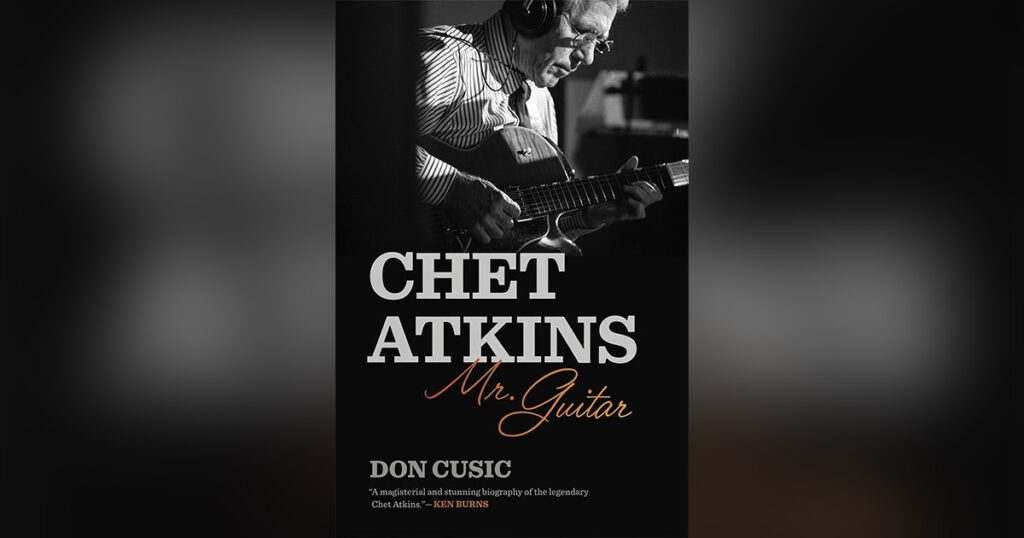

Chet Atkins Mr. Guitar

Quick! Name two of Chet Atkins’ hit singles. OK, one?

Because of his decades-long success producing hits for other acts and in so doing co-creating with Owen Bradley the fabled “Nashville Sound,” Chet Atkins’ contributions as an artist in his own right have been routinely overshadowed. Yet by the time he died in 2001 at the age of 77, he had recorded more than 130 albums (including many collaborations with fellow guitar notables).

Atkins recorded his first album for RCA in 1947 and stayed with the label as artist, producer and division executive until 1982 when he switched to Columbia for his final studio work.

While his albums sold well and reaped armfuls of awards until his later years, his singles never caught on. Of the 10 he charted in Billboard, only two made the Top 10, “Yakety Axe” (1965) and “We Didn’t See A Thing” (with Ray Charles and George Jones in 1983).

In this meticulously researched accounting, Don Cusic brings Atkins’ artistry to the forefront. A Music Row chronicler since the early 1970s, Cusic is well-suited to tying Atkins’ multiple musical threads together. He is Curb Professor of Music Industry History at Belmont University, co-director of the annual International Country Music Conference and author of biographies of Eddy Arnold, Merle Haggard, Roger Miller, Gene Autry and others, as well as The Sound of Light: A History of Gospel and Christian Music.

Cusic reveals he interviewed Atkins only twice, neither time in depth. But he compensates for the personal distance by interviews and conversations with dozens of Atkins’ intimates and by sifting voluminous details from studio logs, contemporary newspaper and magazine stories, advertising and promotional copy, liner notes, concert reviews and, yes, Music Row gossip.

Atkins’ importance as a producer faded with the arrival in the 1970s of such musical hardheads as Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, who, in spite of their respect and affection for Atkins, insisted on junking the Nashville assembly line of recording and instead picking their own songs, producers and engineers and recording with their own bands.

Leavening Cusic’s strictly historic matter are dozens of insightful and often amusing anecdotes. Among them Atkins’ very public and protective friendship with Janis Ian, who, acknowledging his eye for the ladies (except her), regularly sent him postcards from all over the world adorned with photos of buxom beauties; his love of novelty songs, e. g., “I Still Write Your Name in the Snow,” “Would Jesus Wear a Rolex?”; his fraternity bro correspondence with A Prairie Home Companion’s Garrison Keillor; his tearful desolation upon learning of the early deaths of guitar wizards and picking buddies Lenny Breau and Marcel Dadi; his angry observation that if the Country Music Association wouldn’t present its top instrumentalist award during its telecast, it ought to just call itself the Country Poets Association.

Ultimately Atkins emerges as a tireless seeker of more enchanting sounds, always eager to discover and teach new licks, explore new musical formats, design better guitars and recording equipment and put new instrumental spins on current popular songs in order to sell more records. He saw himself first and always as an entertainer. His impact in popularizing and romanticizing the guitar was, of course, immense, immeasurable and worldwide.

Regrets? He had a few. He always wished he’d stayed in school instead of dropping out to earn a living. He tried but was never able to reconcile emotionally with the father who abandoned his family and treated his talented son with indifference. And he regretted not being able to get past his shyness on stage. “I wish I did show my emotions more,” he said. “I wish I smiled more. I wish I was more of a Roy Clark type personality. But I’m not. I’m a shy, quiet kind of guy. I just try to play what’s in my heart.”

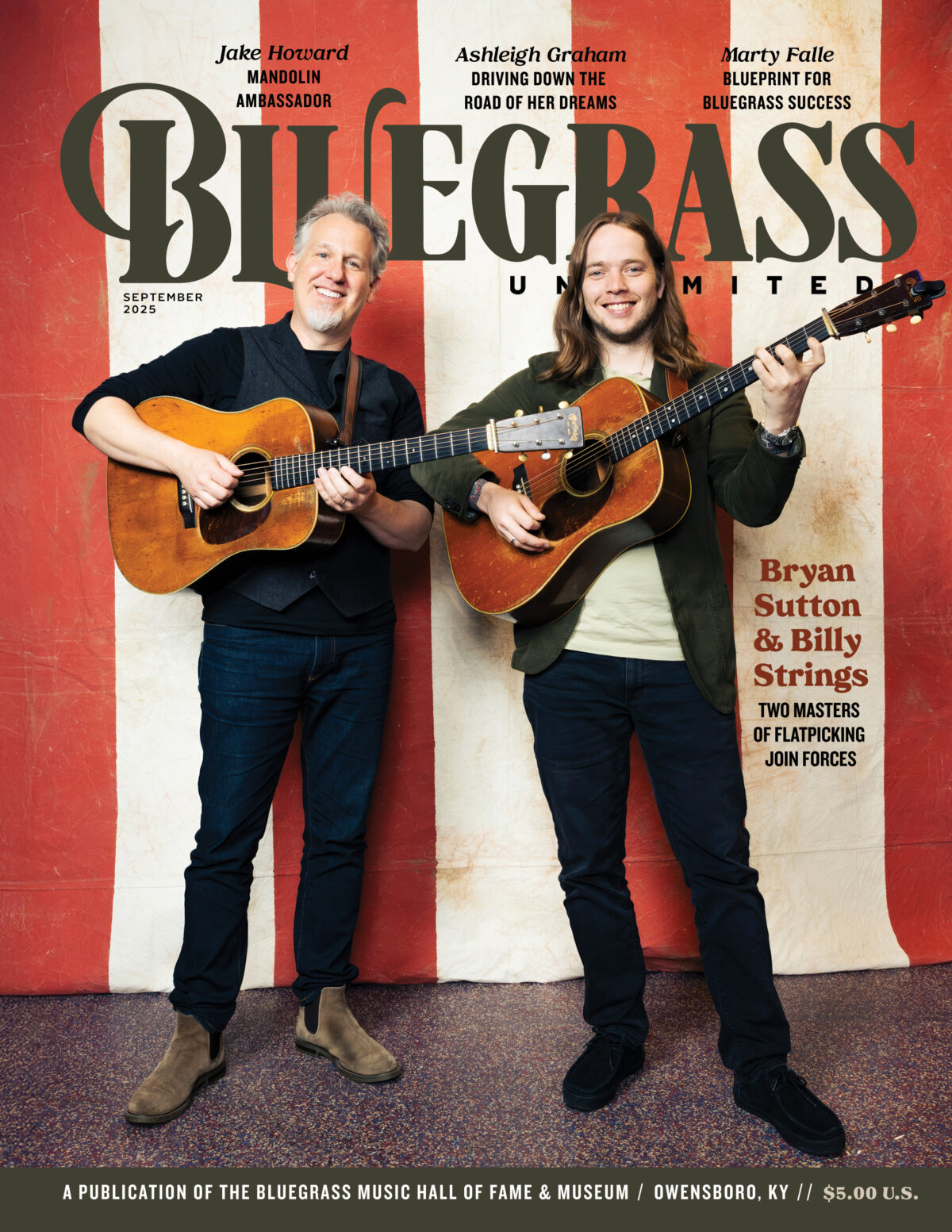

Given his mentoring impulses and capacity to be delighted by young talent, one wonders what the Old Master would make of Billy Strings.