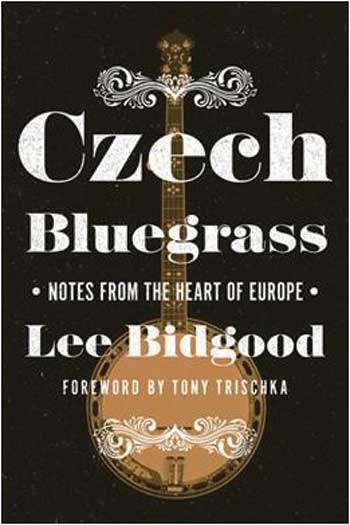

CZECH BLUEGRASS: NOTES FROM THE HEART OF EUROPE

CZECH BLUEGRASS: NOTES FROM THE HEART OF EUROPE

CZECH BLUEGRASS: NOTES FROM THE HEART OF EUROPE

BY LEE BIDGOOD

Univ. of Ill. Press 9780252083006. Foreword by Tony Trischka, paperback, b&w photos, 192 pp., $24.95. (Univ. of Ill. Press, 11030 S. Langley Ave., Chicago, IL 60628, press.uillinois.edu.)

If you’re reading this in America, you certainly know about the great bluegrass that’s sprouted up around the world, especially in Britain, France, Italy, and Japan. But don’t forget the Czech Republic (part of the former Czechoslovakia). Lee Bidgood chronicles and celebrates these Eastern European sounds in this landmark—and long overdue—history.

The term “notes” in the title is fitting. Bidgood is an associate professor of bluegrass, old-time, and country music in the Department of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University. So, not surprisingly, his book is often a very scholarly study. But it’s enlivened by his personal notes about the musicians and culture that have embraced America’s Southern sounds. Thanks to his first-person experiences playing fiddle and mandolin in Eastern Europe, the book is filled with happy anecdotes, as well as the insights and opinions of Czech players and luthiers.

So, if you find the opening chapter “Place, Meaning, Community and In-Betweenness” to be a bit on the academic side, dive right into the next, the fascinating “Histories and Backgrounds.” The Czech people have a vibrant, centuries-old folk music tradition, but there were also notable historical and cultural influences that created fertile soil for the transplanting of bluegrass and old-time. For example, like many other Europeans, the Czechs were fascinated by books and movies about cowboys; the Old West often merged with the South in the collective imagination. They also had a venerable tradition of “tramping”—hiking in nature, wandering the roads, and camping carefree along the way—that made them receptive to bluegrass and old-time music’s freeborn, life-in-the-country spirit. Indeed, by the early twentieth century, there had grown a special genre of folk music called “trampská písen” or “tramp songs.”

After World War II, American popular music, including country, got a big boost in Eastern Europe when Armed Forces Radio and Voice of America broadcasts were heard behind the Iron Curtain borders of the Soviet Bloc, including Czechoslovakia. The resourcefulness of fans living in then-Communist countries is inspirational; how they purchased smuggled American records, tapes, and music books (notably banjo instruction manuals by Pete Seeger and Earl Scruggs) on the black market, then laboriously copied and circulated these precious resources (even to the point of making primitive copy records using castoff x-ray film sheets as vinyl substitutes). When some fans were discovered by the authorities to be listening to folk or country, they avoided punishment by cleverly pleading that this was music of “the oppressed American working class.”

American musicians eventually visited Czechoslovakia as part of cultural exchanges. Their shows were heavily attended and landmark events, notably Pete Seeger’s 1964 concert in the capital city of Prague and mid-1980s tours by Tony Trischka & Skyline. American bluegrass and old-time fully blossomed after 1989 as the Communism system finally ended. Since then, bands such as Druhá Tráva have found success and even name recognition in the West.

Trischka, who has returned often to the Czech Republic where he’s a banjo superstar, was the perfect choice to write the book’s engaging forward. He shares his moving personal experiences with local musicians and fans and states convincingly, “Of the many countries that have caught the bluegrass bug…the Czech immersion in bluegrass has had the deepest roots and has been the longest lasting.”

Lee Bidgood frequently inserts himself in the book’s narrative, but very successfully and without the usual look-at-me pitfalls of this approach. In the chapter “Making Bluegrass,” he does an outstanding job of segueing from his experiences into chronicling a multitude of leading musicians and luthiers—their stories and outlooks. The tales of how many came to the music in the first place will be familiar to anyone, from Yankees to Japanese, who’s undergone the trial-and-error, labor-of-love process of learning far from the source. Bidgood’s concluding lists of recommended recordings, films, and videos—plus his cited book and article sources—are definitely worth browsing.

Also, let’s never forget that bluegrass and acoustic music in general owe a huge debt to the Czechoslovakian world. It was three brothers—John, Emil, and Rudy Dopyera—who, in the 1920s, perfected the resonator guitar. In selecting a name for their instrument manufacturing company, they made a marvelous play on “Dopyera Brothers” plus a word that means “good” in both the Czech and Slovak languages—Dobro.RDS