Home > Articles > The Archives > Carl Sauceman: The Odessey Of A Bluegrass Pioneer

Carl Sauceman: The Odessey Of A Bluegrass Pioneer

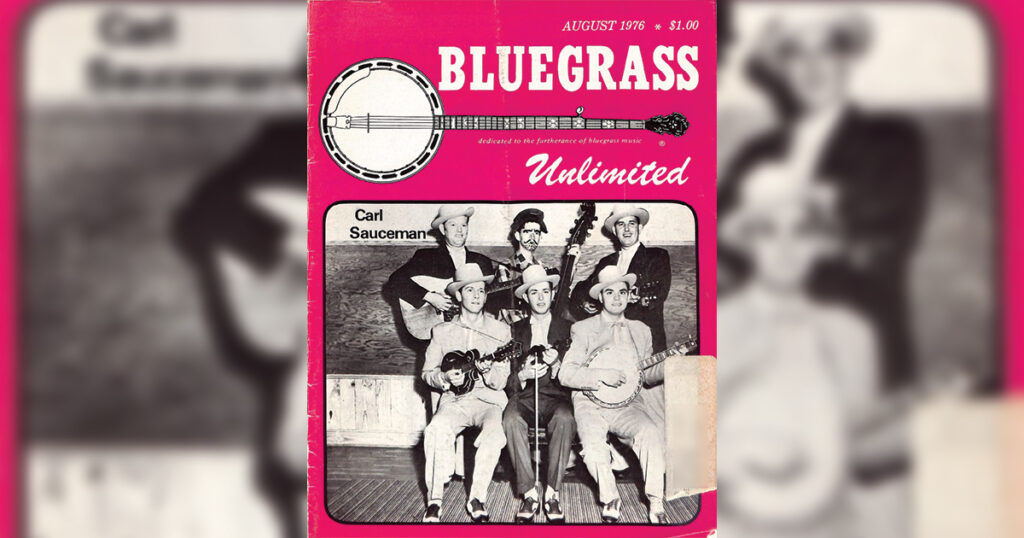

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1976, Volume 11, Number 2

Carl Sauceman is a pioneer of whom all too little is known. As a youth, he and his younger brother J.P. Sauceman both witnessed and participated in the changes which transformed the mountain style music of the 1930s into modern bluegrass. Up to now, little was known of him save for a few, mostly 78 rpm records, which nevertheless manage to document most of the important phases of his career. Unfortunately these were made for small companies which could offer only limited distribution, which has meant that his name has become a household word only to dedicated collectors who have been fortunate enough to obtain copies. Their Mercury sides made around 1947 are among the very first to reflect the stirrings of the revolution that bluegrass was to become. Ken Irwin of Rounder Records and I were fortunate enough to interview Carl Sauceman at his home in Gonzales, Louisiana one evening in October, 1973. We encountered a robust, youthful man who obviously set great store by his accomplishments even while displaying excessive modesty about many of them. Still, he recalled incidents of many years ago in detail and with pleasure as he remembered them. The following is a transcript of that evening’s conversation. It has been considerably edited to provide continuity and clarity, though basic information and observations have in no way been altered. Subsequent telephone conversations with Mr. Sauceman have helped to clarify certain details, and these have been entered into the transcript and made a part of it. Many questions from the interviewers have been omitted, again because I felt it would enhance the continuity – and because in many cases the answers turned out to be more perceptive than the original questions.

Rounder Records is preparing a reissue of the important early Sauceman sides, which should be available later this year. A documentary with discography will be included.

In a recent (January, 1976) conversation, Carl Sauceman told me that he is planning to retire from the direction of his radio station WSLG in Gonzales, Louisiana and organize a new band. He’s received more than a little encouragement from Bill Monroe and with his new group appeared at this year’s Bean Blossom festival. There could be no more appropriate year than 1976 to welcome back this important veteran of the music we love.

The Interview

I was born March 6, 1922 in Bride Hope community in Green County, Tennessee. My father was a professional gospel singer who would follow ministers all over the country. They would hold revivals and send for him to come do the singing.

RKS: With a group or by himself?

By himself, and its been said many a time that he saved more souls than the minister did. I can remember when I was a very small boy him coming home with carloads of stuff like groceries that people would give him, and even some money. We stayed home by ourselves all week looking forward to Dad coming home on weekends. He’d always bring candy and money to buy clothes and other stuff.

We were the type of family who got out of bed, went to the breakfast table. He would say blessing and after we’d eaten breakfast we would all kneel while he prayed. At noon we would do the same thing – and afterwards Dad would go off by himself. One day I got curious about where he was going and followed him out past the old corn crib where there was a long drop-off to the river. It was almost a straight drop, but you could go down by holding onto a tree and going around some rocks. He saw that I’d followed him and told me to go back. I did, but after I’d gone out of sight I sneaked back to find out where he was going. I got to the edge of the bluff and peeked over. I couldn’t see him, but I could hear him talking. I couldn’t tell what he was saying, so I kept inching closer and closer. Finally I saw what he was doing – he was on his knees praying. At the same moment I accidentally kicked some gravel and he looked up. When he saw me he made me come down and kneel between his knees while he prayed. It’s probably an exaggeration to say we stayed there for two hours, but that’s what it felt like.

At night after supper we had no radio or television. So one member of the family would have to read from the Bible. My father wasn’t an educated man, and he never read anything else, not even a newspaper. But if he was sitting across the room and you came to a word you didn’t know while you were reading, he would tell you. I found that John was easier to read, so I’d always turn to that chapter.

RKS: Where did you learn country songs?

My mother would sing to me. She knew a lot of old, old songs, and we learned others by just going around, seeing different people. And of course there were records at that time. I’ll never forget when I was a child going to school I’d pass these houses and hear Mainer’s Mountaineers singing those old songs they did on Bluebird records. If I heard a song that way one time, I could sing it the next time I heard it. I had a first cousin that had an old crank-up record player. I remember that he had “Maple On The Hill” by Mainer’s Mountaineers, and “Take Me In The Lifeboat” and all those songs. If I was walking to school and heard them I would always stop, which would make me late. By the time I was in third or fourth grade I’d get to where I would walk by my uncle’s house, because he has a radio and I could listen to the Grand Ole Opry. And I remember the first time I ever heard Charlie and Bill Monroe.

So every Saturday night I’d walk to my uncle’s house, but I was so small that I’d be afraid to walk back home by myself. It was only a mile, but I was so scared that I’d always run. One night a big dog jumped off the bank at me. I guess it was a friendly dog because he only jumped on my chest. It was so dark I couldn’t even see and it scared me beyond the edge of my life, even when I realized it was only a dog.

My father had two families. His first wife died, leaving him with four children who of course were much older than we were. My oldest half-sister had a boy named Everett Grade who owned a guitar. I was around 7 or 9 at the time. I wanted the guitar and he wanted a dollar for it. I had only ninety-eight cents, so I gave that to him. To this day I probably owe him the two pennies. I think he’d ordered the guitar from Sears or some other catalog company. Anyway, I just sat down and learned to play the thing. I could already sing from the day I was born. I never had a music lesson in my life. My daddy tried to teach me the notes – like do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do. He’d show them to me in a song book and say “Son, here it is.” And I’d say, “Yeah, but what is it?” It just always has been natural with my whole family. I had eight brothers and they were all singers. My mother wasn’t a professional singer and I guess she never sang anywhere other than inside our home. But she was a good singer, so it just came natural to the rest of us. My children too. I have three boys; the middle boy doesn’t sing very much, but the others do. And all three play music for their own enjoyment.

I had a cousin by the name of Dulcie Sauceman who also learned to play guitar. We started playing at ice-cream suppers and talent shows and such. We won every competition we played in, and it thrilled me, of course. Our pastor, who was pastor of the Wittenburg church and four or five others, used to take us from one church to the other to sing.

Around that time I was listening to a program on my uncle’s radio from Asheville, North Carolina called the Farm and Home Hour. Jack and Curly Shelton (not the better known Shelton Brothers of Texas) were on the program. After they went into the service their family moved close to ours. Curly was eventually discharged and it was said that he had TB. Some way or other Jack and I got acquainted. We started singing together; he played mandolin and I played guitar. We started doing shows at local schoolhouses. One night, after we finished a show, a fellow by the name of Uncle Dud Watson, the man who made “Kentucky Waltz” famous, offered us a job.

RKS: Was this before Monroe recorded “Kentucky Waltz?”

As far as I know, possibly so. This was probably around 1941. We started working at WISE in Asheville. We stayed for quite awhile until Curly Shelton and I decided to form a group. We did, and left WISE for WHKY in Hickory, North Carolina.

RKS: Who else was in the band at WISE?

Well, Uncle Dud played the guitar, and Curley played the mandolin. I don’t remember who the rest were, but there was a fiddle and banjo. When Curley and I went to Hickory the war was on and you couldn’t get any gasoline without ration stamps. We stayed in Hickory for quite a while but couldn’t do any good. I was the only one with an automobile and the tires were nearly worn out, but we finally got enough gasoline and drove from Hickory to Knoxville for an audition. This included me, Curley Shelton, a boy named Price Honeycutt who played steel and a fiddler named Rusty Hall, who was related to Roy Hall. The audition was successful and we went to work with Lowell Blanchard and the Mid-day Merry-Go-Round in 1944.

Not long after that I was called for a physical examination for the service. Supposedly they’d send you home for 21 days before you were called. But in my case it was a year before they called me back. So we went back to Asheville to the Farm and Home Hour on WWNC. Curley Shelton and I joined up with Tom Millard (who was also known as “Snowball” and had been a comedian with Bill Monroe on the Grand Ole Opry). The group was known as Tom Millard and the Blue Ridge Hillbillies. I worked in that band for a long while, at one time or another with Red Rector, my brother, Red Smiley (who was playing mandolin in those days), fiddlers Benny Simms, and Jimmy Lunsford, and Willie Carver, a fine all-around musician who played bass, electric steel and mandolin. I think Hoke Jenkins was in the act too, playing banjo. Hoke’s now dead but he worked for me a few years later in Bristol.

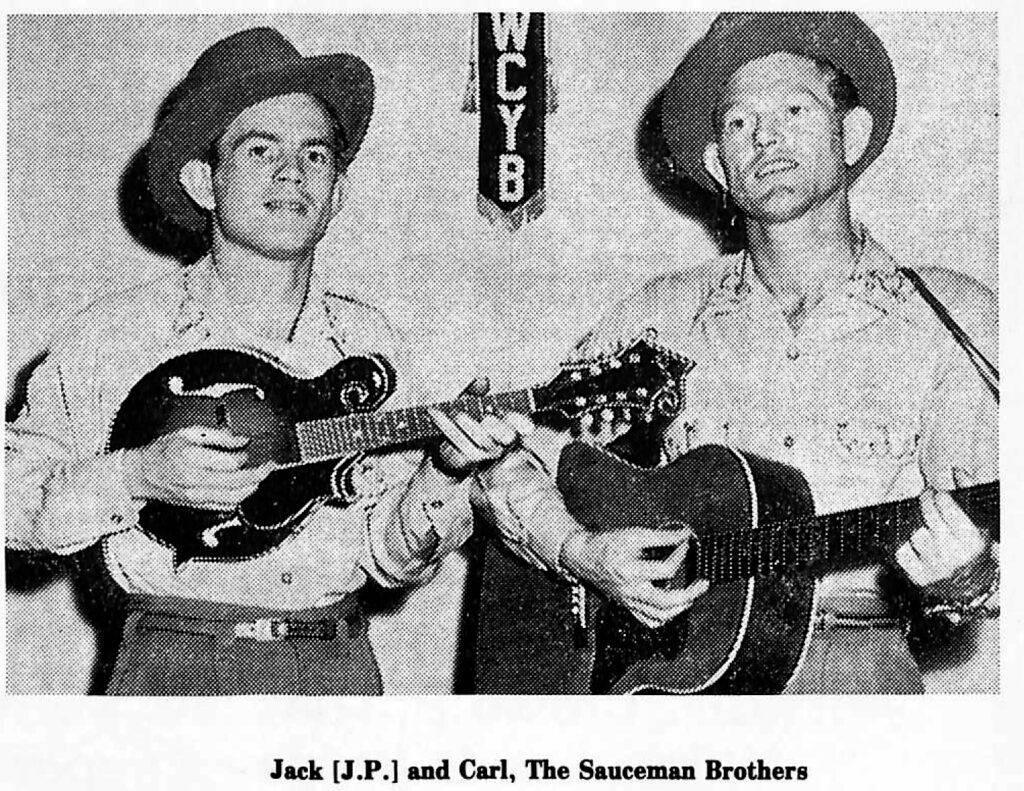

Regarding my brother, late in ’44 we needed somebody to help out with the singing. So we went all the way home from Asheville, arriving around midnight. I went in and told my daddy I wanted to get J.P. to help us out – J.P. was only 12 or 14 at the time. My daddy said, “I’ve thought for awhile this might happen. Well, you can take him if you’ll take care of him.” And I took care of him for several years, and I do mean take care of him. We’d go out and do a show and split the money up equally. I’d go back to our room and go to bed and the other boys would go out carousing. Next morning we’d go to the restaurant. I’d order and my brother would sit there and not say anything. I’d ask him, “Son, you’re not going to eat?” “No, I don’t want anything.” “Well, you got any money?” “Yeah, I got money.” “Well let me see it…” Then come to find out he’d lost it all the night before. He became responsible in later years and could probably buy me now for what I’d like to be worth.

From Asheville I was finally drafted into the Navy and went overseas. This was at the beginning of 1945 – I got out in 1946, a few days short of two years. While I was overseas I played with a group including Rudy Rymer and Jim Wright from Texas. I played a little bass fiddle with the base orchestra and sang “Only A Paper Moon” and stuff like that.

After I came home I went back to work in Asheville for a while with Tom Millard and my brother which is when Red Smiley was playing with the band. Around the middle of 1946 J.P. and I were offered a job in our home town to open a brand new radio station. We took Benny Simms with us and got a fellow named Thomas Martin from Virginia to play the banjo. Tiny Day had just gotten out of the Marine Corps and had a solo program. We merged, so to speak, took him into the band and then got our youngest sister Imogene. We stayed there for about two years, working shows all over. Imogene plays guitar and a little bass fiddle. Tiny plays bass fiddle and guitar too.

In 1948 J.P. and I left to work for Cas Walker on WROL in Knoxville. Tiny and my sister Imogene got married and stayed behind, so in Knoxville we formed a new band. We got Junior Huskey on bass fiddle, Ralph Mayo on fiddle and Wiley Birchfield on banjo. After a while Joe Stuart joined on mandolin and Tater Tate replaced Mayo. For a while Carl Smith worked for us. He came up from Georgia somewhere where he’d been working with Jim and Jesse and Hoke Jenkins. He was out of a job and came back to his home, about twenty miles from Knoxville. Archie Campbell had put together the Dinner Bell program at WROL, in the same time slot as the Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round which featured Chet Atkins, Homer and Jethro, the Carter Family and others. The Bailey Brothers were on the same show with us. They always worked for Cas Walker – never did work the Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round. Anyway, we were working the 5:30 a.m. show for Cas Walker and with Archie Campbell at noon, which presented a problem for Carl (Smith), who lived twenty miles out in the country. For instance if we made an appearance and didn’t get back until 3 a.m. he would have to drive home and be back by 5:30, which was too much for him. So Carl Butler came along and wanted a job. Archie Campbell preferred Carl Smith to Carl Butler, so he suggested that I take Butler and he would take Smith, who then wouldn’t have to work nights, just do solos on the noontime show. Meantime Carl Smith had been negotiating with Troy Martin at Columbia. I knew he was going to get a contract and leave anyway so I was pleased with the deal because Butler was more of a bluegrass man than Smith. So Carl Smith went to the Grand Ole Opry – I took him there in my car the very first night. Soon after that Butler went with Capitol Records and we kind of drifted apart. But while he was with us we recorded two gospel songs for Rich-R-Tone, “I’ll Be No Stranger There” and “Hallelujah We Shall Rise” with Carl singing lead, me singing tenor, Tater Tate baritone and Joe Stuart singing bass. Carl Butler worked for us about two years.

In 1949 Joe Stuart, J.P. and I went to Detroit for a few months to play in the clubs. The York Brothers had left the Opry and were doing well in some club here. Chubby Wise was with them and word got back from him. So we just drifted up there and decided we’d make our fortune and come home. But soon I said to myself, “Lord, let me live long enough to get out of these clubs and I’ll never go back.” While we were there our mother passed away, so we came home to Greenville for the funeral. While we were there we heard about a job on the Bristol Farm and Fun Hour. We went for an audition and Lester Flatt gave us the highest recommendation possible for a bluegrass outfit. We got the job after returning to Detroit to finish out our business there.

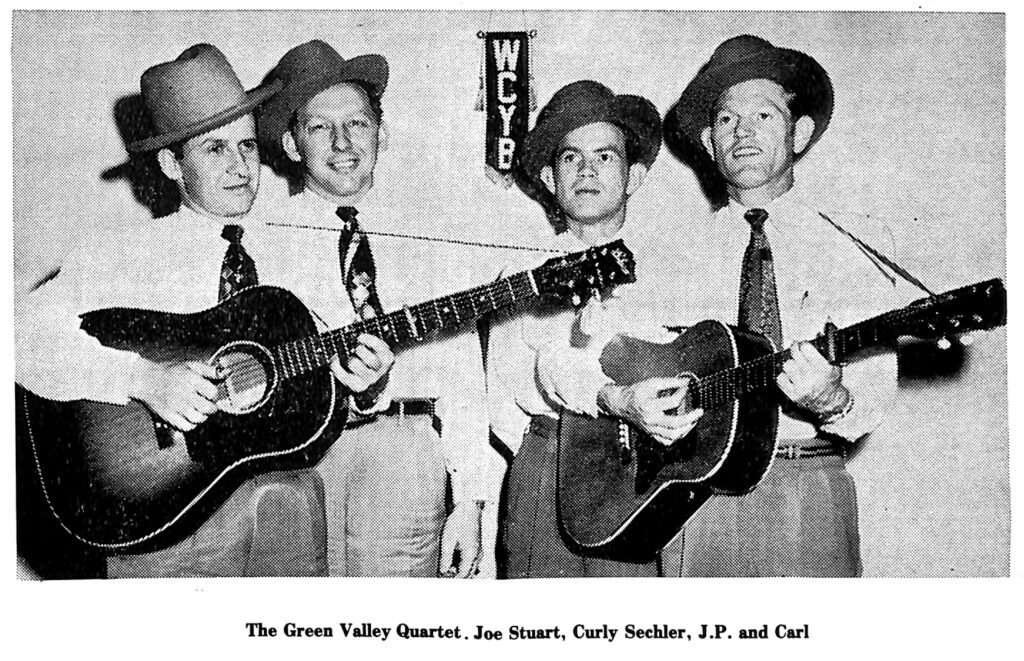

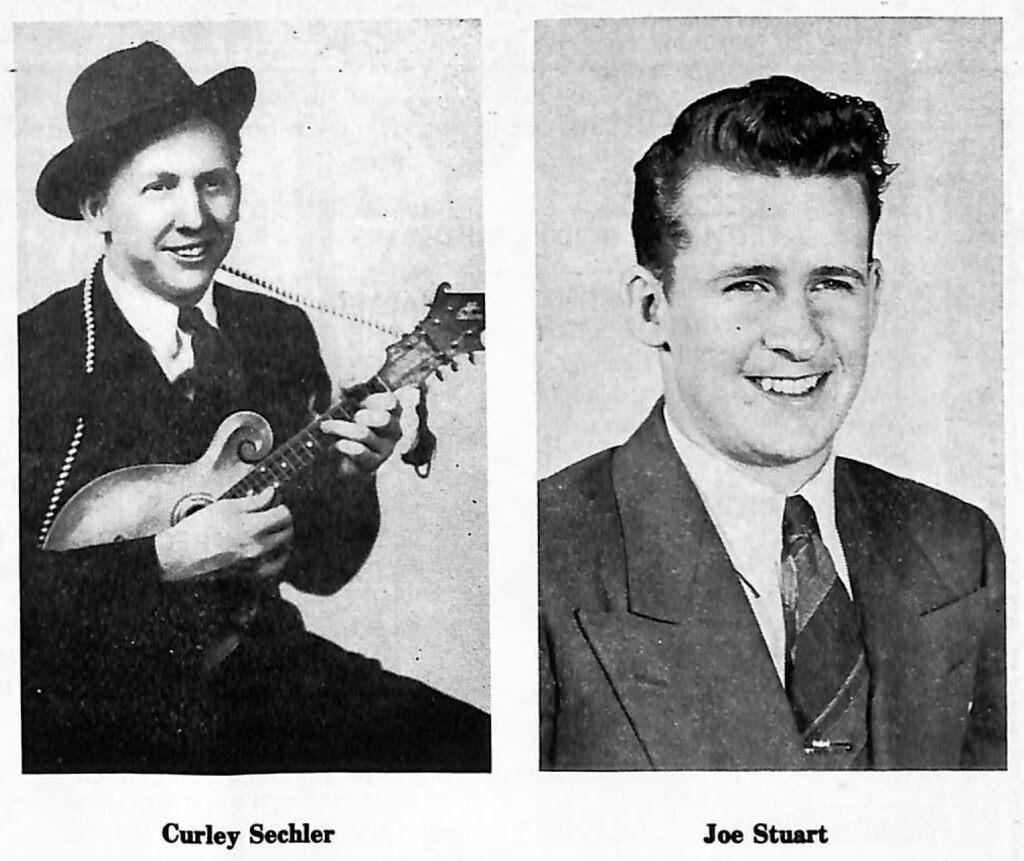

We went to work on WCYB around the end of 1949 with Joe Stuart (guitar), Larry Richardson (banjo), Tater Tate (fiddle), Curley Sechler (mandolin) and, for a while, Arville Richardson on fiddle – his brother played the bass fiddle.

I came to Carrollton, Alabama in the first part of 1952. At the same time I lost my father and signed a contract with Capitol. Jimmie Skinner, through his manager Lou Epstein, negotiated the contract. But I had to return home after my father’s death and lost a month in getting to Alabama. Meanwhile Joe Stuart went with the Bailey Brothers and Curley Sechler joined the Stanleys, and Larry Richardson went with Bill Monroe and tried to talk to me into coming with him. But I already had made the deal in Alabama so I went on, taking a jack-let band with me. I don’t want to discredit anybody, but Don McHan was the only good man I brought with me, a good banjo man who actually can play all instruments. For a while we had Tater Tate, Larry Richardson, Joe Stuart and Curley Sechler back with us. My brother was in the service and then he came back with us.

Finally, after a number of changes, I wound up with Jimmy Brock, a great fiddle player, Monroe Fields did the tenor; he played the mandolin and was a great singer and songwriter. We had Fred Richardson from Ervin, Tennessee (no relation to Larry), one of the greatest banjo pickers I’ve ever known. When Fred went in the service we replaced him for awhile with Buddy Rose. Fred came out and went with Jim and Jesse over in Georgia for a while. But he didn’t like it there. He wrote me a letter and said “It’s so hot over here I saw a dog chasing a rabbit and they were both walking.” And I got him back to Alabama. We had two young fellows we kept to sing those solo songs for the young folks, Bill Wilburn and Dickie Mauldin.

RKS: When you left Bristol for Alabama where there wasn’t much in the way of bluegrass, how did people react?

Well, you could say they were absolutely flabbergasted and that would be an understatement. The man who owned the radio station had a chain of movie houses and we started doing stage shows. We’d get up there and those boys would pick their hearts out, and they’d just look at you – nobody’d raise a hand. My wife makes friends very quickly and in a few days she’d gotten acquainted with a few neighbors. She got them to come to the theater and sit in the front row where they acted kind of like cheerleaders. So after a few shows people began to realize we were doing something, but they hadn’t figured out what it was. For one thing, they had never seen a banjo. But with my wife and her friends acting as cheer leaders they started reacting and it got to the place where we’d get a reaction to a solo, a five-string banjo tune or almost anything we did.

RKS: In this band, who was singing what part?

J.P. sang lead, I sang tenor and Monroe Fields would sing the high tenor (baritone). Monroe would take the electric guitar on Saturday night and, if they wanted rock and roll, we could do it. If they wanted Eddy Arnold, Conway Twitty or George Jones we could do it. Monroe could tone his voice down and sound exactly like George Jones. Ask George himself if you don’t believe me. Of course we did bluegrass too, but I have to give this band credit they were versatile.

RKS: Who took care of picking your material and deciding how you would do it?

Well, in the early years no one took care of anything like that. If there was a song you liked you learned it and sang it, or we would rearrange it to fit us. If it was a pop or country and western song and we thought it was good, we might speed it up and add harmony to make bluegrass out of it. That was easy, because all of us could sing the different parts.

In those days package shows were coming in. There was always somebody calling me to book double shows with them – Lester and Earl, Benny Martin, the Carlisles, Lonzo and Oscar and others. But we didn’t take a back seat to any of them. This was a talented group of musicians. We could all turn our backs to each other and know exactly what each other was doing. We were busy too. There were three television shows a week and two live radio shows a day. I did a disc jockey show every day and we had weekly TV shows from WLAC in Nashville which we’d go up and tape every three months. There was a show every night at some school or theater. We did a dance every Saturday night at the National Guard Armory when Sparkplug (Fred Richardson) would lay his banjo down for a set of drums, and he was fantastic on the drums. And we filled that big armory every Saturday night.

I quit at midnight, December 31, 1962. I had given the fellows two months notice. The job lasted until 1 a.m. but I got off the stage at midnight, and they finished by themselves. That ended my career in show business. The reason was my youngest boy. He only lived to be 13 and he was an invalid from birth. Everything happened to him – four major operations, amputations of both his legs and more. Out of those thirteen years he was home for maybe two or three; he spent the rest of his life in the hospital. I would have to walk off and leave him and it was almost more than my wife could handle, so it was too much for me to continue on the road. After I quit he lasted another year and a half. After that they came to me and wanted me to go into show business again, but I was finding out that I had a better life than I had known before. I’m owner and general manager of WSLG radio in Gonzales, Louisiana and doing some disc jockey work here. I’m satisfied to do four or five shows a year – regular commitments I’ve had every year for a while. I go back to Carrolton for their radio station’s anniversary every year, to the Old South Jamboree in Walker (Louisiana) and to three or four bluegrass festivals every year – and if someone comes along wanting to pick, brother, I’ll be ready to pick.

RECORDINGS

J.P.’s country record (on Rich-R-Tone) was our first effort. I can’t think of the name of it; it was an Eddy Arnold type solo. Hobe Stanton (owner of Rich-R- Tone) had a guy on that label named Buffalo Johnson, who had a good dance band with a steel guitar man named Toby Wheeler and Walter Haynes played the fiddle. So Hobe took them into the studio with us to try for an Eddy Arnold-style song. It was his idea.

RKS: Did it sell well?

To my knowledge, no, right afterwards, J.P. and I went back to do some “corn” as we call it. That was “Pretty Polly” and “Little Birdie.” I forget if it was Benny Simms, Shorty Bastin or Fuzzy Chamberlain on fiddle, but Wiley Birchfield played the banjo, J.P. played mandolin and I played guitar. Actually, the fiddle probably was Fuzzy Chamberlain, a boy from Morristown, Tennessee who later went to California.

About this time Hobe started recording the Stanley Brothers, and they were hot! I know because I went on the road part-time selling records for Hobe, who also had the distributorship for Mercury, so I was a salesman for both labels. Every time I walked into a record store and they found out I was selling Rich-R-Tone, they’d holler for me to bring them a load of Stanley Brothers records. Hobe would know that if I hadn’t been to a place for a week that they’d be out of Stanley Brothers, so I’d take a carload with me, deliver them and bring the money back to him. It was kind of embarrassing when they’d order 500 Stanley Brothers and maybe three of yours. Which may be why Hobe got the idea for us to record that “corn.”

One day a salesman for RCA walked into a record store in Harlan, Kentucky with his supervisor. The salesman asked who the biggest selling artist was, thinking the answer would be Eddy Arnold. When the dealer said it was the Stanley Brothers, the supervisor reared back like a judge and said who are the Stanley Brothers. The reply was that they were the hottest thing in the country. So RCA negotiated with the Stanley Brothers to try and sign them, but Carter Stanley was a very independent individual. RCA wanted them to come to Nashville, but Carter told them he didn’t have time, and if they wanted to see him they could come to Bristol.

Our Mercury records were made while we were in Greenville in 1947. We made them for Murray Nash, who is out of show business now. We made four records and I think three were released. I wish I knew what happened to the other one. Thomas Martin, Tiny Day and our sister Imogene were on those with us.

Carl Butler was with us when he signed his first record contract. We furnished the music for his first session. We did it at WROL in Knoxville, and I believe Fred Rose and Leroy Martin were there. We added a Dobro player to the band, a fellow named Speedy Krise, and I remember it broke Carl’s heart because they said his guitar playing was too loud and wouldn’t let him play. I played the guitar and we didn’t use a banjo. Tater Tate and Junior Huskey were there, and possibly Joe Stuart.

When I came to Alabama we had signed with Capitol as the Sauceman Brothers, but my brother had to go into the service; he was in the Marine Corps during that time. That’s when I got Don McHan to go with me. We had one record that sold really well, a patriotic song called “Wrap My Body In Old Glory” written by Arthur Q. Smith – don’t confuse him with Arthur Guitar Boogie Smith or Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith. Arthur Q. Smith wrote so many good songs – “Wedding Bells,” “If Teardrops Were Pennies And Heartaches Were Gold” and many like that, but he sold them all. He tried to sell me “Wrap My Body In Old Glory” but I said, “No, Arthur, I’m gonna do you a favor and record it.” It’s one of the few songs ever recorded with his name on it. I was with Carl Butler when he bought “If Teardrops Were Pennies” and paid twenty dollars for it. I had the chance to buy “Wedding Bells” myself but turned it down. He’d take the twenty and go straight to a honky-tonk. He died broke.

Two of the best songs we ever did were on the Republic label – “I’ll Be An Angel Too” and “A White Cross Marks The Grave.” Don McHan wrote those songs and sung them on the record. They were really professional. After that we made a record for Troy Martin. I don’t remember the label, but I do remember that only a few copies were ever sold around Georgia. One of the songs was “Oh, Boy, I Love Her.” The guy who owned the label was locked up just after we recorded it.

Monroe Fields and I wrote it, and it was covered immediately by Johnnie and Jack. Troy Martin negotiated the session for us, and we cut it in the RCA studios in Nashville. It was arranged that our record and Johnnie and Jack’s were to be released at the same time. We announced it on the air and just about wore our copy out playing it, expecting that more copies would arrive. But they never did.

After that a guy came to me who had a girl friend whose husband had died and left her a lot of money, and they wanted to start a label. At first he wanted my band to back him but I said we weren’t for hire – we had a different sound which I wanted to keep for myself? Then he suggested we record for him and I told him if he had the money we had the time. His label was in Florence, Alabama and called “N”. We did an extended play gospel thing, and a tune called “Whoo-ah” that Monroe Fields and I wrote Mr. Neal (that’s what the N stood for) didn’t want a banjo on it, so he got Kelso Hurston and Peanuts Montgomery to play electric guitars.

That record went to number two on Ralph Emery’s (WSM) hit parade and it lasted there for seventeen weeks. It was our best-selling record by far. In Meridan, Mississippi one record shop was selling two of our records for every one of Elvis Presley’s – and that was when Elvis was hot! Mercury, Decca and others were begging Neal to sell the master. Of course our publisher, James Joiner of Tune in Florence, Alabama was begging him to sell it too. We were able to talk him into letting Decca have it. They were going to pay him $6,000 for the master and seven cents a record. Owen Bradley grabbed the record and flew to New York with it, and was told that if he could get it on the market in ten days he could do it.

Bradley called the publishing company, but they couldn’t find Neal. I went looking for him and found him at a little radio station over in Mississippi. He called Decca and the first thing they wanted to know was if it was a union session. He said it was. He agreed to run up to Memphis and register the session at Decca’s expense. After three days he hadn’t shown up and they called me again. I told them that he’d confirmed that he’d do it but you know he never did. Then Bradley called James Joiner and asked if our band was union. He said he didn’t know but he didn’t think we were. So Bradley said it would take too long and to just forget it. I saw Bradley again a couple of months later and he asked me why I wasn’t in the union, as many years as I’d been in show business? I was surprised at that, and told him that I’d joined the musicians’ union in Knoxville in the early 1940s, and showed him my card. He invited me to come to Nashville with some good material. But I never went. By the late fifties we had all the work we could handle, records or no records, and I was pretty disgusted with the whole business by then anyway.

A little later, in the early 1960s, we made some records for Pappy Dailey’s “D” label. The best known one was “Please Be My Love.” Monroe played take-off guitar on it – just a plain capoed flat-top, no electricity. It sold well as a single, then went into a “D” all-star album, and still later was cut on United Artists by George Jones and Melba Montgomery. They did it as a single and it was in an album too. Then Jim and Jesse recorded it, and so did somebody in Michigan. That song’s still playing, and we’ve gotten quite a lot of money from it.

BOOKINGS Our first booking agent was Drexel Day, Tiny’s father, then Tiny booked for us himself, while we were in Knoxville and Bristol. For a while when we were still in Knoxville, a fellow named Charlie Lamb worked for us, who later started the “Music Reporter” in Nashville. Kentucky Slim was our comedian for some time in Knoxville and he booked for us too. After we went to Alabama, Fred Richardson and I both did booking at different times, and then we hired a boy from North Carolina named Cecil Davis.

STAGE WORK J.P. is a good musician but he has always been the backward one on stage. I did all the MC work and generally was the front man. He can beat me playing and singing ten to one, but he can’t get on a stage and talk to people. One time we had to practically tie him and Tiny Day to the microphone to record. They’d both back up too quick and cut a word off. But I was always the forward one. The bigger the crowd the better I liked it. I’d go out there and look them smack in the eye and talk to them. That’s the only way you can feel out your audience and find out what they want. If you look then in the eye and you’re doing something they don’t enjoy you can tell it. I love to entertain people. I get wrapped up in my music and feel it from the bottom when I sing. But you still have to find out what a crowd likes if you expect to have them back again – you have to know you’re doing something they like. Like you should know when it’s time to liven up a program. I’ve stood up there and sung those old gospel songs and watched those old mothers and daddies with tears rolling down their cheeks. You can feel when they’ve cried their hearts out and had enough. Then it’s time to change, to tell a joke and make them feel happy again. But you have to look at your audience and feel them – for me this is entertainment.

JOE STUART AND CURLY SECHLER At one time Joe Stuart was the greatest mandolin player there was. Something else he’ll never get credit for is that finger-style guitar that Earl Scruggs used. Joe Stuart is the man who started that. If you don’t believe me, listen to the quartet record we made for Rich-R-Tone. Joe had an old flat-top Gibson. He wore a hole through it near the bridge and we had to fill it with wood. Curley was with us at the same time; Joe would play bass when Curley would play guitar. He can play the finest rhythm you’d ever want in a bluegrass band. He worked with me for about two years the first time, and then again for a year in Alabama before going back with Lester and Earl.

Man, you don’t know how it makes me feel when I think that everybody who has worked with me, I could get back tonight if I could afford them. That was the way I treated them; I never mistreated anybody.

BLUEGRASS. I was playing bluegrass long before I ever heard the word. In those days you just called it all country music or hillbilly music. Then the Grand Ole Opry wanted to get away from the word hillbilly in the early 1950s. The guys who didn’t want to be labeled hillbilly started calling it country-western and they separated that from bluegrass, and they quit calling it hillbilly altogether. When Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs left Bill Monroe and went off on their own – that’s when the term probably came about. In all fairness, when Lester and Earl started we’d been in the business for years, though I’d never thought of myself as a bluegrass entertainer. Our name was the Hillbilly Ramblers, and Cas Walker made us change it to the Green Valley Boys because he didn’t like the word. And today everything is either country- western or bluegrass.

VIDEO TAPES This boy from Columbus, Mississippi went to Nashville to work for WLAC around 1959. You know those syndicated gospel shows that go out all over the country? WLAC got an idea to do a country show the same way. So this boy recommended us for the show. The show was Eddie Hill’s, and he would come on and say “Well, it’s time for us to get a little music going. How about ol’ Carl Sauceman and the Green Valley Boys singing one for us?” and so on. We did a bunch of film numbers like that for him which he used for several years. And they’d put shows together and send them all over the country – somebody even told me they’d seen us in Canada!VIDEO TAPES This boy from Columbus, Mississippi went to Nashville to work for WLAC around 1959. You know those syndicated gospel shows that go out all over the country? WLAC got an idea to do a country show the same way. So this boy recommended us for the show. The show was Eddie Hill’s, and he would come on and say “Well, it’s time for us to get a little music going. How about ol’ Carl Sauceman and the Green Valley Boys singing one for us?” and so on. We did a bunch of film numbers like that for him which he used for several years. And they’d put shows together and send them all over the country – somebody even told me they’d seen us in Canada!