Home > Articles > The Archives > Cliff Waldron—Back in the Bluegrass

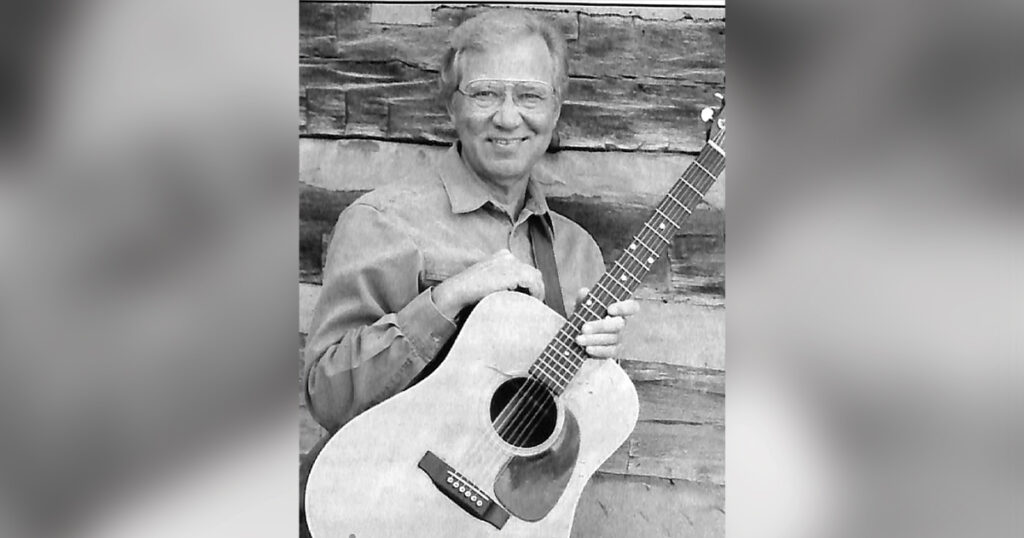

Cliff Waldron—Back in the Bluegrass

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1997, Volume 32, Number 4

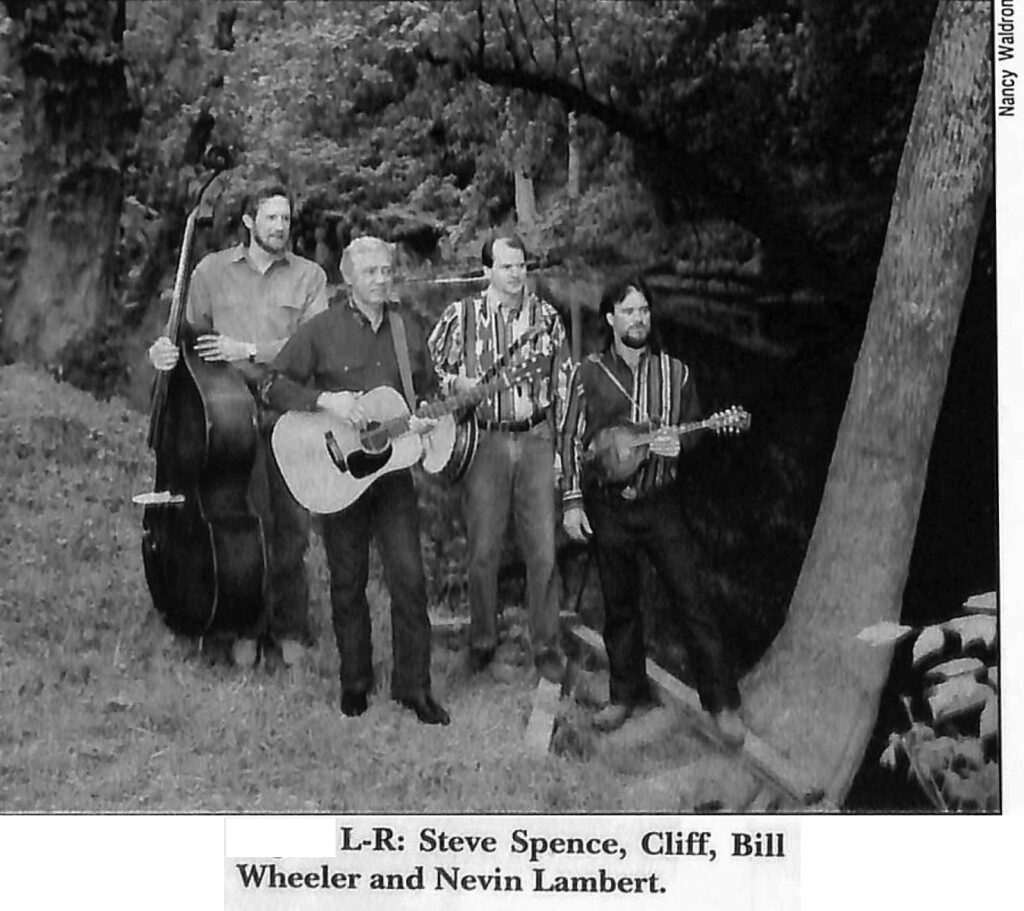

After nearly 25 years away from bluegrass, Cliff Waldron has reformed his band. The band features former New Shades of Grass banjoist, Bill Wheeler, and new members Nevin Lambert and Steve Spence on mandolin and bass respectively. The band is playing the same kind of driving, intense bluegrass which brought Cliff acclaim in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Cliff Waldron, a native of Jolo, W.Va., and began playing at about age 12. He moved to northern Virginia, in 1962, and from 1964-1966, played locally with the Page Valley Boys.

Cliff s professional career began in 1967 when he and Bill Emerson joined forces with Wayne Yates and Earl Brown. This was the first edition of a group which would make a major impact by introducing songs from outside bluegrass to bluegrass audiences.

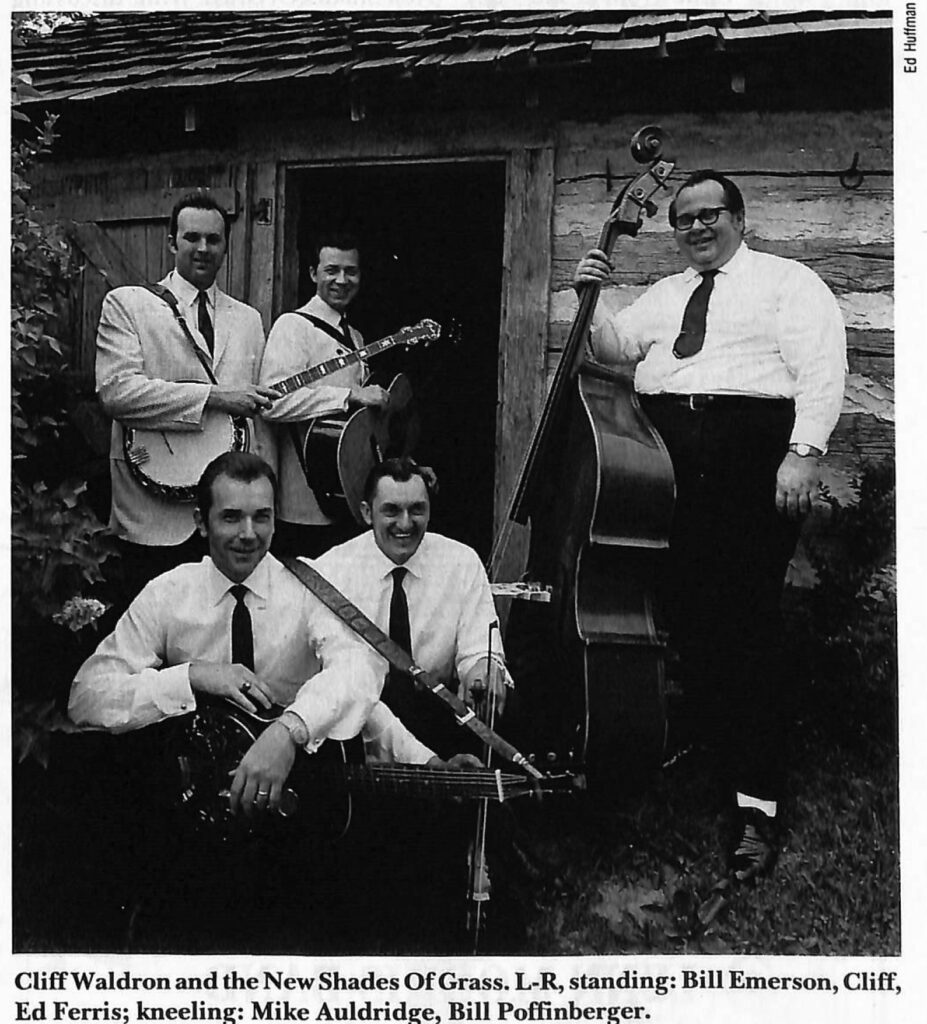

The late ’60s were a period of growth in bluegrass, and Emerson and Waldron were at the front of the “contemporary” pack. Their first album for Rebel, featured an all-star supporting cast which included John Duffey and Ed Ferris. By the time their second album was recorded, the band was set with Bill Poffinberger on fiddle, Mike Auldridge on resonator guitar, and Ferris on bass. This core group recorded a third LP, [and was’ working on a fourth] when Emerson left to replace Eddie Adcock with the Country Gentlemen.

Unsure about running a band, Cliff disbanded the group for about a year and played with the Roanoke, Va.- based Shenandoah Cutups. Just short of a move to the Roanoke area, Cliff reassembled his own band. The Cutups played a much less “adventurous” type of bluegrass than Cliff was used to. So after deciding to stay up north, he called together Mike and Dave Auldridge, Bill Poffinberger and Ed Ferris, and with the addition of Ben Eldridge on banjo formed the New Shades Of Grass. For the next six years and seven albums, the New Shades Of Grass pleased audiences from Maine to Florida and Virginia to Oklahoma. The band was a proving ground for a number of young musicians as well: Jimmy Arnold, Gene Johnson, and Larry Stephenson to name a few.

In October 1974, Cliff went to work for the National Park Service. “I reached the point in my life where I wanted to build some security, and the job at the Park Service was serious, so I took it seriously.” In December of that year, he quit playing bluegrass to settle down and have a home life.

“In January 1975, I accepted Jesus Christ as my Savior,” says Cliff. “After that, I changed my life and started being active in church, I still am.” In 1978, Cliff put together a gospel bluegrass band, with Bill Wheeler, Larry Stephenson, and Arthur Penn. The band played festivals, concert dates, and recorded two albums for Rebel but his work schedule made even regional touring difficult.

In 1985 Cliff experienced severe health problems. He had been a diabetic for many years, and suffered a complete shutdown of his kidneys, which meant dialysis treatments three times a week. In 1986, a kidney transplant started him on the road to recovery. He still needs to watch his diet and medication, but he is feeling good, and is doing well.

In the fall of 1996, Cliff retired from the Park Service. With a long list of things to do in his retirement, playing music “was weighing heavy on my mind” Cliff says. “I didn’t know how much playing I wanted to do, or how hard it would to be to do it. That was the main question.”

With this in mind, he contacted Bill Wheeler to discuss possibilities and opportunities. “Billy was the first one I called when I decided to get back into bluegrass. He is a player well versed in bluegrass, and is extremely adept at providing the kind of banjo playing I want in a given song.” Cliff went to Bill’s home-studio and the two of them began working on the material for a new recording and discussing who to get to fill out the band.

Bill recalls “I saw Cliffs band at Ruby’s Restaurant in Woodbridge, Va., in 1973. The following year, I worked with Cliff for the first time. Since then we’ve played bluegrass, gospel bluegrass, and gospel country music, and recorded six or seven albums together.”

At Bill’s suggestion, Cliff contacted Steve Spence about playing in the new band. Steve and Bill had known each other since junior high school. Steve had played banjo in a couple of bands in the ’70s but had retired from playing music to concentrate on raising a family and his career. In 1992, at a local jam session, due to the abundance of banjo players, Steve began playing bass, and had worked with Bill a couple of times. Steve is the Editor of Acoustic Musician magazine.

During the initial conversation with Cliff, Steve mentioned Nevin Lambert, a mandolin player and tenor singer he knew, who had worked with Bill in the band of Leon Morris. Nevin played in the mid-Atlantic region through the ’80s, and quit playing because he relocated to Dayton, Va., and had not played seriously for about five years.

The four got together at Lambert’s house in the winter of ‘96 to see how it would sound. Although there seemed to be some potential, Cliff was concerned about how long it might take to “get things together.”

Content in their retirement from bluegrass, Spence and Lambert agree, an opportunity to play with Cliff Waldron was too good to pass up. Lambert says, “Playing with these particular guys, and the calibre of musicians they are, makes playing professionally again, more exciting than ever.”

With regular rehearsals and a high level of dedication, the sound of this band compares quite favorably to Cliffs earlier work. Of his new band, Cliff says, “I was looking for people who were serious about playing, and who are willing to work to get it right. I really appreciate how hard these guys are working.”

After climbing to some pretty lofty musical heights, Cliff is now looking to reach even higher, by using the same kind of approach he used so successfully in his earlier career. “I still like to find songs [outside of bluegrass] and rearrange them, make them fit my style. Keep it fairly simple, give it a good drivin’ bluegrass sound.” Since his days with Bill Emerson, Cliff has found material in a wide variety of sources. Many of the songs from diverse places have become his most memorable recordings.

The best example is “Fox On The Run,” which came from a late ’60s recording by the Manfred Mann Band. Boosted by a number of subsequent cover-versions, this song has gone down in the annals of bluegrass history as one of the greatest hits.

Rebel Records plans to reissue a collection of Cliff s earlier work later this year. There will be two compact disc packages; a compilation of material from the three Emerson & Waldron albums, and a later release will feature material from Cliff Waldron and the New Shades Of Grass. While discussing the reissue details, the possibility of a new recording was mentioned. Cliff took a tape of some of the new songs he had been working on to Dave Freeman at Rebel, and the next Cliff Waldron project (due out in October) was underway. Even before Rebel had expressed an interest in a new project, Cliff had found eight songs, and he and Bill got together to work on them. Cliff explains, “Over a three month period, I went to Billy’s four or five times. We’d play the song, make changes, put in on tape, and do it different ways until we settled on a basic arrangement. Billy would have an idea, I’d have an idea, and we’d work it out.

“When I’m looking for material, I listen to a lot of different kinds of music; country, rock, and others. I’m listening for something that sounds different from what somebody else would do,” Cliff says. His music has always been bluegrass, even the rock songs sounded like bluegrass. “Some groups did rock n’roll songs, but they sounded like rock songs done on bluegrass instruments.” Two of the songs recorded for the new CD are from Rod Stewart and Phil Collins. “What I want to do is take the rock’n’roll song and make it sound bluegrass” Cliff comments. “When I heard the Rod Stewart song, I could just hear a banjo kickoff on that thing, and Billy plays it just like I heard it in my head.”

Cliff is, and has always been, a fan of the Stanley Brothers and Flatt and Scruggs. Playing their music is not much of a way to build a career, even though it’s great fun and a good exercise in classic technique. He likes to find old songs, but wants to do something in the arrangement to make him more able to identify with the song. The new project includes material from the McReynolds Brothers, the Stanley Brothers, and the Louvin Brothers. The Southern gospel mine was also tapped for a couple of fine nuggets. “A lot of southern gospel songs make really great bluegrass” Cliff remarks.

When our interview took place, the new project was still in the rehearsal stages, and recording was much on Cliffs mind. The recording process is one of Cliff s favorite musical activities. “You can’t get that kind of sound any other place. In the studio you can sound better than you will anywhere else. I would do that all the time if I could get away with it.”

There are three guests helping with the new project. Cliff elaborates, “Fred Travers, who I met when I did the Bill Emerson Reunion album, Pat White, who was recommended by Emerson, and Ronnie Simpkins. All these guys are just great musicians.”

When asked about what his plans are, Cliff is rather laid back about his aspirations. “We hope to work some festivals, and concerts, but I like being home, I have three grandchildren I love spending time with. Not to mention the fact, I am retired, and I’m looking forward to enjoying that!”

The band is committed to playing great music. Cliff says, “It was said, even after I quit, I was ahead of my time. So now we’ll see, we’ll see when my time is.”