Home > Articles > The Archives > Charlie Monroe

Charlie Monroe

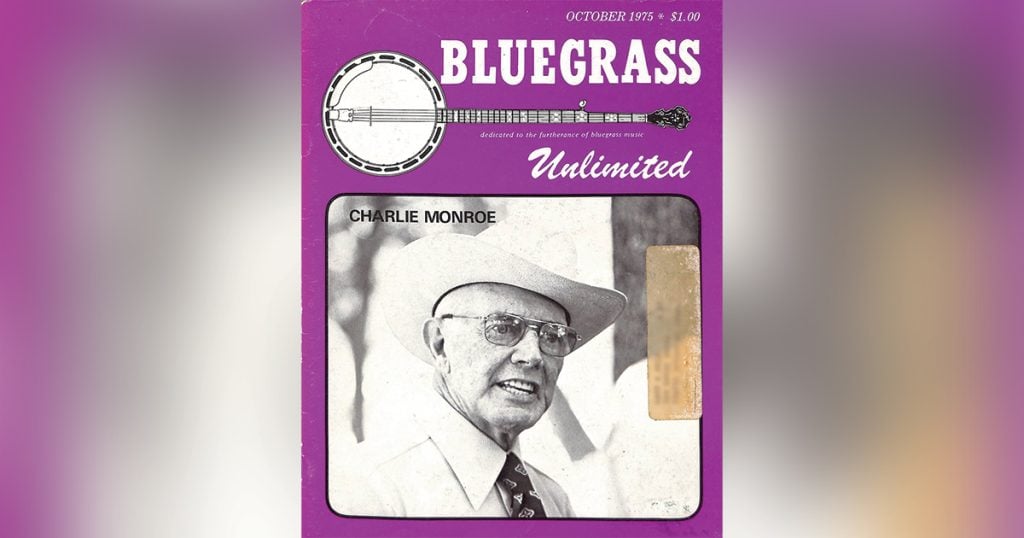

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1975, Volume 10, Number 4

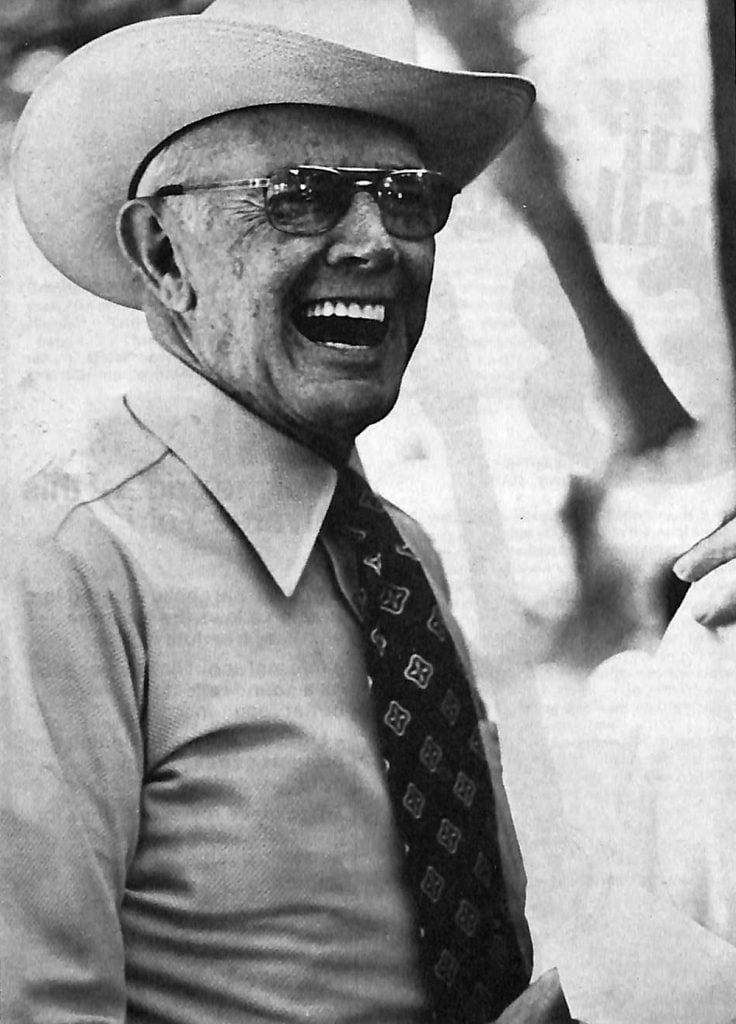

For the last four decades the name of Charles Pendleton Monroe has ranked high on the list of those who have made important contributions to old-time, traditional, country music. First, as a member of the famous Monroe Brothers duet; and second, as a vocalist and bandleader in his own right, Charlie’s record is an impressive one. Emerging from a long period of semi-retirement in the last three years, his comeback can hardly be termed anything less than quite successful and he has quickly re-established himself as a top artist.

James B. Monroe (1857-1928) and his wife, Melissa Vandiver (1870-1921), reared a family of eight children. Charlie ranked sixth in age, being born on July 4, 1903, making him a couple of years younger than brother, Birch, but eight years older than Bill. The elder Monroe owned a large farm near Rosine, Kentucky, and the boys became exposed to agricultural chores, timber cutting and sawmill work at an early age. Charlie, along with the other children, attended grade school at nearby Horton.

Music constituted another fare to which the Monroe youngsters received exposure. Charlie’s father liked to dance and his mother played accordion, fiddle and harmonica as well as sang old ballads. However, his mother’s brother, Pendleton Vandiver, “Uncle Pen,” a renowned local fiddler, provided the main musical inspiration for the Monroe boys and girls. Charlie favored the guitar, taking up that instrument as he recalls at about the age of eleven. Birch played the fiddle, younger sister, Bertha, also took up the guitar, leaving young Bill, so the story goes, with the mandolin.

Through his teens and early adulthood, Charlie remained at home, working on the farm or at his father’s coal mine and sawmill. In the latter part of the 1920’s, he and Birch went north where they worked for some time at the Briggs Motor Company, a firm which manufactured Ford parts. While in Detroit, the twosome often played their fiddles and guitars for such local social gatherings as parties and dances. By this time, they had heard phonograph records of artists like Charlie Poole, the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Bradley Kincaid and the Skillet Lickers as well as the music learned back home. After a while, the boys got laid off and returned home just in time for Christmas.

Soon, however, the lure of the northern industry drew Charlie and Birch back to the city. This time they went to Hammond, Indiana and the Sinclair Oil Company where Charlie also played on the baseball team. Kentucky seemed less attractive to the boys as both their parents had died. Not long afterward, Bill, now eighteen, came up and he too went to work at Sinclair. Charlie, however, found himself switching employment to Standard because he was fired due to fighting.

At Standard Oil, Charlie continued to work and played on their baseball team. Although the brothers didn’t play much music, they did attend area square dances. At one of these local affairs in Hammond, Tom Owens, square dance caller at the WLS National Barn Dance saw the Monroes, their partners and two friends, Mr. and Mrs. Larry Moore. He asked the four couples to dance with the WLS Road Show. Their acceptance led to the Monroe Brothers being introduced to professional show business. In addition to their dancing, the boys also did some singing. As Charlie recollects, they did a lot of Carter Family and Karl Davis-Harty Taylor numbers. Among other places, they worked at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair with the exhibition square dance team.

Not long afterward, a representative of the Texas Crystal Company asked the Monroe Brothers to go into radio work under their sponsorship. Birch preferred to keep his job at the oil refinery, but Charlie and Bill accepted and were soon broadcasting from station KFNF in Shenandoah, Iowa. Three months later, still working for the same company, they switched to WAAW in Omaha where they remained for approximately a half-year. During this time the Monroe Brothers became an exceedingly popular radio group. Although they worked only as a duet, they had the able assistance of Byron Parker, “The Old Hired Hand,” as announcer. By all accounts, the latter was one of the best radio salesmen of his era and played an instrumental part in the radio success not only of Bill and Charlie, but also the Mainers, Snuffy Jenkins and Homer Sherrill. Parker died in 1948.

In 1935, the Monroe Brothers switched their base of operations to the Carolinas. This change to the South probably constituted an extremely decisive move for them. For Charlie, the move placed him in a geographic area whose people took him to heart as it did few entertainers. For the brothers, it placed them on Bluebird Records and also on a series of regionally popular radio stations including WIS, Columbia; WBT, Charlotte; WFBC, Greenville; and WPTF, Raleigh for the next three years. Although the Carolinas boasted a great deal of tremendous home-grown talent including the Callahans, Mainers, Bolicks, Morrises, Dixons and the Tobacco Tags, Bill and Charlie Monroe more than held their own with the competition.

While at Charlotte the Monroes left Texas Crystals and went to work for J.W. Fincher’s Crazy Water Crystals. Early in 1936, Eli Oberstein of RCA approached the brothers about recording for Bluebird. Seemingly unenthusiastic, they finally entered the temporary studio at Charlotte on February 17, 1936. They cut ten numbers that day, including their biggest hit, “What Would You Give in Exchange For Your Soul.” This old hymn became so popular that the next year the boys waxed three additional versions of it and the Dixon Brothers added three more. In four more sessions over the next two years, the Monroe Brothers recorded a total of sixty sides, all of them released on RCA’s Bluebird label. Thirty-two of these numbers are now available on a new two-album set.

The recorded repertoire of the Monroe Brothers was composed of nearly equal divisions of sacred and secular material. As Charlie remembers, the brothers did little songwriting in this period of their lives, but tried to select material suited to the Monroe style. In so doing, it seems likely that they helped a number of important old-time songs to later enter into bluegrass. Such numbers include Buster Carter and Preston Young’s “I’ll Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms” (which, contrary to bluegrass and country neophytes, originated with neither Flatt and Scruggs nor Buck Owens), Foster and Rutherford’s “Six Months Ain’t Long,” “Watermelon On The Vine,” “New River Train,” and “Darling Corey.” They also recorded a number of songs previously waxed by the Carter Family such as “Foggy Mountain Top,” “Little Joe,” “Weeping Willow Tree,” and “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Old hymns transmitted from one generation to another with the help of Monroe Brothers’ records included “How Beautiful Heaven Must Be,” “What Would The Profit Be,” and “When Our Lord Shall Come Again.” Since many other acts of the time had begun to add some variety to their stage shows, Charlie and Bill Monroe followed. They remained a two-man group, but for a time, Bill did some fiddle playing and Charlie took up the banjo as part of a comedy routine. However, this seemed something less than a great success and as a result, they returned to the more familiar duet singing and mandolin-guitar instrumentation.

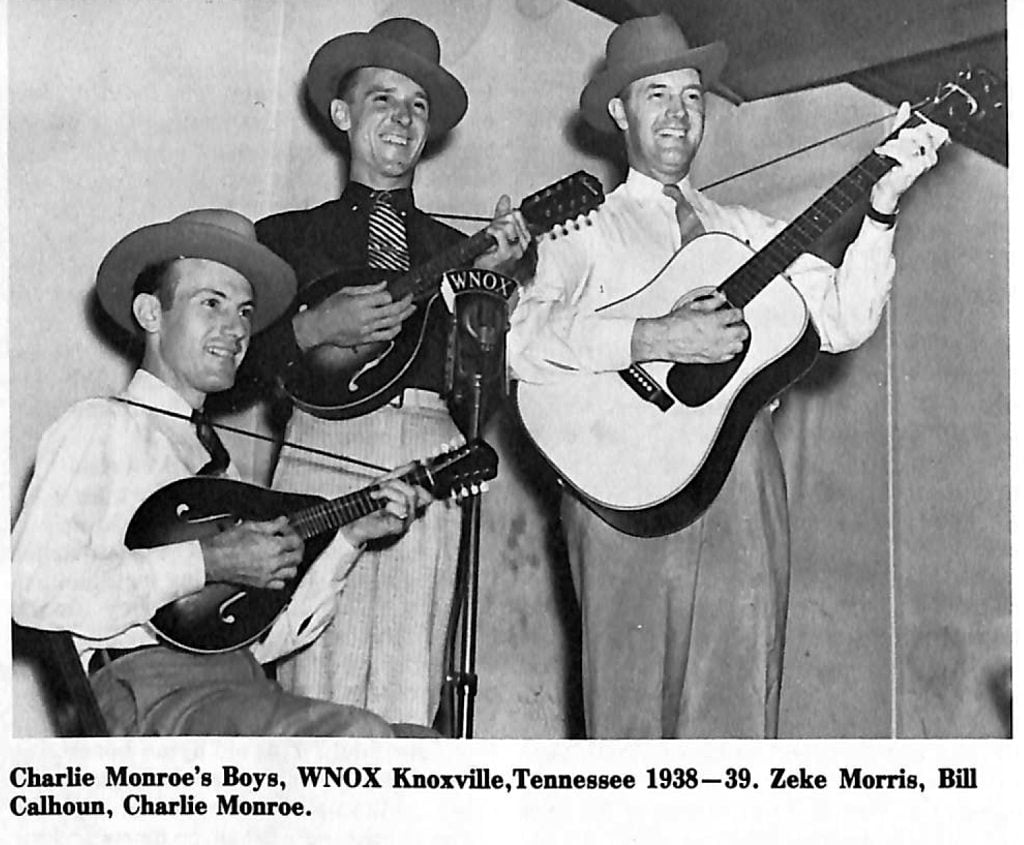

In mid-1938, Bill and Charlie Monroe, like most other brother duos at one time or another, began to have some differences. They were working in Raleigh when the split came; each going his own way. Bill to Little Rock, Arkansas and Charlie to Knoxville, Tennessee. There in the metropolis of East Tennessee, he was hired by Lowell Blanchard at WNOX.

At Knoxville, Charlie had only two band members in his group – Bill Calhoun, a guitar player and tenor singer, along with “Lefty” Frizzell (not the better known “Lefty” Frizzell of the 1950’s), a southpaw mandolin player. After his departure, Zeke Morris, formerly of the Mainer Mountaineers and his own brother group, joined Charlie on mandolin. From WNOX, the Monroe Boys went to Roanoke, Virginia, where they worked at WDBJ for nearly a year.

During this time, Charlie cut two more sessions on Bluebird at Rock Hill, South Carolina in September, 1938 and February, 1939. Zeke Morris and Bill Calhoun assisted him both times with a total of eighteen sides being recorded. All the songs fell into the sacred or sentimental category and included such titles as the beautiful “No Home, No Place To Pillow My Head,” a song probably learned from Karl and Harty; a cover of Roy Acuffs popular hit, “Great Speckled Bird,” which combined both the No. 1 and No. 2 versions; and the old sentimental ballad, “Black Sheep.” Although of excellent quality, these records probably did not sell as well as the Monroe Brothers recordings or Charlie’s later efforts on Victor, since they are more difficult to find today.

Throughout the decade of the 1940’s, Charlie Monroe and his Kentucky Pardners provided country music fans with top-flight entertainment. North Carolina, Virginia, eastern Kentucky and Tennessee constituted the areas of his greatest activity. He played other places for brief periods. In late 1939, he went to the WWVA Jamboree at Wheeling and stayed for several months. By this time, Charlie had replaced the three-man group that had worked on his last Bluebird session with a full-sized band, the Kentucky Pardners, that included Dale Cole on fiddle, Tommy Edwards on mandolin, Tommy Scott on guitar and Curly Seckler on four string banjo and tenor singer. Throughout the next decade, Charlie continued to maintain a full band for his personal appearance schedule including a comedian and a girl vocalist. Charlie Monroe strived to entertain his audiences by offering them a wide variety of talent. His popularity with the fans of that period attest to his success as a country showman.

Charlie appeared on a variety of radio stations during the decade. From Wheeling, he went to WHAS, Louisville and the Renfro Valley Barn Dance. Oddly enough, Charlie recalls this radio venture in his home state as being the only one where he lost money. Leaving Kentucky in the spring of 1940, he put together the first of his now legendary tent shows which opened at Almo, Georgia in May. The tent seated 2,000 spectators and at a dollar a ticket, Charlie managed to keep it filled six nights a week, all summer long.

When the tent show season ended in the fall of 1940, Charlie brought the Kentucky Pardners to Greensboro, North Carolina and station WBIG. This remained his major base of operations for the next twelve years, although he occasionally left to do stints on other radio stations including WNOX, Knoxville; WBT, Charlotte and WBOK, Birmingham. For quite some time during the war, he worked on a series of seven stations in Virginia and North Carolina including WBIG and WSJS, Winston-Salem, doing his own daily show, “The Noonday Jamboree.” Man-O-Ree, a laxative which Charlie had manufactured, sponsored the show and he made up transcriptions to play when unable to play the shows live. Fortunately for Charlie Monroe fans, these transcriptions were preserved for posterity and David Freeman of County Records released two albums from them last year. During the winter months, the band played school houses. Charlie contends that there is “not a school house in the radius of 200 miles around Greensboro we didn’t play.” In fact, the Kentucky Pardners usually played them several times with little or no loss in crowd appeal.

Except for a summer vacation and a two-week Christmas break, the Kentucky Pardners maintained a heavy personal appearance schedule. Charlie operated a large tent show with its own light plant. His wife, the former Elizabeth Miller whom he married in 1935, handled the bookings and the troupe usually played to capacity crowds, for two shows daily, six days per week. The tent show operation was a costly one, but through hard work and thousands of loyal fans, Charlie made it pay.

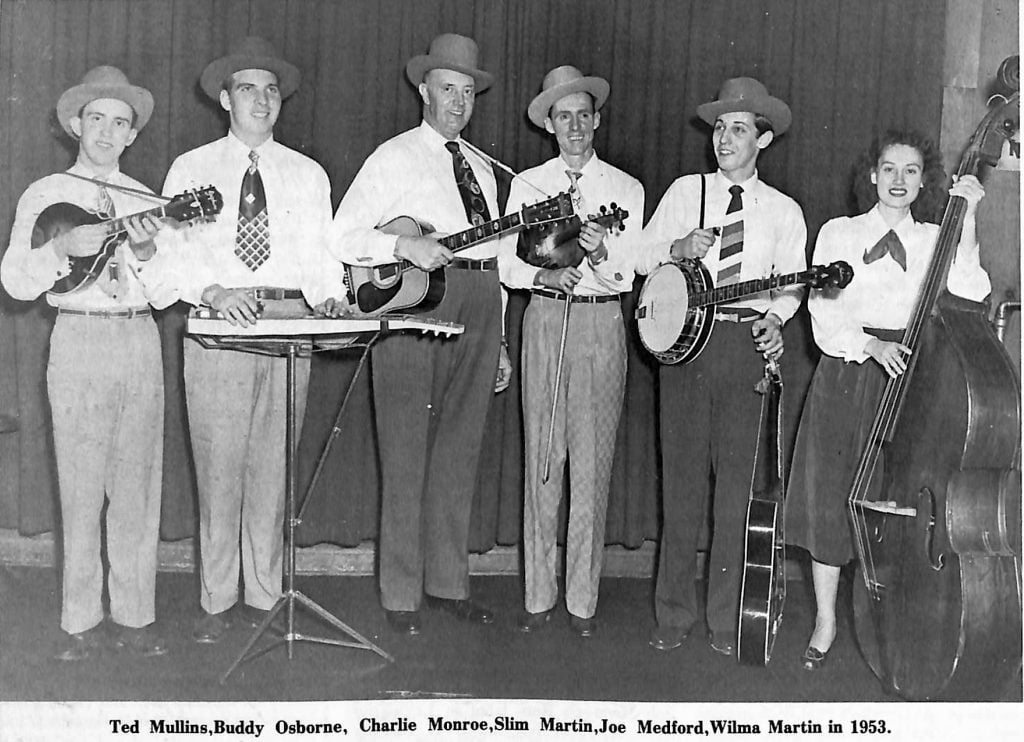

Charlie Monroe played an important part in the training of many young traditional musicians through those persons employed in the Kentucky Pardners. Mandolin players and tenor singers in particular gained valuable professional experience in their work with Charlie, including Curly Seckler, Ira Louvin and Red Rector. Lester Flatt, most famous as a lead singer, played mandolin and sang tenor with Charlie for some time and thus widened his professional horizons. The late Dave “Stringbean” Akeman also worked with Charlie prior to going to Nashville to join the Blue Grass Boys and then the Opry. The late James “Slim” Martin, a notable fiddler, harmonica player and comedian who also worked with Molly O’Day and with the Bailey Brothers, played with the Kentucky Pardners off and on for several years as did his wife, Wilma. Other longtime stalwarts with the Charlie Monroe band at various times included fiddlers Paul Prince, Birch Monroe, Lance and Maynard Spencer; guitarists Larry “Tex” Isley, Rex Henderson and Orne “Buddy” Osborne and bass player Lavelle “Bill” Coy.

Charlie Monroe and his Kentucky Pardners did forty-four additional sides for RCA Victor between 1946 and 1951. As with the early recordings, both secular and sacred material were waxed with a slight predominance of the former. The repertoire contained train songs like “That Wild Black Engine” and “Bringing In The Georgia Mail,” both of which featured Slim Martin’s spirited harmonica. It also included sentimental classics like “I’m Coming Back But I Don’t Know When” and “Mother’s Not Dead, She’s Only Sleeping,” the latter performed as a duet with Curly Seckler. Probably his most popular number, “Down In The Willow Garden,” the old murder ballad, was recorded at his March, 1947 session in Chicago with the aid of Robert Lambert, Tex Isley, Slim Martin and Ira Louvin. At his two Nashville sessions in 1950, Jerry Rivers and other members of the Hank Williams band provided instrumental assistance. At Charlie’s final RCA session held in Atlanta in May, 1951, former sidemen Osborne, Isley and Martin returned to back him along with Clyde Baum, an excellent mandolin player who had formerly worked with Johnny and Jack and the Bailes Brothers at KWKH. Oddly enough, although most of Charlie’s post-war recordings featured an electric guitar, they seem to have antagonized few of the old-time fans who continued to enjoy his special brand of music.

In the early fifties, Charlie began to relax somewhat from his heavy schedule and to spend more time at his farm at Beaver Dam, Kentucky. In 1952, he switched to Decca records, recording “I’m Old Kentucky Bound,” one of his most popular numbers. He waxed “Find ’Em, Fool ’Em and Leave ’Em Alone”/“These Triflin’ Women,” the only recordings made in his hey dey with bluegrass banjo (played by Joe Medford). These sides are the only ones which Decca failed to include on the album, “Bill and Charlie Monroe.” Charlie did his second and last Decca session in August, 1956.

In 1952, Charlie left Greensboro and went back to Kentucky. Soon, however, he got a call from J.L. Frank and went to KWKH in Shreveport and the Louisiana Hayride. Buddy Osborne, Tex Isley, the Spencer Brothers, and Slim and Wilma Martin also went along. After about a year, he again returned to WNOX and Lowell Blanchard’s Mid-Day Merry-Go- Round.

From Knoxville, Charlie went to WPAQ, Mt. Airy, North Carolina, doing daily noon-time radio shows. He also did a Wednesday evening half-hour television show at Roanoke, Virginia for Bunker Hill Beef and another one on personal appearances the other week nights and followed his time-honored practice of taking off on Sundays.

In March, 1957, Charlie and Betty retired to their farm at Beaver Dam. For the next decade and a half, he made only a few public appearances. Charlie ran the farm, operated a coal mine and generally enjoyed rural living.

A notable exception to his absence from the musical world came in 1962 and 1964 when he recorded two albums for Bob Mooney’s Rem label in Lexington, Kentucky with full bluegrass backing. J.D. Crowe played banjo on both albums and the first album also featured Paul “Moon” Mullins and B. Lucas of the Renfro Valley Barn Dance on fiddles. The songs combined a mixture of Charlie’s old hits with five songs which he had not recorded earlier, such as “Mother’s White Rose” and “We’ll Love Again Sweetheart.” Subsequent to their initial appearance on Rem, the albums came out on Starday and are currently available on A.L. Phipps’ Pine Mountain label.

Had Charlie’s wife, Betty, not become ill with cancer in the middle sixties, he might well have stayed contented and retired in Kentucky. However, the bout with illness proved to be a losing one and Betty died in 1966. During her fight against the disease, the Monroes moved to Bloomington, Indiana, and medical expenses forced Charlie to work for Howard Johnson’s Restaurants and the Otis Elevator Company.

After Betty’s death, Charlie still did not emerge from retirement although he played occasionally at the Brown County Jamboree at Bean Blossom, Indiana. He also played at the O’Tuck’s Day Celebration at Hamilton, Ohio, in the fall of 1969. In the meantime, he remarried and moved to Tennessee. His new wife, Martha, claimed that the town of Cross Plains, ten miles south of the Kentucky border, was “as far into Tennessee as I could get him” to go. A few of his recordings were reissued, including a Camden album of late forties Victor materials entitled “Who’s Calling You Sweetheart Tonight.” In addition, six cuts on the Monroe Brothers’ album actually featured Charlie and his band. Two numbers in the Vintage series and six songs on Decca were also by him. These helped to maintain interest in the man and his music. For all practical purposes, Charlie Monroe remained in retirement until the summer of 1972.

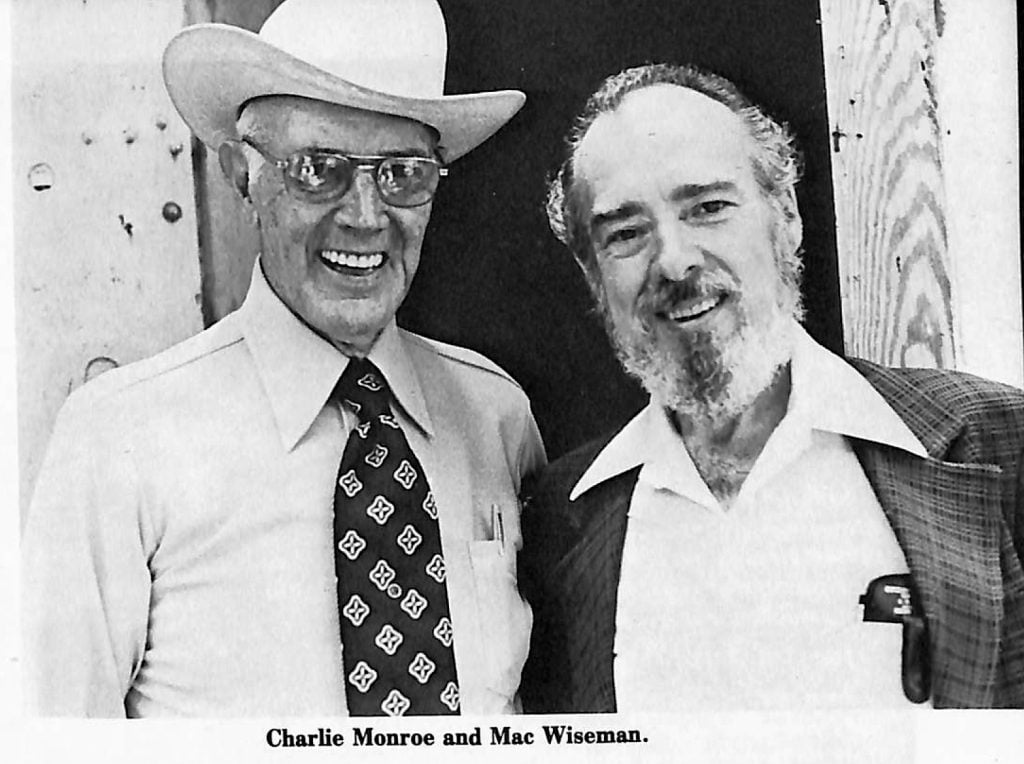

In 1972, Jimmy Martin, an old fan of Charlie’s from the Knoxville days, persuaded him to appear as a special guest at two Carlton Haney festivals – Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and Camp Springs, North Carolina. Jimmy Martin’s group with backing by Ronnie Prevette, Kenny Ingram, and Gloria Belle, Charlie made a tremendous impression. He sang some duets, Monroe Brothers style, with Everett Lilly at the Pennsylvania event. At Camp Springs, he acquainted thousands of old fans with his music and also won hosts of new admirers. Before many weeks had passed, Charlie’s two guest spots seemed to be expanding into a whole new career.

In the winter of 1972-73, Charlie Monroe continued to make occasional appearances with Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys. In early spring, he cut a new album for Starday with backing by the Martin band (an LP which has belatedly been released). This recording included some of Charlie’s best numbers from the old days like the beautiful, “Time Clock Of Life” which Victor had never reissued and some other songs previously unrecorded.

In the summer of 1973, Charlie Monroe appeared at many bluegrass festivals and was very well received. Gloria Belle, long-time girl vocalist with Jimmy Martin, worked with him, singing tenor and playing mandolin. Part of their appearance at the Hugo, Oklahoma festival was shown on NET television. Charlie moved to Reidsville, North Carolina, and started a local jamboree and also continued to work at the Carlton Haney festivals.

Throughout the summer of 1974, Charlie Monroe worked another heavy schedule of festivals with a full band, the Dominion Bluegrass Boys, Clarence Hall, J.A. Midkiff, Grady Bullins, Cliffe Mabe and Ron Pinnix. Two of the old Kentucky Pardners, Slim and Wilma Martin, also appeared frequently with their former leader. Charlie worked this band until September, 1974, usually alternating weekends with festivals and the jamboree at Reidsville.

Since last fall, Charlie has worked mostly with some of his original Kentucky Pardners – Slim and Wilma Martin, Olen Gardner along with Grady Bullins, Audine Lineberry, Roy Russell and Charlie Chaney (on banjo). Actually, from the time of his Camp Springs appearance of 1972, Charlie endeavored to re-unite as many of the group as possible on shows at which he worked. Although he has been plagued by illness throughout the past winter, Charlie Monroe has kept hard at work in the last three years to again give the people of North Carolina and the remainder of the country the type of entertainment and traditional string music which made him so popular and well liked in bygone years.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thanks for the article, my dad was Buddy Osborne, I’ve been looking for more information about his years playing.