Home > Articles > The Archives > Carrying On Without Lester

Carrying On Without Lester

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1979, Volume 14, Number 5

“Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time…

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

“It’s just not going to feel right without Lester Flatt,” Little Roy Lewis said to no one in particular as he steered The Lewis Family’s large touring bus into the Lester Flatt Bluegrass Park near Pinnacle, North Carolina, one day last June.

Slightly over a month earlier, The Lewis Family had sung “Precious Memories,” “Farther Along” and “I’ll Meet You in the Morning” at the funeral of their friend who had died on May 11 in a Nashville hospital. It was Flatt who had put young banjo player Lewis Phillips, son of Janis Lewis Phillips, on one of his albums, even before The Lewis Family themselves recorded their young star. It was also Flatt, who just a couple of months before he died, wrote young Lewis a personal letter wishing him luck on his upcoming national television appearance with Carol Burnett and Dolly Parton.

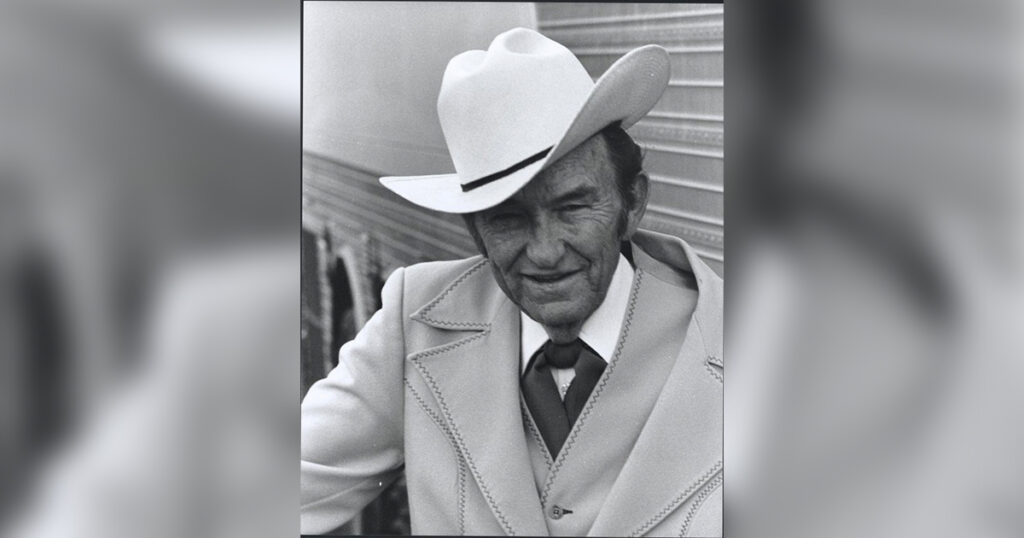

The start of the Seventh Annual Mount Pilot Festival founded by Lester Flatt came on June 20, one day after what would have been Flatt’s 65th birthday. Five years earlier, for a cover story in Bluegrass Unlimited, Flatt talked about moving the festival from land he leased at Mt. Airy, North Carolina, to the land he bought at nearby Pinnacle, within view of majestic Pilot Mountain.

In that article also, Flatt was asked if he ever thought about retirement. He pushed that famous thin straw hat back on his head and said, “I don’t think there’s anybody who retires in this business. I enjoy performing now as much as I ever did. It gets in your blood, and you’re not satisfied unless you’re performing…Of course, lots of times you’d like to have more home life, but I’d still do it over.”

One of the performers at Pinnacle this first year of the festival without its founder was Chubby Wise, the great fiddle player who was part of those days when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs worked with Bill Monroe.

“We’ll miss him, of course,” Wise remarked. “I was on the last live album Lester did; at Church Hill, Tennessee, in mid-August of last year. His boys backed me while I was on stage just before he came on. As I left the stage, Lester came on and called for me to come back. He asked if I would mind playing ‘Chicken Reel’ with him. While at Church Hill, I visited him in his motel room, and we talked about the old times like we always did.

“He especially like to tell one story about me. I was bad about playing poker, and once I ran short of money and pawned my watch. Not long later I was playing pool with Earl (Scruggs), and as I drew back my pool stick for a shot, Lester said, ‘Chubby, what time is it?’ He knew full well what had happened to that watch!” The death of Lester Flatt has left the future of several people hanging in the air. For Flatt’s long time friend and personal manager, Lance LeRoy, questions remain about what will happen to the annual Pinnacle Festival and his own life without Flatt.

“We want to continue this festival annually in Lester’s name, as a tribute to him,” LeRoy said. “We’re not trying to capitalize on his name, this was the only festival Lester ever owned, and I think he would want us to continue it.”

LeRoy, who comes from the small Georgia town of Tignall, was with Flatt 10 years and four months. With a Tennessee bank, he is co-administrator of Flatt’s estate. “Lester called me at 7 o’clock one morning and gave me the name for my talent booking company, The Lancer Agency. I didn’t like the name then, and I still don’t, but I had asked his advice and that’s what he gave me. If I didn’t want the name he suggested, I shouldn’t have asked for his help.” LeRoy remarked.

With Flatt gone, The Lancer Agency now handles bookings for The Bluegrass Cardinals (who sang at Flatt’s memorial service at Hendersonville, Tennessee), Buddy Spicher, Wilma Lee Cooper, Red Allen and Don Stover, according to LeRoy.

“I last talked with Lester the Tuesday night before he died on Friday,” LeRoy recalled. “I mentioned a date he had coming up in Oklahoma, and I asked if he would be able to work it. He shook his head ‘no’ and said he didn’t think he would ever work again. The day after he died, a letter from one of his fans arrived in our office. Ironically, the letter was postmarked the day before he died, and the fan told Lester in the letter to slow down on his road schedule or else he would kill himself. I know that person must have felt bad when he died.”

LeRoy noted there was a lot of criticism of Earl Scruggs after Flatt’s death for not attending either the Hendersonville or Sparta, Tennessee services. LeRoy commented, however, “I think the one person Lester would have liked to see the most at his funeral was Earl. The people at the funeral home had even reserved a seat on the front row for Earl. Earl likes publicity as much as anyone, but not that type. He’s shy by nature, and I don’t think he wanted to be made into a spectacle just by attending the funeral.

“When Earl visited Lester in the hospital after Lester’s brain hemorrhage in November, I think Earl said his goodbyes to Lester at that time. Lester and Earl once did a song together called ‘Give Me My Flowers While I’m Living.’ To my way of thinking, Earl brought Lester flowers while he was still living.”

Not long after the Pinnacle festival, I encountered The Nashville Grass at the Eleventh Annual Georgia State Bluegrass Festival near Lavonia, Georgia. Charlie Nixon, Flatt’s long time friend and a Dobro player for The Nashville Grass, commented, “When Lester was in the hospital the last time, he asked Curly Seckler to hold the show exactly the way Lester had it. We were making all our festival dates without Lester at that time. He never implied he wouldn’t go out with us again. He just knew he had to slow down some.

“We’ve had a lot of letters and telephone calls asking us what The Nashville Grass is going to do now. Well, we’re going to continue as long as the bluegrass music promoters and the fans will let us. We’re the last hope for people to hear Lester Flatt’s music as he had it when he died. The key is the promoters putting their trust in us. If they hear us once without Lester, I think they will want us back for another show.”

Nixon added, “I want the promoters to know The Nashville Grass plans to continue. We’re not going to cram ourselves down their throats. We’re just going to present ourselves as we are and let the fans accept us if that’s what they want. We have enough faith to think there are people who want to hear Lester Flatt’s show.”

The band member said the entire group met in a 90-minute session with the board of directors of The Martha White Flour Company recently, and the board gave their permission to The Nashville Grass to continue using the Martha White name and also the name of the group itself which resulted from a contest. Recently the group had their first album released since Flatt’s death.

Nixon said Lester Flatt’s participation on the album, “Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass…Fantastic Pickin’,” marks the last recording work by Flatt. “Lester played rhythm guitar for about three or five tunes when we did that in October of 1978 in the Charlotte, North Carolina, studio of Arthur Smith.”

Another member of Flatt’s group, who has recently been doing work with Earl Scruggs and Vassar Clements as well as the post-Flatt Nashville Grass, especially has memories of Lester since the bluegrass legend took the youngster under his wings and into his home.

Marty Stuart was the youngest member with the group when they worked road dates with Flatt. “I don’t think anything really has to be said about Lester. His life speaks for itself,” Stuart remarked. He continued, “Lester Flatt taught me to take things slow, step by step. In his last years, he never burned up the record charts but he was still loved by his fans. The great thing about Lester Flatt was the longevity of his career.”

Marty continued, “They buried Lester in Sparta, Tennessee, on a Monday. The following Friday I was with Vassar Clements going to a concert. Outside of Nashville, Kenny Ingram came on the C.B. radio. He was riding on Jimmy Martin’s bus. Kenny told me to shut up because he wanted me to hear something. Then he put on a tape of an old Flatt and Scruggs recording. Just about that same time, I looked up and saw the Sparta-Cookeville exit off the expressway. It was all I could do to hold the tears back.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Who is going to fill his shoes?