Home > Articles > The Archives > Bryan Sutton Rules

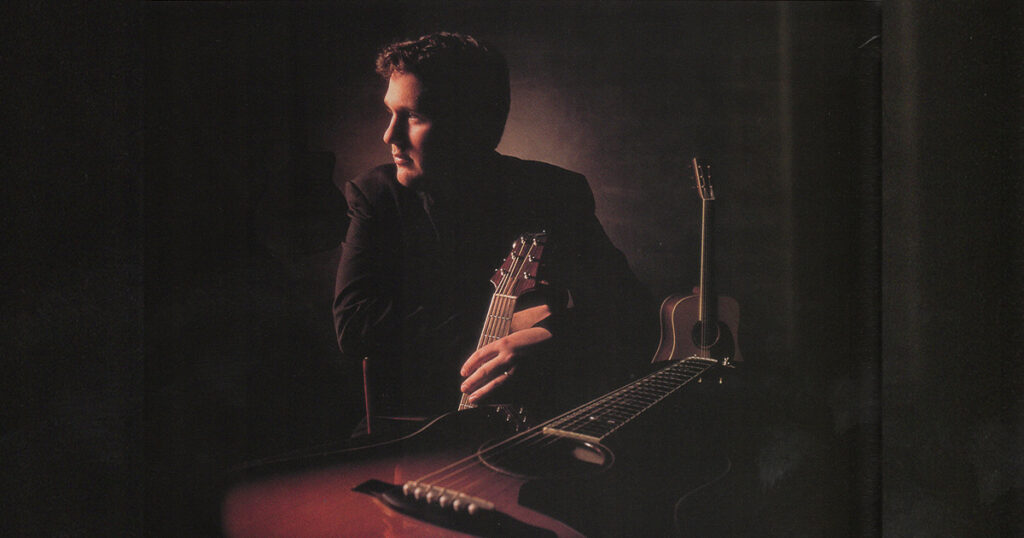

Bryan Sutton Rules

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 2000, Volume 35, Number 2

On a record that became a turning point for bluegrass, a particular Bryan Sutton solo likewise became a turning point for the brilliant young guitarist.

The disc was Ricky Skaggs’ “Bluegrass Rules,” the CD that showed the world at large the immense vitality and attractiveness that still lives at the heart of traditional bluegrass. The tune was “Get Up John,” a cascading mandolin number Bill Monroe recorded in 1953, with Jimmy Martin, Rudy Lyle, and Charlie Cline, and again in 1970, with Bobby Thompson, Kenny Baker, Red Hayes, and Gordon Terry.

Skaggs’ version charged out of the speakers, meeting Monroe’s challenge, recreating that great drive. Then the guitar solo came along and something totally different happened. Sutton’s guitar licks not only flowed dazzlingly hot and fast, but they also boiled over with harmonic and rhythmic ideas that seemed to draw from everyone from Riley Puckett to John Coltrane.

Tim O’Brien, the former Hot Rize star and an equal opportunity collaborator, has been around a while and heard a lot of great music, and made a lot of great music. He heard the “Get Up John” recording at a time when he was trying to fashion something new out of his love for bluegrass, honky-tonk country, folk tunes, Irish music, and new acoustic styles.

“Bryan went into this solo,” O’Brien recalled last fall. “First he played every bluegrass lick, then he went way into the jazz realm with upper partials and all that stuff and those chords. And then he started turning it, playing those chords with bluegrass licks until at the end he was playing it all at once, which to me was wonderful. It changed the world for me. It was one of those moments where I said, ‘Yeah, this is what we need to do, because you’re completing the circle, connecting the dots between all these different things.’ They don’t exist in a vacuum; they’re all interrelated.

“It was great to see Bryan do that in Skaggs’ band, because Skaggs’ band is very traditional. But they gave Bryan the license to do that, which made all the difference.”

Another long-time innovator, Jesse McReynolds, has also tuned in to what Sutton has been up to as a picker. “He’s been the most amazing thing on the guitar I’ve heard lately,” McReynolds noted. “It’s hard to explain. He’s so good and so aggressive; when he hits a note, it comes out. A lot of them when they play so fast, they kind of topple over the notes, but with him it’s all clean.”

Sutton’s ear-grabbing work with Skaggs, who employed him from 1995 to early 1999, brought him to the attention of the bluegrass world just as the style entered yet another mainstream revival. With a new CD, “Ready To Go,” on Sugar Hill, Sutton is getting airplay from Australia to Alabama. The music ranges from flat-out bluegrass to a Dolly Parton vocal showpiece to jazz and delicate fingerpicking.

The disc comes as the latest in a series of heights Sutton has scaled since leaving Skaggs: pitching in for an injured Tony Rice on Bela Fleck’s high-concept “Bluegrass Sessions” tour, picking in Parton’s dream bluegrass band for her well-received “The Grass Is Blue” disc, even showing up on a Dixie Chicks album, and playing sessions for colleagues like Aubrey Haynie, Bobby Hicks, and Jerry Douglas.

But his musical story goes back, almost impossibly far back for a thoroughly contemporary 26-year-old, even one from a highly musical family. First improvised solo in a jam session at age nine or so. First recording session at 17. First paid gig right out of high school. And years of traveling a southeastern circuit of studios, picking from West Virginia to Atlanta to earn a living and to learn the trade. In fact, Sutton is perhaps the most notable example of a New Breed of musicians: startlingly gifted, schooled in all sorts of music, but determined to keep heart and home in bluegrass and its related styles.

Agreeing to meet for lunch in a restaurant not far from Nashville’s Music Row, Sutton was, characteristically, right on time. Now, you wouldn’t necessarily pick the young man out as a picker if he was pumping self-serve right next to you at Mapco. Attractive, broad of face and husky of build, he’s a mainstream X-er to look at, ballcap and all. But there’s nothing of a slacker mentality here: Sutton flat knows what he’s doing, on the guitar and elsewhere. He came to talk about “Ready To Go,” his debut solo recording, as well as the musical path that’s brought him to incipient guitar hero status.

“The bluegrass records that I have done are the fast, get-after-it, hard-driving kinds of things and that is a big part of what I do,” Sutton said. “But I sort of think of it as a total package. I don’t want to be labeled as just a hot, flashy guitar player. It’s sort of a holistic approach; you’ve got to be able to do everything else as well, or try to. So that was my goal here, to include some of that, but also to show everything else that I love to play, slower things, the fingerpicking tunes and the Django swing things.”

Hailing from the rich musical environs of western North Carolina, Sutton got a head start on picking because of his family background.

“My grandfather and his brothers played and then my dad, so I was basically surrounded at all times,” he recalled. “I would wake up in the morning with the Osborne Brothers playing. When I was eight I started playing; I learned from my dad. I had an old Gibson, still have it, a small-bodied L-OO. I started playing it and started with him for a while and kind of progressed with different teachers around Asheville. I started learning some Chet Atkins style playing and then some fiddle tunes with a flat pick.”

In addition to having a background in bluegrass and traditional country, Sutton benefited from learning jazz, rock, and classical techniques. One reason he can play so fast and clean is that he uses sophisticated left-hand fingerings adapted from classical music: hitting notes out of the positions that allow the most efficiency and punch. Along with that training, of course, he got countless hours of informal picking under his belt, much of it in the Asheville picking-party circuit.

“I remember the first tune that I ever improvised on, in a jam session in a circle over there in North Carolina,” Sutton said. “Somebody kind of handed it over to me on the fiddle tune called ‘Cindy.’ I didn’t know it before I played it and I was able to take a solo on it. I was probably nine or ten. I’ll never forget that.

“As I was learning, I had an outlet, basically, in several really good jam sessions there. During the summer there were at least three a week that you could go to and play for hours; it was the best way to learn for me.”

A family band, the Pisgah Pickers, was named for nearby Mount Pisgah, where mom Carol taught and the children attended school. Members included dad Jerry—who shows up as a rhythm guitarist on “Ready To Go”—fiddling sister Leesa and, occasionally, granddad Grover (Chief) Sutton, who’s honored with the CD cut “Chiefs Medley” of fiddle tunes associated with him. “My dad played bass and we had friends of ours on banjo and mandolin,” Sutton said. Since both parents are teachers, it was considered a given that Bryan would attend college, but music had other ideas.

“My experience with college was playing in the university community jazz band and taking some classes with different instructors,” Sutton recalled. “I had opportunities to go and possibilities for some scholarships, and had a plan. But when I was a senior in high school, right before Christmas break, I got a call to do a session, a bluegrass record for Mountain Home records, ‘Gospel Music Salutes Its Mountain Heritage.’ That was my first taste of recording—I was 17—and one of the singers on that record was a lady named Karen Peck, who’s a really really fine vocalist. She was putting together a band and she offered me a position in her band. I kind of went back and forth for a while about whether to pursue college and…what is it? A pedagogical career. I figured after four or five years of college I would still be looking for a gig and here I had one. So I took the gig.”

Sutton stayed with Peck for two and half years, then spent less than a year with the band Mid South, which played contemporary country and gospel music. About this time Sutton also moved to Nashville and started focusing on studio work. The guitarist didn’t move into the big-time, major-label session scene immediately; he’s still moving up the ladder.

“In gospel music there are a lot of small studios and a lot of big studios too, all over the South,” Sutton said. “I would drive myself around from Huntington, W.Va., down to south Georgia and everywhere in between: Atlanta and Greenville, S.C., Charlotte and Knoxville. There are studios that work all the time, so there was a lot of opportunity for me to learn the studio trade.”

Much of the work involved “custom records,” where the group involved—a church group or a family gospel outfit— pays its own way to cut records that they can then market themselves. “They would come in for one day and cut a record,” Sutton said. “You come in for one day and cut a record and then you go somewhere else. It was a good experience. There are wonderful musicians over there that do that work and are still doing it.”

The opportunity to work with Skaggs came along as Sutton, who had left Mid South, was putting in endless miles to fill session commitments. “I was still driving to all those studios in West Virginia and North and South Carolina and East Tennessee,” he said. “I would be gone from Nashville for two weeks at a time just doing sessions. It was good work and I enjoyed it, but I was planning on getting married at the time. I knew that I needed to focus my attention to working in Nashville. I had a little bit going, but nothing to where it needed to be. This gig with Ricky Skaggs opened up through the bass player Mark Fain, who I had done a lot of recording with on the gospel end. He sort of came up the same way. He had been playing with Ricky since April 1995 and I think I joined in July.”

To put this in perspective, Bill Monroe was still alive in 1995 and Ricky Skaggs was still a mainstream country artist doing a primarily electric show. For Sutton, the move did not, initially at least, involve becoming a featured acoustic guitarist in a bluegrass setting.

“I never had any thought or desire that I would be in that position in a major bluegrass band,” Sutton said. “I always considered myself one of the many guys out there that enjoyed bluegrass. I was originally hired to play mandolin and banjo and fiddle and play rhythm guitar and sing. And then the electric player left a year and half after I started and I went to electric guitar and played all the Telecaster stuff. And that’s when Ricky started making his transition to bluegrass.”

It all started to fall together for both Sutton and Skaggs at that point. Skaggs’ change in his country career turned out to be a blessing of sorts; the fierce energy of “Bluegrass Rules” ended up far outselling his recent country albums. For Sutton, the switch to bluegrass meant he had to forge a distinct musical identity out of the wide variety of styles he had explored up until then.

“I hadn’t done a terribly large amount of flatpicking up to that point,” he said. “I’d kind of kept it going, but the confidence that I have with it now as a player, I was nowhere near that. It was quite a job to step in and do it.”

Skaggs, of course, had a deep background in bluegrass: from his child prodigy days to working with Ralph Stanley to Boone Creek and beyond. In the 1980s he hit the top of the country charts, but got sideswiped by a new generation of country “hat acts” offering slicker stuff to radio and fans. His return to bluegrass seemed to unleash pent-up musical fire, with Sutton’s blistering guitar work one of the prime vehicles of the change.

“We were doing the strongest stuff that we could find to do as a band,” he said. “It was a neat feel because Ricky was feeling new to it again and we all were growing with it. It was a really exciting time for me to be in that band and grow as a player, just to work in a bluegrass band like that. It had been in the back of my mind as something that would be neat to do, but I never dreamed that it would be a reality.

“At that time, I was just a utility musician. The session work that I had done required me to play electric guitar and mandolin and Dobro and fiddle, all this stuff. And that’s what I was hired to be with Ricky. My goal was to be the best utility musician I could be: at least very adequate on a lot of different instruments.

I always knew that guitar was my main thing. I never dreamed that I would be in a position where that’s all I could do if I wanted to.”

Leaving Skaggs meant that Sutton could pursue a professional goal of more studio work and a personal one—along with wife Lori, a nurse—of starting a family.

“It was mainly to be home more and I knew the daddy thing would come along soon,” Sutton said. “Living in a town like Nashville, it’s so great to be able to do the session thing—get up in the morning and go to a session and come home at night, not to have to get on a bus.”

Even though he’s concentrating on the-studio, Sutton still finds himself out and around a good bit: playing the heralded “Bluegrass Sessions” tour with Fleck, doing occasional all-instrumental nights at the Station Inn with Aubrey Haynie and others, and making several television appearances with Parton, promoting her all-bluegrass disc. He’s aware of his growing reputation as a guitar hero, but not too worked up about it.

“If people want to think that about me, I guess that’s fine,” he said. “I would just say, ‘Thank you, I appreciate that.’ But I just see myself in a big bunch of a lot of other guys that are kind of doing the same thing I am—Kenny Smith, David Grier, a lot of those guys that I’m a big fan of. I have a lot of my own heroes. I just feel real fortunate to be out front and making records and things. Hopefully some of the things I do people latch onto and that’s pretty cool.”

“Ready To Go” presents a supporting staff of high-level acoustic stars: a core band of fiddler Haynie and bassist Dennis Crouch, resonator guitar heroes Jerry Douglas and Rob Ickes, mandolinists Skaggs and Dave Harvey, and banjo players Ron Block and Mike Snider. The most attention-getting guest is the fabulous Parton, who makes a heart-stopping appearance singing her evocative “Smoky Mountain Memories” with only Sutton’s guitar as accompaniment. The recording is memorable in that singer and picker seem to be breathing together, with Sutton making musical room for Parton’s free-thinking rendering of the song.

“With this particular tune, I went at it like that to see how much I could just follow the things she did,” the guitarist said. “The tempo was all over the place, but that’s the way she sang and that’s kind of the way I wanted it. We had a couple of different cuts where the tempo was more regular and a little faster, kind of the way she did that song originally. But what we ended up with had a lot more feel.”

Elsewhere, “Ready To Go” gets rolling with the snippet of a Lester Flatt G-run that kicks off the mile-a-minute Sutton original called “Decision At Glady Fork.” With Aubrey Haynie matching him dazzling lick for dazzling lick, the tune spins through traditional territory but also takes imaginative new turns with melody and time. The disc continues in bluegrass style, heading right into the 1955 Monroe tune “Brown County Breakdown,” with guitar lead instead of the triple fiddles of the original. This seems typical of Sutton, who’s deeply immersed in the old sounds, but not too reverential to not move forward with this music.

“There’s not tons of guitar solos that you can learn,” Sutton noted. “Like fiddle players and mandolin players and banjo players can learn everything that Chubby Wise and Bill and Earl ever did. There’s rhythm guitar styles you can learn and there’s certain guitar solo styles with George Shuffler and Don Reno and Larry Sparks and those guys. But it’s fun for me, in a solo or lead arena, to go back and learn some of those fiddle and banjo and mandolin licks. It still sounds kind of innovative, because you’ve never heard anybody play them on guitar necessarily.”

On another original instrumental, “Highland Rim.” Sutton shows a gift as a composer, coming up with a memorable, flowing melody with a little rhythmic hook. On this tune, as on others here, there’s a hint of the flowing, evenly inflected, quicksilver style of Sutton’s near North Carolina neighbor Doc Watson.

“Doc and Dan Crary were the first great influences on me,” Sutton said. “Dan Crary has a flatpicking fiddle tunes series on Homespun that I learned a lot from, sitting around the room. Doc Watson was one of the first professional musicians/ guitar players that I ever saw. He doesn’t live too far from Asheville, so I saw him play some different festivals and at Maggie Valley. So he was the first one to really catch my ear as far as what you could do with the flat pick.

“My right hand—it may not as much any more—but I remember at one time it was kind of like Doc’s. It’s kind of like the way Sam Bush plays, using the whole forearm and wrist involved in the playing, whereas with jazz players or Tony Rice it’s more of a wrist thing. I’ve think I’ve got a little bit of both now.”

Another tune recorded by Monroe, “Blue Night,” brings Nashville Bluegrass Band singer Pat Enright to the studio for a moodily eloquent version of the tune. Then Tim White drops in for a bluesy vocal on U2’s pop tune “When Love Comes To Town.” Sutton’s lovely “new acoustic” style instrumentals, “Walk Among The Woods” and “The Good Deed” come along, it’s clear that Sutton has no desire to be limited to one thing, even if it’s something that he does exceedingly well. It’s that versatility that stands him well in his post-Skaggs career as a studio musician.

“Being a session musician in town, there’s no advantage in saying I’ve done this and this and this in bluegrass. In Nashville you are kind of thrown in the pot with a lot of different people, a lot of wonderful musicians, the best in the world. So it’s kind of what’s on the other side of the phone. I still do a lot of custom records and lots of demos for some of the major labels here in town, that’s what I was doing this morning, for Sony and EMI.”

Sutton’s taste for Django Reinhardt shows up in the swing standards “Minor Swing” and “Lady Be Good.” While fully competent jazz, the selections don’t reveal the same distinctiveness of approach and improvisation as Sutton’s country-based playing. The hard-driving tune “Tater Patch” shows off the Sutton touch that keeps budding—and veteran—flatpickers goggling. Everything moves along smoothly and with great musicality even at elevated speeds. There’s more grace than athleticism at work, with clear musical ideas emerging even at the fastest tempos. The familiar old folk song “The Water Is Wide” gets a glistening, romantic treatment, vocally by Sonya and Becky Isaacs and instrumentally from Sutton’s liquidly articulate guitar.

Overall, Sutton’s CD shows his commitment to making an acoustic sound work in a variety of musical settings. “In and around country music, but not of country music, is a good place to be,” he said. “Country is always going to change and it’s just real fickle to me. Being a part of acoustic music is the thing for me, because at some point everybody’s going to go through that. It’s always going to have a place in the American style.”