Home > Articles > The Archives > Butch Robins

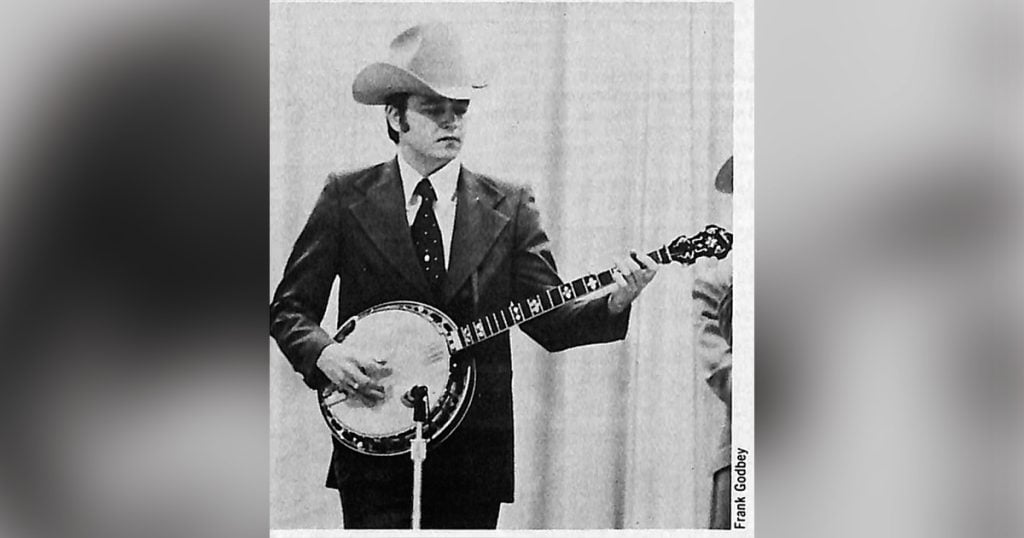

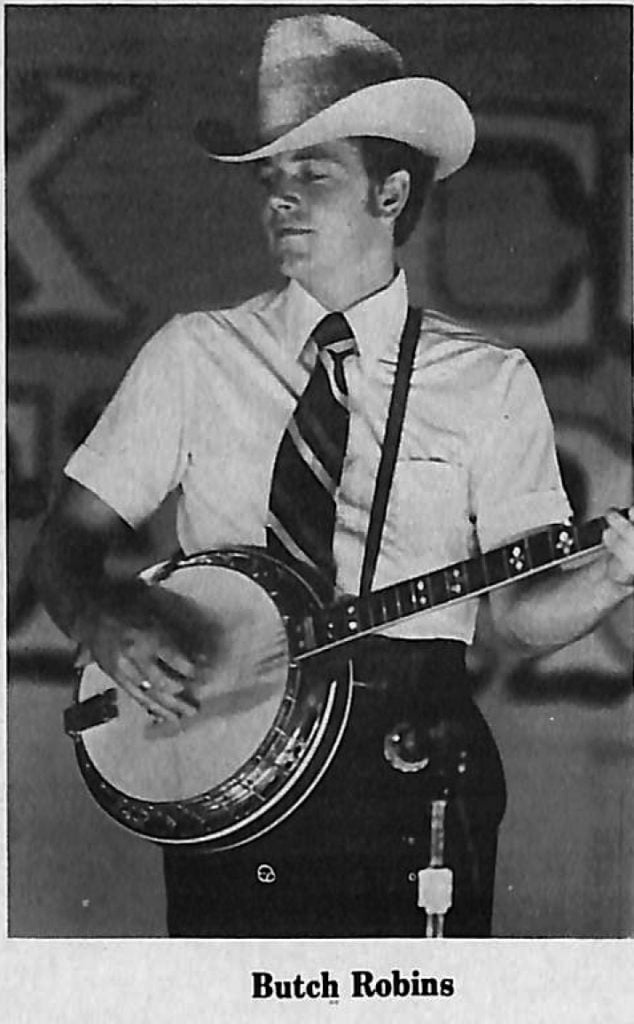

Butch Robins

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1979, Volume 13, Number 11

In October of 1977, when Butch visited Los Angeles as a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, we first discussed the idea of the following article. During the winter months we corresponded and when I was offered a job on the road this past summer of 1978 I warned Butch that I’d be looking for him, hoping to pick his brain as well as my bass.

It was at the Grand Ole Opry this past August where Butch and I again met face-to-face. He invited me to come out and stay with him if I had a few days off, and it happened that I was playing about a hundred miles from his place the next night. After passing Butch’s on the way to work I doubled back to the small town near Roanoke, Virginia, where Butch and his father, Calvin, have made their homes since 1964.

After dinner with Butch, his wife and six-year-old son and picking up Ed (“Tut”) Chumbley, we embarked on the “big, oh-boy tour of town.” I asked Butch if he was well-known around there. “I’m not known around here at all,” he replied, explaining that he was a good, though not exceptional student and athlete in high school, never got into any trouble and anything he did musically was out-of- town, so there was no reason for him to attract much attention there.

“I’m getting more and more attached to this place these days. There are not many folks here, not a lot of money in this area. It just seems that in comparison to most of the places I’ve had to work and had to be in this country, people in this area get carried away with themselves less than they do anywhere else. There are people I went to school with who are involved in things that are pertinent to this area; I’m glad to see that. I’m glad to see that folks think enough about the place where they were raised to stay there and try to keep it the way it was when they were young. I think up here is a pretty decent place for kids: There’s a lot of recreational area, a lot of sports around here for young people, institutions of higher learning. Most of this area around here is pretty up-to-date on things. Anyhow, I like it here. This is my little hole to crawl into and get away when I lose my picture of where I am.”

This small Virginia town was the last stop for the Robins family after a series of moves which began in 1953, when Calvin accepted a position with the Tennessee Valley Authority which took them to Alabama, Kentucky and Eastern Tennessee before they settled in North Carolina in 1958. Before they moved to Virginia, Butch had discovered the five-string banjo.

“An old guy named Homer Israel taught me with the thumb, index finger, middle finger; one-two-three roll. My dad would sing and I’d play chords behind him and eventually I’d learn to play melody lines, just play ’em straight out of a chord position. I could catch up on changes quickly and that enabled me to play with some local musicians, sort of compliment what they were doing and play some back-up. It just sort of developed. I never listened to anybody that much. I had the ‘Foggy Mountain Banjo’ album and I had a bunch of Don Reno’s albums. I listened to Reno probably more than anybody else who played.

“I was really lucky when I was starting out. I would always be able to be around when somebody like Don Reno or Carter Stanley would be around. Somehow I’d wind up playing tunes with the bands and I got to be relatively good friends with the folks.

“When I started following professional bluegrass acts the only people making money at it to where they could call themselves professional were the Stanley Brothers, Reno and Smiley, Flatt and Scruggs, Jimmy Martin and Bill Monroe. I was young and I asked questions. If I would have a question about being a professional musician—-more than just a picker-—I’d ask the professionals how I could get by and have as little friction as possible and they helped me.

“One night over here in Floyd the Stanley Brothers came through and I played the third set of a square dance. They were joking with Carter and I got a really warm feeling from the man. I liked him; I didn’t get to know him well enough but I just got a real warm feeling from being able to stand there and pick with him. I got exposed to Jimmy Martin quite a bit that Christmas weekend up at a friend’s house in Bristol. I spent three or four days there and Jimmy kept hammerin’ in my head how to play melodies on ‘Will You Be Lovin’ Another Man’ and ‘My Little Georgia Rose’ without playing either Reno cliches or Scruggs cliches in them. He was really nice to me that weekend. He helped me a lot with my playing. I got to know the Osborne Brothers later on and Sonny has become one of the better friends I have in this business. Among all his witticisms, he has given me really good professional advice. He’s one of my all-time favorite banjo pickers, as well as being an extremely decent person. There’s a side of him that’s fantastic and he’ll give his time to a young man. Lewis Phillips, the youngest Lewis Family member, idolizes Sonny and there’s good reason, because Sonny is real good with kids. He really encourages his children in sports and outdoor activities.

“Six months before I got out of the Army, Charlie Moore hired me which got me on some festivals and got me back with those old-timers, like Red Smiley and Mac Wiseman. I got to see the Osborne Brothers occasionally and the Lewis Family. They’re good folks. They’re folks I know who were friendly to me when I was a child and I’ve tried to grow up doing the same things they do and I have a good time around all of them. I especially enjoy the older, hard-core people. I guess I can appreciate them more because they’ve put down more of a tangible product and I can look at their music as it’s developed. The way Jim and Jesse’s music has developed, for instance: they’ve gone on all kinds of musical tangents. Now they’re back to basically the sound they had with Allen Shelton and Jimmy Buchanan, and they’re putting out some good music. The Osborne Brothers, to watch them go through their country music trip and be successful at it—-hit on ‘Rocky Top’ and put real up-tempo country music behind that and having Sonny playin’ steel licks on the banjo. He’s great at it.

“When I quit Charlie Moore I went down to Nashville, despite being told by various people that there was nothing for me in Nashville and I would starve, but it was the only place I could go then with enough of a market for what I did where, hopefully, I could support it. I convinced Vic Jordan that I could play bass because I knew the fingerboard of the bass, really the fingerboard of the bottom four strings on a guitar, with no idea of how the instrument should voice itself to be part of the music. I played on Vic Jordan’s record which subsequently got me on Jesse McReynolds’ mandolin album—and I couldn’t play the bass! Anyhow, I got through that and when Keith (McReynolds) was having exams at school, Jim and Jesse asked me to go out on the road with them for a weekend and I said sure. So old brilliant me, I wrote out chord sheets on everything from ‘Hard-Hearted’ to ‘Voice Of My Darlin’ and I had it all written down to where every note I was supposed to play was written down on these two pieces of paper. I spent a whole day riding up here to Virginia to do the first job and when I put the papers on the floor I found out I couldn’t read ’em. I couldn’t see; I had written too small! A disaster. I swore I would never play bass again.

“Of course, I did wind up playin’ bass for Sam (Bush) and the boys—the New Grass Revival. That was the best time I ever had in my life, as far as music. I was introduced to a super-musician on a daily basis, instead of just getting together here and there. Three super-musicians, actually, each one unique and very good at what he does. I learned to think in that band in a way that prepared me for this job I have now.

“What finally happened was what happened in the first place: I didn’t belong in a band playing bass. They needed a bass player who had spent as many years on his instrument as they had on theirs, not someone who had just picked up one. I was fifteen years behind that band.”

Over a three-day period we taped nearly eight hours of interview material either at Butch’s house, at Tut’s house or on a boat on nearby Claytor Lake. Whether at a kitchen table, between turns on water skis or on the lakeshore, whenever we talked about music the conversation would nearly always drift back to one subject: Bill Monroe.

“He’s the central figure in my career right now. In five years or ten years when I feel secure in my job—-if I ever do—-when I can sort of reflect on this thing and take it all in perspective I’ll probably have different views and different attitudes. Some of the things that happened earlier than this will probably take on more importance than they do at this time, but right now I’m hung in the middle of it. I’m caught in the situation of where the music I love comes from.

“I’ve always been drawn to the energy of Monroe’s music, real ultra-high-energy acoustic music. Bluegrass hits you. It’s like blues music; it hits you in a whole bunch of places. It hits you on the beat, it hits you on the back-beat, it hits you on the quarters, it hits you anywhere Bill Monroe can hear to play the rhythm to it, and he can play just about anywhere you can think of to play-—and it will be right! The syncopations and everything he does come in extremely funny places sometimes and he’ll have to do one ten or fifteen times before you can hear it. Some of them are so subtle that when you start getting into it you think you’re hearing things.

“Bluegrass is Bill Monroe. It started there and it stops there. It’s his rhythm chop on the mandolin and it’s the power of his voice, the range of his voice, the range of the lead lines he plays on the mandolin. There are a lot of people who have been in it who have added to it, but that’s all they’ve done. They weren’t it when they got there and they weren’t it when they left. They added lead lines, solo breaks, but the thing that made it bluegrass nobody added. Monroe brought that and he’ll take it home with him. He plays with power. He gives every tune a different face, a different color, a different mood and that’s extremely hard to do, especially in these little two-and-a-half or three- minute energy blasts—and they are intense little blasts. It’s the most exciting rhythm I’ve ever played to by far. I used to try to define it as white country people’s blues music, but it’s more than that. It touches people in rock—from Elvis Presley recording ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’ all the way to the Eagles who have turned around and used the banjo as a lead instrument out front—and it came courtesy of Bill Monroe. If it hadn’t been for him there would have been no such thing as someone playing a banjo. He was the vehicle for Earl Scruggs. Where else in 1945 could Earl Scuggs have gotten the mass audience he got with Bill Monroe?

“It’s a cross of the folkies and the jazz and the blues people ’cause it’s down-to-earth music, or at least it’s always been billed that way, so the folkies get into it. The blues people get into it because it’s real high-energy country blues music. Jazz people get into it because it has real complex lines. The melody lines themselves are complex pieces of music in bluegrass, or what I define as bluegrass, Monroe’s music.”

Though Butch is blazing new trails in bluegrass in his solo efforts, he draws heavily on the contributions of previous Blue Grass Boys in his playing when working with Monroe.

“How can you play a better break on ‘Molly and Tenbrooks’ than what Earl Scruggs played? I think it would be absolutely impossible. That break right there gave the banjo its role in bluegrass in the sense that it played the melody of the song. Like Rudy Lyle’s break on ‘White House Blues,’ or ‘Rawhide.’ I play a break on ‘Rawhide’ and I don’t even know if I do the notes even close to what he did but I really did like the sound he got out of that banjo, the way it just really cracked out and the simple notes. It’s just a simple, kickin’, full-speed-ahead break. Don Stover got a really nice sound out of his banjo on ‘A Falling Star’ and ‘Out In The Cold World.’ ‘Out In The Cold World’ is one tune I’ve never been able to play; that or ‘Little Joe,’ either one. ‘Little Joe’ is probably my favorite bluegrass song, but I cannot set the rhythm right on those two songs. I just absolutely can’t play ’em at all, but the breaks on the records were good.”

During the summer of ’78, Butch’s mind was also on finishing his second album, “Fragments Of My Imagination.” We discussed a test pressing (of the LP) which arrived the day I did. We played it a lot that week, and I was very impressed by Butch’s debut as a mandolinist and singer.

“Most of it is ‘up’ type music, even the slower-tempo things. That’s the direction I’ve seen. Now I’d like to be able to understand it and to be able to have that at my command as a musician, to write a sequence of notes which, if played in the proper way, would make people feel a certain way. I guess I stepped out-of-bounds more than I would have liked to at this point, but after all, that’s part of what the music I play now is made of. The music I want to come off a turntable is going to dance off there at you because it’s going to be alive. I got together with three or four old boys I know and we just went up there and had a good time, and we played a little bit of music too.

“I don’t think any of the music I played on the LP would go to a bluegrass market. If I wanted to exploit that market I wouldn’t have recorded but two of the tunes on there. I’d like to play to a bluegrass market but I don’t know if I can. I don’t know if that’s the kind of music I can write or not. When I learn to play adequately within the job I have right now maybe I’ll be able to write tunes in that idiom, but right now I can’t. I don’t have command of it. Right now the music I write is just like a child in elementary school or junior high school writing graffiti on the walls.

“ ‘Music In The Air’ was my little boy’s fourth birthday present. I wrote him a song because I didn’t have much else to give him at the time, and he likes it. He sings it. He really gets into singing with tapes. He’s got mine, got one by Kiss, one by Debby Boone—he’s dynamite on ‘You Light Up My Life.’

“It’s an album where I tried a whole lot of different approaches to music. It’s music I’ve never heard before; it’s just music. That’s all I can play at this point. Even the next album or two—the next one’s already written and the one beyond that is about halfway done—I’m just trying to make music that will lend credibility to me as a musician. It’s my sincere desire that I will be able to play music through forty or fifty years of my life and right now the music I’m making is rough sketches of what I’ll be doing later. I want a product that you can see develop over at least a forty-year span of time and right now I’m playing music I hear that comes out of musicians I’ve worked with. It’s going to take me a long time before I can write a tune that has a half-dozen different parts, or even three or four parts, where the timing changes drastically.

“In the end, it’s my sincere desire that my music will be an emotional experience for people—and that’s it. It would be a very gratifying experience if someone were to listen to me and copy my licks, but it doesn’t really matter to me. I’d rather see a couple in front of me dancing to music I made than for a banjo player to play me back one of my tunes. If the music out of my banjo can make people’s bodies move there’s something about it that’s conveying motion and that’s my aim. I’m not a technician; I’ve never had the hands to do it. I feel that I’m poorly coordinated compared to someone like Larry McNeely, Jimmy Arnold or Alan Munde. Those peoples’ hands do things my left hand can’t even imagine. I wish I could have had the dedication, the motivation to practice a lot when I was younger, but I didn’t.

“I like to make all my records different and make my banjo sound different on each record. It’s a new experience that way. In fact, I like to make my banjo sound different on each tune. I think about it and I want to be complete with it. I want the instruments to sound different yet I want them to sound good. If I use a phase-shifter on the mandolin to enhance it a little bit, I want it to sound just as good as that mandolin does when it’s purely acoustic, only in a different vein. I’ve got an extremely good engineer in Boston named John Nagy who does the bigger part of my records, either in his studio or him personally. John is consistent and a good guy to work with from an engineering standpoint; I like the way he does things.

Most of the setting I’ll be in throughout my career–where I’m leading the band—will be in a recorded setting; it won’t be a live band. I don’t think I’m capable of that.

“I told you a while ago about Earl Scruggs and how his playing when he went to work for Monroe just blew the top of my head off, and just about anyone into bluegrass will tell you the same thing. Turn around and ask them just how many times they were sittin’ down in the front row at the Grand Ole Opry. I wasn’t there and I’d say ninety percent of the people today weren’t there—but they’ve got the tapes. You can tell from those tapes that Earl Scruggs was blowin’ the top off the place. That banjo was alive; it cracked clean through a thousand miles of air. Any place a radio could pick that thing up it was just like you were sitting inside of it. That’s coming through on recorded tape and when you’re in a studio you’re dealing with recorded tape.

“There can be a setting in the mind of a musician where that feeling can be put over in a studio. One person who impressed me as much as or more than anyone else in being able to get people ‘up’ in a studio setting like that was Leon Russell. He really knows how to make musicians come alive for him in the coldest of settings. Norman Blake is one of the most fantastically ‘up’ session men who ever was. He could make people who weren’t familiar with the studio really relaxed and everyone would have a good time. He’s got a really fine way about him. As a producer I’d like to be able to do that. If I’ve got a group and they go in there and get cold. I’ll throw a party and be the host. If I can be a clown and fall over a microphone wire to loosen the tension when somebody’s having their discussion in the middle of the floor, that’s the capacity I’d like to be in. Unfortunately, pay for that kind of job is relatively low and it’s a very time-consuming thing. People are spending a lot of time in studios these days.”

For the last two years Butch has been finding relaxation racing go-carts, and accumulating an impressive collection of trophies in the process.

“They’re four-fifths-size go-carts. They have Wankle engines. On those tracks they’ve got them set to where top speed is only about seventy miles an hour. If they’re opened up ungoverned they’d do a hundred and ten, hundred and twenty, and they’ll get you there about as quick, too.

“I appreciate the man who can wield an axe or drive a tractor and all that. I appreciate the fact that some of them can go out and just hack away for ten or twelve hours. I’ve done a little bit of work in my life, enough to know I don’t like it, but it ain’t a durn bit harder than sittin’ in a car and driving for ten or twelve hours—or fifteen. In order to survive you have to be pretty good at it.”

Butch is proud of his instruments, a 1941 Martin Herringbone D-28 guitar, the prototype five-string Dobro he used on “Hank Wilson’s Back” and “Forty Years Late” and a number of banjos including a custom Tennessee top-tension and a Fender Concertone. He is proudest of all of his latest acquisition, a 1934 Gibson RB-4 flathead.

“It’s original and immaculate. It’s got a good range, a good, full sound and a lot of body. When you get to these old instruments they all sound good yet they’re all different. One thing you can be guaranteed: If you’ve got the original bill of goods, you’ve got a good-sounding instrument. You don’t have to ask and you don’t have to wonder about it. You don’t have to think your ears are playing tricks on you on a bad day. Some days my banjo sounds terrible to me, but I know it’s all right. It’s me that’s the problem.

We talked about young musicians, some of his favorites being fiddlers James Bryant and Blaine Sprouse, Dobroist Gene Wooten and, from “Fragments Of My Imagination,” electric bassist Jimmy D. Brock, banjoist Bela Fleck (“Some day he’ll be a master”) and Sam Bush. Having spent over half his life in and around professional bluegrass has given Butch the outlook and experience of a veteran while still a young man.

“It’s always been some kind of dream for me to play music. It took until just recently to discover how important it is to keep all parts of my act together. I took it as something I could do really well when I was younger and I tried not to get carried away with myself.

“When you get right down to it you’ve always got to look at it like a job. It can’t be any other way. You’ve always got to be physically and mentally in shape to pull it off. I’ve been more conscious here lately about developing a professional attitude about my playing than I’ve ever been. I’m conscious of the thing that I show up on time or ahead of time to do my job, not be temperamental, make do with what is at hand and keep on getting by like any other wandering minstrel does. I’m trying to carry an image about me that I can take pride in and letting people know I’m a friendly sort of fellow instead of someone who’ll just run and hide from them— which I have been known to do before.

“When I started to work the word was that if a musician had to play a square dance that’s when he got so sorry he couldn’t play at all. The reason being he just stood around for three or four hours and he was just bored to tears playing square dance tunes over and over again and he got sloppy. One of the modern gripes and complaints is that people don’t like club work, or working in bars. The thing in bars is that you’re working for a drinking crowd that’s hollerin’ and raisin’ cain and yellin’ for ‘Rocky Top’ and ‘Fox On The Run.’ That’s something that’s got to be done. There are not many people who will resign themselves to the fact that if they’re playing in a bar they’ve got to play that. Hubert Davis is the greatest one I’ve seen at it’. He pulls it off with such class and he does the numbers. You’re building on what you’re doing in a situation like that. You may only have one tune, but you can slip it in three different sets because in most cases your crowd turns over and those who come to see you all the time are going to hear the same songs anyway. I don’t understand this gripe about doing the same song twice in a night. Lester Flatt’s version of ‘Salty Dog Blues’ has been done on every show for twenty-five years. I know bars don’t pay much, but bars build up the chops to where you can get a job where you can get paid more playing concerts or festivals if that’s what you’re looking to.”

As our short vacation drew to a close and we prepared to go our separate ways, Butch’s thoughts again turned to Bill Monroe.

“He’s got such a magnificent dancing rhythm about him. He’ll take you all the way to the depths of the blues if you want to go, but there’s still a sparkle about it. I think he has to control himself some because he lays lead lines down that play more rhythm than what I play behind him. I try to structure my playing around the fact that, when he’s playing, whether it’s back-up or lead, that I should be playing rhythm chunks behind him and not playing rolls that interfere with the staccato effect he might have on the mandolin.

“That man is the ultimate test of being a bluegrass musician. The only way I could ever stand on my feet and say I was a musician is to see the day I could play for Bill Monroe.”