Home > Articles > The Archives > Confessions of a Bluegrass Musician from New York

Confessions of a Bluegrass Musician from New York

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1977, Volume 11, Number 11

Northern Bluegrass — A Tangle of Roots and Contradictions

The whole idea of Northern bluegrass sounds like a contradiction in terms. Bluegrass is the essence of the rural music of the traditional South. It seems impossible that Northerners, especially those from city and college backgrounds, could make bluegrass their music. It probably is impossible.

But what do you call it when a 14-year- old kid in the Bronx happens to hear a record by Flatt and Scruggs and then proceeds to devote himself to learning to make that sound, never having taken up any other music seriously? What if over a period of years he finds his musical and personal identity somehow tied up in bluegrass (still never having been south of Washington D.C.), finds others like him, and they start to play their favorite music together? Answer:

Possible or impossible, Northern bluegrass exists. Sure it’s filled with contradictions and uncertainties, but whatever it is, it has been evolving—in New York State, at least—for about 20 years. By the middle 70’s six bands from New York State had worked long and hard enough to achieve unique musical identities, put them on records, and travel to bluegrass festivals far South to show what they could do. By 1976, all six had either broken up or left the state, but others will inevitably step in to deal with the same contradictions.

It all started with the “folk boom” of the late 50’s and early 60’s. Actually, it wasn’t really a boom, but at that time a certain amount of good folk music was recorded and the records started getting around. They found their way to college dorms and radio stations, were borrowed and taped, and they hooked a few unsuspecting souls along the way.

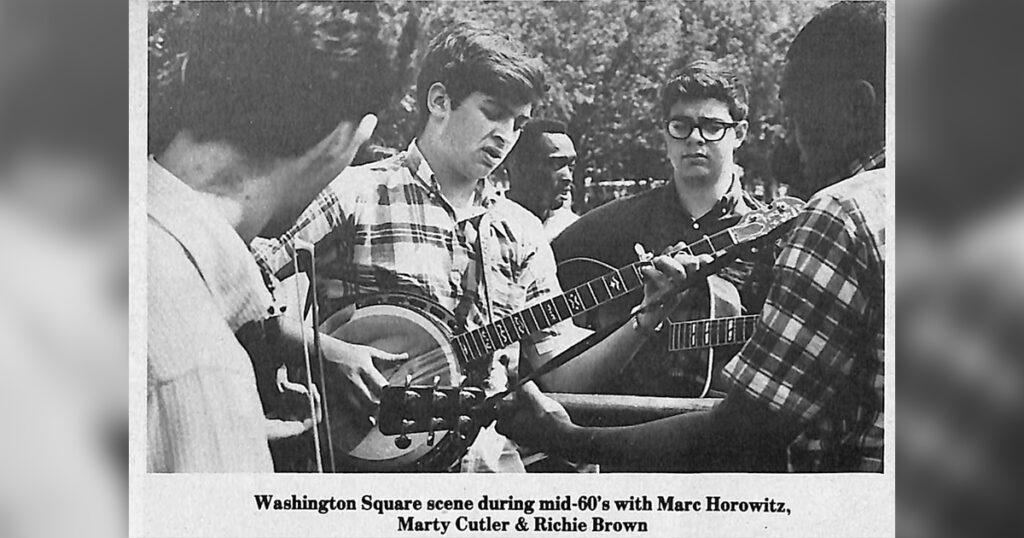

In New York City around 1960 (I was that 14 year-old), the opportunities to hear bluegrass were rare indeed. Only a few LP’s (and no singles) could be found in the racks in record stores, and perhaps one known group came to town in any year (Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley, Jim and Jesse, Bill Monroe). The people, who had started learning from their records a few years before I did were the pickers I heard most. On Sundays when the weather was good they would congregate in Washington Square Park in downtown Manhattan. There we would have a typical “parking lot” scene, picking, singing, and competing with one another until 6 pm, when friendly policemen would break in to enforce the local music curfew.

One of the groups that formed from the Washington Square gatherings was the Greenbriar Boys. They became polished and entertaining enough to find a place in the folk boom, playing folk concerts (including TV’s Hootenanny), making records for Vanguard (one with Joan Baez), and inspiring many others in the process. They, along with the Charles River Valley Boys (from Boston), the Kentucky Colonels (southern California), Keith and Rooney (Boston), and the Dillards (Missouri), provided us young city slickers with some bluegrass heroes who were something like ourselves. They weren’t quite “the real thing”, but they had our rapt attention and they influenced us.

One thing these younger groups shared was hot picking. Banjo was featured most, and unlike most of the older groups, the guitar was often a featured lead voice. Fiddle, the standby of traditional country music, was for some reason usually absent (except on records, where Southern fiddlers such as Tex Logan, Herb Hooven, Buddy Pendleton, and Jimmy Buchanan would be called in).

This was the “tradition” we Northern bluegrassers grew up with—definitely different from what Bill Monroe grew up with, but still related. Being distant from those Southern roots, we hungered for them all the more. The whole Washington Square gang was there on the edge of their seats when Monroe first came to town to play at the NYU law school auditorium (how different from the school auditoriums he had played throughout the South). Several of the most respected of the city musicians took great pains to collect the best of the early bluegrass 78’s, and preached the gospel to the uninitiated. Some were as orthodox and traditional in their music as any 55-year-old Kentucky farmer. The rest of us hung in limbo, loving and respecting the traditional sound, but also inclined in other directions—hot picking, performing for “folk” audiences (who invariably found bluegrass the most exciting part of the program), trying to put a little of ourselves into the songs, rather than parroting the unfamiliar accents and subject matter of traditional bluegrass.

This leads to the big issue: What does a Northern bluegrass group do about songs and singing? Can a white man sing the blues?

Sure a Jewish kid from the Bronx can kick off a solid instrumental break to “Blue Ridge Cabin Home” or “I Saw the Light”, but can he sing it with any conviction? Answer: Of course not, but there’s no alternative, so he’ll try anyway. After a while he may gravitate toward less alien territory. It is possible to find songs not centered on the South, cabin homes, and country graveyards: “On and On,” “Eating Out of Your Hand,” “Fox on the Run”….

Or he may relish the alien aspect of bluegrass and go overboard being hokey or maudlin to the delight of urban-sophisticate friends and audiences. After all, a group with a name such as Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys seems funny to city people. That kind of attitude is easy to slip into, but it doesn’t square well with the true deep-down feeling for bluegrass music that was the original inspiration. Condescension and respect don’t often mix, but then, Northern bluegrass is filled with exceptions.

Another thing about Northerners and bluegrass singing: On the whole, Northerners don’t have the relationship with singing that Southerners do. They don’t usually have a tradition of family and church singing, and they tend to be more self-conscious and stylized than free and direct in their vocals. That works for jazz and pop, but not bluegrass. Cutting loose with a high lonesome sound is definitely “deviant behavior” among Northerners, which may be why few ever try.

In short, the dilemma of Northerners and bluegrass singing: Not being in close touch with the material most basic to bluegrass, and not developing the vocal intensity needed to make singing the focal point of the music.

A common response is to get more deeply into the instrumentation, and that has been a rich musical lode in Northern bluegrass. Starting in 1959 with the Greenbriar Boys, New Yorkers have frequently won top honors at Union Grove. Throughout the 60’s various aggregations, always called the New York Ramblers, would make the 1500-mile round trip and come back with cups and ribbons. But it was always for the picking, not the singing.

The Saga of Country Cooking, Northern Bluegrass Band

With the 70’s came a new climate for bluegrass in the North. The new vitality of bluegrass, sparked by the growth of festivals, had spread it further than ever before. It was now regularly surfacing in places where many people would hear it—popular movies like Bonnie and Clyde and Deliverance, records and performances of popular rock groups (Grateful Dead, the Byrds, New Riders of the Purple Sage, Seatrain) whose members had played bluegrass before taking up electric music, and who now wanted to bring their early influences back into their music. “Country-rock” caught on and under its banner, many people heard Bill Monroe songs and Scruggs style banjo for the first time.

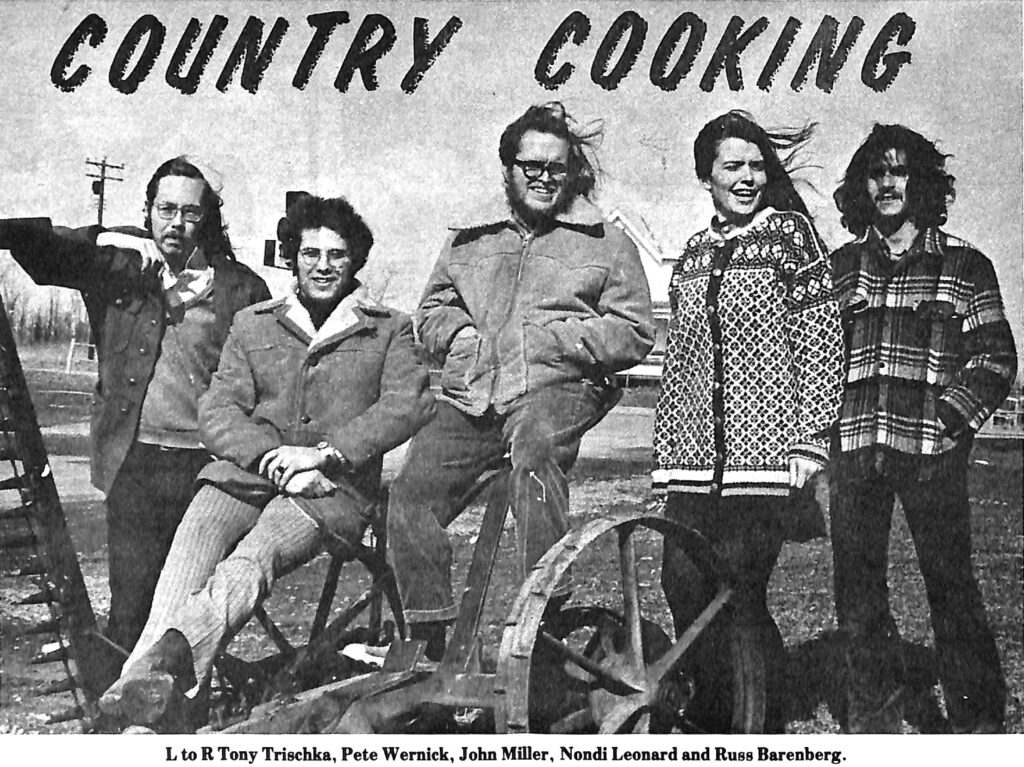

By now I had moved upstate from New York City to Ithaca, a college town nestled in the hills of the Finger Lakes region. Bluegrass musicians weren’t exactly growing on trees, but there were enough around to start Country Cooking. Our first year together was very informal, like the other groups I had been in. We played at Cornell University folk-type events and at a few local bars, mostly for fun. But after a while, the audiences started to grow—probably in part thanks to the growing interest in country-rock. (All too often, in fact, people’s requests would not be for bluegrass songs, but for “anything by the Dead or the New Riders”. Or more simply, people would just yell “New Riders!” or “Eagles!”).

Given the chance to play at the Salty Dog, a local rock ‘n roll bar, we surprised the management by drawing good-sized crowds, who came in and danced up a storm. But our success there waned as the bartender ruefully noted that “All your people drink is orange juice or water.” He was exaggerating but it was true we weren’t drawing the drinking crowd the way groups like Raw Meat and Slippery Hips did. Our crowd was more funky “back to the soil” types who liked us for our acoustic string band sound. They do-a-dosed, swung partners, made circles, clogged and whirled around, creating a spontaneous alternative to cliche’ rock ‘n roll dancing. This kind of dancing became almost a trademark for us, and we would regularly be hired for outdoor weddings and square dances where the same mood would be generated. As other bluegrass and old-time string bands formed and started playing around, the scene would be repeated. In short, a sort of local cultural tradition came together where acoustic string music and the dancing it inspired brought people together for many happy times—probably something like the ones that Uncle Pen and Bill Monroe played at, decades ago in Kentucky.

Music means more when it’s part of a living culture than when it’s a collection of techniques learned from records or printed pages. Shaped by the audience and the circumstances it grows out of, it develops its own special character. We responded to our audience by giving them more of what they wanted: good-timey, good-humored danceable music. More Jimmy Martin-type novelty songs, instrumentals, and fewer slow and serious numbers. We made little effort to be “strictly bluegrass” but called on contemporary pop music, ragtime, blues, and whatever material and instrumental ideas we thought would fit us and our audience.

This growing audience became more and more a factor in our individual lives. Before Country Cooking we were all members of bands that never played much for money. But now we were able to ask a good price for our services. In the Spring of 1971 we made a simply-recorded instrumental record for the fledgling Rounder label, and within about a year it was helping our popularity. Suddenly we discovered a new opportunity for well-paid work: college concerts. I took it upon myself to find out who were the concert chairmen at colleges all over the state and to call them persistently to get gigs for us. These young go-getters had ample budgets from student fees, and had to spend it all during the school year (or risk the possibility of getting less to spend the following year). There were regular opportunities for groups like ours to be opening act for featured folk or country-rock performers (Scruggs, New Riders, Commander Cody), and the money was good-often $500 or more for just one set. Not to mention the thrill of entertaining a large attentive college concert audience through a good sound system. Or sometimes we would drive a few hours to a Friday beer blast at some remote upstate college, and take home a goodly paycheck.

We were now making almost enough to live on, with the possibility of becoming self-supporting. That position was a bit strange—we hadn’t really expected to become professional musicians, and the music we were making, while enjoyable, didn’t hold much deep meaning for us. But the availability of money for entertaining college students, and the distant prospect of recognition of our music through records was strong temptation.

In 1972 we recorded enough music for another record with the help of some good pickers not in our performing band. We had all been writing tunes, and put a lot of energy into the recording. I thought that with the popularity of “Dueling Banjos” at the time, there might be an opening in the commercial market for our driving, somewhat rock-influenced sound. So I took the tape down to New York City—the Big Apple—and visited the 30th floor offices of RCA, Warner Brothers, Elektra, Epic, Mercury, et al. Maybe half of them actually listened to the tape, and some made encouraging sounds like, “We truly enjoyed Country Cooking and hope that the Coast loves it.” (letter from Mary Martin, Director A & R, Warner Bros.)

But after several months of waiting for word the only thing concrete we had were letters saying, “While the individual people at Epic and Columbia loved it for what it is and appreciated the music a whole lot, it’s the predictable story of ‘although the band really cooks, we won’t be able to market it in big volume’ or thoughts to that effect.” (Tom Werman, Asst. Director A & R, Epic) and, “Passing on Country Cooking was a very difficult decision for us to make because you are excellent musicians and extremely versatile in your genre. The problem is finding a market for you in pop music today. Personally, Country Cooking is a band I would listen to at home, were they on record.” (Barbara Bothwell, Manager, Talent Development, RCA).

This experience helped us learn our limits, as did the results of a similar effort trying to interest New York talent agencies in taking our case to concert promoters. As I was told by a college friend who had gone on to manage Sha-Na-Na and several other popular rock bands, “You’re good, but to market you to a pop audience I would have to go on a crusade, and I’m not looking to do that.”

The band continued for another year with some personnel changes and almost-a-living commercial success. The eagerly-anticipated second record finally came out on Rounder. In mid-1974 we went into hibernation as Russ Barenberg and John Miller, two of the original members, left the band to devote more time to other kinds of music, especially jazz. Unfortunately, their new efforts had even less commercial appeal than bluegrass, and both continued to need livelihoods outside of playing music.

In late 1974 Country Cooking was revived with the arrival of some eager new members who came to sing. Howie Tarnower and Alan Senauke, the Fiction Brothers of New York, both moved to Ithaca from San Francisco to pursue their powerful bluegrass singing in a context where they might find critical acclaim and an income. The new Country Cooking wanted to sound like authentic bluegrass, to take its music seriously as personal expression—on a level deeper than foot-stomping. Though we tried not to discourage such enthusiasm, the traditional-type songs and delivery seemed to work against us—except in front of folk-type audiences. It’s hard to dance to words and sounds of loneliness and trouble and we didn’t do as well at the Salty Dog as when “Sophronie” and the “Battle of New Orleans” were our standbys. Our hard work at exploring our own souls within a traditional bluegrass sound was musically satisfying, but just not as successful as hot picking, comedy and foot-stomping. Our limited success was not enough to hold us together and by late 1975, after recording an album for Flying Fish, Country Cooking was finally defunct.

In the five years since we had started, ground had been broken. Bottle Hill (Albany area), the Buffalo Gals (Syracuse), and Breakfast Special (New York City) had formed and developed both local and out-of-state followings through novel approaches to bluegrass and other music. Unable to register strongly either as bluegrass or as pop groups, Breakfast Special has broken up and the Buffalo Gals and Bottle Hill have relocated in Nashville and New Jersey respectively, hoping to find more fertile dirt. Now it’s up to them and others to carry on the eclectic tradition of New York State bluegrass.

Reflection Section, on Middlemen, Day Jobs and Music

The music business is really the entertainment business, with everything measured by how much money how many people pay to see or hear you. To offset expenses for travel, phone calls, publicity and sound equipment with money left over to provide a living for five people is a tall order, it requires some kind of mass audience. So the main channel to making a living is through succesful selling to the middlemen (record companies, agents, promoters) who have almost complete access to the means of producing commercial success. But as the record company exec said “The problem is finding a market for you in pop music today.” The middlemen deal with music in terms of a few tried and tested categories: top 40, progressive rock, MOR (middle of the road), country, soul, and jazz. It was clear that bluegrass was not established as enough of a “market” for major companies to bother with. Like so many other bluegrass bands, we couldn’t afford to give up our day jobs.

On one hand, day jobs keep musicians from developing their music fully. There’s less time to practice, both individually and together. Overall concentration on musical development is diluted. But being a full-time professional musician also has its limitations: road work, constant scuffling during lean periods, and above all the constant pressure to succeed not just as music but as entertainment (which, you’re always reminded, is really what you’re selling), are also major distractions from the ideal of fulfilling your musical destiny. The distractions can take a lot of the fun out of music, the very thing that brought you into it in the beginning. At one point I was disturbed to realize that I was spending more time with the telephone than I was with my banjo. It was not a case of the end justifying the means, but the means distorting the end.

Being a full-time musician does give the time and incentive to develop your music. But it can also lead you to compromise your music, and it can be a strain, plain and simple. However each person makes the choice, it’s good to know that fine music is not the exclusive province of those who make money at it. Ancient wisdom says “If the shoe fits, wear it”, “Small strokes fell great oaks”, and “Strike while the iron is hot”. Somewhere in there lies the proper attitude toward playing bluegrass music and most of life’s other challenges.