1960s (“Early Dawg” Sugar Hill 3713) is wilder and more bluesy than most of your playing on this album.

You mean all those A major tunes that I play in A minor. I think that’s the Frank Wakefield influence, you’ve heard his record of “Little Birdie.” I do that some on “Pretty Polly.” I was trying to be more traditional on this record, but I did have a few lapses.

How much did you practice this material before the sessions?

I didn’t really do any, cross my heart! I rehearsed a little bit with the bands before each session, but that’s it. Technically I don’t think bluegrass is any harder than the music I’m trying to do. It’s mostly a case of keeping your head into bluegrass. I always listen to a lot of it, pure stuff—Flatt & Scruggs radio shows from 1953 and ’54, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Bill Monroe records, Stanley Brothers records. That keeps my head in bluegrass so that when I go into the traditional mode it’s familiar. What to play is a stylistic decision.

If you study a style the way that I’ve studied bluegrass, you don’t lose it. It’s like an artist who learns to draw and goes on to painting, he could probably still draw pretty well.

Bluegrass is a discipline. I had an opportunity to study it with people who really knew it, like Red Allen. Now it gets down to remembering what I used to do along with the added advantage of having developed my mandolin playing. In other words I can play those bluegrass runs better now even though I don’t practice them, though I do sometimes throw in bluegrass licks when I’m playing jazz.

How do you relate the traditional music on “Home Is Where The Heart Is” to the jazz flavored music you usually play? Is it all the same to you?

No, this is all vocal music and that’s all instrumental. This is all written by somebody else; Dawg Music is, by and large, written by me. I keep them separate.

If you’re an actor it’s like saying “How do you separate playing Shakespeare from playing slapstick comedy?” I think musicians should be capable of playing different kinds of music. Bluegrass is playing the music of Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers and Jimmy Martin. I’ve had an education in that and it’s something else I can do. With this project I’m taking a role in a style of music that I’ve done before.

You mention studying bluegrass in your early years, sort of “on-the-job” training with Red Allen. How did you end up playing in his band?

I’d known him since I’d produced a record “Red Allen, Frank Wakefield And The Kentuckians,” Folkways FA 2408) with him and Frank Wakefield. He called me up one morning and asked me to play with him. I was in college at NYU and it was ’65 or ’66. I played with him on weekends during the school year. We did shows with Flatt & Scruggs and Jim & Jesse but bluegrass didn’t have the respect that it has now. There were no bluegrass festivals, per se, they were just show dates. But it was great for me because that’s what I wanted to do.

The only thing I didn’t like about it was that those guys never wanted to play. I mean, they never played except on the gig. I couldn’t understand it! I always wanted to pick.

But you haven’t played bluegrass until you’ve slept in a hotel room between Red Allen and Bobby Diamond. He’d only get one room and there’d be five guys sleeping in it. I was so into the music that I didn’t even notice. I remember we got locked out of a room once and they lowered me in through the bathroom window. It was a good time because I dug the music so much.

Was it difficult being a city boy among country boys?

Well, I dug those cultural differences. It was grits and country ham. I was always a non-conformist and this was about as different as you could get in the early sixties. Also, I thought it was fantastic music. It seemed to come from a different place and time and it rang true. People in the city didn’t have that lick, that authentic sound. Getting to play with Red allowed me to sound more authentic. When you listen to a Stanley Brothers record it’s just got that sound . . . there’s no way you can learn to do that.

How did you learn to do it?

I learned a certain aspect of mandolin playing which I learned by participating. Enough of it rubbed off.

Did Red give you specific tips?

He gave me a lot of tips, mostly about part singing and phrasing. It was like folk medicine. These guys don’t technically say very much but they’ll say “Play the song.” Even on this session some of that happened. We were doing “Love Come Home,” which didn’t end up on the album. I got this idea to start it with just the banjo solo on the melody. Then on that A chord, the seven chord in the key of B, the whole band would come in. On one take Porter would kick it off and all of a sudden he stopped and said, (serious voice) “I’m sorry, I didn’t play the song.” In other words, these guys have a real strict idea of how they want to play the melody. That’s very important to bluegrass musicians to play the melody and play it right.

One of the first things I noticed about the new album is that you include a lot of pre-bluegrass, more old- time material like “Willow Garden,” “[Have A] Feast Here Tonight,” “Foggy Mountain Top,” “Little Willie” and Charlie Poole’s “Leavin’ Home.” I expected more modern bluegrass.

One of the things that always attracted me to bluegrass and all that other music, was the authentic vibe, the traditional roots of the folk songs. That kind of music is deep, it’s survived for hundreds of years because it has some kind of universal application. It relates from an earlier time, it comes from another world. It’s, in a sense, a fantasy. Take “Pretty Polly,” I don’t know when that murder was supposed to have taken place or if it in fact did, but it’s like reading Robert Louis Stevenson. It’s part of a tradition. I wanted a lot of that on this record.

This project reminds me of the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken”album (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band-United Artists 1198).

I hope it sells that well! It encourages me on a commercial level that something like that could succeed. I think this will have a different effect though. It (“Circle”) got beyond bluegrass. This is more musically unified. I also tried to have the players not do their greatest hits. There’s some of that included but I tried to get them to do something else than they normally do. On that record (“Circle”) everybody sort of did what was already on their own records.

You’re famous for the great instrumental and vocal sounds on your records. How do you achieve it?

A certain amount of it is the engineer. Craig Miller (Grisman’s manager) helped out a lot on this, especially with working in different studios. I just try to keep on top of the basic things, good players, instruments, mikes and other equipment. You do a little research. You don’t go to the first studio in the phone book. There always are problems and things that you strive for that you don’t attain. But in striving you probably accomplish something that’s better than normal.

The key is to get Del McCoury, Bobby Hicks, Herb Pedersen, Curly Seckler and the rest of them. Those guys just sound good. With J.D. Crowe it’s not just a banjo that you’re recording. Ricky Skaggs, you listen to that voice on a good microphone and you’re going to hear a sound that’s larger than life. Same with Red Allen.

And, a lot of it is experience. I picked up some things along the way and remembered them, not that I know so much, but experience will teach you certain things. Mistakes were made, but fortunately they weren’t critical mistakes. I had great success at getting good sound at Bayview Studio and that set the standard for other places to live up to. And, I mixed it all there. I’ve been more successful in mixing at the studio than at any other. It takes me less time there. In the past, like with “Acousticity,” (Zebra ZEA 6153), I had to remix things three or four times, of course it was more complicated.

I once heard you referred to as “King Splice” by one of your early quintet members. You use the available technology. You like to cut tape.

I don’t like to cut tape, but I do like to have that option. I save everything I record and it gives me a certain flexibility. Generally throughout this record there are complete takes. I tend to forget about those edits I did make because I can’t hear them. That’s the whole point, if you can hear it, it’s a bad edit.

On one take of “Close By” Del McCoury broke a string during my mandolin solo. He sort of stopped playing but the band went on. I really wanted to keep that take up through the mandolin solo because it was the best. Unfortunately, the guitar track was messed up where he broke the string. So we did some other takes from that point to the end of the tune and cut them together into a complete take. But there was still this string break behind my solo. So I took a section of that song, just Del’s rhythm guitar playing and bounced it onto a separate two track machine. Then I synced it back onto an empty track on the multi-track machine behind the original mandolin solo with the string break. It was a matter of hitting play on the two track while the multi-track was recording to get it synced up. It was hit or miss, wild sync, but after awhile it worked.

So when you mixed it you pulled out the broken string track and substituted the corrected track.

Right.

You sing quite a bit on this record. How do you relate to your singing?

I don’t really consider myself a good lead singer. I can sing baritone but that’s more of a blending, group participation thing.

Singing a song is like a dramatic role that I have difficulty playing and I just don’t particularly like the sound of my own voice. I do like to try to sing harmony though, especially with great singers.

What are you most satisfied with about this project?

It was all fun, like something I get to do as a bonus. My record company is not interested in the bluegrass side of what I can do, yet they’re nice enough to let me do it elsewhere. I get to do an extra record, every few years, of music that I really dig playing but don’t do everyday.

Will you be doing any bluegrass shows?

I’d like to, but there has to be a demand for it. I’d like to take a band out. Actually my next gig is as a special guest with the Nashville Bluegrass Band. I’d love to do more things like that but I guess the demand has to come before the supply. I’ve thought of recruiting some young guys but people would probably want to hear the players on the record. This album was sort of a pleasant side trip for me, but my Dawg music is still the main thing. Bluegrass sure feels good though!