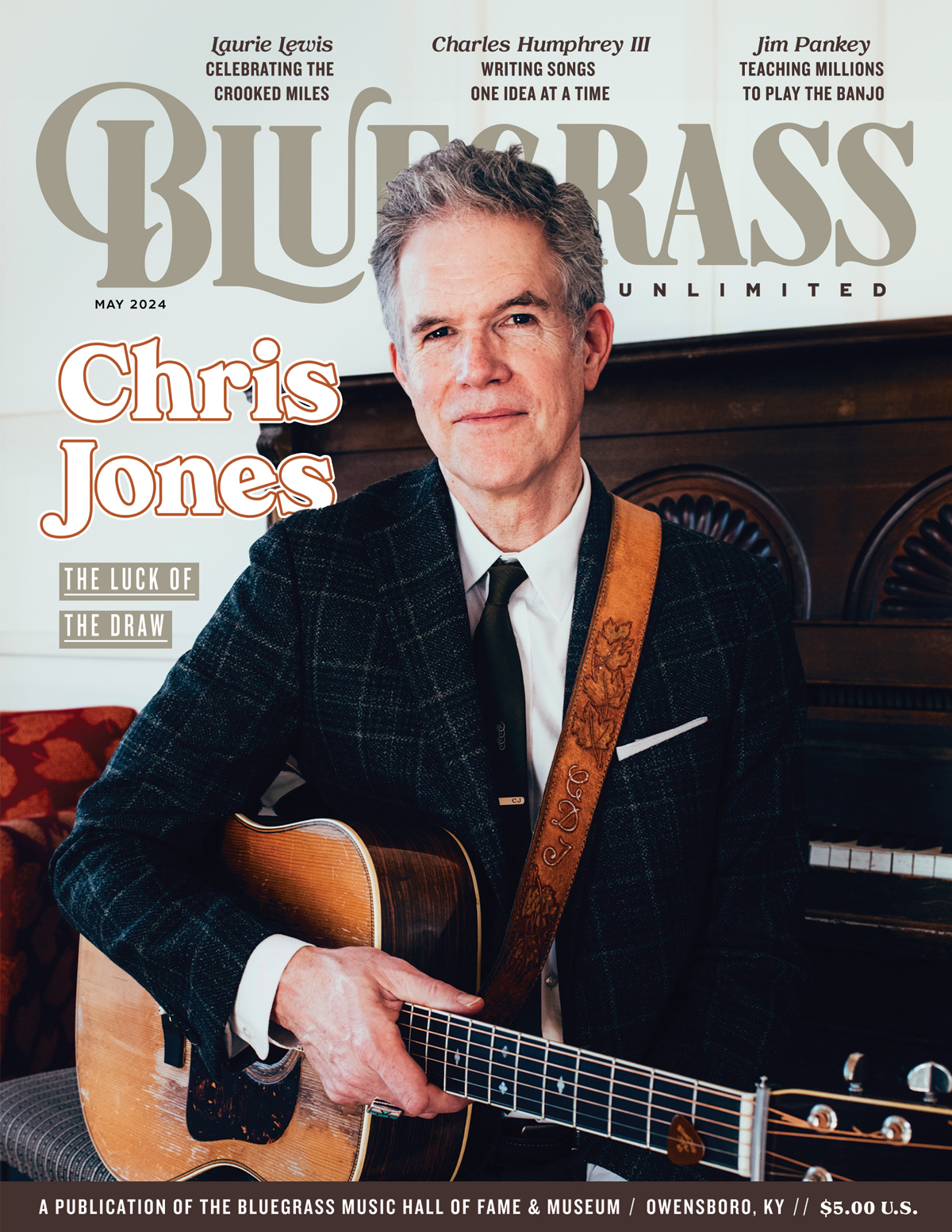

Home > Articles > The Artists > Chris Jones

Chris Jones

The Luck of The Draw

Luck plays an uncomfortably large role in life. Though we like to think we have control over our fates, the truth is that a great number of events, actions and encounters are simply out of our hands. Sometimes, God will smile upon you and you will receive an opportunity that changes everything. Sometimes, despite doing everything right, you won’t.

It’s a fact we all know to be true, but one that we are more likely to acknowledge in the latter scenario. You couldn’t have stopped the tree from falling on your house during a tornado. But what about when you’re invited to audition for an opening in a band? Or you sign a recording contract? Or you get asked to write a cover story for a magazine? Those things happen because you earn them; you did something to deserve that chance. That’s not luck… is it?

According to Chris Jones, bluegrass industry veteran and bandleader of Chris Jones & the Night Drivers, it is. Or at least, luck plays a key role. While it would be ludicrous to argue that being well-prepared, knowledgeable and passionate about an opportunity plays no part in whether or not it gets granted, it’s not everything. From where he stands, “everything is a combination of luck and creating the opportunities.”

In every chance, there is always the risk that it falls through. The course of your life is never fully yours to set. To get to where you want to go, you need to have a keen sense of when and where these lucky breaks will appear — and no one in bluegrass seems to be better at that than Chris Jones.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Chris Jones was raised with music all around him. His mother was an actress and often performed in musicals — something that a younger Chris joined her in until he hit the age of seven. Meanwhile, his dad had a tremendous passion for jazz and worked as a bartender at the famed Five Spot jazz club during Chris’s youth. This shared passion for the arts is actually what first brought his parents together, with fate crossing their paths at the Café Rienzi where they both worked, a hub for the beat movement in New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1950s and 1960s.

His introduction to roots music came from his mother’s side of the family — most notably from his bluegrass and old-time banjo-playing uncle from Kalamazoo. But it wasn’t until his parents separated and his father’s subsequent move to Albuquerque, New Mexico, that American traditional music began to dominate his musical journey. Jones credits this in no small part to the influence of his stepmother, Chris Nunn. Raised in Detroit, Nunn was an avid record collector with a passion for country, bluegrass and Motown music — a passion she shared with him. On his regular cross-country trips to see his father, she would share her music with the young Jones. Listening to the classic albums in her collection inspired him to pick up the guitar in his early teens, which soon led to him seeking lessons from Tricia Ann Eaves.

“I only took about a month of lessons with her,” says Jones of the experience. “But it was an intense and life-changing month.”

He now credits Eaves with setting him on the path to becoming a professional bluegrass musician, deeming her a mentor to him rather than just a one-time guitar teacher. More importantly, that short month of lessons instilled in a young Chris a sense of tangibility. This was something real. This was something he could do — not only as a creative outlet but as a career. So, with an early boost from Eaves, Jones was able to grow his skills enough that he began playing professionally at the age of 17.

His first gigs weren’t the kinds of bluegrass fanfare you might expect from a young hotshot. Rather, the career of Chris Jones began on a subtler path. His first paid gigs were for supporting roles: playing rhythm guitar at contra dances and backup for French-Canadian fiddlers. His first lessons in professionalism were all about being consistent and reliable, not about taking the flashiest solos or shredding at the fastest speeds. In so doing, he learned an invaluable skill for a musician: that of making others shine.

These initial opportunities, as they often do, led to new ones. The dance and fiddle music gigs he took during his first year of college in Burlington, Vermont, helped him to catch the eye of Willy Lindner from Banjo Dan & The Mid-nite Plowboys, who tracked him down on the street to get Jones to fill in on guitar with them. Banjo Dan led to an offer to join the Green Mountain Volunteers on tour, playing rhythm guitar behind dancers wearing traditional costumes. That job took him on his first international trip to Europe, which he augmented with side gigs alongside hammer dulcimer and clawhammer banjo player, Tom MacKenzie. Those gigs led to a recording session — the first in Jones’s up-and-coming career — culminating in the 1980 album Finally Tuned, released under MacKenzie’s name.

Upon returning home from tour, Jones had a musical momentum he didn’t want to lose. So at 18, Jones took a year off from his formal education and joined the local upstate New York bluegrass band, Horse Country. This put Jones in a more prominent position than his previous work, as he agreed to be Horse Country’s lead singer. “It was a big step up for me, musically,” says Jones, reflecting on his time working under bandleader Bob Mavian. “It’s always helpful to play with people who have more experience and skill than you.”

This job raised his profile, introducing him to the wider industry in a way that garnered him attention and interest. Less than two years later, this manifested as a chance to audition for Special Consensus. As he tells it now, even making the audition was a stroke of luck. For years, he’d been riding the train across America to get between his parents’ respective homes, with his father living in New Mexico and his mother living in New York. When it came time for him to actually audition for the band, he already had a trip planned to visit his father. This train trip included a long layover in Chicago — long enough that his future bandmates could pick him up from the station, play some songs together, and drop him back in time for boarding.

It wouldn’t have made sense for Jones to visit Chicago just for an audition, he didn’t have the disposable income for that. What are the odds that his family would be spread across the country like this? That he would have spent his adolescent years on Amtrak, learning the sounds and shapes of the nation from the railways? That he had a family visit already scheduled within the window of time that the band was holding auditions?

He made the audition. A few weeks later, as he was returning home from visiting his father, he got the call. Within days, he moved to Chicago.

His time playing with Special Consensus was invaluable in numerous ways, but one of the most impactful is that it is the seed from which his songwriting career sprouted. To this point, he hadn’t engaged with writing his own music — he was happy to spend his time learning the existing canon and building his understanding of the music, growing his skills as a picker and a vocalist. But upon joining, he noticed that all the other members were contributing original content to the band’s set lists and track listings. He felt pressure to pull his weight as a full-time member. So, for the first time in his musical career, he picked up the pen for himself.

“Now it’s a very important expression for me,” says Jones of his songwriting, which has since netted him numerous awards — including the International Bluegrass Music Association’s coveted Song of the Year award in 2007 for “Fork in the Road,” recorded by the Infamous Stringdusters for their album of the same name. “I love the process of it. I just love the idea of expressing something differently and doing something musically that hasn’t been done before.”

But fate was still calling. After four years with Special Consensus, there was no shortage of opportunities open to Jones. All he needed was the courage to embrace change and make the necessary leaps. So he left the band and, eventually, landed in Nashville, Tennessee. He moved there in 1989 with his Weary Hearts bandmates—Ron Block, Mike Bub and Butch Baldassari. Though the band wouldn’t last much longer, Jones’s time in Nashville would. It was a better headquarters for a working musician like Chris, opening up fractals of ever-expanding opportunities to him. And when opportunity knocked, Chris Jones answered.

Musicians that he had long admired, even that he had grown up listening to, were now calling him and asking him to fill in for specific shows or join them on tour. He toured America with The Chieftains, returning to his Irish rhythm guitar roots — even joining them for a performance on Late Night with Conan O’Brien alongside Earl Scruggs. He played at world-renowned venues, like the Lincoln Center and the Grand Ole Opry. He toured with Lynn Morris, Dave Evans and Vassar Clements — including one serendipitous gig in New York City at Café Rienzi, the very same spot where Jones’s parents first met and fell in love.

Nashville nourished more than his career as a touring musician. He also attended writers’ nights and honed his skill and passion for songwriting. And, in what may have been his most fortuitous stroke yet, he got a job at the Franklin WAKM radio station.

Chris had worked in radio before, but had never invested in it as a possible career path — he feared doing so meant he would have to quit music, something he was unwilling to do. But it was something he had always enjoyed and had an interest in. When he was in college, he ran a show of his own, featuring a variety of genres — whatever he was enjoying at the moment was his to share. His first appearance on a bluegrass show came during his time with Whetstone Run, when a bandmate asked him to co-host a one-off show with him. So when an opportunity came to work at WAKM, he seized it. “I kind of learned the ropes there,” says Jones, remarking upon the many hats he wore during his time at the station. It gave him an education, preparing him for later great things — though he did not know it at the time.

When satellite radio came calling, Jones was ready. He had the commercial radio experience from WAKM, giving him the technical proficiency to run his own show. He had deep knowledge of and reverence for first-generation bluegrass, as learned from his stepmother’s record collection and later reinforced by his time working under Horse Country bandleader Bob Mavian. And he knew how to lead a team, as he had recently started a band of his own: Chris Jones & the Night Drivers.

“If you have any other options in your career, take ’em.” That’s what Lynn Morris had told Jones when he asked her about starting his own band. He had watched the leaders he’d worked with throughout his career and taken mental notes. From observing Lynn, Greg Cahill, Bob Mavian, and the many other musicians he had worked alongside, Jones had learned that good band leadership “either involves being a good mentor to people, or working with diverse people who may not need mentorship but could use leadership to unite them with others.” Most importantly, “musical leadership — leadership of any kind — requires vision.” And Chris Jones had the vision.

He’d been working as a collaborator for his whole career, but after more than 15 years, he had his own stories to tell. He had music he wanted to write, songs he wanted to arrange, a sound he wanted to make. Working with others was valuable experience, and it was experience that he loved. But ultimately, there was always someone else with the final say on how things were going to go. Now it was his turn to hold the megaphone.

Starting his own band put Jones in a new position with fate. Before, he had been in a receiving role — as the one who gets lucky through the consideration of others, the one who seeks the opportunities to be smiled upon. Now, as much as he was dependent on others for their good grace, he was also giving it in equal measure. That’s a big responsibility to bear.

“As a bandleader, I’ve always had a view of wanting people to be themselves,” says Jones. “I try to draw out what makes them special while also having them fit into the broader musical vision.” He points out specifically that it’s important to him that he keeps his grip loose enough that there’s room for his sound to change. That’s why he tends to hire people who stick around; he isn’t interested in musicians who are just there for the gig. He wants his collaborators’ voices to influence him — to form partnerships with people who are invested in The Night Drivers as a vehicle for their own creative voice alongside Jones’s. He wants there “to be growth in [his] path,” which requires trust in the people he works with.

“My respecting the people I play with, I hope gives them a good example should they ever go into a leadership role themselves.”

Ultimately, Jones is optimistic about the future of bluegrass. From his vantage, he sees a steady enthusiasm and commitment to the genre. He sees young people, “kids who have a deep understanding of the music, who play with depth and feeling,” who he knows will create interesting and innovative projects of their own. On his international tours, he sees people who love bluegrass in all corners of the world — the Czech Republic, Japan, Spain, and more — and sees the ways that they understand the music and make it their own. He sees that people are coming to bluegrass despite differences in their backgrounds — race, gender, sexuality, class, age and ability — and are finding a home here. It gives him hope. The view from atop the mountain is bright.

Luck has played an incredible role in Chris Jones’s career, in both its ups and its downs. What if Willy Lindner hadn’t stalked the streets of Burlington to find Jones and ask him to fill in with Banjo Dan & The Mid-nite Plowboys? What if he hadn’t subbed in for Terry Herd on his radio show in the days before Sirius XM? What if the Infamous Stringdusters hadn’t centered their 2007 album around Jones’s titular “Fork in the Road,” or had chosen to record a track from a different songwriter entirely?

None of these questions or anecdotes are intended to dispute the validity of Jones’s success or to suggest he did not live up to the opportunities he was given. The course of history shows us that it is and he did. Speaking with Jones for this piece, listening to him play, and watching him helm his fellow musicians — his mastery and skill as both musician and leader are self-evident. He has earned his title as an elder statesman of modern bluegrass.

Nor is it meant to imply that his life is without the many hardships and devastating moments that could have easily derailed a career. It would have been completely understandable to give up music after the state police turned up at a Weary Hearts show to inform him that his mother had been killed in a car accident. Or in 2003, as he and his wife (and frequent collaborator) Sally celebrated the birth of their twins Sean and Joanna, only to lose Sean four months later — who could even think about going on tour again after that? How could someone ever find the words to share that pain, let alone turn it into art as Jones did with his song “It’s What You Do?”

Fate can be both friend and foe. In reflecting on Chris Jones’s early years, it is striking how many moments there were where things could have simply not taken off.

What if the universe had placed her bets differently?

It’s a question Jones grapples with as he manages his own work. Mindful of the chances he was given, he is sure to pay those same kinds of opportunities forward to talented artists who may have otherwise gone overlooked in the traditionally white and male genre of bluegrass, as can be seen in the current lineup of The Night Drivers. German-born Mark Stoffel has served as Jones’s mandolin player for nearly 20 years now, joining the band a mere five years after his emigration from the Old World in 2001. Now a naturalized citizen of the United States, he has recently begun releasing his first solo projects. In 2019, multi-instrumentalist old-time, bluegrass, and classic country aficionado Grace van’t Hof joined the lineup as perhaps the first openly nonbinary musician touring at this level in the bluegrass industry. van’t Hof has contributed far more than just their virtuosic musical skills to the present-day Night Drivers sound; they have also pioneered the visual identity of the band as in-house graphic designer, netting Grace three consecutive IBMA Graphic Designer of the Year awards. Most recently, Jones hired New Orleans-based bassist Nelson Williams in late 2023. Best known for his work with Black afrofuturist old-time musician Jake Blount and as a founding member of the supergroup New Dangerfield, it is only a matter of time until Williams starts bringing home Bass Player of the Year trophies to line his shelves — and this move will only get him there faster.

None of these hires were made as “virtue-signaling” or “affirmative action” for undeserving players, as some may be inclined to say. Hiring these musicians did not require compromising on talent or professionalism. Rather, these decisions were made out of the same deep understanding of bluegrass that has long led Jones to look beyond short-term trends and seek the truth of the music, wherever it may be found. Even if that may be somewhere as of yet unknown to us.

The facts are what they are: bluegrass is a small community and an even smaller industry. There aren’t infinite resources to dispense, so choices will always have to be made about how best to allocate them. For every opportunity that one person receives, one or more will have lost out. Sometimes this will be deserved: maybe someone hasn’t developed their skills enough yet, or perhaps they failed to put in the work to seize an opportunity when it came. Sometimes it will seem unfair: someone is deemed “not a good character fit” for a band, or someone gets offered a job simply because they know the right people. And sometimes, someone in a position of power is given two equally good options for one opening — and a choice must be made.

Who does luck smile upon?

Are we rolling a weighted die?

As we move deeper into the 21st century and further away from the traditional financial models of our industry, bluegrass must be brave enough to choose the unknown future — to let fate take control without letting our instincts push us back towards the things that we know and that are comfortable for us. It’s something that Jones talks about explicitly, as he ruminates on his hopes for the genre in the future. “A lot of the time, we expect some artist from outside the genre to make a bluegrass album, to make it a household name. But it tends to happen in surprising ways,” he says, citing the universal acclaim received by the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack in the early 2000s and the present-day breakout success of Billy Strings. “That’s something no one could have predicted. That shows that there is appeal for the music and it doesn’t need to be diluted or watered down for people to love it.”

All they need is to be given a chance.